Creativity

Why Artists Who Dabble in Other Professions Find Success

We love stories about people who triumph despite the odds. The underdog genre—as old as David and Goliath—is a Hollywood favorite. Films from Miracle (2004) to Ali (2001) focus on sporting events where teams or individuals pull off upsets and become national heroes. The theme extends to creative endeavors as well. A famous literary anecdote recounts that Stephen King faced 30 rejections from publishers for his first novel, Carrie(1974), before Doubleday bought it.

The principle holds true in the visual arts, too. Take for example beloved

, who was born into poverty in the Jim Crow era and got his start carving tombstones for his sister’s deceased children. And

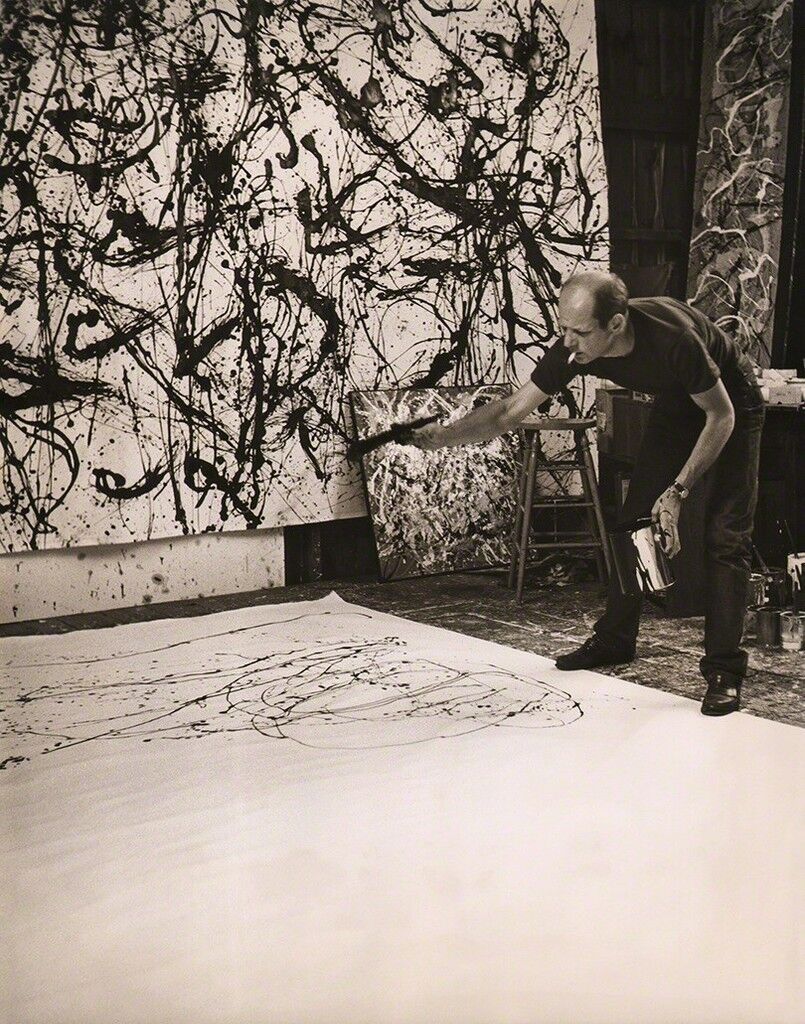

, who was one of the worst draftsmen at the Art Students League before becoming one of the 20th century’s most important painters.

Pollock’s story is included in David Epstein’s new book Range (2019), which is filled with miniature biographies of artists and public figures, from tennis champion Roger Federer to former Girl Scouts CEO Frances Hesselbein. Despite their disparate endeavors, the subjects’ tales all feature meandering—or rather, ranging—paths. Epstein argues that these trajectories are integral to success in any field. He suggests that artists should be generalists, unafraid of trying different disciplines, before focusing on their craft.

Epstein’s book responds to the idea that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert at anything, a principle Malcolm Gladwell popularized in his 2008 book Outliers. Epstein notes that evidence for the theory extrapolates from data related to golf—a game which rewards repetitive practice. “That’s not how artistic creation works,” Epstein explained recently. “You’re trying to do something new to you, and in some cases new to anyone. One of the sources of power for doing things like that is having really broad experiences.” That often requires trying, and failing, at a number of different activities.

was a stockbroker who was forced to find a new career path after the market crashed in 1882.

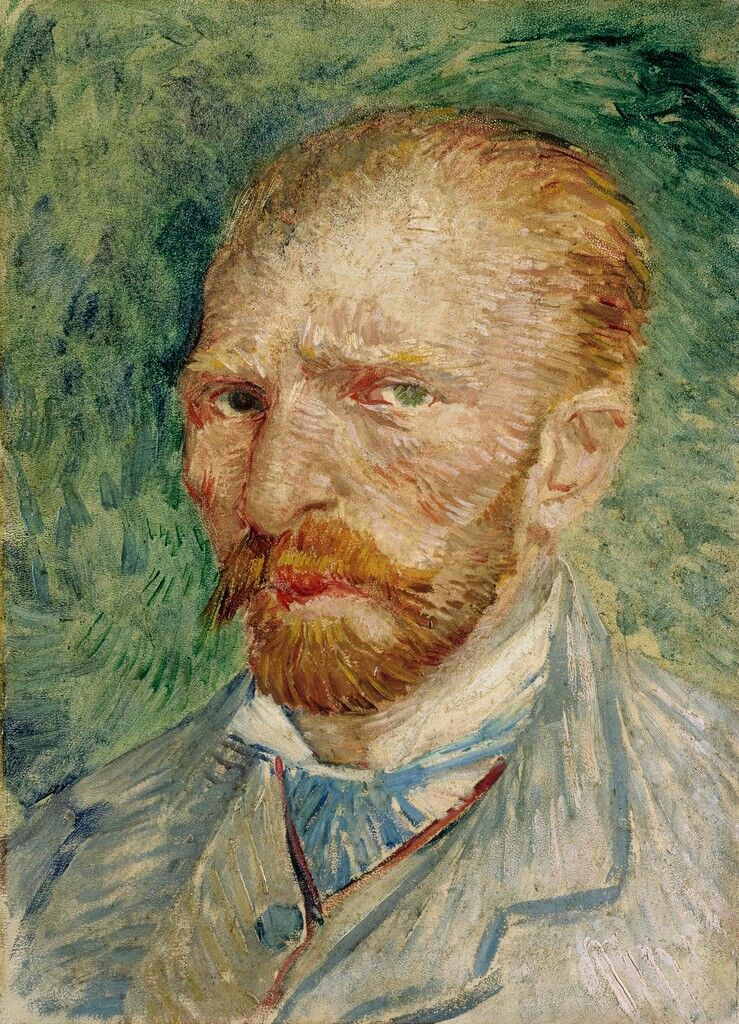

failed as an art dealer before he painted some of art history’s best-loved canvases.

never formally learned to draw, then became one of the United States’ most famous—and expensive—artists.

famously worked in finance before becoming today’s most prominent living American artist.

had already studied modern dance and worked as a labor organizer before she embarked on her own formidable art career.

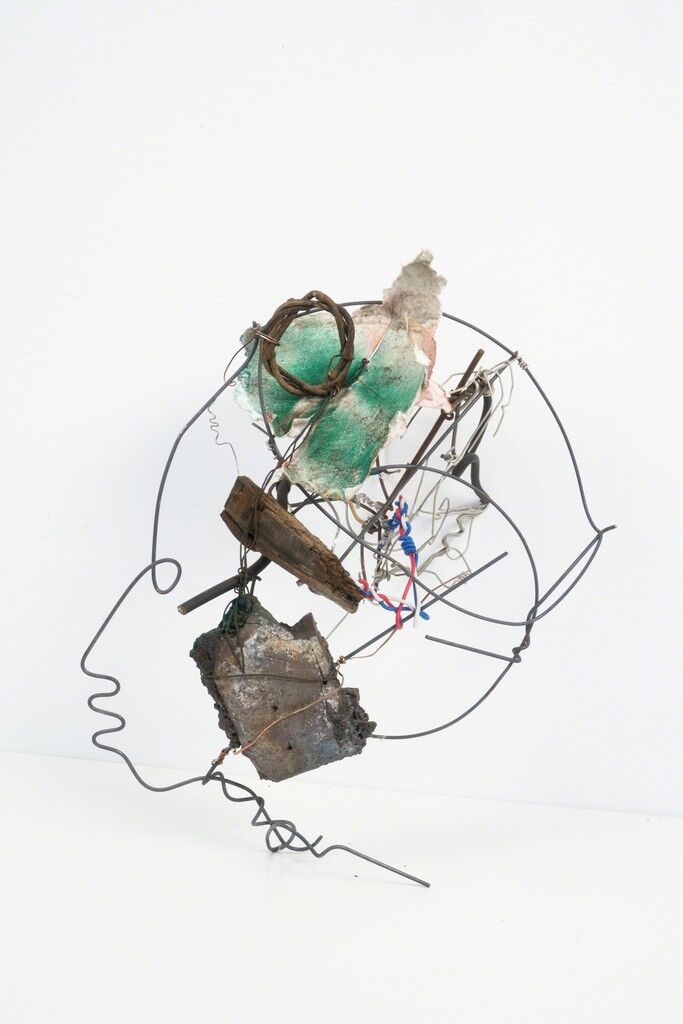

All of these artists, in their own way, demonstrated one key attribute of success: “match quality.” The economics term, Epstein writes, is used to “describe the degree of fit between the work someone does and who they are—their abilities and proclivities.” What artists such as Pollock and Basquiat lacked in traditional drawing skills, they made up for in commitment to their work and engagement in art. They also tried out other art forms before devoting themselves to their signature painting styles: Pollock made murals, drew, and worked in a figurative vein, while Basquiat began in graffiti. Sampling alternate modes proved crucial to their careers and to their eventual, groundbreaking canvases. Weems has tied her dance background to the role of the body throughout her photography.

Epstein doesn’t limit his discussion of artists to such giants of 19th and 20th culture. In a chapter about lateral thinking, he writes about comic book artists. He cites a 2006 study by Alva Taylor and Henrich Greve which examined comic books’ commercial values. The pair hypothesized that artists who produced more comic books and had more years of field experience would create the highest-valued products. Instead, what mattered was how many genres (crime, fantasy, sci-fi, etc.) an artist had worked in. “Where length of experience did not differentiate creators, breadth of experience did,” Epstein writes. “Broad genre experience made creators better on average and more likely to innovate.”

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Head, 1982 -2001

While surgeons and airline crews benefit from repetitive practice—the smoothest operations and flights are often the result of specialized expertise and training—screenwriters, authors, and artists require a range of material to create innovative new work. Jordan Peele, Epstein suggests, drew on his expertise in comedic timing in order to create the hit horror film Get Out (2017). Neil Gaiman’s writings on art, and his forays into children’s literature, have perhaps enhanced the psychological complexity of his adult novels. Instead of dismissing their diverse paths, said Epstein, artists should learn to tell better stories about their lives, “explaining their zigzags as part of one holistic narrative.”

Epstein himself became enthralled with such tales during the research for his book. In fact, he started collecting art after learning about his subjects’ intriguing life stories. A

print now hangs above his child’s crib. Outsider artists, and Lonnie Holley in particular, became favorites. Range, for them, was a product of necessity. They often had no access to the traditional paths, such as MFA programs, towards an art career.

During his research, Epstein began thinking more critically about such artists’ backgrounds. Like jazz musicians, he said, these artists “had to create their own forms, and some of those turned out to be paradigm shifting.” There’s nothing wrong with formal training, he continued, but “we stand to miss a wealth of talent and creativity if our pipeline is so narrow that it erects tremendous barriers for people with nontraditional backgrounds or whose styles evolve slowly.” That would be an awful waste—their intriguing stories, as much as their artwork itself, enriches contemporary culture.

Alina Cohen is a Staff Writer at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment