These Artists Show Why Our Most Creative Years Often Come after 60

Portrait of Etel Adnan courtesy of the artist.

Portrait of Etel Adnan courtesy of the artist. Portrait of Jack Whitten by John Berens. © Jack Whitten. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Portrait of Jack Whitten by John Berens. © Jack Whitten. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The late phase of an artist’s work has always been a source of fixation for the art world. The work successfully executed in one’s golden years is often seen as proof of greatness, the climax of a life of learning, bestowing upon the artist the status of sage creative genius.

It’s a phenomenon that’s been achieved only by the (male) giants of the Western canon: the white-bearded, godlike Titian, using only his fingers to apply paint as his apprentices looked on in wonder, or the wheelchair-bound Matisse, making art from paper and scissors and surrounded by comely female assistants.

In recent years, much has been done to rectify this bias, and the virtues of mature work by artists such as Louise Bourgeois have been extolled. The French-American artist, who died at the age of 98, employed her late work to speak for the LGBT community, donating editions of a print titled I Doto the Freedom to Marry campaign in 2010—and has been praised for it.

Today, there is an increasingly diverse range of living artists who are receiving recognition for their late work. One such example is the nonagenarian artist Elisabeth Wild, who emigrated from Europe to Argentina in the late 1930s, where she studied painting at the Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes and then earned her living by designing textiles.

She now lives in Guatemala with her daughter, the painter Vivian Suter, where they have shared a studio for over 30 years. Their paintings and collages have been shown together at Kunsthalle Basel, and most recently at Frieze London.

Now retired from textile manufacturing at age 95, Wild is more prolific than ever. “I have time, more freedom, and less pressure, and I try out things that I probably wouldn’t have at an earlier age,” she says.

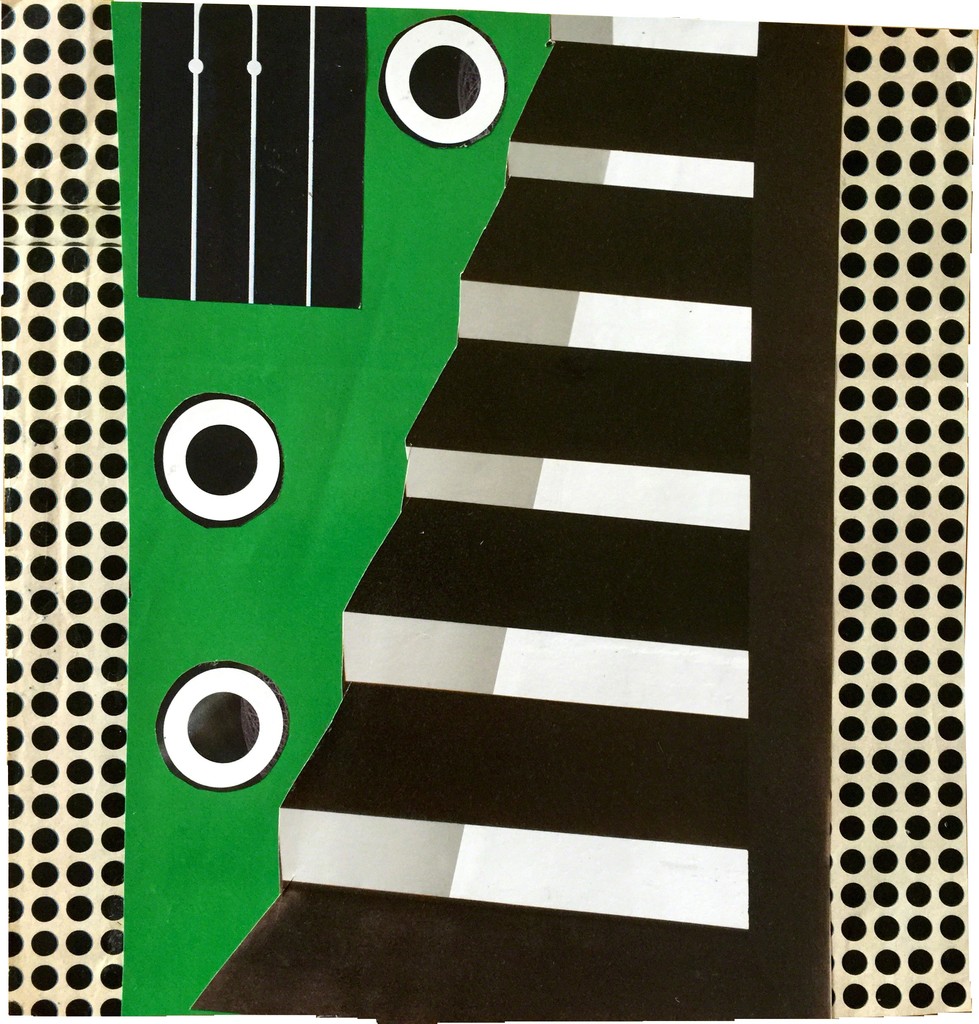

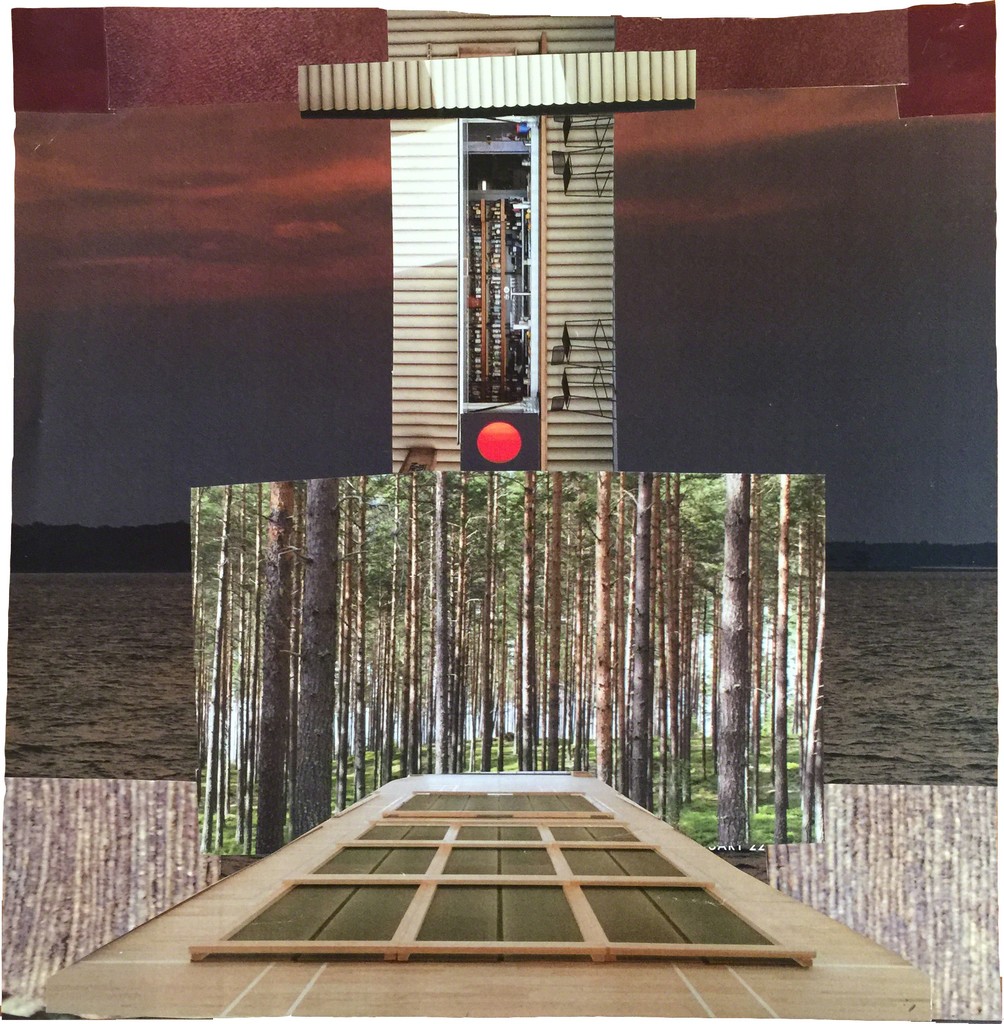

In recent years, Wild has been working from a wheelchair and she has exchanged her paintbrush for a pair of scissors. “I broke my hip 13 years ago, and I find it difficult to paint like I used to,” she says. “I found collage-making better suited for my mobility given that all I need for this is my hands, my mind, my scissors, and glue.”

These collages, recently on view at Greengrassi in London, are pieced together from design magazines to create surreal, mosaic architectures replete with disappearing staircases and vanishing walls. Unlike Matisse, whose assistants prepared large colored sheets for him to cut into, Wild works alone, and her rather smaller clippings are set down on sheets of notebook-sized paper.

“I enjoy making collages, and I do it because I like to, not because I have to,” says Wild. “I feel confident. I feel creative. That is enough.”

For another nonagenarian, the Lebanese-American artist Etel Adnan, the presiding spectre of mortality has become a major impetus behind her work. “I am aware that time is running short, that any work may be the last one,” she says from her studio in Paris. “I live with a great feeling of urgency.”

Only five years ago, Adnan was best known as a writer and poet, but it is her small-scale landscape paintings, simple patchworks of color made by applying oil paint with a pallet knife, that have now come to prominence. First shown at dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012, they have since been hung at the Serpentine in London and at FLAG Art Foundation in New York.

Adnan’s vivid, sensual paintings counter her fierce, polemical writings. “Along the way, it just so happened that my visual works were rather hedonistic,” she says. “Painting ended up reflecting the happy side of my nature, a deep-down optimism that keeps me alive and active.”

By contrast, Adnan’s writing engages with difficult subject matter. She has written texts on gender and feminism, and is recognized for her dispatches from the Lebanese Civil War, including the novel Sitt Marie-Rose (1978), based on the life of a woman kidnapped and murdered during the conflict.

Her poetry, meanwhile, continues to reflect on the political turbulence of the Arab world, and her latest volume Premonition (2014) is a fractious poem that muses on human unpredictability.

“While my paintings have not changed much along the years, my latest works of poetry are very consciously more philosophical,” Adnan says. “It is as if, before disappearing, I want to catch some truth, something crucial—some vision.”

For the African-American painter Jack Whitten, too, a sense of impermanence drives his work. “For anyone who turns 70 in the arts, it is always a question of mortality,” he says. “How many years do we have left? This forces you to get rid of all leftover, unnecessary elements and to deal with only that which is important.”

Moving to New York in the 1960s, Whitten was an active participant in the Civil Rights movement before he turned to painting, befriending the Abstract Expressionist artists Willem de Kooning and Norman Lewis. It was in the 1970s that Whitten made a name for himself, and he is one of the few African-American artists to be associated with mid-century abstraction.

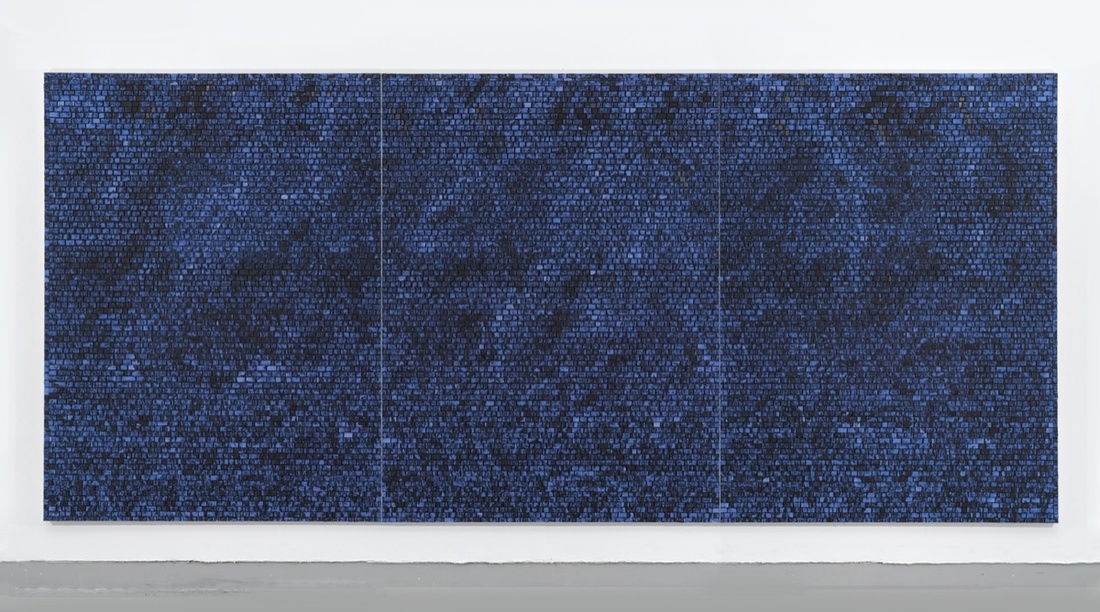

He developed a technique of casting acrylic paint into tiles before applying them to the canvas, creating works that occupy an unusual position between painterly and plastic, abstract and concrete. As with Whitten’s ongoing “Black Monolith” series (1990–present), it is the titles that politicize the works, paying homage to black artists of the last century.

“Politics has always been a necessary irritant, like an itch that I have to scratch,” says Whitten.

Jack Whitten, Quantum Wall (A Gift for Prince), 2016. Friedrich Christian Flick Collection. © Jack Whitten. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Jack Whitten, Quantum Wall (A Gift for Prince), 2016. Friedrich Christian Flick Collection. © Jack Whitten. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The unreadable mosaic figure in Black Monolith II: Homage to Ralph Ellison, The Invisible Man (1994) is assembled from tiles of acrylic mixed with molasses, copper, salt, coal ash, chocolate, onion, herbs, eggshell, and razor blades, as Whitten commemorates the unnamed and abject protagonist of Ellison’s novel. The latest in this series, Black Monolith X, Birth of Muhammad Ali (2016), is part of a new solo show at Hauser & Wirth in New York.

Artists who have become popular for a particular style but who change tack late on are liable to fall out of favor with critics and viewers. Mondrian caused uproar with his last painting, Victory Boogie Woogie(1942–44), which marked a final shift away from geometric abstraction.

Not so with Whitten, who has remained consistent in his investigation of the acrylic tile. “My work ethic has been the same for over 50 years, and I don’t find my recent works any different from other works I have made,” says Whitten, “They still express the same quality of attention and control of medium.”

He is now working on two new series, “Portals” (2015–17) and “Quantum Walls” (2016–17), both of which use the acrylic tile to express the unknowable shades of quantum matter. And Whitten has been receiving considerable recognition into his later life, including prestigious lifetime awards: the Aldrich Museum A2A Award this January, and the National Medal of Arts awarded by President Barack Obama in 2016.

“The only difference I feel is a state of maturity,” Whitten says. “And I feel that I’m a better painter for it.”

American photographer Rosalind Fox Solomon has also been hard at work well into her twilight years. She is known for surreal and unsettling photographs of beauty queens and mannequins that caught the public eye in the 1970s. She went on to make a powerful and political series, “Portraits in the Time of AIDS,” in the late ’80s, which brought a humanizing lens to the AIDS crisis.

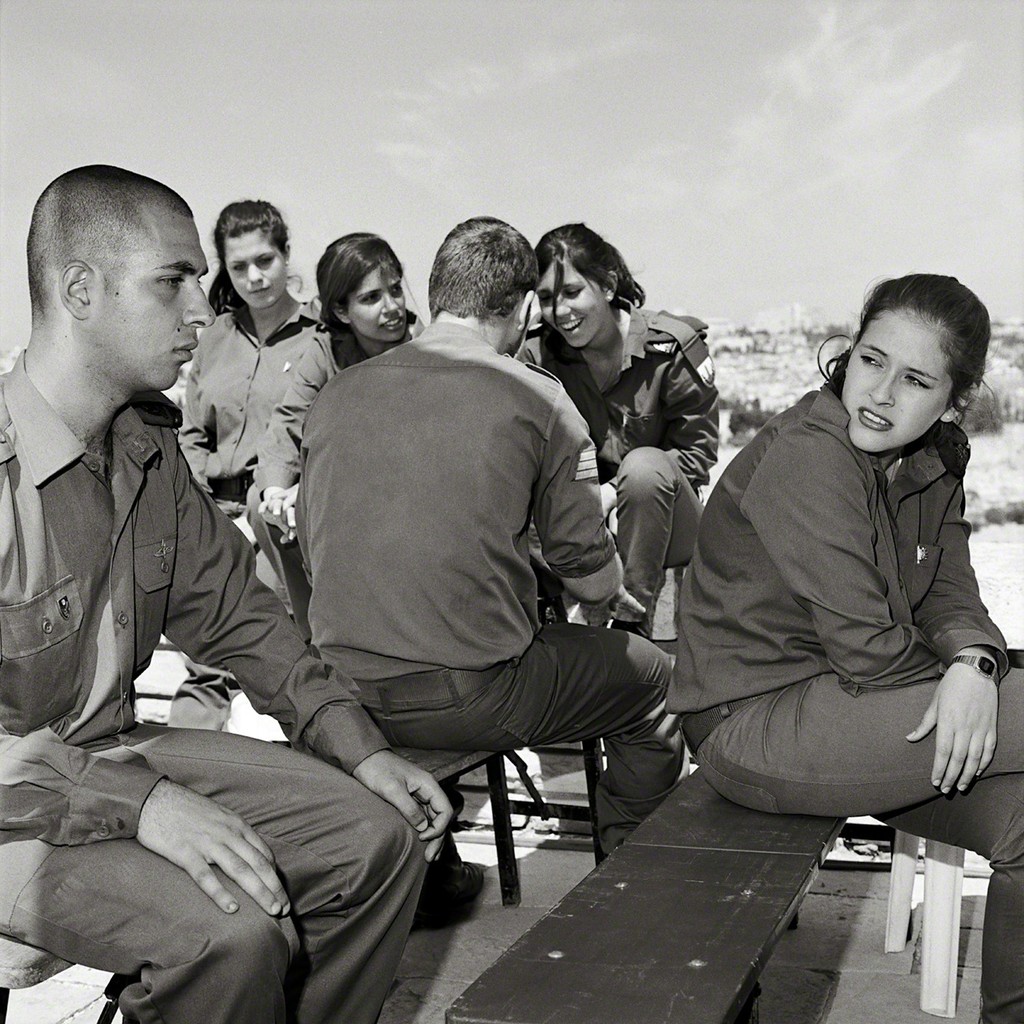

Now 86, she is engaged in a double process of making new work and, at the same time, reaching back into her archive. In 2010 and 2011, she visited Israel and the West Bank to make portraits of a fractured society, taking photographs on local buses, at sites of worship, and in the intimacy of living rooms.

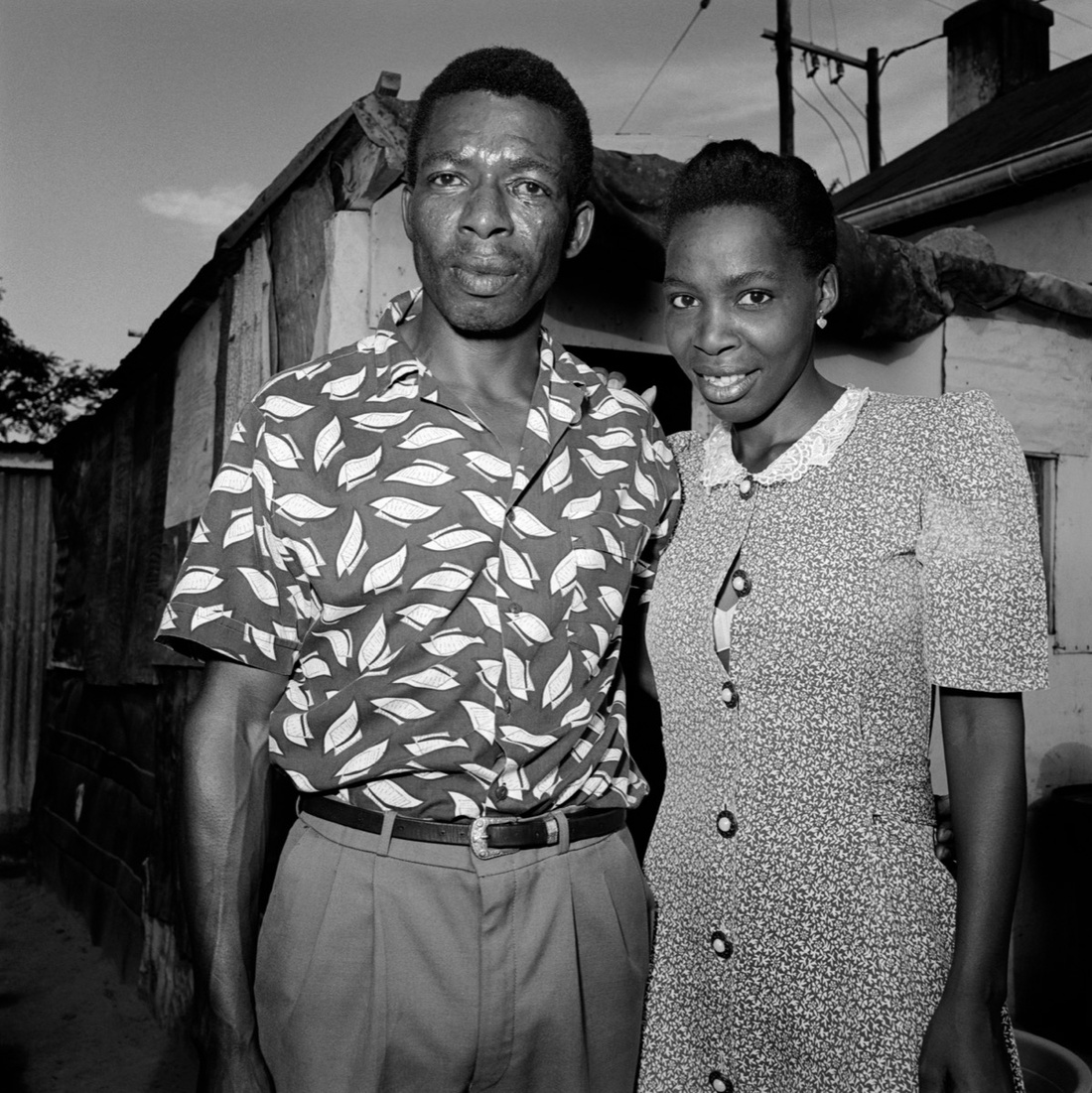

Photograph by Rosalind Fox Solomon, from Got To Go, MACK Books, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph by Rosalind Fox Solomon, from Got To Go, MACK Books, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

At the same time, she has been returning to her opus and reaping new fruit. “I am re-visiting chapters of my life,” she says in reference to her most recent book, Got to Go (2016), which hovers somewhere between photo-memoir and fiction, combining her own autobiographical photographs with others borrowed from past series.

“Dissemination of the work has become one of my paramount concerns,” she says. “I am not a spring chicken, but my creativity continues to empower.”

One might expect an artist’s mature work to express serenity or resolve, but Fox Solomon’s late works embrace difficulty, contradiction, and opposition. Rather than retreating from the political sphere, she continues to lock horns with political injustice.

“My interest in international human rights have informed my work for years,” she says. “With Donald Trump’s edicts, it looks like fascism and chaos are going to be a way of life. My work will be affected by this.”

Her main concern is to persevere. “When I was 60, people asked, ‘Are you still doing it?’ In December, I spent two weeks photographing in Havana and came back with good pictures. In other words, I’m still doing it.”

—Izabella Scott

No comments:

Post a Comment