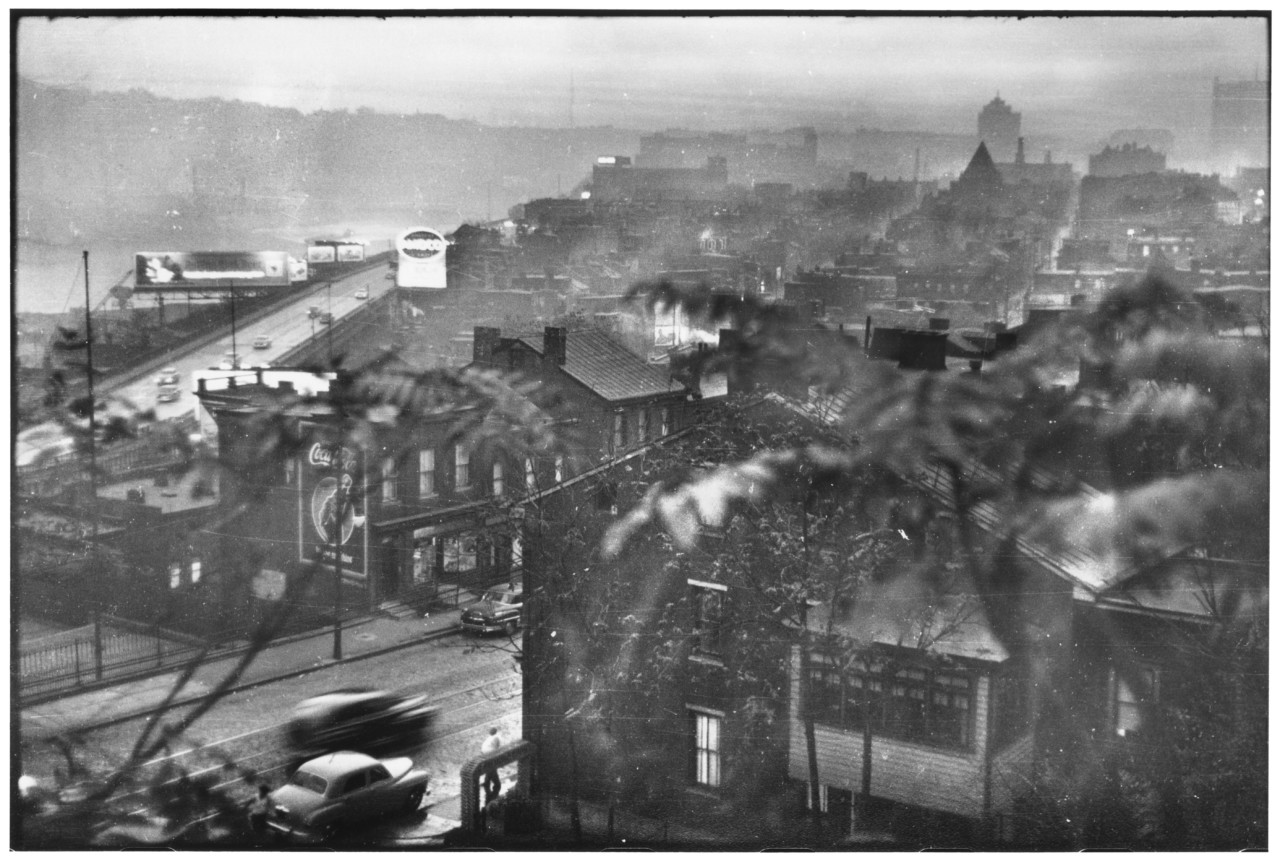

“Everything was grand, heroic. Everything seemed to be gigantic in Pittsburgh—the people, the history. Sinuousness. Power. Substance. Meaningfulness.”

— Pittsburgh-born poet Jack Gilbert, in a 2005 Paris Review interview

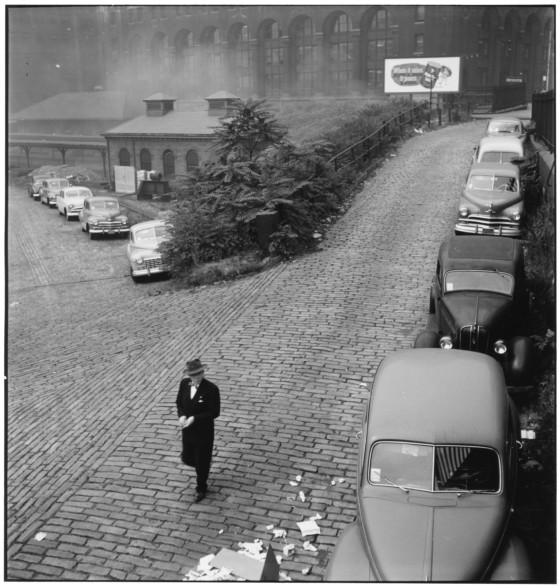

At the time Erwitt arrived in Pittsburgh, Stryker was tasked with a commission by the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, a project that aimed to document the City of Bridges at mid-century. The ACCD envisioned a far different postwar Pittsburgh than the bleak mill towns of popular imagination. In place of a Pittsburgh defined by steel manufacturing and smog that dimmed the midday sun, the ACCD saw a remade city of glass and gloss, and even greenery: a cultural and academic center in its own right, made modern by far more than the heavy industry that gifted Pittsburgh its legacy. Planners hoped to endow the downtown core with a post-industrial sophistication – but they also knew that bringing dreams of this sort to fruition came with a heavy public cost. They recognized the need for a stirring, methodical photographic documentation of the transition from the old Pittsburgh to the new.

That task, at once colossal and intricate, fell to Stryker, who called in photographers from around the nation to join the newly formed Pittsburgh Photographic Library (PPL), headquartered near the top of the 42-story gothic revival Cathedral of Learning on the University of Pittsburgh’s campus. Erwitt joined a rank of colleagues that included James P. Blair, Esther Bubley, Harold Corsini, Arnold Eagle, Regina Fisher, Clyde Hare, Russell Lee, Sol Libsohn, Fran Nestler and Richard Saunders, all tasked with creating a collective portrait of the city’s rebirth. By the project’s end, some 18,000 negatives filled the PPL’s files.

As in his prior endeavors – whether under the employ of the federal government or in his role from the mid- to late-1940s at Standard Oil, for example – Stryker created elaborate scripts that hit the visual notes he wished to see brought forth in the story’s telling.

But for reasons no one – including Erwitt – quite gleaned, Stryker never demanded that Erwitt himself pursue specific narratives; instead, he gave the young photographer relatively free rein to document postwar Pittsburgh in his own way, with his own eye.

All these years later, Elliott Erwitt – now some seven decades past his months in Pittsburgh, recalls the Steel City in terms that have more to do with the ear than the eye. “I think Pittsburgh has a sound,” Erwitt says. “Pittsburgh conjures up something. Maybe it’s just the name – but I don’t know Springfield would do the same.” Roy Stryker first met Erwitt, then just 21, in New York in the spring of 1950 through a fortuitous introduction by the great Edward Steichen. (Erwitt had met Steichen, Robert Capa – who later invited him to join Magnum – and other major figures during “exploratory trips” to New York in the earliest days of his career.) Impressed by Erwitt’s work – or perhaps, more accurately, by the potential and drive he saw in the well-traveled young man – Stryker pulled a $100 bill out of his pocket at their meeting and sent him off on a short assignment: to photograph an oil refinery in New Jersey. A few months later, he invited Erwitt to Pittsburgh.

The fall of 1950 proved a rewarding and formative time for Erwitt. From September through December (when he received his draft notice from the U.S. Army), Elliott fervently documented Pittsburgh and its people.

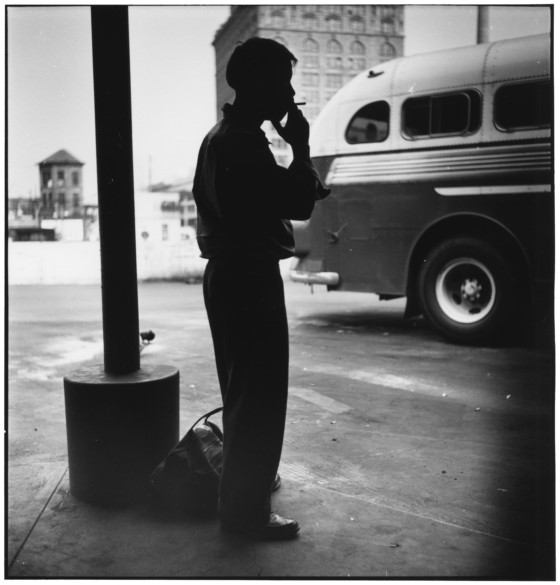

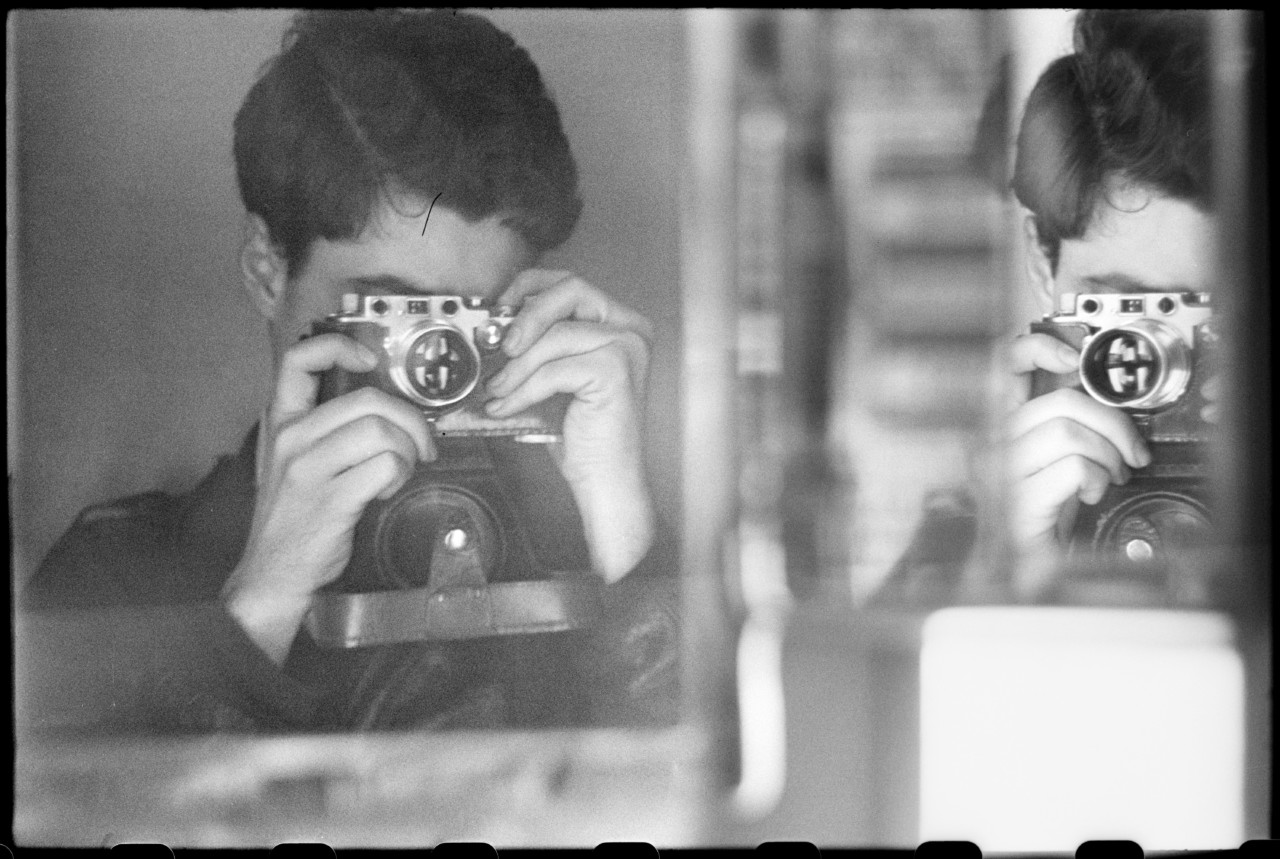

Armed with a Leica IIIC and a Rolleiflex, he thrived on Pittsburgh’s streets and in its neighborhoods scattered along the hillsides lining the city’s three rivers. Returning regularly to the PPL offices, he developed his photos in the Library’s darkroom, picked up more film and eagerly returned to the streets. Stryker reviewed Erwitt’s works with a characteristically discerning gaze, carefully sorting the images and selecting those that, to his mind, were useful in advancing the message that the ACCD had hired him to articulate in pictures.

Negatives that failed to meet the rubric set forth in Stryker’s script or his mind were “killed.” In past projects, unsanctioned or unapproved photos under Stryker’s hand had not just been cast aside: they were physically (and disappointingly) hole-punched, rendering them forever unusable.

But in Pittsburgh, Stryker filed unharmed negatives away in boxes marked “K” – the kill file – making the Pittsburgh project one of the very few in Stryker’s long career for which researchers can view the entirety of the collection. In this case, that entirety amounts to a trove of roughly 18,000 negatives. Many of Erwitt’s negatives were slated to be “killed,” but survived – negatives that, long forgotten and long unseen, now emerge in this book from the murk of the intervening decades. It’s in this kill file that we find some of Erwitt’s most compelling frames.

Stryker, it seems, didn’t always see the same value in Erwitt’s singular, spontaneous documentary style that we celebrate today. Much of Erwitt’s work in Pittsburgh falls under the PPL subject file “human interest” – an ironic understatement of Elliott’s timeless visual approach to the world.

Erwitt’s contact sheets from the fall of 1950 make clear and amplify his interest in the Pittsburghers he met and photographed while witnessing the transformation of their neighborhoods and their city. Furthermore, his surviving pictures testify to the way that he homed in on the distinctive human experiences he encountered – and that obviously so moved him – in the quintessentially American postwar city.

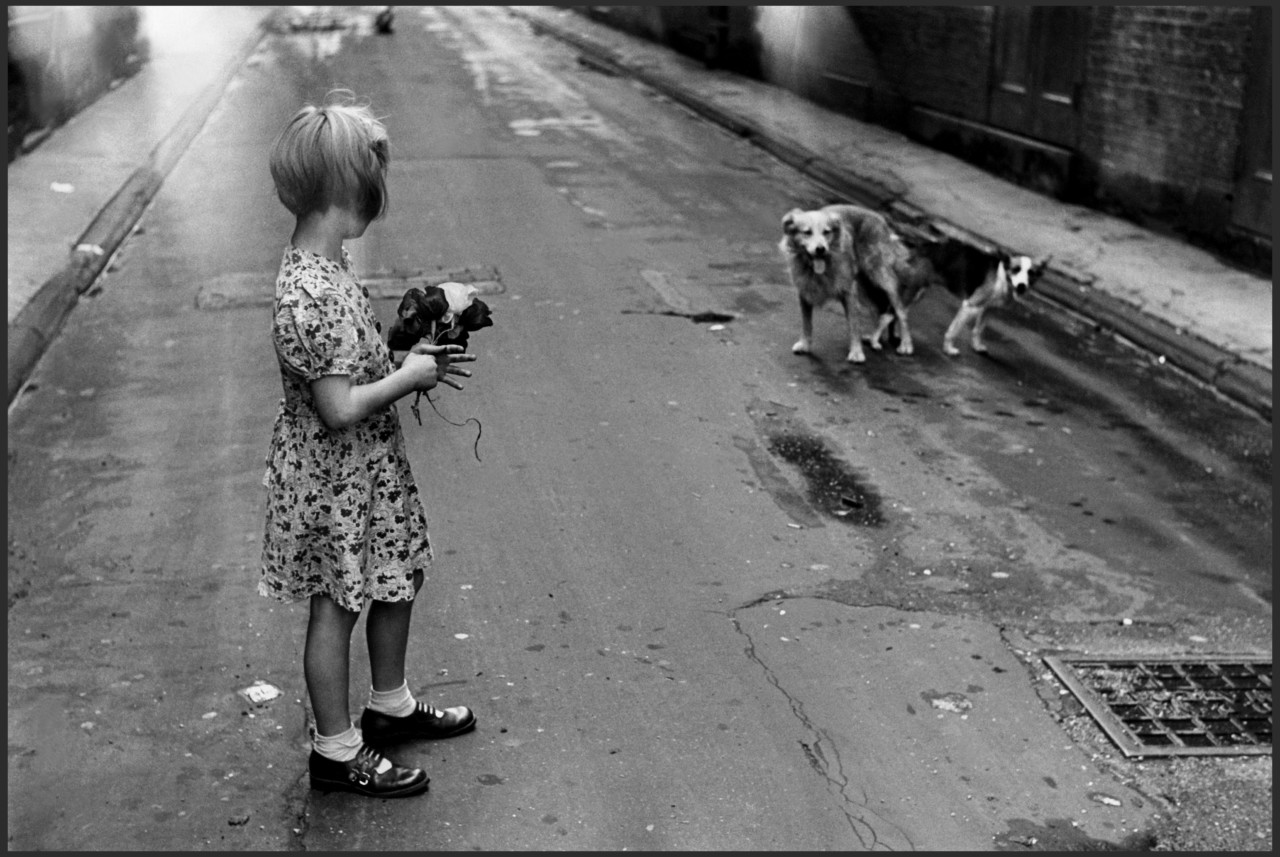

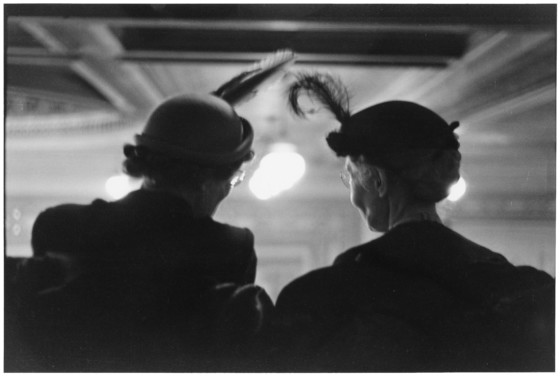

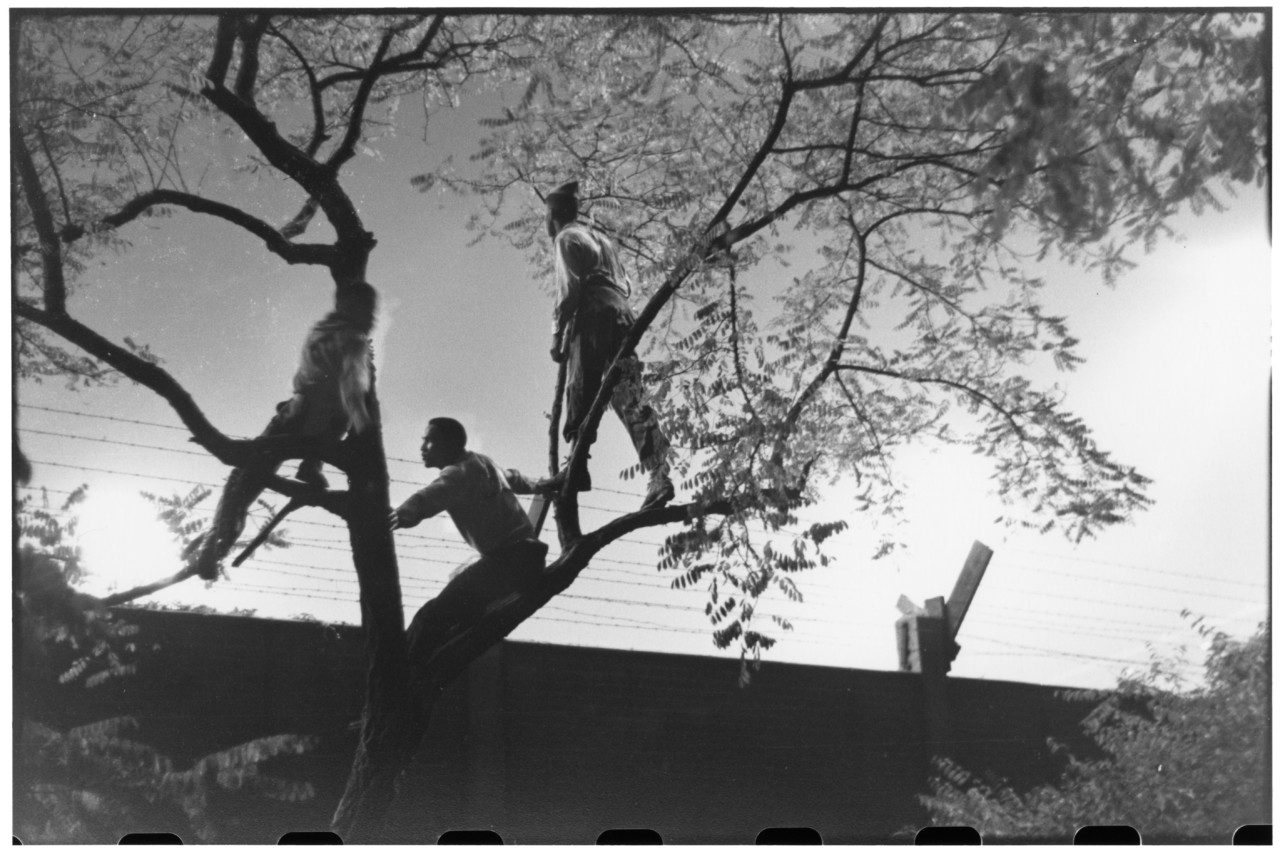

Erwitt spent time photographing the staples of life in Pittsburgh, mingling with the crowds at the Armistice Day parade or at baseball games at Forbes Field. Interspersed with the wholly expected documentary scenes are pictures that evince the lightness and even the quirkiness that we have come to expect from Elliott.

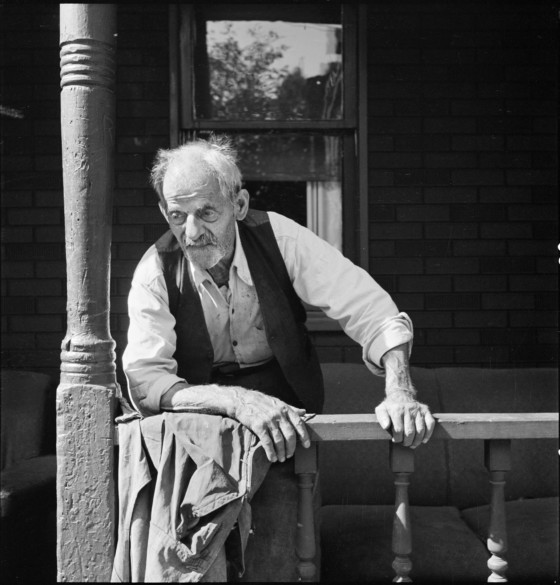

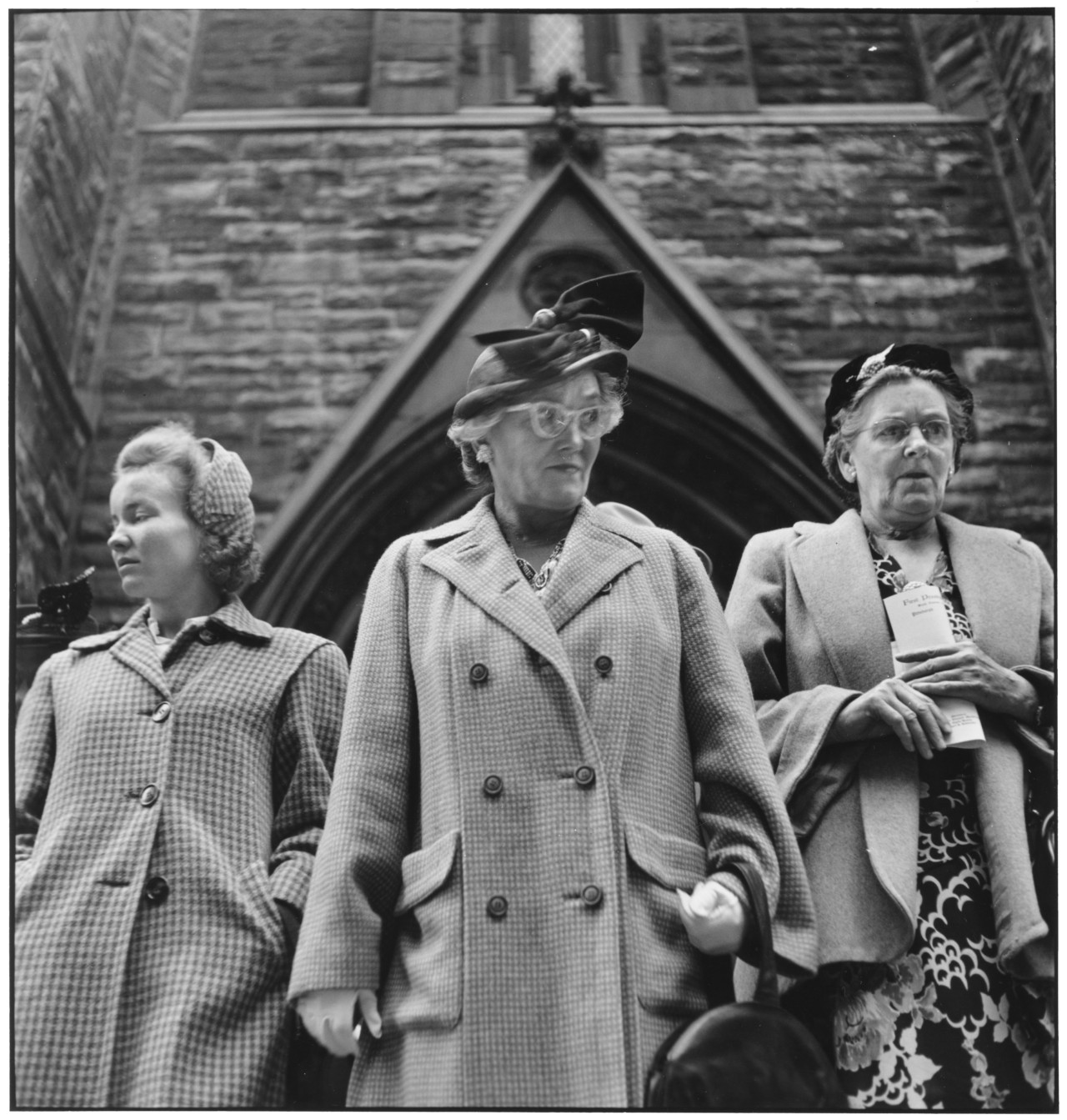

One Sunday afternoon, Erwitt pauses to capture well-dressed women descending the steps of their church. In their church outfits, they glare into the lens – their displeasure (almost comical, all these years later) at Erwitt’s intrusion into their quiet world captured by his perceptive eye – and yet Erwitt’s photograph of an elderly woman doing just that is recognizable as a scene played out daily throughout the city’s neighborhoods, in an era when an hour or so spent with a newspaper was a Pittsburgher’s way of connecting with the wider world – and the Pirates’ box scores. The housing stock, the porch, the woman’s expression: it all feels exactly as it should, within the context of the picture’s time and its place. Curious and purposeful, wandering and driven – Erwitt’s work in Pittsburgh, so early in his career, represents the very genesis of what we now recognize as his visual signature.

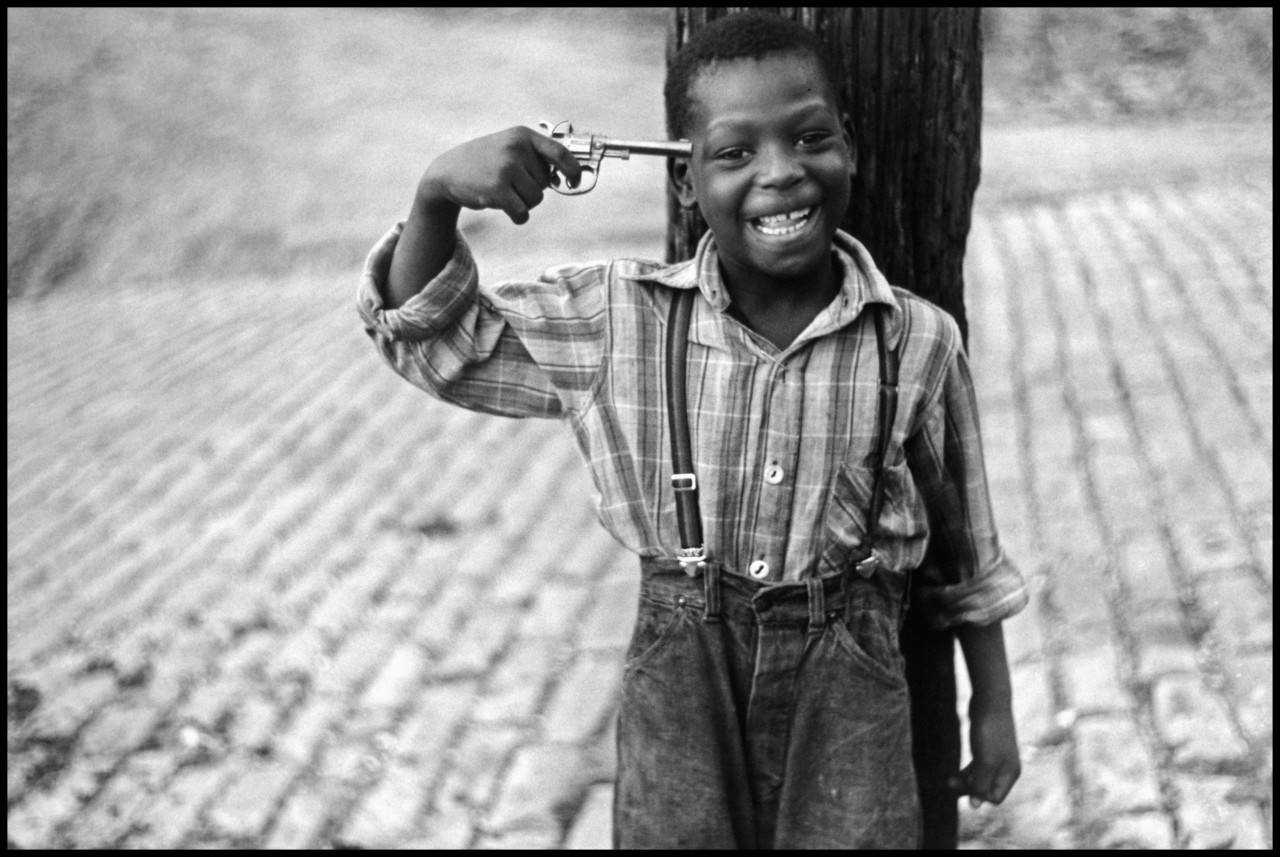

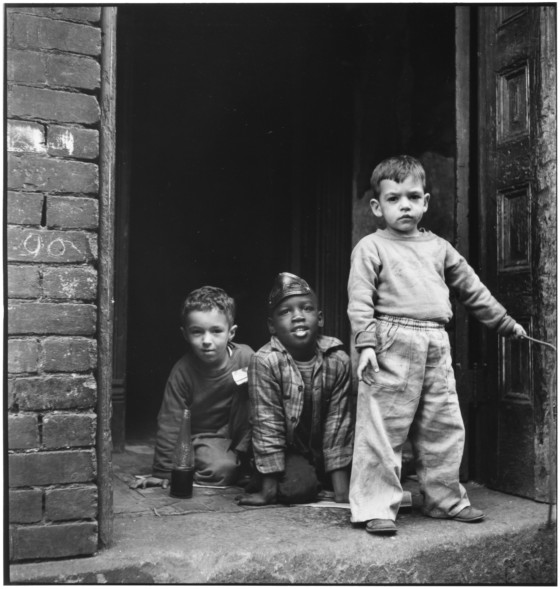

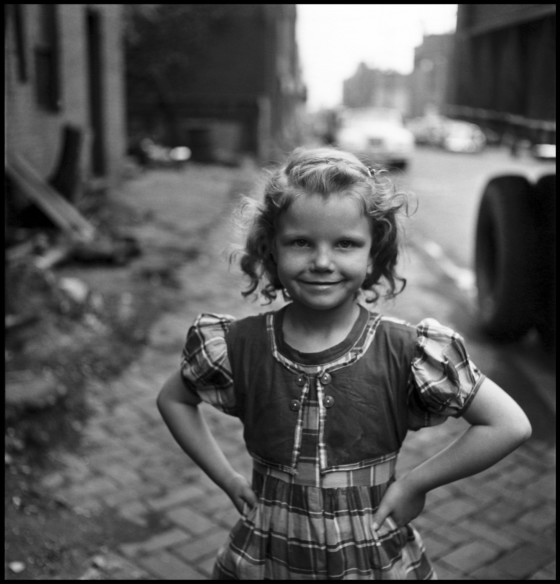

Many of Erwitt’s days were spent photographing the children of Pittsburgh. Young photographers often gravitate towards children as subjects – kids are, by their nature, spontaneous, energetic, charismatic before a lens – but Erwitt’s images of children offer what amounts to a remarkably nuanced look not only at childhood, but race relations in the Steel City of the early 1950s.

One of Erwitt’s most enduring images from this time is of a young African-American boy in the Hill District pointing a toy gun at his own head. The Hill, as it was known, stretched from the city’s downtown up through black residential and business districts clustered along Wylie Avenue. The neighborhood, known nationally and in jazz circles as the “crossroads of the world,” offered black residents an economic and cultural sanctuary. City developers, meanwhile, focused on the area as a prime location for redevelopment and the choice home for the new Civic Arena. Citing poverty and vice in the district – problems that, strangely enough, seemed to largely evade the notice of city fathers in previous decades – developers and city agencies eventually moved more than 8,000 residents off the hill and into surrounding suburbs.

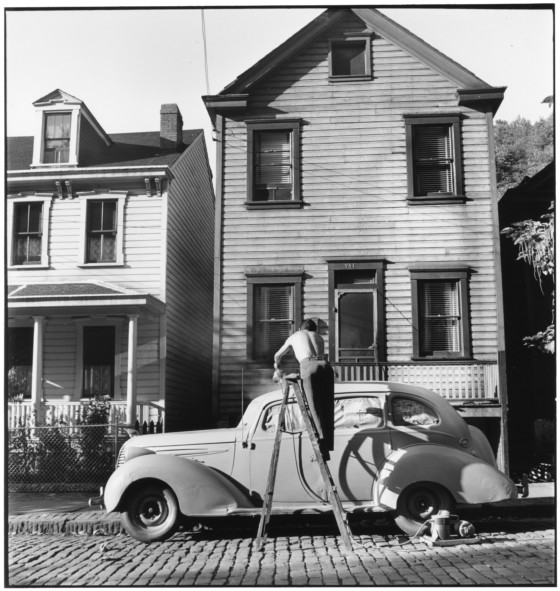

The Pittsburgh of an earlier time – gritty, proudly blue collar, industrial and dynamic – was transitioning, by fits and starts, to a new incarnation. Today’s Pittsburgh – a 21st century study in how a city reinvents itself – was born, or at least conceived, right around the time a young Elliott Erwitt was setting forth each day, cameras in hand, from his one-room rental at the YMCA.

The pictures in this book represent work spanning just four short months – an ellipsis in Erwittt’s long life and career. Erwitt departed Pittsburgh in December for a stint in the Army, and Stryker’s PPL continued its mission until 1953. As funding dried up, Stryker left to direct a project for the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation and the group eventually disbanded. The photographs eventually made their way to the Pennsylvania Department of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, where they have resided, largely undisturbed (until I began to quite happily dig into the collection while researching this book) since the late 1950s.

Anyone who has long known Pittsburgh can see glimmerings of today’s reinvented city in the photographs Erwitt made during those four months in late 1950. Today’s Pittsburgh is a city transfigured – and a place where history has not yet been utterly erased. The singular spirit of Pittsburgh’s people and so many of its public spaces has endured throughout generations. That’s a special kind of magic. And as the eloquent pictures in this book attest, the young Elliott Erwitt performed a kind of magic of his own: he brought that spirit to light.

This text was written by Vaughn Wallace for the introduction to Pittsburgh 1950, published by GOST in September 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment