Art World

Here Are the 10 Absolute Best Works of Art We Saw Around the World in 2018

From John Akomfrah's gut-wrenching films at the New Museum to Tschabalala Self's homemade bodega in Shanghai, here's the art we'll remember most.

BEST ART OF 2018

ART OF 2018

There’s a lot of art out there. A lot of it is notable in the moment, but doesn’t necessarily stick in the mind. Then there’s that show—or that individual work—you can’t forget. Below, our editors pick the most memorable, exciting, and enchanting art they saw this year.

Bruce Nauman‘s Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (2015–16)

in “Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts” at the Museum of Modern Art

Bruce Nauman, still from the seven-channel video Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (2015-16). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York

—Andrew Goldstein

Marianna Simnett, The Udder (2014)

in “Marianna Simnett: Blood In My Milk” at the New Museum

Still from Marianna Simnett’s The Udder (2014).

—Julia Halperin

John Akomfrah’s The Unfinished Conversation (2012)

in “John Akomfrah: Signs of Empire” at the New Museum

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation (2012). Courtesy of Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

—Pac Pobric

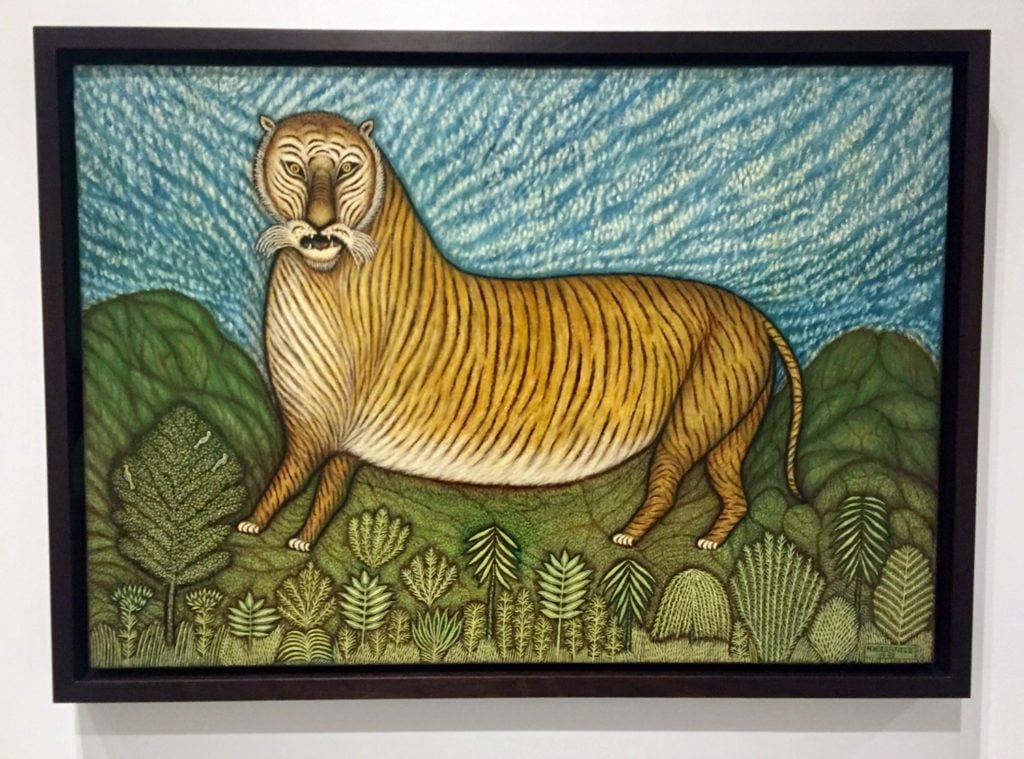

Morris Hirshfield’s Tiger (1940)

in “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Morris Hirshfield, Tiger (1940) in “Outliers and Vanguard Art” at the National Gallery of Art. Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

—Ben Davis

Tschabalala Self’s Bodega Runat the Yuz Museum in Shanghai

—Eileen Kinsella

Paola Pivi’s World Record (2018)

in “Paola Pivi: Art With a View” at the Bass Museum, Miami Beach

Paolo Pivi, World Record in “Paola Pivi: Art With a View” at the Bass, Miami Beach. Visitors enjoying the installation include Creative Time director Justine Ludwig, third from right, and the artist herself, second from left. Photo by Attilio Maranzano, courtesy the artist and the Bass, Miami Beach.

Little did I know that Pivi herself was among those lounging on the comfy installation, which I quickly likened to the world’s largest pillow fort. She envisioned the work as a protected space, a floor and ceiling of mattresses offering “padded white peace,” as per the exhibition label—a place where adults might play like children.

What I found was an immediate sense of relief, the stress of the day melting off my shoulders as I collapsed against the cushions. The sound was oddly deadened as I spoke to the other people sprawled out on the mattresses. The soft, springy surface seemed to stretch on forever, creating a world without responsibility or consequences.

I wanted to stay there forever, enveloped in the sense of joy and community Pivi had created, safe from the chaos of the fair and deadlines. Sadly, reality came calling all too soon, but those five minutes of bliss made my week, and maybe even my year.

—Sarah Cascone

Giotto’s Lamentationat the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy

Giotto’s Lamentation of Christ (ca. 1305) at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

—Rachel Corbett

Mario Pfeifer’s Again / noch einmal (2018)

at the Berlin Biennial

Video still of Mario Pfeifer’s Again / Noch einmal (2018). Courtesy of Mario Pfeifer, KOW, Berlin, copyright 2018 VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

—Kate Brown

Simon Fujiwara’s Empathy I (2018)

in “Revolution” at Lafayette Anticipation, Paris

Exhibition view of Simon Fujiwara, Empathy I (2018). Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2018. Photo © Andrea Rossetti.

The actual experience is, of course, more akin to a Disneyland 4D film than a rollercoaster, but my anxiety primed me for the emotional onslaught to come. Through Fujiwara’s video collage of found footage you’re thrust into the first-person perspective in a variety of scenarios and emotional states, dancing at a wedding, jolting over the desert in a four-wheeler, splashing into the ocean on the edge of a raft, the different scenarios flickering out faster than your brain can keep up. It’s over in four minutes, after which you feel like you’ve lived a thousand lives. If you’re a hypersensitive person like me you’ll probably be in tears.

—Naomi Rea

John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea (2015)

in “John Akomfrah: Signs of Empire” at the New Museum

After viewing Vertigo Sea, the gravitational center of the pioneering British media artist John Akomfrah’s exhibition, I left the gallery reeling like a sailor who had just survived a shipwreck. The monumental three-channel video installation manages to take something normal humans are incapable of processing—the relentless, centuries-long campaign by the most powerful of our species to pillage everything outside of themselves for utility, profit, and ego—and renders it visible and visceral.

True to its title, Akomfrah frames most of Vertigo Sea around bodies of water. And while its arc turns on the theme of colonization, the work also surfaces man’s exploitation of plants and animals. It calls out the direct link between, say, sailing to Alaska to shoot polar bears and sailing to Africa to enslave other humans (who can then simply be thrown over the bow of a ship when their perceived usefulness has expired).

At the same time, its images are consistently arresting—a mix of high-production-value filmic setups, top-tier nature cinematography, and brutal found footage. The only thing I can think to compare it to is a nightmare I once had about watching a giant snake engulf me from the toes up: a vision simultaneously too terrible and too remarkable to turn away from until it was over.

—Tim Schneider

HONORABLE MENTIONS

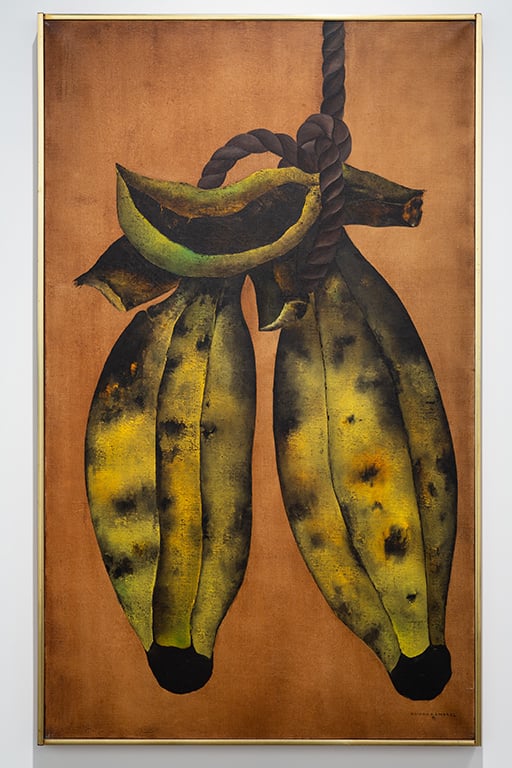

Antonio Henrique Amaral’s As Duas Suspensas (1972)

in “AI-5 50 Years: Still Hasn’t Ended Yet” at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo

In Sao Paolo for the 2018 Bienal, I had the good fortune of passing through this show, curated by Paulo Miyada. A half century after the infamous “Fifth Institutional Directive” of 1968, which dramatically intensified repression under the Brazilian dictatorship, the show looked at how artists processed the country’s descent into darkness. The subject matter was, of course, sadly freshly topical in the shadow of the ascent of the dictatorship-loving Jair Bolsonaro, and Amaral’s work from his most well-known series of bruised bananas says everything plainly through the elemental devices of its brooding tones and swollen and strangled forms.

—Ben Davis

Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit (1971)in “Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016” at the Museum of Modern Art

Adrian Piper, Food for the Spirit #8 (1971, reprinted 1997). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin. Photography by Jonathan Muzikar

Then you recall that Kant’s key philosophical term in the First Critique was “antinomy,” “a contradiction between two beliefs or conclusions that are in themselves reasonable,” much the way you feel that the two parts of Food for the Soul run enigmatically parallel here as evidence of her experience, the purely cerebral, the viscerally corporeal—both valid.

And then, after another moment of reflection, this sense of an artwork divided also falls away, as the two sides blur back together: You realize that Piper’s handwriting in the book is evidence of her body present in the process of thinking, while her photo self-portraits, with their disciplined progression and variation, are as vivid an image as any of a consciousness trying to shape its self-awareness. A work that both predicts the contemporary interest in self-fashioning and self-presentation and complicates its premises in advance.

—Ben Davis

INNER COURSE, THE AGONY OF IT ALL (2018)at the Bunker in West Palm Beach and at Smack Mellon in Brooklyn

If you haven’t made it to Beth Rudin DeWoody’s private West Palm Beach art space the Bunker yet, you should know that it is every bit as spectacular as you’ve heard. Welcoming visitors during the first-annual New Wave Art Wknd, DeWoody and her curator Laura Dvorkin also arranged to hold a special performance by INNER COURSE, a project from Rya Kleinpeter and Tora López.

THE AGONY OF IT ALL, originally staged at Brooklyn’s Smack Mellon over the summer, sees Kleinpeter and López, outfitted as retro housewives a lá Lucille Ball, in twin beds. Surrounding them is a mountain of outrageously sexist books about women—some well-meaning, others unabashedly misogynistic. They sip wine to console themselves, reading aloud until they break into tears, blowing their noses theatrically and offering visitor tissues.

The piece was hilarious, but also heartbreaking. At first, you think, how ridiculous these books are. Then, you remember that someone took the trouble to write each of them—and some quite recently. These words are a reflection of the attitudes of the patriarchy, still deeply ingrained in our society even in the age of #MeToo. If you or someone you love doubts the continued relevance for feminism, think again.

—Sarah Cascone

Tauba Auerbach, Flow Separation (2018)

from the Public Art Fund, New York

Tauba Auerbach’s Flow Separation, commissioned by the Public Art Fund, succeeded on so many levels. For one thing, it was a sheer visual spectacle: a large ship painted in spectacular swirls of white and red, a design created through the technique of marbling. It also engaged with its environment, bringing New Yorkers who rarely have reason to recall Manhattan’s status as an island out on the water, exposing them at once to nature and the city’s unparalleled skyline. And it was a lesson in history, inspired by the dazzle ships of World War I, a counterintuitive form of bold camouflage aimed at confusing the enemy, invented by British painter Norman Wilkinson.

If you didn’t get to go for a ride on the John J. Harvey, the historic fire ship brought back into service for the project, then you missed a truly special experience. But the boat is docked at Hudson River Park’s Pier 66a through May 12, 2019, so you can still see Auerbach’s work of art for the whole family—something experiential yet beautiful, accessible at first glance and yet layered with meaning. Best of all, it was free and open to the public.

—Sarah Cascone

Sol LeWitt‘s Complex Form #34 (1990)

in “Between the Lines” at the Fondazione Carriero, Milan

Sol LeWitt, Complex Form #34 (1990). Photo by Agostino Osio. Installation view at Sol LeWitt. Between the Lines, Fondazione Carriero, Milan (2017-2018). Courtesy Fondazione Carriero, Milan.

—Naomi Rea

Eugene Delacroix’s The Murder of the Bishop of Liège in “Delacroix” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Eugene Delacroix, The Murder of the Bishop of Liège (1829). Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

—Eileen Kinsella

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Share

No comments:

Post a Comment