Art

9 of the World’s Weirdest Museums

In this day and age, there’s no shortage of specialized museums. From the weird to the whimsical, and including everything from funerary paraphernalia and ancient relics to scientific objects and erotica (with a fair bit of fakery thrown in), you can find a collection dedicated to just about any curiosity imaginable. We’ve rounded up nine of the world’s most offbeat institutions that offer a unique, if often wholly unexpected, visitor experience.

Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature

Paris, France

Salon de Compagnie. © Sophie Lloyd. Courtesy of the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature.

One might think that a museum devoted to hunting and nature housed in an 18th-century aristocratic residence on Paris’s Right Bank would be stuffy and rather ethically contentious. In the case of the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, however, you’d be wrong. Yes, it’s filled with a requisite, perhaps even excessive, amount of taxidermy—including a sleeping fox perched on an ornately upholstered chair and a giant animatronic bear that periodically emits a motion-activated roar—and enough ornate crossbows and polished guns to arm a small, posh militia. But the museum takes as its mission the promulgation of respectful hunting practices and ecological preservation.

The history and culture of European hunting is revealed through Renaissance-era artifacts and objects, Flemish master paintings by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, and contemporary works and installations by the likes of Jeff Koons, Jan Fabre, and Mark Dion. There’s no want for whimsy, either, given the entire room dedicated to unicorns and their undeniable existence as proven by 17th-century scholars.

Museum of World Funeral Culture

Novosibirsk, Siberia, Russia

There is perhaps no better place to contemplate one’s mortality than the furthest reaches of Russia, where a deathly cold breeze blows across Siberia nearly year-round. In the region’s unofficial capital of Novosibirsk, you’ll also find one of the only museums in the world devoted to the exploration of global funerary practices, the Museum of World Funeral Culture.

Its collection boasts thousands of paintings, drawings, photographs, engravings, and objects exploring themes of death and, of course, dead people. Exhibitions include a stylish showcase of hundreds of mourning dresses dating from as far back as the 14th century and the architecture of 19th-century cemeteries, crosses, and tombstones. But the museum is just one part of owner Sergei Yakushin’s greater Disneyland of death, which also comprises a factory that produces “mourning industry” wares, displays of urns, caskets, model hearses, a memorial park and research library, and a crematorium he continues to own and operate. The morbidly delightful compound also plays host to Necropolis — Tanexpo, an annual fair of ceremonial rites and services.

The Museum of Jurassic Technology

Los Angeles, California

Rooftop Garden and Colonnade at the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Courtesy of MJT.

If you’re confused by the name of this museum, you are not alone; few know exactly what Jurassic technology is, if it in fact refers to anything at all. The elusively named institution began as a traveling museum in 1984, founded by artist and designer David Hildebrand Wilson and his wife, Diana, before taking root in an unassuming building in Culver City, L.A., in 1988. It functions less as a place to showcase their idiosyncratic collection of historical, ethnographic, and art objects, and more as an experimental space to explore the human practice of collecting.

It’s unclear how often its exhibitions change, if ever, but long-standing visitor favorites include “Garden of Eden on Wheels: Selected Collections from Los Angeles Area Mobile Home and Trailer Parks”—a display of mobile home dioramas, snapshots, and objects that explore the history of movable homes—and a series of stylish portraits of dogs that participated in the Soviet Space Program between 1959 and 1961.

If you can’t make it to L.A. to experience its uniqueness in person, you can read about it in the writer Lawrence Weschler’s book devoted to the peculiar and fascinating collection, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder: Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology (1995).

Museum of Old and New Art

Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

Tasmania is known to many as the home of Taz from the Looney Tunes cartoons, but this island state off the southern tip of Australia is home to another character who marches to the beat of his own loony tune—David Walsh, professional gambler, eccentric multimillionaire, and founder of the equally unconventional Museum of Old and New Art.

In his three-floor subterranean museum, which opened in 2011, you can find objects ranging from Ancient Egyptian mummies to contemporary French artist Christian Boltanski’s 2010 video piece The Life of C.B., a 24-hour live feed of his suburban Paris studio streamed for a monthly subscription fee that is paid by Walsh. There’s no real rhyme or reason to this collection except for the whims and fancies of its founder. Interests that evidently include defecation if Stephen J Shanabrook’s suicide-bomber entrails cast in chocolate and Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional (2010), also referred to as the “shit machine,” are any indication.

Miho Museum

Shiga Prefecture, Japan

Courtesy of MIHO.

Surreptitiously nestled in a densely forested nature preserve just southeast of Kyoto (and currently closed through March 9, 2018), the Miho Museum is a work of edificial genius by I.M. Pei, the same architect who designed the Louvre’s iconic glass pyramid. Most of the Miho building sits below ground, but the rest of its streamlined glass, steel, and limestone looks like it’s been wrought directly from the mountaintop on which it sits.

This unexpected architectural gem houses a collection of Western and Asian antiquities and artworks such as Roman wall paintings from Pompeii, as well as one of the largest 2nd-century Gandhara standing buddha statues known to exist. Most of the collection was acquired within just six years by Mihoko Koyama, the heiress to the Japanese textile company, Toyobo, and founder of her own religion known as Shinji Shūmeikai, the central tenet of which is spiritual healing through art.

“We don’t necessarily intend to show objects art-historically or even stylistically,” says Miho curator Inagaki Hajime, who explained that the aim of the collection is to posit the works in the collection as part of a psychohistory of humankind. “In this way, we have a difficult obligation or responsibility to extract each object’s spirituality.” Another central pillar of Koyama’s faith? The restoration of nature’s balance through the construction of beautiful buildings in far-flung locations.

Museo della Frutta

Turin, Italy

The golden age of fake-fruit modeling ended with the passing, in 1889, of Francesco Garnier Valletti, whose collection of hundreds of artificial apples, pears, peaches, plums, and grapes make up the collection of Turin’s Museum of Fruit. In his time, Garnier Valletti was considered a virtuoso in the field of pomological modeling—the practice of which had a rich history in Italy, beginning in Tuscany in the 18th century.

He was known for his innovative use of wax and ash to create fruits that were appropriately weighted as if ripe with juice and slightly tender to the touch. He also employed a crushed-wool technique to emulate the fuzz on stone fruits like peaches and apricots. The museum, however, is more than just an evergreen orchard—the painstakingly modeled and taxonomically identified collection of fake fruit offers a comprehensive history of agricultural development in Italy and the effects of human interference into biodiversity.

Spritmuseum

Stockholm, Sweden

Photo by Jonas Lindström. Courtesy of Spiritmuseum.

Sweden has a complicated relationship to drinking due to its monopolistic state-run Systembolaget chain of liquor stores—the country’s only legal retail purveyors of spirits with over 3.5 percent alcohol content—which perhaps makes it an unlikely place to find a museum devoted to booze. But at Stockholm’s Spritmuseum, drinking reaches a level of near-fetishization.

Here you can learn about the history, consumption and distribution norms, food pairings, and traditional songs associated with many a fine tipple. Step into the “hangover room” to experience the other side of a debaucherous night, where harsh lights, loud music, and off-kilter seating make nauseating additions to a first-person film that follows a guy on a bender. The museum also plays host to the Absolut Art Collection, comprised of the 850 artworks that the Swedish vodka brand commissioned of its iconic bottle over the years, including those by artists George Rodrigue and David Shrigley.

(Exactly where this million-dollar marketing idea came from is the subject of dispute, according to Mia Sundberg, curator of the Absolut Art Collection, but most believe it started with Andy Warhol, who presented the company with a painted bottle in the spring of 1986 that ultimately ran as an ad inInterview magazine.)

World Erotic Art Museum

Miami Beach, Florida

Naomi Wilzig was posthumously quoted in her 2015 Miami Heraldobituary as having told the paper in 2002, “I’m a crusader to get John Q. Public to accept that erotic art is out there. We accept violence, but we go crazy over the idea of a nude body.” The collector, who reportedly grew up in a conservative Jewish family and whose banker husband never much cared for her taste in art, successfully launched this crusade with her World Erotic Art Museum in 2005.

It’s comprised of roughly 4,000 artworks that evoke the pleasure and pain of love by creatives ranging from little-known folk artists to big names like Rembrandt, Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Bunny Yeager. The museum’s programming foregrounds sex-positive inclusivity, and its current exhibition, “Kinsey Institute: Untold Stories,” gives voice to perspectives on sex that have largely been excluded from mainstream dialogue.

Additionally, a new gallery focuses on the collection and practice of Magnus Hirschfeld, a German sex researcher whose art and library faced Nazi scrutiny (and destruction) in 1933.

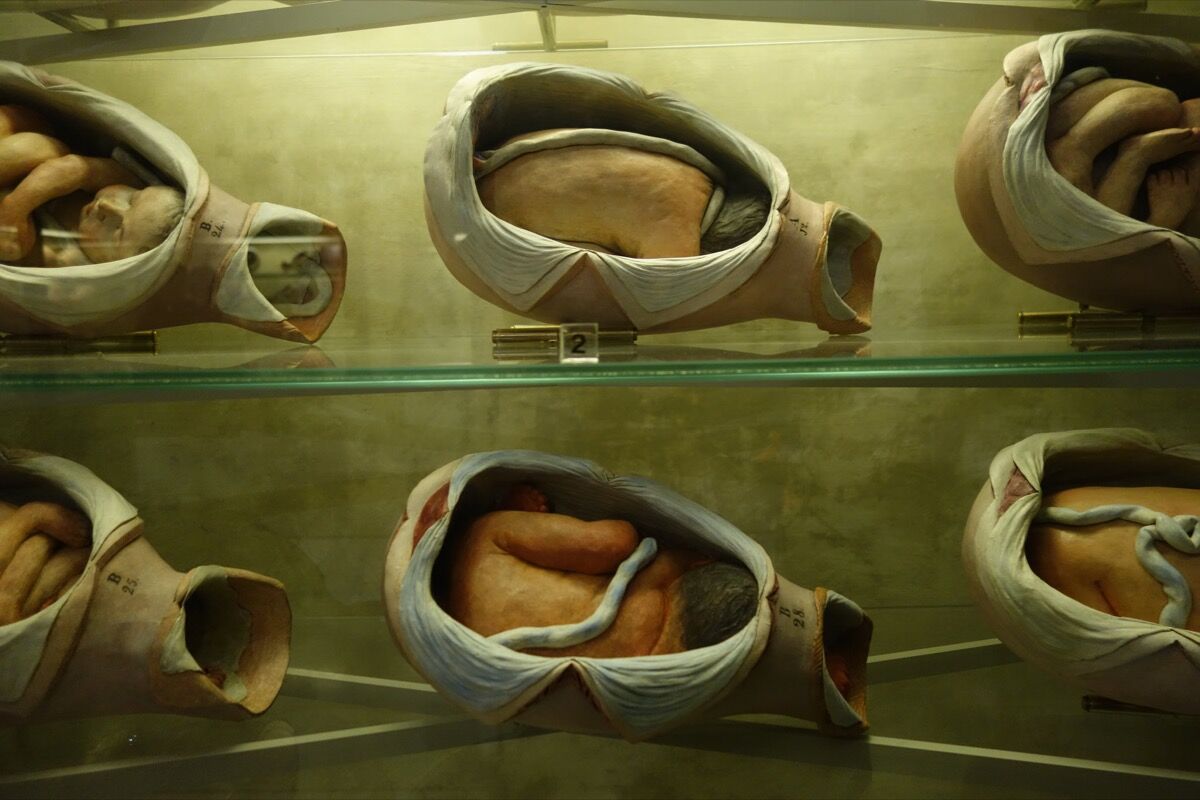

Musei di Palazzo Poggi, Obstetrical Museum

Bologna, Italy

Wax wombs at the Museo di Palazzo Poggi Anatomy & Obstetrics. Photo by Geoffrey Rockwell, via Flickr.

One of several curious collections found in the opulent 16th-century Poggi Palace (now part of the University of Bologna), the museum’s selection of anatomical models and surgical instruments has some of the finest waxworks and rarest medical tools in the world. It was amassed at the personal expense of an 18th-century Bolognese doctor, Giovanni Antonio Galli, with the intention of educating midwives in childbirth since, as women, they were excluded from medical schools and relied largely on anecdotal information about birthing—as well as a fair bit of trial and error. Students could practice delivering fetuses from a life-sized uterus, a highlight of the collection.

The museum is also home to a wax self-portrait by 18th-century anatomical sculptor and professor Anna Morandi Manzolini and Venerina (c. 1782), a reclining Venus figure by sculptor Clemente Susini, complete with removable organs.

Margaret Carrigan

No comments:

Post a Comment