t

The Precarious, Glamorous Lives of Independent Curators

Asked what advice she has for her younger peers, independent curator Jacqueline Mabey laughed. “I don’t know if you should get advice from me,” she said. “I’m in my mid-thirties, with green hair and no savings!” Mabey—who is perhaps most widely known for her work with Art+Feminism, a project meant to tackle gender imbalances in Wikipedia’s arts coverage—isn’t alone in evincing a cheerful gallows humor about the state of her field.

Museums and galleries rely on independent curators to bring fresh perspectives and new voices into their programming, often pairing them with staff curators when organizing exhibitions. But the creativity and flexibility independent curators bring often comes at the price of much financial stability, pay, or benefits for the curators themselves.

The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that there were 12,400 full-time curators working in the U.S. as of 2016 earning an average of around $59,000 annually. The number of curatorial jobs, which counts all curatorial positions, not just those involved with the arts, is projected to grow 14% by 2026, to an estimated 14,100. The total number of people working as independent curators is difficult to estimate since many take on other roles—as art advisors, writers, and teachers, for example—alongside their curatorial work.

The job itself varies widely: from overseeing group shows in alternative spaces to curating special sections of major art fairs or acting as more informal “curatorial correspondents” for major biennials and the like. Candice Hopkins, who later went on to more prestigious gigs working with the likes of Documenta, recalled her early days at an artist-run space in Vancouver, where her duties included painting the gallery, tweaking the lighting, and fixing the bathroom when it broke.

Portrait of Jacqueline Mabey by Michael Mandiberg.

“The labor varies depending on the size of the organization you’re working with,” Mabey said. “I’ve curated in artist-run spaces where it was me personally deadlifting 20-year-old televisions into place…and thinking about the glamorous life of the curator while doing it.”

Payment, likewise, is all over the map, depending on whether one is doing a favor for friends, or generating content for a global brand. “Like most aspects of the art world, curators’ fees are not regulated, and there are no set norms,” said Renaud Proch, Executive Director of Independent Curators International (ICI), an organization launched in 1975 that produces exhibitions and supports those working in the field. “Things change depending on context, city, resources available, and the curator’s experience. If it’s a collaboration with a commercial gallery, some curators may prefer a flat rate, while others prefer a cut from sales. It’s really murky and case-by-case.”

Those working in the industry, many of whom wished to remain anonymous when citing specific figures, shared a range of curatorial fees within the commercial gallery sector: A $2,000 flat fee plus 10% commission for curating a show at a “new gallery in its infancy,” or $2,000 plus a 20% commission (once total sales reached $10,000) for a “mid-level Lower East Side gallery.” Another gallery, founded in the mid-1990s and with outposts in both New York and California, pays roughly $2,500 to outside curators (with the expectation that they’ll assist with an event like a walk-through, talk, or V.I.P. dinner).

“I’ve been personally deadlifting 20-year old televisions into place, and thinking about the glamorous life of the curator while doing it.”

An established New York gallery paid around $7,500, plus around $4,000 in additional travel expenses, for an independent curator (who also contributed a catalog essay as part of that fee), though the source here noted that this, for various reasons, was a bit higher than the norm. The same space paid around $5,000 to a curator in charge of a summer group show.

Mexico City-based independent curator Chris Sharp, who also co-runs the space Lulu, said that his asking rate for such an undertaking in a commercial gallery space is a minimum $5,000 plus accommodations and airfare. When curating a show in an institutional setting, Sharp’s ask is 10% of the organization’s total budget for the exhibition, which he called “more or less standard in the business.”

For a three-month project in 2017 with the nonprofit ifa-Galerie Berlin, Puerto Rico-based curator Marina Reyes Franco was given airfare and lodging, a monthly subway pass, and a €3,000 stipend.

James Burns, who has worked with museums for around three decades and now runs an independent curatorial and advisory firm called Cypress & Sage Advising, operates in a variety of ways—from working with institutions to assisting private collectors and living artists, while simultaneously teaching in an adjunct capacity, and writing. He prefers, when possible, to accept commissions with an hourly rate, rather than a project fee—but admits that many clients aren’t comfortable with that arrangement. “I did a survey of freelancers when I started my business full-time,” he said, “and $100/hour seemed to be the general going rate, though higher in certain major metropolitan areas.”

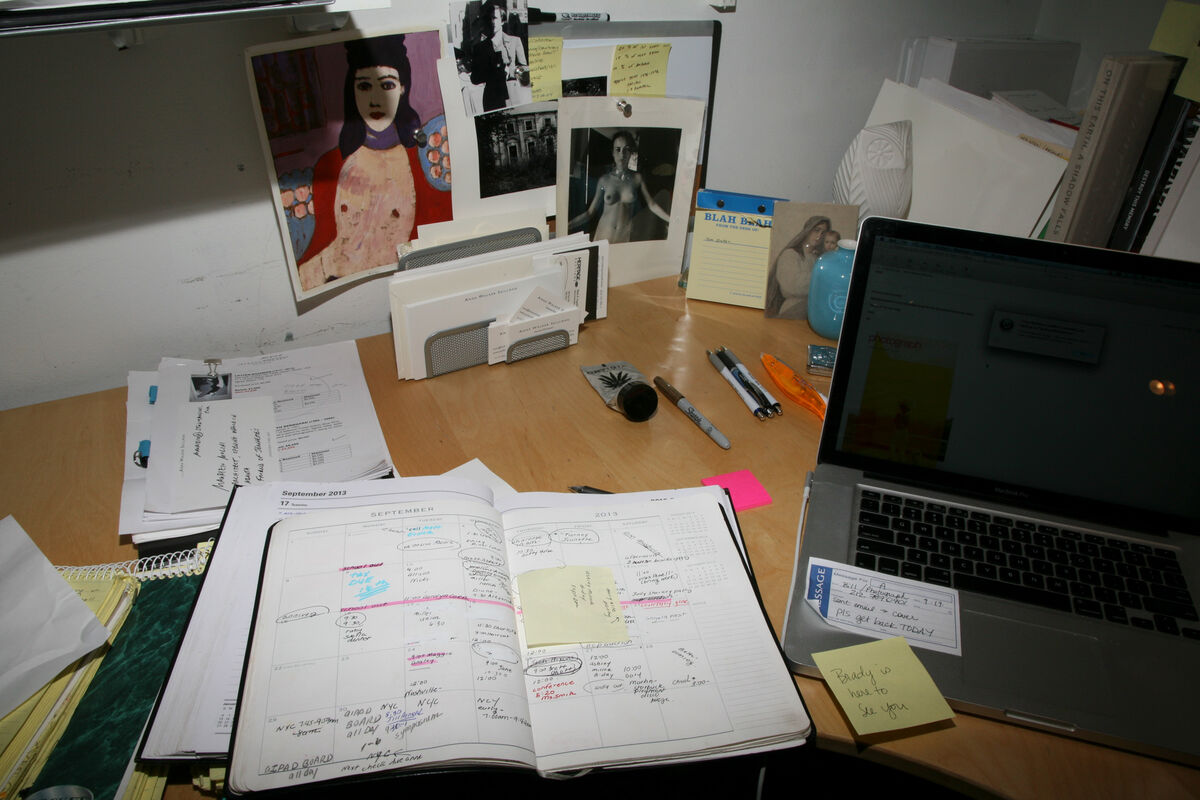

E. Brady Robinson, Anna Walker Skillman from Jackson Fine Art, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Occasionally, research grants or awards—like those promoted or supported by ICI, or by the Canada Council for the Arts—can help curators stay afloat. Some are fairly generous, like ICI and the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros’s Travel Award for Central America and the Caribbean, which can come with up to $10,000 of funding.

The sums might all sound profitable enough at face value, but dollar amounts don’t always take into consideration unpaid time independent curators spend preparing for exhibitions. A European-based curator I spoke with cited remuneration between $10,000 and $20,000 each for two large-scale exhibitions set to open in 2018 and 2019, respectively. The planning stages for those shows, she said, stretched across two years. The aforementioned $7,500 fee paid to a curator by a New York gallery was also for a project that unfolded over two years. And obviously, an independent curator is not going to be overseeing 10 shows at mid-level commercial galleries each year—roughly the amount of work required to pull in a pre-tax income of $50,000 based on average rates, a modest salary by the standards of most art capitals.

A cynic might argue that depending on contractual labor is a financial decision for museums and other institutions, allowing costs to be cut—the sort of gig economy sea change that has affected everything from academia to the taxi industry. But the broader benefits are more nuanced. One upside for museums is that outsiders can “usefully question the existing parameters or limits of that institution,” said Johanna Burton, Director and Curator of Education and Public Engagement at the New Museum in New York.

Burns concurred. “[Independent curators] can ask the questions that peers within the institution might avoid asking; they ask the questions that everyone else is thinking.”

“That said,” Burton noted, “I’m mindful that in some situations, independent practitioners are not well paid, with visibility and ‘opportunity’—often equated with cultural capital—seen as equally compensatory.” In other words, the age-old story of exposure standing in for cash, a scenario familiar as well to freelance writers who might forego payment in order to build a flashy portfolio.

Burns also posited an interesting trend developing that separates full-time, institutionally-based curators from their independent peers. “Museum curators find themselves more and more pressed to become generalists,” he said. “The museum can’t afford to have that many specialists on staff, full-time. While it’s unfortunate that they can’t afford it, it’s good that there are independent curatorial professionals out there that do have the kind of speciality and expertise that museums can turn to.”

“Contemporary art is a social industry. Who you know and whom you have access to is currency.”

In other words, independent curators might be prized for their unique, niche insights into singular areas, even as those narrow specializations make it difficult for them to land positions at institutions.

Part of what a gallery, nonprofit, or art fair is tapping into when they hire an independent curator is also that person’s individual creative network—honed through years of networking, studio visits, parties, openings, and word-of-mouth referrals. Commissioning a freelancer to work with your institution can seem like renting that person’s knowledge, expertise, and hard-won contacts for a single project. “Contemporary art is a social industry, like politics,” said Stephen Truax, an artist, writer, and associate at Cheim & Read who also curates independently. “Who you know and whom you have access to is currency.”

The independent curator can then act as a middleman and a facilitator, plugging her existing network into new outlets. When private galleries are involved, that can mean straddling the commercial and creative fields. “It’s my job to create a rapprochement between institutions or galleries and artists,” said curator Aliza Edelman. “Further, curating demands a strong understanding of the art market, certainly not taught in graduate school, but imperative as someone navigating galleries.”

Each year, dozens of budding curators enter the field, graduating from specialized graduate programs like that at Bard’s Center for Curatorial Studies, launched in 1990, or earning credentials from institutions such as Rutgers and New York University, which offer certificates in Curatorial Studies in conjunction with doctoral degrees. (They also often amass significant debt along the way.) Most of the more than 15 curators interviewed for this story saw independent curating as a path to full-time employment, rather than a chance to become an eternal freelancer.

Burns has witnessed a similar dynamic in a broader sense. “It’s not specific to curators—it’s the case for all types of museum professionals,” he said. “We’ve seen a boom in museum studies and arts-administration graduate programs in this country like never before. And the fact of the matter is, there’s no way that the profession is generating enough jobs for all these graduates. A museum wants a Ph.D., [but that graduate] could make more money waiting tables. I think for a lot of students graduating today, it’s a very conscious decision for them to be freelancers; in some cases, it’s just more practical.”

Burns also chairs the American Alliance of Museums Curators Committee, and estimates that of their roughly 2,400 current members, one-quarter to one-third work independently. He said curators are experiencing the fate of exhibition designers, individuals who were previously charged with helping define the ways in which visitors engage with and navigate through a show, before them. “That’s been a sea change during my career,” Burns said. “In the early ’90s most museums had a full-time exhibition designer on staff. I wouldn’t say that’s unheard of today, but museums that do are in the minority now. And a lot of that works gets contracted out” for cost-saving reasons, he said.

Too often, actual labor is swept under the carpet, redefined as a “labor of love” or “passion project.”

U.S.-based organizations like Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) have made great strides for artists in cementing and promoting acceptable fee ranges for things like delivering a lecture or having one’s painting included in a group show. Similar efforts are underway by W.A.G.E. to help map a sustainable future for curators, but at the moment, conversations with those in the field point to wildly varying standards.

Lise Soskolne, the Core Organizer of W.A.G.E., also underlines a comparison between independent curators and their counterparts in academia. “Like the replacement of full-time, tenured faculty with adjunct labor in academic institutions in the U.S.,” she said, “there seems to be a turn in Europe toward replacing single, full-time curatorial positions with multiple, independent curators working on short-term contracts.”

Soskolne sees in this tendency an array of negative effects: “increased precarity, lack of benefits, and the debilitating and impossible process of cobbling together an income based on flat fees that bear no resemblance to the actual value of the labor, based on the hours invested.” One can only imagine that the situation in America—with a comparatively much flimsier social safety net—is equivalent.

“Curators, like artists,” she concluded, “are working well below the minimum wage.”

That dovetails with Jerry Saltz’s description of the art world as an “ALL-volunteer Army,” made of people who work for love, not money. That sentiment, while well-meaning, can also be problematic—a way to excuse a system that tends to underpay or exploit those who generate its actual value. Too often, actual labor is swept under the carpet, redefined as a “labor of love” or “passion project.”

View of Máret Ánne Sara, Pile o’ Sápmi, 2017, during installation at documenta 14, 2017. Photo by Candice Hopkins.

If the field is to approach sustainability, curators have to insist on being treated as professionals, which often means firm negotiations and data-sharing with others in the field. (In this regard, crowdsourced salary surveys—like one currently being conducted by POWArts—may be able to provide even more context.)

“For larger exhibitions like documenta 14,” said Candice Hopkins, who was on the quinquennial’s curatorial team, “that was a full-time job, so I negotiated for my salary to be the same as it would be working as a curator for a large institution. I have a tight network of other independent curators and we do share some details on fees, as it’s important that we be remunerated fairly. It’s still shocking to me that some people regard what we do as volunteerism.”

Still, other curators expressed a willingness to work for little (or for free) with the understanding that such gigs might lead to more profitable opportunities in the future. “I have, 100%, taken on unpaid jobs in the arts to build my resume,” said Robert Dimin, co-director of Denny Gallery and curator of shows like 2015’s “Made in New York” at Blueshift Project in Miami. “If I could work with certain artists in culturally important places with budgets to put together really amazing things—I could still see sacrificing payment for the success of the show.”

“Curators, like artists, are working well below the minimum wage.”

Others spoke of the way in which even poorly remunerated curatorial gigs might work to build a personal brand, in ways that could pay more generous dividends down the road. “I’ve worked on a few curatorial projects for free, and a few others essentially for free—less than $200 per project,” said Wendy Vogel, a writer, editor, and independent curator who has worked on a variety of projects, from co-curating a Parsons MFA exhibition in 2013 to overseeing a special section of the VOLTA Fair in 2017. “This is a huge problem within the field. I don’t want to contribute to a system that exploits creative labor. On the other hand, I’ve put myself into a really tricky spot as a curator. I feel a lot of pressure to bulk up my resume with more projects. This ambition or guilt is only enhanced by the culture of creative labor in New York, where the second question after ‘What do you do, and what are you working on?’ is ‘What else are you working on, what’s next?’”

Even if curators commit to only taking on paid work, however, simply setting an equitable price for the labor can be slippery. Curators are quick to note that plenty of what can be seen as socializing can also be defined as work. “It’s very difficult to actually account” for everything that goes into planning a show, Reyes Franco said. “There’s seldom a boundary between socializing, working, researching, or just having conversations. That’s why it becomes very difficult to assign value to what you do.”

Nearly all of the curators interviewed stressed that curating alone is rarely a path to financial security. Instead, curating jobs join other semi-related gigs that, together, hopefully add up to a paycheck. “I think it’s part of the multiple activities that someone in the creative fields has to take on, part of an aggregate of activities,” offered Michelle Grabner, an artist who has also co-curated high profile shows like the 2014 Whitney Biennial, and is serving as the artistic director of the forthcoming FRONT triennial.

Installation view of Michelle Grabner's floor at the Whitney Biennial 2014. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Those activities might include lecturing, teaching, writing for art-related magazines, contributing catalog essays for monographs, or other similar projects. As J. Simmz—co-founder of the independent curatorial platform Doppelgänger—aptly describes herself, most in the field are “roguish multitaskers,” adept at bouncing between related activities that inform each other.

Few curators saw the freelance path as sustainable in the long-term.

Some, like the multihyphenate artist, writer, and curator Keith J. Varadi, see curating as one additional component in a larger portfolio. “I’m not really sure if you can make a living,” he admitted. “All of the biggest names in the business are also connected to some museum or institution, which provides them with some level of stability and security—through a steady paycheck and other plusses, including the ability to globetrot and gallivant.”

Reyes Franco underscores the same point, noting that the division between the field’s superstars and its workaday practitioners can be extreme. She pointed to Jens Hoffmann, who—before allegations of sexual harassment surfaced in December of last year—had enjoyed affiliations with the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, the Jewish Museum, the Kadist Art Foundation, and the FRONT triennial in Cleveland, Ohio, to name a few. “That says a lot about the state of independent curating in general,” Reyes Franco said. “You have the concentration of power and wealth in a few people—and then there’s everybody else, active contributors to art scenes everywhere, but we get paid very little.”

Even with all of independent curating’s potential downfalls, many still advocate for the benefits of the job.

Aaron Levi Garvey—who co-founded the artist residency platform Long Road Projects, and recently organized a large-scale group exhibition at the Contemporary Art Center in New Orleans—values independent curation as part of a longer, well-rounded career. “I think of it as a rite of passage in order to find out what your curatorial vision and passion is,” he offered, noting that there’s a certain “stagnation” involved if someone has onlyworked in institutional capacities for their entire life.

“I love the work,” said Francesca Gavin, a writer and editor whose resume is very eclectic—from co-curating Manifesta 11 to helming shows at the Palais de Tokyo, as well as overseeing the Soho House art collection for years. “Coming up with a proposal, responding to a space, working with artists, unpacking and installing—it all feels like a privilege, to be taking ideas and manifesting them in physical space. Independence gives you more freedom to be experimental.”

“I feel that an institutional route could be safer for younger curators to follow, unless they’re willing to suffer a bit,” said Dimin. “But for me the suffering is fully worth it. I’ll need to organize shows, write poems, post on Instagram, and sell art—and if I’m lucky, as an old man, people will get me.”

“You have the concentration of power and wealth in a few people—and then there’s everybody else.”

“I am critical because I’m invested,” Mabey said, who joked that her peers often “slowly back away” when she brings up thorny issues of class and money. “This is my world and my life and I care so deeply about it. There are lots of wonderful things that come from working independently. I spent last January and February doing a residency in Santa Monica; if you have a full-time job, you can’t just take off and leave like that. I’ve worked with institutions of all sizes and have been able to do interesting, dynamic projects.”

In the end—while the field certainly needs more transparency, and equitable wages—quantifying personal and professional satisfaction isn’t always about simple arithmetic.

“I’ve always thought that if you want to be a curator—especially an independent one, without the job security of a museum structure—you’re fulfilled by your research, discoveries, engagement with artists, the magic of seeing a project come together, and the impact on others,” said Proch. “It’s meant to fulfill your curiosity.”

Scott Indrisek is Artsy’s Deputy Editor.

Cover image: ANDREA PATTARO/AFP/Getty Images.

No comments:

Post a Comment