Analysis

‘After a Long Sleep, It Woke Up’: What Is Driving the Market Frenzy Around Late German Artist Günther Förg

The German artist's prices are peaking.

Around five years ago, a new plutocracy pouring money into art fueled the rise of a new generation of abstract painters who became known as the “Zombie Formalists.” Before too long, however, the number of largely anodyne, process-driven paintings coming out of their studios—and the price points for those rapidly multiplying works—grew out of control, and the market for them imploded.

At the same time, demand for decorative, abstract paintings never quite evaporated. And in the years since the Zombie Formalist boom ended, collectors have begun to look further back in history to seek security in the work of a more established generation of artists who explored the form.

This shift is perhaps best exemplified by the renewed interest in the late German painter, sculptor, graphic designer, and photographer Günther Förg, whose major retrospective “A Fragile Beauty,” organized with Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, opened last week at the Dallas Museum of Art (on view through January 27).

What’s Old Is New Again

Although Förg worked in a variety of media, he is perhaps best known for his abstract paintings that toyed and tinkered with the notion of modernism in a postmodern age. “The significance of Förg lies in his relation to modernism,” says the curator Hripsimé Visser, who organized the recent exhibition at the Stedelijk. “He is pointing to the underlying ideologies and premises of modernism in a way that has already been discussed and questioned thoroughly for some time now.”

Installation view. Günther Förg “A Fragile Beauty” (2018) at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij, courtesy of the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

From his early monochrome works in the 1970s (during which time he only used gray and black) to his colorful dot works and photographs of Bauhaus buildings, the artist was a relentless experimenter. He became best known for using metal—particularly lead—as his surface of choice for paintings.

Some bristle at any attempt to draw a line between Förg’s work and that of the so-called “Zombie Formalists.” To be sure, the former has a longer history and follows in a more robust intellectual tradition than the latter. (TheNew York Times once called Förg’s paintings “obliquely grandiose.”)

The curator and critic Mathieu Poirrier, for example, dismissed the demise of the Zombie Formalists as “a correction of judgement and thus market value.” By contrast, he sees the generation of older artists that came before them—including Förg—as “major inventors of modern art that were not considered because almost everyone forgot how relevant they are.” He says Förg, in particular, “has been underrated for a few decades.”

Now, however, that is changing. Collectors have grown weary of abstract painting that constantly references Abstract Expressionism, which Poirrier says has “become too obvious.” Instead, buyers are interested in reassessing the generation of painters who came two generations after Ab Ex and one generation after Minimalism—artists who have sought to absorb but reinvent their predecessors’ traditions.

Günther Förg at the Dallas Museum of Art (installation view). Photo: courtesy of the DMA.

Paul de Froment, the director of Förg’s former New York gallery Almine Rech, notes that the German figure “placed himself at the junction of a lot of very interesting artists that are also rising in the market—although they are at another level—like Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, or even [Donald] Judd, with his interest in architecture, hard-edge painting, angles, and grids.” In a way, he argued, “Förg is more the contemporary heir of those artists. His work is the continuation of those people.”

The Numbers

Since Förg died of cancer in 2013 at the age of 61, prices for his work have risen steadily. In 2016, his current auction record was set at Phillips when his six-part painting Untitled (1994) sold for $815,000 in New York. His top 15 auction prices have all been set in the past five years.

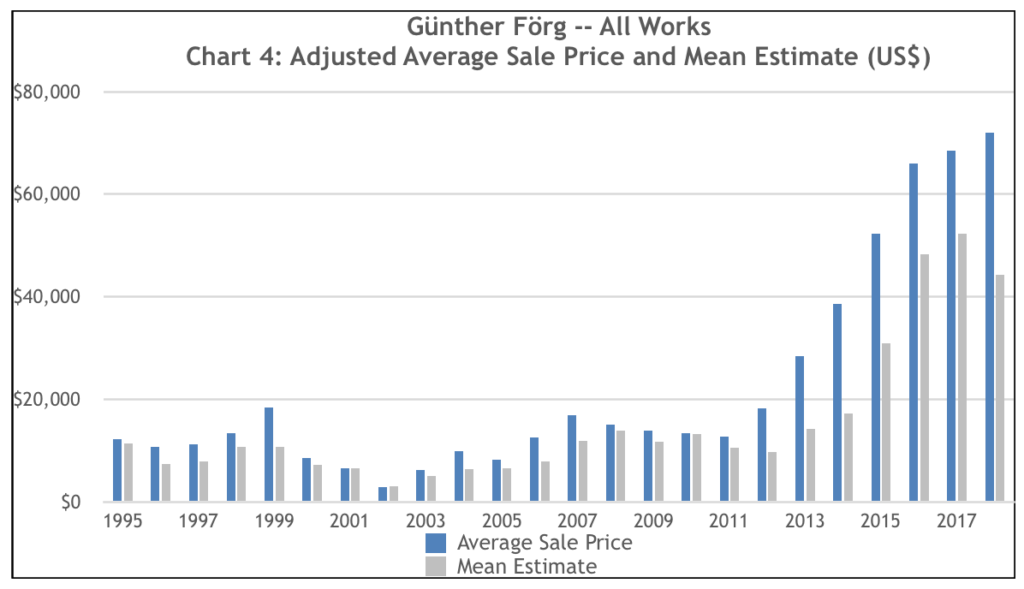

And now, according to the artnet Price Database, his auction prices have reached a peak. The year is not yet over and Förg’s average sale price has already hit an all-time high of $72,052. Meanwhile, in the first six months of 2018, the artist’s total sales at auction were up 31 percent over the equivalent period in 2017. His sell-through rate also rose from 69 percent in the first six months of last year to 86 percent in the first six months of this year, while the number of lots sold rose by 62 percent.

By a slightly less official measure, we can also see that interest in Förg has grown considerably. Over the past 10 years, he had the sixth largest increase in searches on the artnet Price Database of any artist, meaning that his market is being tracked much more closely than it was a decade ago. (The number of searches rose from 783 in 2008 to 2,525 in 2018.)

2018 © Artnet Worldwide Corporation

2018 © Artnet Worldwide Corporation

Rebekah Bowling, a specialist at Phillips, says that the auction house’s 2016 record prompted a surge of inquiries, particularly around spring 2017, from collectors hoping to buy Förg’s work privately. “Geometric abstraction is pretty enduring,” she explained. “The works are very easy to live with and timeless… but they also look distinctively Förg because of his materials and process.”

Over the past year, she says, interest has climbed even higher thanks to the current traveling retrospective and the news, announced in June, that Hauser & Wirth would represent the artist’s estate worldwide. The mega-gallery, which is planning its first exhibition devoted to the artist in the US in 2019, plans to commission new research about Förg and support the publication of his catalogue raisonné.

In a statement at the time, the artist’s widow and longtime assistant said that since the artist’s death, “we have been focused on establishing the estate and now require a different kind of gallery representation.”

Speaking to artnet News, Hauser & Wirth partner and vice president Marc Payot described Förg as “a very important artist who is undervalued in comparison to other artists and painters.” He added that the gallery plans to take advantage of its global reach by contextualizing his work around the world, including in Asia and the US, where he is lesser known than in Europe.

The gallery will present a large survey exhibition across two floors of its 22nd Street space in New York in the new year. Meanwhile, it will stage a “more didactic” exhibition in Hong Kong, taking a similar promotional strategy to the one it adopted for the Phillip Guston estate in the region. “The potential in Asia for Förg and the understanding for his work there is really big,” Payot said.

The Most Sought-After Works

Although Förg worked extensively in photography and sculpture (even abandoning painting entirely for a spell in the early ’80s), his paintings on lead remain the most commercially successful part of his oeuvre. “I think everybody wants a little of that lead visible, be it a Barnett Newman-like stripe or a little bit of brushiness where you can see the lead coming though,” Bowling said. “People want it to look like a Förg,” she added, “and those are the ones that look like Förg in people’s minds.”

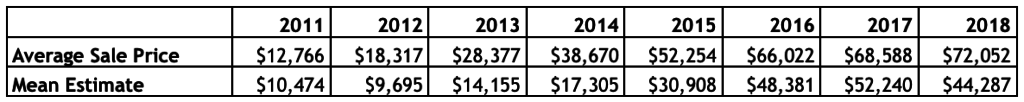

Günther Förg’s $815,000 record-setting work Untitled (1994). Photo: courtesy of Phillips.

A look at artnet’s Price Database supports Bowling’s claim. His monochromatic works and colorful multi-paneled works on lead command the highest prices. Among his 10 best-selling works at auction, six are monochromatic paintings, and four are colorful multi-paneled paintings. At Christie’s London in early October, his meditative gray and orange work on lead from 1999 sold during a day sale for £452,750 ($593,303), tripling its £150,000 high estimate and becoming his tenth-highest price at auction.

There is strength in the middle and lower segments of his market as well, particularly for his acrylic on lead works. All seven works offered at the fall auctions in London (including the gray and orange work) met or outperformed their estimates, which ranged from £30,000 to £300,000. Similarly buoyant performances took place earlier this year: In June, a four-panel pastel and aluminum painting sold at Christie’s Paris for more than $100,059, outperforming its high estimate by 183 percent.

In New York next month, Sotheby’s will offer the artist’s Untitled (1990) (est. $250,000–350,000) in its contemporary day sale, while Phillips has the artist’s diptych Farben (2000) (est. $20,000–30,000) in its day sale and a pastel-on-paper in its online-only “Unbound” auction.

Günther Förg, Untitled (1990). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

All Boats Rise With a Rising Tide

Some say the mercurial rise in Förg’s market has less to do with the artist himself and more to do with the market at large, which has expanded and developed an infatuation with overlooked estates over the past five years.

“The market loves estates of good artists with a ton of available material,” art advisor Wendy Cromwell said. “The period between 2013 and the present has been one of unprecedented growth in the art market. There is so much demand and so little inventory. That is why his work became so widely known all of a sudden—after a long sleep, it woke up.”

Even though European audiences may be familiar with the German post-modernist’s work, the advisor contends that he remains underexposed in America—not to mention Asia and further afield. But with the Dallas show underway and Hauser & Wirth’s shows in the works for 2019, a proper contextualization of his broad oeuvre could take him to the next level in the international market.

“A well-curated [museum] show, when it’s good, typically does stimulate growth in the market and I do anticipate that,” Cromwell said.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment