David Hurn and Martin Parr: How to Build an Art Collection by Swapping Prints

Ahead of the opening of David Hurn’s Swaps exhibition, curated by Martin Parr, the Magnum photographers and print aficionados share their love for photography and their passion for collecting

Magnum Photographers

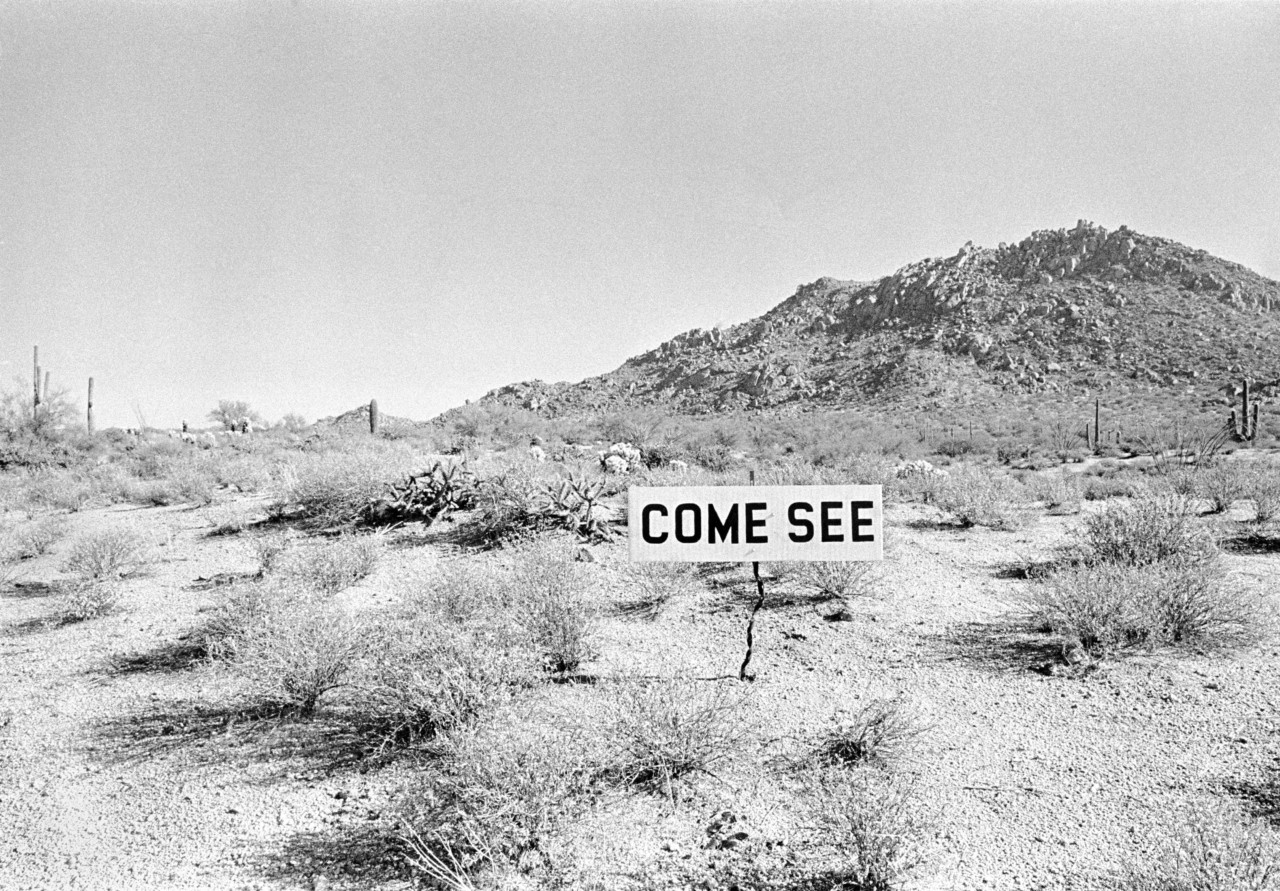

David Hurn A sign in the Arizona desert. It means that very shortly the whole of the area will be developed with housing and shopping Malls. USA, 1979. © David Hurn | Magnum Photos

License |

Eve Arnold American actress Marilyn Monroe portrayed in the bathroom of Chicago O'Hare airport, while waiting for a plane to Champaign, Illinois, where she was to attend the centenary celebrations of the town (...)

License |

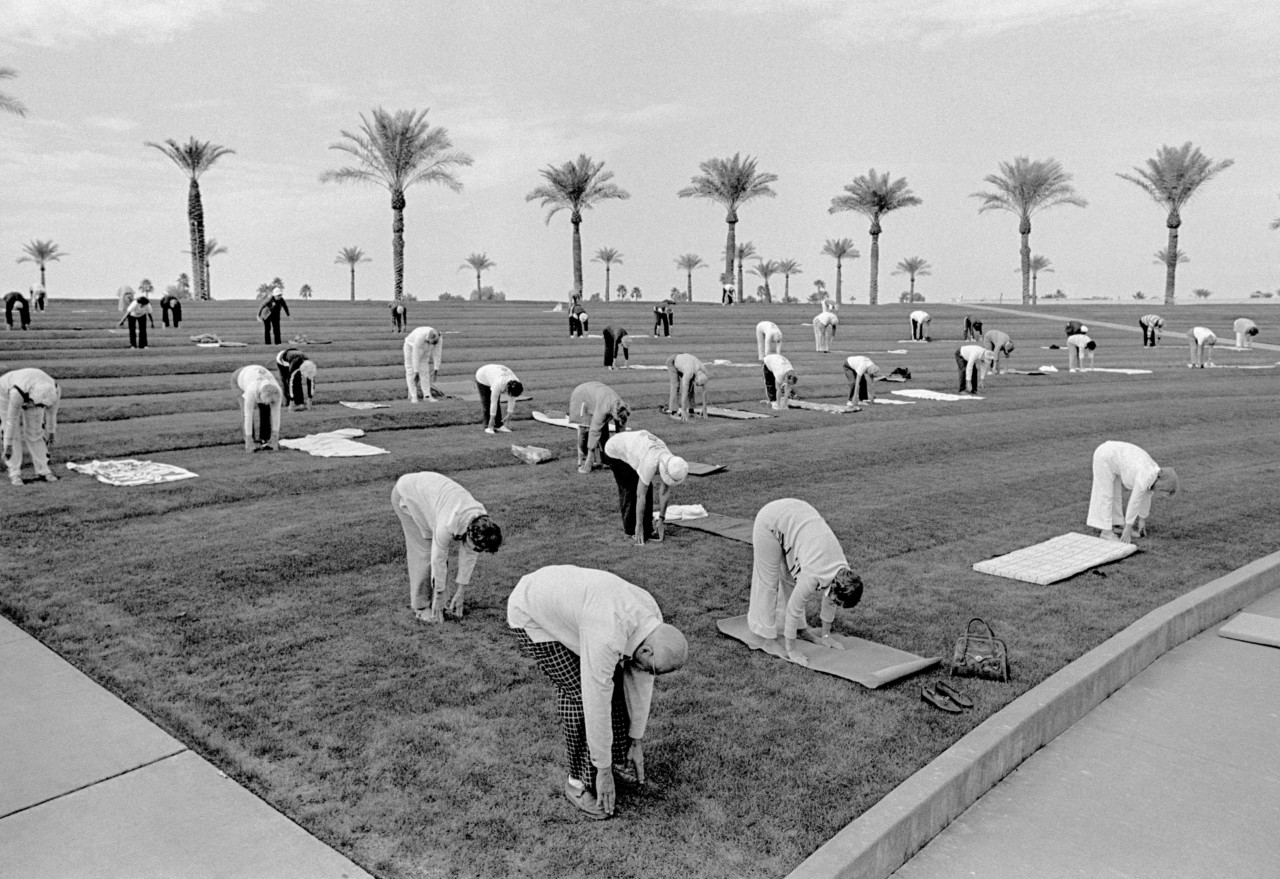

David Hurn Outdoor group fitness early in the morning in the retirement Sun City, Arizona, 1980. © David Hurn | Magnum Photos

License |

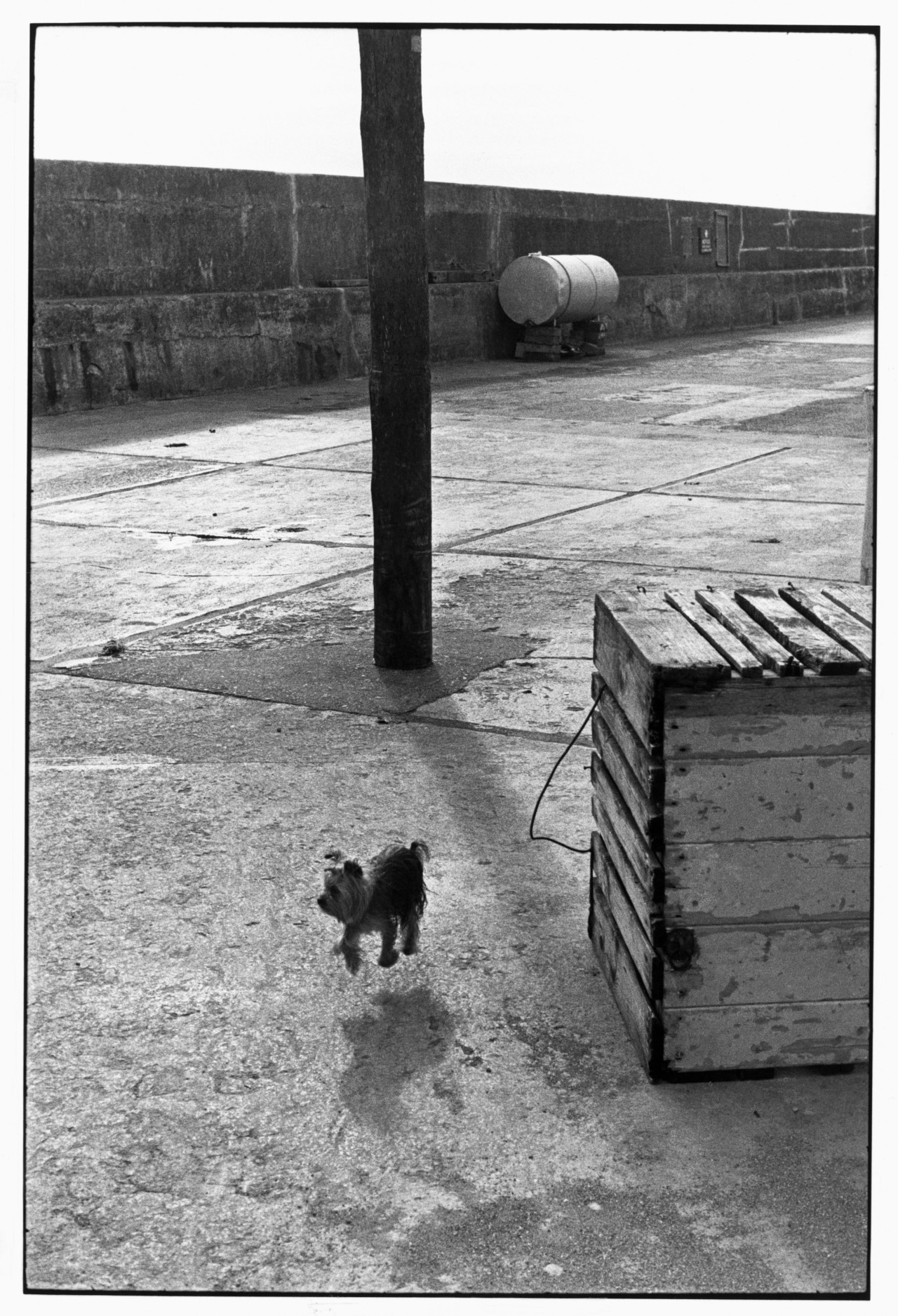

Elliott Erwitt IRELAND. 1968. Ballycotton. © Elliott Erwitt | Magnum Photos

License |

Josef Koudelka Invasion by Warsaw Pact troops near the Radio headquarters. Prague, Czechoslovakia, August 1968. © Josef Koudelka | Magnum Photos

License |

Henri Cartier-Bresson French painter Henri Matisse at his home, villa "Le Rêve". Vence, France, February 1944. © Henri Cartier-Bresson | Magnum Photos

License |

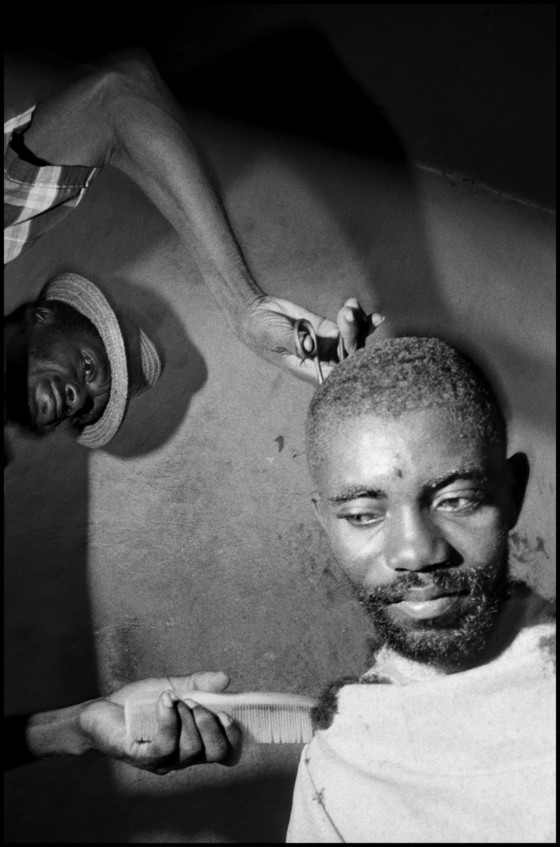

Alex Webb Etroits, La Gonave, Haiti, 1986. © Alex Webb | Magnum Photos

License |

"I don’t believe we’re unimportant, but I don’t think we should get too pompous"

- David Hurn

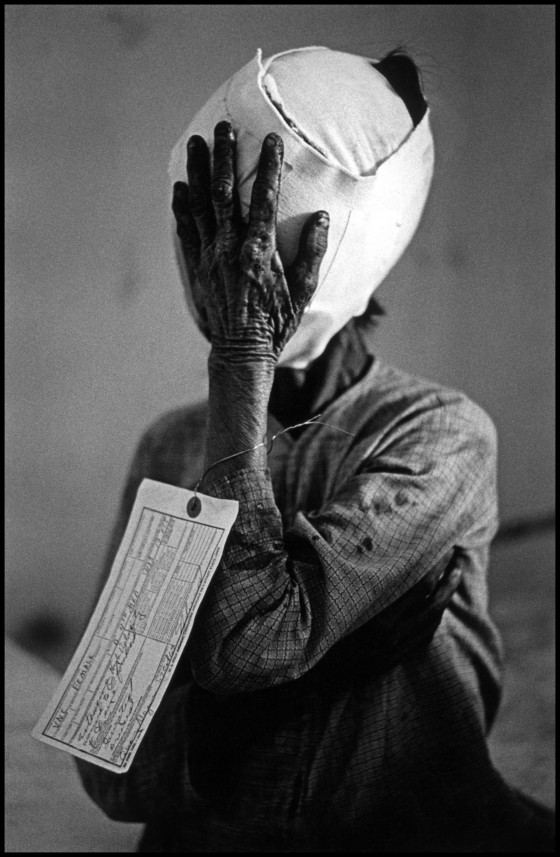

Bruce Davidson Welsh miners, Wales, 1965. © Bruce Davidson | Magnum Photos

License |

No comments:

Post a Comment