Night at the Museum

I have always wanted to have sex in a museum. To me museums are ecstasy machines, places to experience rapture, and the real thing is the real thing. So I jumped at what seemed like an unbelievable chance to carry out my fantasy: an opportunity to spend the night with my wife on a rotating queen-size bed fitted out with satin sheets on the sixth ramp of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum. The work, Revolving Hotel Room, is Carsten Höller’s major contribution to “theanyspacewhatever,” a show devoted to the amorphous non-movement known as Relational Aesthetics. Höller’s “room” has no walls, is out in the open on a large round Plexiglas platform, and has a guard posted nearby. If you get up to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, the guard follows you. Intimacy under these conditions seemed dicey, but I had to try. And then, two days before our night in the museum, my wife’s travel plans changed. She was going to be out of town that night. D’oh!

Before I tell you about my personal happy ending, however, some thoughts on the show itself. This cheekily titled outing is devoted to a clique of artists who reengineered art over the past fifteen years or so. They created the most influential stylistic strain to emerge in art since the early seventies. Their impact can be seen in countless exhibitions. Yet “the anyspacewhatever” is less a celebration of these artists than it is an example of well-meaning but incompetent curatorial irresponsibility—further proof, if any is necessary, that while Thomas Krens gallivanted around the world, muddying the Guggenheim brand, he was also ignoring curatorial operations back home in New York.

“Theanyspacewhatever” was organized by the Guggenheim’s Nancy Spector (whose Richard Prince survey last year turned this difficult artist into overpackaged product). Its ten artists, all in their forties, emerged in the early nineties. Relational Aesthetics is a public-oriented mix of performance, social sculpture, architecture, design, theory, theater, and fun and games. These artists view museums as imperfect Edens, playgrounds, battlefields, and sites for seriousness. Over the years they have inserted kitchens, couches, mannequins, and mirrors into institutions. Exhibitions and museums are a medium to experiment with and explore. To them, audience interaction is everything.

Unfortunately, Spector has removed most of the “relational” parts of this art and left us with plain old aesthetics. Wan ones at that, since their work was never that visual. Viewers drift through this show barely stopping; the exhibition is so tame that it’s impossible to imagine anyone’s being challenged to rethink ideas about art exhibitions. Part of the problem can be traced to Spector’s narrow notion about the group, which hasn’t been a group for some time. Part of it is that the Guggenheim simply can’t allow (for example) Rirkrit Tiravanija to set up one of his ad hoc kitchens and dish out curried vegetables for free, allowing the refuse to pile up. Höller wouldn’t be permitted to put hotel beds all over the museum, leaving the Guggenheim open all night to anyone who wanted to sleep over. Mmmmmm.

So we’re left with a show that fizzles instead of sizzles. Tiravanija’s comfy video lounge, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s sonic rain forest, Douglas Gordon’s wall texts, Liam Gillick’s S-shaped benches, Philippe Parreno’s lighted marquee, and Angela Bulloch’s LED night sky are all okay. But the show is lackluster, as if the curator and artists were too busy to do more. Or maybe the artists instinctively fought against being confined by such a thin curatorial idea. And such a surprisingly limited roster. This kind of art sprang up when money left and a new nonvisual, conceptual-sculptural installation art appeared. It was an open, loose moment. Yet somehow, as its stars have ascended to fame and that shagginess has been organized into neat retrospectives, the women, as seems to happen every time, have been shortchanged. Andrea Zittel, Andrea Fraser, Trisha Donnelly, Cosima von Bonin, and Vanessa Beecroft are all missing. Whether or not they belong strictly in the in-group, yet again we’ve got a show that’s 80 percent guys.

That process of canon-building has been destructive in other ways, too. Although this anti-movement began as an excellent palace coup staged by savvy artists, a legion of sheeplike curators has embraced it with a vengeance. For years these annoyingly insular professionals have participated in one another’s panels, schmoozed in hotel lobbies, curated each other’s artists into exhibitions, and written impenetrable texts for one another’s redundant shows. Twenty essays in the “anyspacewhatever” catalogue are by curators! Many of these people have become the weak link in the art-world chain, and they really need to go.

I love much of this art, and I admit that perhaps Spector’s codification was necessary. Maybe paring down the messy reality was the way to make this show happen. But too much was lost on the way. Admirably, hers is the first big exhibition devoted exclusively to the group in an American museum. Given how prim and bland it is, I hope it will be the last.

Which brings me back to my no-sex-in-the-museum evening. Höller’s hotel room—booked solid at $259 to $799 per night—is the highlight of the show, and is too good to miss. After my wife canceled, I went anyway, alone. Arriving was fun: I was greeted at the door, got signed in, and was shown to my room. As the guard, Joseph, watched, I hung up my coat, unpacked, and set up my bedside table. After showering in what looked like a swanky executive bathroom upstairs, I changed into pajamas and a robe, and began roaming the museum (at one point sneaking into a classy office to put my feet up on the desk and pretend to call Bilbao). I lay down on floors and stood in empty galleries. At first, it was all a delight. Then it got weird. I felt very alone, as if I were in one of those last-person-on-Earth films. Paranoia set in, as the museum turned into a modernist minimum-security prison, a panopticon, and instead of feeling in control via looking at art, I felt like I was the thing being looked at. OMG, were there cameras trained on me? Probably.

So I went to bed. As I lay there, I heard strange sounds—fans whirring, echoes reverberating. I couldn’t sleep, despite earplugs and an eye mask. I began counting all the shows I’d seen here over the decades. Eventually, that did the trick, and around 2:30 a.m., I drifted off. The next thing I knew, Joseph was tapping his walkie-talkie on the bed, saying “Get up.” I had slept the sleep of the dead. I took off the mask and saw that the lights were on and workers were moving about. It was 7:30. As breakfast (tea, croissants, pain au chocolat) was wheeled toward me, I noticed that I felt refreshed—that the Guggenheim, where I’d been a thousand times, looked utterly new to me. I was in love with the place. The museum had become a cradle of sorts; the environment seemed whole and enveloping. I had the strange feeling of having merged with the structure, like we really had slept together.

The next week, when I returned to the show by day, I noticed that when I passed by the bed where I spent that night, I was filled with tender feelings. It was like walking in a city and looking up at a window in a building and remembering a long-ago night when you’d had sex there. Weirdly, however, I was also filled with something like jealousy. I felt like “my museum” was sleeping with everyone else. I found myself wondering why the Guggenheim hadn’t called the next day.

theanyspacewhatever

Guggenheim Museum. Through January 6.

E-mail: jerry_saltz@newyorkmag.com.

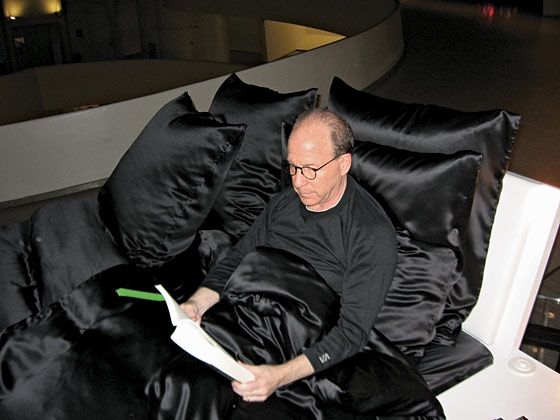

Arriving for my night at the museum.

Photographs courtesy of the Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum

There’s a guard; you can’t steal the hangers.

The shower’s pretty good, too.

And who doesn’t want to be comfy “

” when visiting the Catherine Opie show?

Höller’s Revolving Hotel Room has satin sheets.

I brought Anna Karenina to read. (I promise I wasn’t showing off.)