Art

Three Ways Art History Needs to Change in 2019

The field of art history is partial, contentious, and constantly up for debate. The extent to which the discipline has an actual, noticeable effect on culture and everyday life is constantly questioned. But naysayers perilously undermine the loftier ambitions and rewards of engaging with art history in academic, professional, and cultural spheres.

Okay, so this branch of the humanities might not be the most practical subject. Even eminent art historian Erwin Panofsky conceded to this point in his influential 1940 essay “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” questioning why we bother to engage in such “impractical investigations” at all. Why, he asked, “should we be interested in the past?” His answer is simple: “Because we are interested in reality.”

As one of the most naturally interdisciplinary subjects, art history provides a vital toolkit for us to interpret and understand our world. The way we go about practicing it needs a serious retooling, precisely because art history offers such a nuanced lens to examine our society. A single artwork, Panofsky wrote, encompasses “the basic attitude of a nation, a period, a class, a religious or philosophical persuasion.” History is a living thing; it requires constant tending, updating, and reappraisal to reflect change, our evolving attitudes and circumstances. Below are three steps to attain newfound levels of parity and openness in all art-historical arenas in 2019.

Diversify the next generation of art historians

Mainstream history is an exercise in exclusivity, a story that is “written by the victors,” as the saying goes. It’s also a highly subjective discipline, deeply affected by bias. Howard Zinn saliently explored this issue in A People’s History of the United States (1980), a chronicle of the oft-neglected plights of Native Americans, African-Americans, and women, among other oppressed and marginalized groups. With his “alternative” textbook, Zinn perfectly exemplifies that any change to conventional narratives must begin with the historian.

Art history is no exception; similar forms of exclusion manifest in classrooms, museums, and publications. It’s not news that major barriers to access—pricey master’s degrees, unpaid internships, and rampant nepotism chief among them—have kept the art world disproportionately white, male, and upper middle class. Recent statistics gathered by Data USA found that among those with art history, criticism, and conservation degrees, both at the undergraduate and graduate level, a staggering 70% are white. (Hispanic is next at 11%, Asian at 5.5%, black at 3.1%, and Native squeaks in at 0.2%.)

Compare these numbers with a 2015 study by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It revealed that although there’s a “significant movement toward gender equality in art museums,” with women comprising about 60% of museum staffs in leadership, curatorial, conservation, and educational positions (a relatively low count, considering that women constitute 85.1% of all art history degree-holders), there’s “no such pipeline toward leadership among staff from historically underrepresented minorities.” The study found only 4% of workers in those roles to be African-American, and 3% Hispanic. (For context, 13.4% of the U.S. population identifies as African-American or black, and 18.1% as Hispanic or Latinx.)

The voices of people of color are pivotal when it comes to redressing these oversights and omissions. Last year, art historian Denise Murrell, who is black, offered a compelling correction to the canon. Her “investigations into the understudied black muses of art history,” as Tess Thackara recently wrotefor Artsy, became the subject of her Ph.D. thesis and an exhibition, “Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today,” on view at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery (an expanded version of the show will travel to the Musée d’Orsay this March).

The topic unfolded from a long-running list Murrell had been keeping of “instances of black” in Western art. She was particularly struck by the black maid prominently featured in

’s provocative Olympia (1863)—and the fact that little to nothing had ever been written about her. The exhibition, along with the scholarly catalogue that accompanies it, not only fills major gaps in our understanding of modern art and its players, but also reflects on latent bias in the cultural sphere. This is the potential speaking-truth-to-power that results from putting resources into diversifying the next generation of art historians.

This past September, in a major effort to increase diversity in the field, the Walton Family Foundation awarded Spelman College a $5.4 million grant to establish the Atlanta University Center Collective for the Study of Art History and Curatorial Studies. This fall, the historically black women’s college will offer its first major in art history, with a minor in curatorial studies. The center aims to become one of the country’s foremost incubators of African-American art-world professionals.

In the absence of such dedicated institutions, networks of support have largely been built by impassioned individuals. Thelma Golden stands as one prominent example. During her tenure as director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, she has championed many artists and curators of color. Her acolytes—including the Museum of Modern Art’s Thomas J. Lax, and Rujeko Hockley, co-curator of the 2019 Whitney Biennial—continue her legacy, showing at or working for some of the most influential museums in the world. “Many people of color in the art museum field, myself included,” Golden said in a statement after the grant was announced, “can trace much of our success to mentorship and professional development opportunities provided early in our careers.” Such networks and guiding individuals are key, but without more entrenched institutional support—beginning with academic institutions—the field may very well remain homogenous, a sure path to obsolescence.

Tell a more inclusive story of art

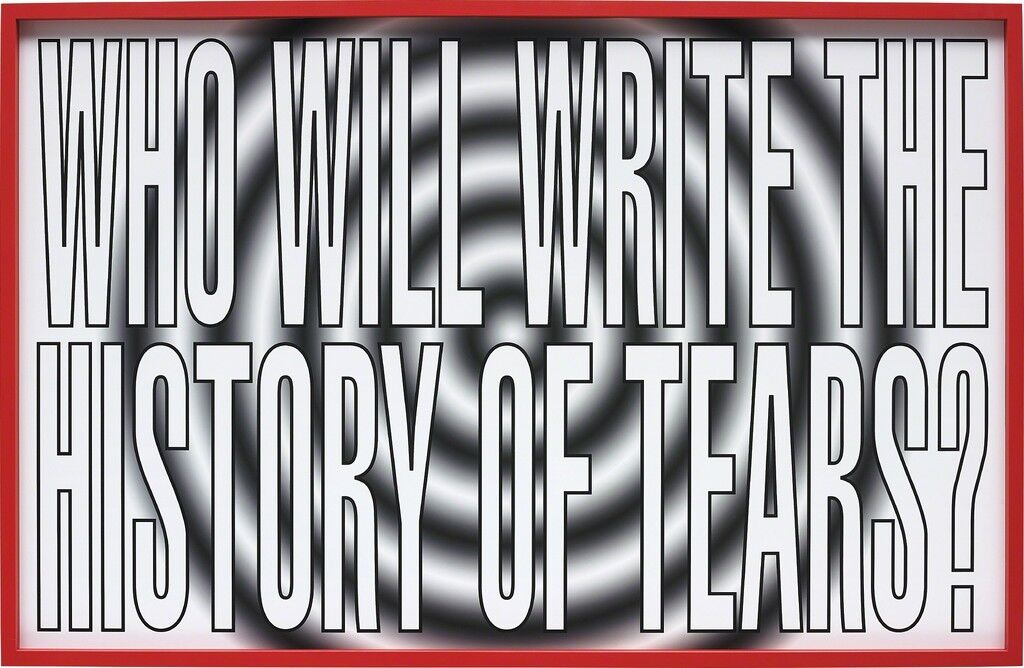

Barbara Kruger

Phillips

No matter where art history is played out—in universities, museums, or on the pages of magazines—its practitioners must adapt to the times or risk stagnation. Art history is by nature interdisciplinary; art is contextualized by politics, philosophy, ethics, literature, religion, and economics. Art history programs should therefore encourage students to study these subjects in order to have a fuller understanding of the complex systems encapsulated by an artwork. The general expunction of money or the market from art history, for instance, is more than outdated, it’s backwards; both are integral to understanding the production and circulation of art over the last five thousand years.

Several programs have taken strides to expand the academic approach to the discipline. The Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History, for example—founded at the University of Texas at Dallas in 2014, with additional headquarters at the Dallas Museum of Art—is dedicated to an agenda of cross-pollination between the visual arts, sciences, and technology. To that end, graduate research initiatives include courses on art and medicine, a data-driven approach to interpreting art history, and partnerships with international institutions that examine global exchanges in art.

Research and exhibitions that highlight points of cross-cultural connections to show multiple perspectives—speaking to the relative values of art to illustrate class disparity, or repositioning the traditional “center” of art-historical narratives to focus on non-Western contributions—all further thecall to “decolonize” the art world. One high-profile success story last year occurred when Charles and Valerie Diker gifted their collection of Native American art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stipulating that it had to be shown in the museum’s American wing and integrated into the broader story of American art, rather than ghettoized in its own “Native” section. It felt like a game-changing victory to view these works in pride of place among the familiar trophies by white male heroes of 20th-century art.

The need to remedy the lack of visibility on marginalized artists has inspired other art historian–fueled initiatives. A crop of new databases—such as the Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions; Clara, from the National Museum of Women in the Arts; and the Canadian Women Artists History Initiative, run by Concordia University—strive to write women into art history by conducting original scholarship and making it available online.

The public is hungry for the excitement of an unknown discovery or the drama and gore of historical truth, and the many recent calls to hold institutions accountable for their role in representing culture is a rousing affirmation that art—and its temples—is indeed politically engaged. The popularity of guided museum tours that offer alternatives to mainstream art histories further proves this fact (see the “Badass Bitches” tour by Museum Hack, or Alice Procter’s anti-colonialist “Uncomfortable Art Tours”). Some museums are starting to wise up to this shift in public engagement. Tate Britain, to cite one example, now offers “A Queer Walk Through of British Art,” a tour of “queer responses” to its collection in the form of supplementary wall labels attached to works in their permanent galleries.

Break down the divisions between “high” and “low” art

The commanding art critic Clement Greenberg laid out the necessity of the art world’s modernist project in his now-canonical 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” Forward-thinking art, he insisted, combats the docile complacency of a general public that is easily manipulated by consumerist forces and fascist regimes, who propagandize campy, mass-produced imagery.

The growing Nazi threat in Europe added special urgency to the Jewish-American critic’s writing, but Greenberg’s essay, while influential, had perhaps unintended consequences. In it, he defined an unbridgeable line between the avant-garde and popular forms of art considered outside the official art world. The stark moral distinction between the two was clear: the former fights fascism, the latter propels it. Such high-minded divisions between so-called “high” and “low” art have been maintained by institutional gatekeepers for centuries, but if the art world is to become a more inclusive place for heterogeneous voices and styles, we must reevaluate the self-imposed boundaries it operates under.

In their new book Aesthetics of the Margins / The Margins of Aesthetics: Wild Art Explained, co-authors David Carrier and Joachim Pissarro trace a history of the institutionalization of taste, rejecting the binary of “serious” art shown in galleries and museums and what they call “wild” art, a wide range of creative enterprises—from street art to fashion to tattoos—that exist in a multiplicity of art worlds operating outside the system. It’s crucial to recognize that the hierarchical division of art forms—traditionally prioritizing oil painting and sculpture over textile arts and other “domestic” crafts—has abetted the exclusion of women, people of color, and artisans of the lower classes.

The first step to erasing these boundaries, Carrier told Artsy, is to recognize that the differences between them are, in fact, largely arbitrary, borne of any system’s need to police its borders. Carrier cited a literal example of the divide: “When you go to MoMA or the Met,” he said, “you see all of these people right outside the doors of the museums selling street art, paintings, and so forth. They’re so close, yet so far; they’re never going to be admitted into the art world.”

In our postmodern age, there might not be easily definable criteria for what constitutes high art versus kitsch, but Carrier cites irony as a major determining factor.

, he offered, was “fabulously successful; his paintings were in 1 in every 20 American homes.” Yet he was never taken seriously by the establishment. Carrier senses that this rejection was “because he was not ironical. He did

scenes that have a sweet view of the world. That’s not accepted in the art world.”

Institutions have, little by little, become more accepting of various art forms over the last few decades. Major exhibitions of fashion and street art—like the Met’s “Heavenly Bodies,” which shattered the museum’s attendance record last year—have drawn thousands of visitors, along with the snooty disdain of some critics. But Carrier is still hopeful. “Anything can make its way [into the art world],” he posited, “but you can’t have everything coming in at once.”

It seems inevitable that major museums will only continue to expand their programming of commercially appealing exhibitions on “wild art” topics like popular music, street fashion, video games, or graffiti. Now is as fine a time as any for university art history programs to similarly seek out ways to take these subjects seriously, and incorporate them into their own curricula. While there are some interdisciplinary programs like this already in existence—mostly under the guises of “Cultural” or “Visual Studies,” the latter offered by the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts—more traditional art history courses could easily adopt this same spirit.

Still, as individuals, we can reap the simple but profound benefits of such openness to aesthetic experience. Researching the book with Pissarro, Carrier said, “opened our eyes to see lots of things that maybe we wouldn’t have looked at otherwise. That’s what we’re advocating. Open your eyes. There’s a lot to look at.”

Julia Wolkoff is Artsy’s Art History Editor.

No comments:

Post a Comment