| |

| |

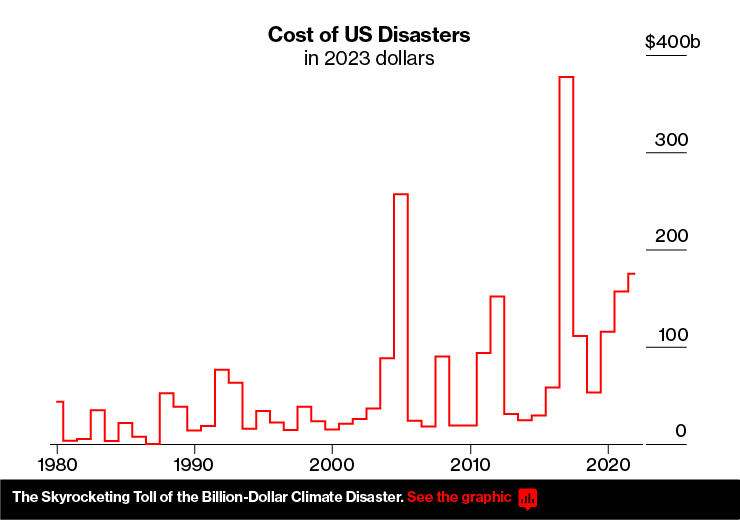

When Farmers Insurance Group on July 12 said it would stop writing new homeowners policies in Florida, it became the 15th insurer in the state to take that step since early last year. Florida officials fault widespread insurance fraud for the exodus, but Farmers said it needed to “manage risk exposure” in a place where climate change threatens more natural disasters.

Florida’s slow-motion insurance meltdown is happening as new people pour into the places with the greatest risk of flooding, a pattern playing out across the US. Almost 400,000 more people moved into than out of the nation’s most flood-prone counties in 2021 and 2022, double the increase in the preceding two years, according to real estate firm Redfin Corp. Counties vulnerable to wildfires and heat have also seen more people arrive than leave.

Insurance cost is the main way the market signals risk to homeowners. Yet in California, Florida and Louisiana the markets are flashing warnings that homeowners are largely ignoring. “There are definitely disruptions in the feedback loop,” says Nancy Watkins, an actuary at Milliman Inc., an insurance consulting firm. Why aren’t property owners taking the hint?

● A Fundamental Mismatch

Mortgages last 30 years, while insurance premiums are adjusted annually. When the climate was stable, Year 1 was a pretty good predictor of Year 30. But rapid warming means the perils are constantly growing, so the premium for the first year could be wildly off 10 years later, leaving homeowners at risk of far higher premiums later on. “The entire system is predicated on climate stability,” says Spencer Glendon, founder of Probable Futures, a nonprofit dedicated to climate literacy. “I think we can expect that nexus to break down soon.”

● Demographic Danger

Many people moving to risky areas are retirees thinking about little more than warm weather and lower taxes “who accelerated their retirement plans,” says Benjamin Keys, a professor of real estate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “They haven’t experienced a weather disaster.” It doesn’t help that most people—and developers—have short memories about destruction. Or that building codes and zoning can’t keep up.

● Information Breakdown

Even when buyers seek reliable information on long-term risk, it’s hard to find, with some government maps of severe flood zones dating to the 1970s. Homeowners in those areas must purchase flood insurance to get a federally insured mortgage, but people outside the zones—or those who own their home outright—have no such requirement. First Street Foundation says some 6 million homes that should be considered at severe risk of flooding lie outside those zones. And Milliman estimates there’s $520 billion of unpriced flood loss in the housing market—a number that will only increase.

Then there’s the question of how much insurance should cost. Carly Fabian of consumer-rights group Public Citizen says buyers deserve access to average home insurance prices by ZIP code over time, which would help them assess where insurers believe risks are spiking and whether they’re paying inflated rates. But insurance companies have blocked such efforts, saying the information is proprietary. “They’ve proven unreliable narrators on climate,” Fabian says.

● The Government Backstop

In the 1960s private insurers largely pulled the plug on residential flood coverage, deeming it too risky. The federal government stepped in with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which racks up about $1.4 billion a year in losses because it can’t charge market rates. Similar state programs in California, Florida and Louisiana only insure homes that can’t get private coverage, but with insurers backing out, they’re adding customers rapidly. Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corp. is already the largest single insurer in the state.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is promising reforms that will bring NFIP premiums more in line with climate risks, but Keys is skeptical. “It’s like a dad threatening to turn the car around when the kids aren’t behaving properly,” he says. “The government isn’t not going to step in and bail out people when there’s a disaster.”

● Not Yet a Deal-breaker

Premiums are rising, but so is everything else—and insurance isn’t yet expensive enough to deter buyers, with utilities and property taxes representing a bigger share of the price of a house. Even at twice the cost, insurance would “still only account for a small proportion of asset prices,” says Danny Ismail, a researcher at analytics company Green Street. But investors in mortgage-backed securities may soon start demanding coverage for the full length of the loan. “The common denominator is that risk does not really belong to the insurance companies; it belongs to the community,” Watkins says. “The insurance market is not sufficient to tackle this problem.”

Property Owners Ignore Climate Risk Amid Insurance Meltdown

As major underwriters abandon vulnerable states, people keep moving into danger zones.

Donna LaMountain surveys damage on Pine Island Road in Matlacha, Florida, after Hurricane Ian made landfall in September 2022.

Photographer: Matias J. Ocner/Miami Herald/Getty Images

Donna LaMountain surveys damage on Pine Island Road in Matlacha, Florida, after Hurricane Ian made landfall in September 2022.

Photographer: Matias J. Ocner/Miami Herald/Getty ImagesWhen Farmers Insurance Group on July 12 said it would stop writing new homeowners policies in Florida, it became the 15th insurer in the state to take that step since early last year. Florida officials fault widespread insurance fraud for the exodus, but Farmers said it needed to “manage risk exposure” in a place where climate change threatens more natural disasters.

Florida’s slow-motion insurance meltdown is happening as new people pour into the places with the greatest risk of flooding, a pattern playing out across the US. Almost 400,000 more people moved into than out of the nation’s most flood-prone counties in 2021 and 2022, double the increase in the preceding two years, according to real estate firm Redfin Corp. Counties vulnerable to wildfires and heat have also seen more people arrive than leave.

Insurance cost is the main way the market signals risk to homeowners. Yet in California, Florida and Louisiana the markets are flashing warnings that homeowners are largely ignoring. “There are definitely disruptions in the feedback loop,” says Nancy Watkins, an actuary at Milliman Inc., an insurance consulting firm. Why aren’t property owners taking the hint?

● A Fundamental Mismatch

Mortgages last 30 years, while insurance premiums are adjusted annually. When the climate was stable, Year 1 was a pretty good predictor of Year 30. But rapid warming means the perils are constantly growing, so the premium for the first year could be wildly off 10 years later, leaving homeowners at risk of far higher premiums later on. “The entire system is predicated on climate stability,” says Spencer Glendon, founder of Probable Futures, a nonprofit dedicated to climate literacy. “I think we can expect that nexus to break down soon.”

● Demographic Danger

Many people moving to risky areas are retirees thinking about little more than warm weather and lower taxes “who accelerated their retirement plans,” says Benjamin Keys, a professor of real estate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “They haven’t experienced a weather disaster.” It doesn’t help that most people—and developers—have short memories about destruction. Or that building codes and zoning can’t keep up.

● Information Breakdown

Even when buyers seek reliable information on long-term risk, it’s hard to find, with some government maps of severe flood zones dating to the 1970s. Homeowners in those areas must purchase flood insurance to get a federally insured mortgage, but people outside the zones—or those who own their home outright—have no such requirement. First Street Foundation says some 6 million homes that should be considered at severe risk of flooding lie outside those zones. And Milliman estimates there’s $520 billion of unpriced flood loss in the housing market—a number that will only increase.

Then there’s the question of how much insurance should cost. Carly Fabian of consumer-rights group Public Citizen says buyers deserve access to average home insurance prices by ZIP code over time, which would help them assess where insurers believe risks are spiking and whether they’re paying inflated rates. But insurance companies have blocked such efforts, saying the information is proprietary. “They’ve proven unreliable narrators on climate,” Fabian says.

● The Government Backstop

In the 1960s private insurers largely pulled the plug on residential flood coverage, deeming it too risky. The federal government stepped in with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which racks up about $1.4 billion a year in losses because it can’t charge market rates. Similar state programs in California, Florida and Louisiana only insure homes that can’t get private coverage, but with insurers backing out, they’re adding customers rapidly. Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corp. is already the largest single insurer in the state.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is promising reforms that will bring NFIP premiums more in line with climate risks, but Keys is skeptical. “It’s like a dad threatening to turn the car around when the kids aren’t behaving properly,” he says. “The government isn’t not going to step in and bail out people when there’s a disaster.”

● Not Yet a Deal-breaker

Premiums are rising, but so is everything else—and insurance isn’t yet expensive enough to deter buyers, with utilities and property taxes representing a bigger share of the price of a house. Even at twice the cost, insurance would “still only account for a small proportion of asset prices,” says Danny Ismail, a researcher at analytics company Green Street. But investors in mortgage-backed securities may soon start demanding coverage for the full length of the loan. “The common denominator is that risk does not really belong to the insurance companies; it belongs to the community,” Watkins says. “The insurance market is not sufficient to tackle this problem.”

Read next: Automated Weather Insurance Could Offer Help in an Increasingly Hot World

“The common denominator is that risk does not really belong to the insurance companies; it belongs to the community,” Watkins says. “The insurance market is not sufficient to tackle this problem.”

ReplyDeletehttps://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance

ReplyDelete