Art

How Forgers and Grifters Have Conned the Art World for Generations

A popular story about

has it that, back in 1496, when he was still making a name for himself, he carved a marble sculpture of Cupid, and then artificially aged it to look like an antique. An alternate version of the story, recounted in 1550 in

’s The Lives of the Artists, posits that it was art dealer Baldassare del Milanese who presented Michelangelo’s Cupid as an antique after burying it in his vineyard. Whoever dirtied up the sculpture, the calculation was clear: an ancient sculpture would sell for more than a contemporary one. Indeed, Cardinal San Giorgio, a powerful Roman patron, fell hard for Cupid. Unfortunately for Michelangelo and del Milanese, the cardinal later found out about the scheme, returned the sculpture, and demanded a refund.

This story is startlingly similar to the acts of deceit and dupery that still roil the art world some 500 years later. Whether through outright forgery, fraud, or outrageous but alluring promises of prestige and riches, art collectors and institutions today are often as gullible as Cardinal San Giorgio. Here are nine cases spanning the last six decades that show the many ways that the art world—with its inscrutable code of ethics and undisclosed sums—is still just as opaque and susceptible to trickery as it was during the Renaissance.

Big eyes, big profits

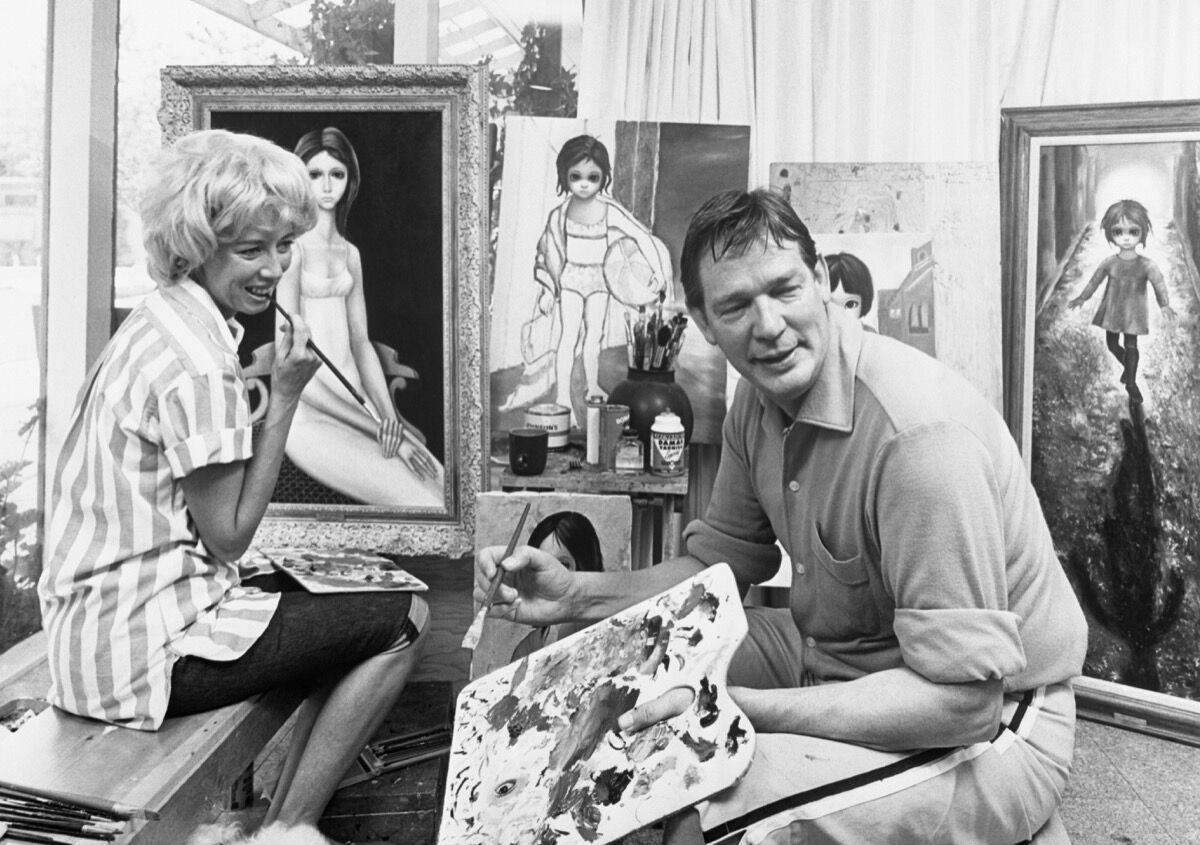

Walter and Margaret Keane. Photo by Bettmann, via Getty Images.

In the late 1950s, visitors to the hungry i, a beatnik hangout in San Francisco, could not get enough of the strangely alluring paintings of big-eyed children that a gregarious fellow named Walter Keane was selling in the front of the club. Keane claimed that the doe-eyed figures in his sentimental but technically sophisticated compositions had been inspired by the starving children he’d seen in Berlin just after World War II. “As if goaded by a kind of frantic despair, I sketched these dirty, ragged little victims of the war with their bruised, lacerated minds and bodies, their matted hair and runny noses,” he later wrote. “Here my life as a painter began in earnest.”

By the ’60s, Keane was one of the most successful commercial artists in the world, even earning praise from

. But as anyone who has seen

’s 2014 biopic Big Eyes knows, Walter wasn’t much of a painter, and instead got rich by passing off his wife Margaret Keane’s work as his own. Five years after they divorced, in 1970, Margaret pulled back the curtain on Walter’s fraud: “Give us both paint and brush and canvas and turn us loose in Union Square at high noon and we’ll see who can paint eyes.” She has gone on to have a long and successful career selling her paintings of the big-eyed figures in her own name.

The art of forgery

In most forgery schemes, the end game is money—and lots of it. For instance, the most high-profile case in recent years, the Knoedler & Co. scandal, involved counterfeited

paintings that sold for a combined $80 million. But with painter Mark Landis, identifying a motive is much murkier. Over the course of almost 30 years, he made meticulous copies of paintings in a broad range of styles that he donated to museums across the United States, sometimes even showing up dressed as a Jesuit priest to deliver the works in person. His repertoire included big names like

and

, and more obscure figures like

and Paolo Landriani.

Landis presented his forgeries as donations, often to smaller institutions that didn’t have sufficient resources to do the provenance and material research that would have revealed them to be fake. At least one museum registrar he duped caught on—the resulting art historical cat-and-mouse game is the narrative engine of the 2014 documentary Art and Craft—but because Landis never sold any of his forgeries, he didn’t break any laws, and his ploy continued for years. “Everyone has a name on a tombstone. What good is that?” Landis said in a 2012 interview. “But to have a piece of art hanging in a museum—that’s something that’ll last hundreds of years, maybe longer.”

A family affair

The Greenhalghs, a working-class family from Bolton, a town on the outskirts of Manchester, sold dozens of forgeries to museums, collectors, and other unwitting buyers over the course of 17 years. The fakes, which spanned from faux Egyptian antiquities to works by modern artists including

and

, were all made by Shaun Greenhalgh, whose elderly parents, Olive and George, helped dupe buyers into believing the works’ backstories, while his brother, George Jr., handled the money. The Greenhalghs’ victims included the Art Institute of Chicago, which wound up with a sculpture of a faun thought to be the handiwork of

; former U.S. President Bill Clinton, who bought a bust of Thomas Jefferson; and even the local Bolton Council, which purchased a supposedly 3,300-year-old Egyptian alabaster statue for £400,000 ($640,000) in 2003.

“They didn’t own a computer or live in luxury; they were living in abject poverty, a very poor lifestyle, very basic,” detective sergeant Vernon Rapley of the Metropolitan Police’s Art and Antiques Unit told BBC News. “They had a resentment of the art market and wanted to prove they could deceive it.”

After the Bolton Council sale, the Greenhalghs got more ambitious and approached the British Museum about acquiring an ancient Assyrian relief, but Shaun bungled the cuneiform script on the sculpture. The museum became suspicious and called Scotland Yard, and the unconventional family enterprise began to unravel. In the end, Shaun served nearly five years in prison for more than 40 known forgeries he created between 1989 and 2006. However, he has since claimed that many more remain undetected and in circulation to this day, including a late-15th-century drawing known as La Bella Principessa that many believe is, in fact, a

.

“The art world’s Bernie Madoff”

In 2009, six years after luxury magazine Robb Report crowned his gallery one of the world’s best, Lawrence B. Salander was indicted on charges including fraud, forgery, and grand larceny for stealing $120 million from a bank, investors (including tennis star John McEnroe), and clients of his Salander-O’Reilly Galleries (such as actor Robert De Niro). The office of the Manhattan District Attorney alleged that, over the course of 13 years, he had stolen funds and sold artworks, either wholesale or in shares, that he didn’t own or have permission to sell (some more than once) in order to fund an “extravagant lifestyle.” The duration and variety of Salander’s scams, which resulted in 100 separate charges and a prison sentence of six to 18 years in prison, earned him the nickname “the art world’s Bernie Madoff.”

A Florida pastor peddling fakes

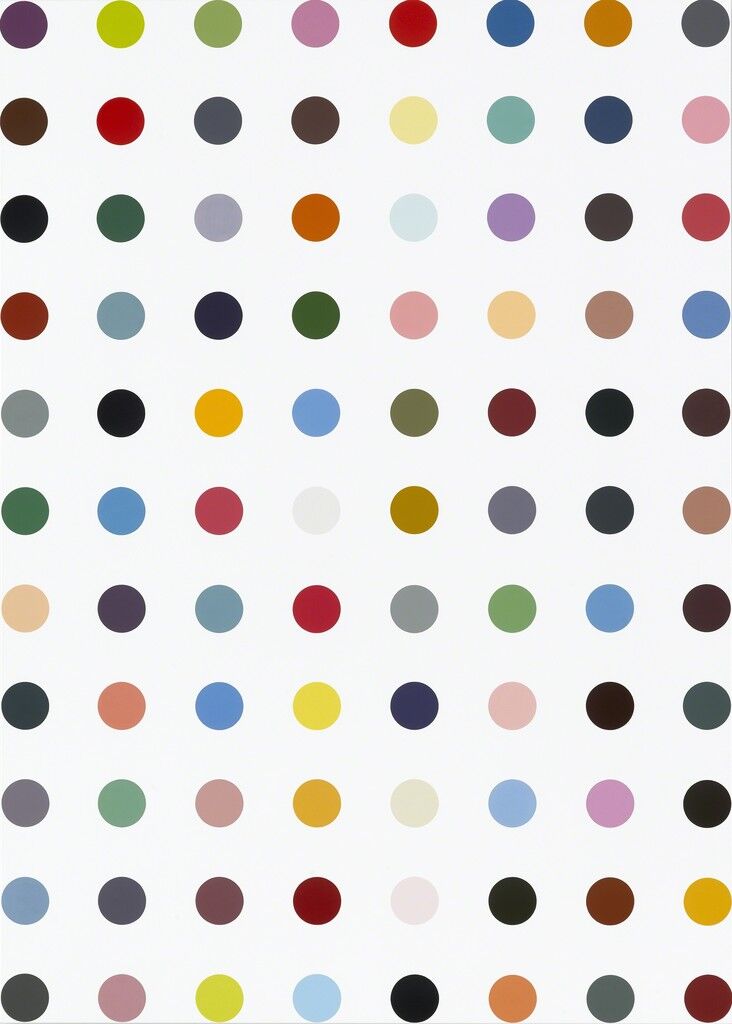

Religious vestments worked in Mark Landis’s favor when he was placing his forgeries in museum collections, but Kevin Sutherland, a pastor at the nondenominational Mosaic Miami Church, didn’t really have a prayer. Sutherland was trying to sell fake copies of works from two of

’s best-known series, the “Spot” and “Spin” paintings. In 2012, he attempted to consign one of the works to Sotheby’s, but the auction house deemed it a forgery and alerted the authorities.

Though it’s unclear whether or not Sutherland was involved in forging the works, in 2014, he was found guilty of grand larceny for knowingly attempting to sell fake artworks to an undercover cop. He was sentenced to six months in prison and five years’ probation. After Sutherland was convicted, Manhattan district attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr. commented that “because the art industry is largely unregulated, it is particularly important to hold accountable those who fraudulently deal artwork.”

Sticky-fingered assistant

James Meyer worked in the studio of renowned American artist

for over 25 years, helping to catalogue new works and get rid of any that Johns deemed unsuccessful. But on at least three occasions, Meyer kept the unfinished and discarded works by his longtime employer and friend. After drawing up certificates of authenticity and making fake inventory numbers for the stolen pieces, Meyer sold 37 of the works through New York’s Dorfman+ gallery, insisting that buyers couldn’t re-sell, lend, or exhibit them publicly for eight years.

According to prosecutors, the sales of the stolen works eventually totaled about $10 million, of which Meyer kept $4 million. From his privileged position in Johns’s studio, Meyer was in the perfect situation to not only deceive the artist, but also to present himself as a trustworthy agent when selling the pieces to dealers. In 2013, he was indicted and ordered to forfeit the money from the sales, plus pay a total of $13.5 million in restitution to Johns and the buyers of the stolen works. Finally, in 2015, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

A purveyor of purported Pollocks

Sometimes, when an eBay find seems too good to be true, it is. But the people who bought paintings advertised as authentic

from a Hamptons-based seller between 2005 and 2012 were blinded by the thrill of discovery. They may also have been enticed by the story spun by the seller, John D. Re, who claimed that he’d found the trove of Pollocks while cleaning out the East Hampton basement of an antiques restorer’s widow. Re ultimately sold more than 60 fake Pollocks through eBay and directly to private collectors, making nearly $1.9 million in the process.

However, after multiple collectors tried to have the works authenticated to no avail—the International Foundation for Art Research noted that they were “remarkably, and disturbingly, analogous to each other in palette, composition, and overall execution, much more similar, in fact, than any of Pollock’s authentic works are to each other”—the FBI got involved. Re was arrested in 2014, and the following year, he was sentenced to five years in prison.

The fall of the manuscript king

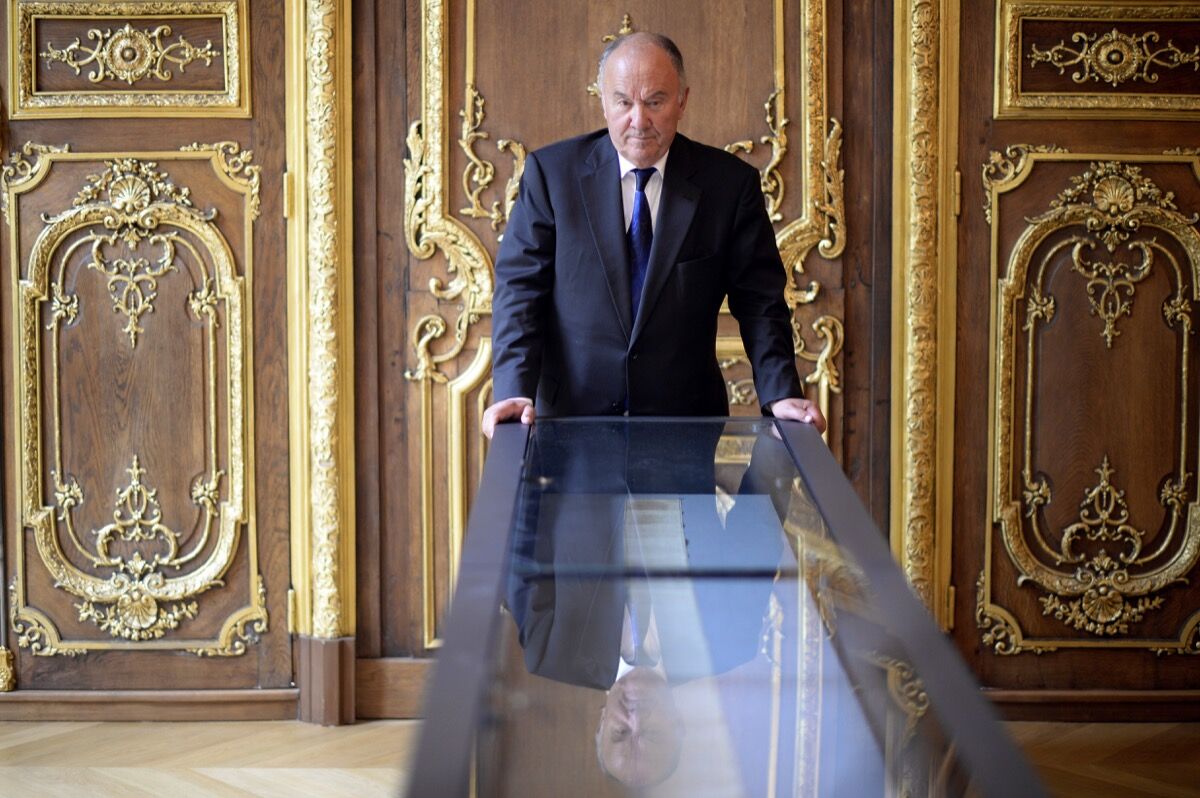

Gerard Lheritier with Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom, 2014. Photo by Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images.

Though his passion for rare letters and manuscripts earned him the title “king of manuscripts,” French collector and businessman Gérard Lhéritier might more accurately have been nicknamed the “pharaoh of manuscripts,” because his investment company Aristophil is suspected of being the centerpiece of a nearly $1 billion pyramid scheme.

Lhéritier founded Aristophil in 1990, and soon after, he began to amass one of the world’s richest collections of rare books, ancient manuscripts, historic letters, and important documents. Highlights of his collection included

’s original

manifesto; the scroll on which the Marquis de Sade wrote 120 Days of Sodom; Napoleon’s marriage and divorce contracts; and Louis XVI’s final testament. He then offered collectors the opportunity to invest in the 135,000-piece collection, promising annual returns of 8 percent. Ultimately, 18,000 clients opted in to the tune of a whopping €850 million ($990 million).

In 2014, as more and more of those clients inquired about their promised returns, Aristophil’s accounts were frozen, and a state prosecutor in Paris investigated the company; the following year, Lhéritier was arrested. In December 2017, the first auction of items seized from Aristophil’s collection brought in just €3 million ($3.5 million), a drop in the bucket compared to the nearly hundreds of millions that may be needed to repay Lhéritier’s investors.

The mother-and-son team

In 2015, Wall Street trader and prominent collector Andrew J. Hall—whose 5,000-piece collection includes a semi-permanent installation of

paintings at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, and a rotating program of exhibitions at a foundation in rural Vermont and a castle in Germany—began organizing an exhibition of one of his favorite artists,

. But in doing so, he discovered that 24 of his Golubs were fake.

Hall had purchased eight of the paintings through Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and online auction site Artnet. After discovering their source—Lorettann and Nikolas Gascard, a New Hampshire art history professor and her son—Hall approached them directly to buy the rest. In the end, Hall paid $676,250 for 24 paintings, but when he began planning to exhibit the works, the Nancy Spero and Leon A. Golub Foundation for the Arts—which represents the estates of Golub and his wife,

—flagged them as “likely forgeries.”

In 2016, Hall filed a lawsuit against the Gascards, and late last month, a judge cleared the way for it to go to trial. Whether the Gascards knew the works were fake or were themselves victims of a scammer, the forgeries were sufficiently convincing to pass muster with auction house specialists and a major collector, illustrating just how easy it can be to game the art world’s opaque systems.

Benjamin Sutton is Artsy’s Lead Editor, Art Market and News.

No comments:

Post a Comment