vira-te || turn around

Prado exhibition takes a rear view look behind some famous paintings

Reversos (On the Reverse) explores the backs and frames of artworks to reveal their stories, secrets and travels

The Prado has decided to turn its back on its visitors. Those attending the Madrid museum’s latest exhibition are greeted not by the full splendour of its most famous work, Velázquez’s Las Meninas, but by an austere and lifesize recreation of the reverse of the painting.

Elsewhere, among the self-portraits of Goya, Rembrandt and Van Gogh, there is a seemingly devout nun baring her bottom, a painting whose frame bears witness to its seizure by the Nazis, and five battered wooden beams from the original stretcher of Picasso’s Guernica.

The idea of the new show, called Reversos (On the Reverse), is to take the viewer beyond the surface of an artistic image and to encourage them to see the physical painting, its back and its frame as objects that conceal – but can also reveal – secrets, stories and meanings.

According to the Prado’s director, Miguel Falomir, the exhibition’s genesis lies in Las Meninas, in which Velázquez stares out at visitors from behind the huge canvas he is working on.

“The exhibition aims to remind us of something that I think Velázquez would also want us to consider if he were here, which is that art – and painting in particular – isn’t just about the image itself,” he said.

“Works of art are three-dimensional; when we focus solely on the image, which is a reproduction of a given moment frozen in time, we get some information, but we miss a lot when it comes to everything that the work means as an object. I like to say that when you see a piece and its back and its frame, it’s like standing before an archaeological discovery in which each layer has its own story to tell us.”

To that end, the show’s curator, Miguel Ángel Blanco, has gathered together 105 pieces from the Prado and from 29 international museums and collections, and installed them in two rooms that have been painted black to create a “cavern-like atmosphere” of mystery and revelation.

Some of the works can be seen from both sides and some have their painted side to the wall to better show off the messages, stamps and sketches that decorate their backs and which have gone unseen for so long.

Falomir likens the exhibition to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland – “it’s like entering another dimension that’s not there, a dimension that’s hidden but which is hugely important and which is as much a part of the work as the front”.

Divided into 10 sections, Reversos offers visitors the sights they have traditionally been denied.

“The great majority of paintings have always been hung from walls in museums where there’s no chance for people to spy out what’s behind the image and where you’re forbidden to get close to the objects – the frames are usually fixed to the walls and rigged with security,” said Blanco.

“And sometimes the backs of the pictures are sealed up with plastic to stop the dust getting in. Accessing the backs of the pictures is a privilege only afforded to restorers, conservators, authorised researchers, transport companies and framers – and obviously artists.”

Blanco said that flipping the paintings allows the spectator to enjoy and understand them as objects rather than as mere images. Take the well-travelled and exhausted-looking wooden struts that once secured Guernica, he said, or Salomon Koninck’s painting of a philosopher, whose reverse contains a press cutting of an obituary and other signs that show it was once part of a collection that was stolen from its Jewish owner by the Nazis.

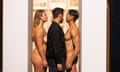

But perhaps the most eye-catching exhibit, Blanco added, was Martin van Meytens’ Kneeling Nun, painted around 1731. Its front shows a devout nun at prayer, watched over by an older nun. Its reverse, however, shows the nun with her habit hitched up over her naked bottom.

“It’s an excellent example of a pornographic image half-hidden on the reverse that belonged to the Swedish ambassador to Paris, who kept it hidden and only showed it to special guests,” he said.

Blanco, who is also an artist, has three pieces in the exhibition. To make the trio of box-books, he used the “cloud of dust” that was left behind after restorers at the Prado took a huge 16th-century copy of Raphael’s Transfiguration off the wall for the first time in decades.

Embracing and transforming the dust is very much in keeping with the passions of a man whose desire to look beyond the surface has inspired the exhibition – even if it also appears to have made him something of a nightmare for museum security.

“I should never have started looking behind pictures,” Blanco confessed. “Now, whenever I’m in a museum or at an exhibition, I creep along the walls gazing at the frames and into all those dark, shady and secret places.”

On the Reverse is at the Prado in Madrid until 3 March 2024

… there is a good reason why people choose not to support the Guardian.

Not everyone can afford to pay for the news right now. That’s why we choose to keep our journalism open for everyone to read. If this is you, please continue to read for free.

But if you can, then here are three good reasons to make the choice to support us today from Portugal.

1. Our quality, investigative journalism is a scrutinising force at a time when the rich and powerful are getting away with more and more.

2. We are independent and have no billionaire owner controlling what we do, so your money directly powers our reporting.

3. It doesn’t cost much, and takes less time than it took to read this message.

Choose to power the Guardian’s journalism for years to come, whether with a small sum or a larger one. If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just €2. It takes less than a minute to set up, and you can rest assured that you’re making a big impact every single month in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment