Visual Culture

How Women Artists in Victorian England Pushed Photography Forward

Lady Clementina Hawarden, The Return From the Ball, Study, 1900. © Historical Picture Archive/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

Long marginalized from the mainstream art world, female artists have often found their voices in new mediums.

, for example, gave the likes of

, Diane Torr, and

room to make a new form of art with their bodies, unencumbered by the male centrism of mediums such as painting and sculpture. When

began documenting their performances, they helped spur the development of video art.

Earlier, in the 19th century, when photography was considered outside the remit of fine art, women found fertile ground for making their mark in the new medium. “Unlike the gun, the racquet and the oar, the camera offers a field where women can compete with men upon equal terms,” wrote Clarence Moore, rather patronizingly, in an 1893 Cosmopolitan article. Photography didn’t require academic training; in theory, it could be picked up from popular manuals. Overlooked as painters for centuries, women found an art form they could shape—and the result was several bodies of work that feel light-years ahead of photography produced by many men of the same era.

For example, Lady Clementina Hawarden (1822–1865), confined to a place in the home like so many women of her time, turned this limited purview into a strength, capturing intimate images of her domestic life. Hawarden was married to one of the wealthiest men in Britain and raised eight children, whom she portrayed in hundreds of photographs. When she died, one of Hawarden’s descendents left 775 of her pictures to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, most of which feature her children, as well as the same starry wallpaper and a mahogany desk inlaid with mother-of-pearl. These undated, unnamed “studies” convey a world of leisure and offer candid psychological portraits of Hawarden’s teenaged offspring.

Lady Clementina Hawarden, Woman at a Mirror, 1900. © Historical Picture Archive/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

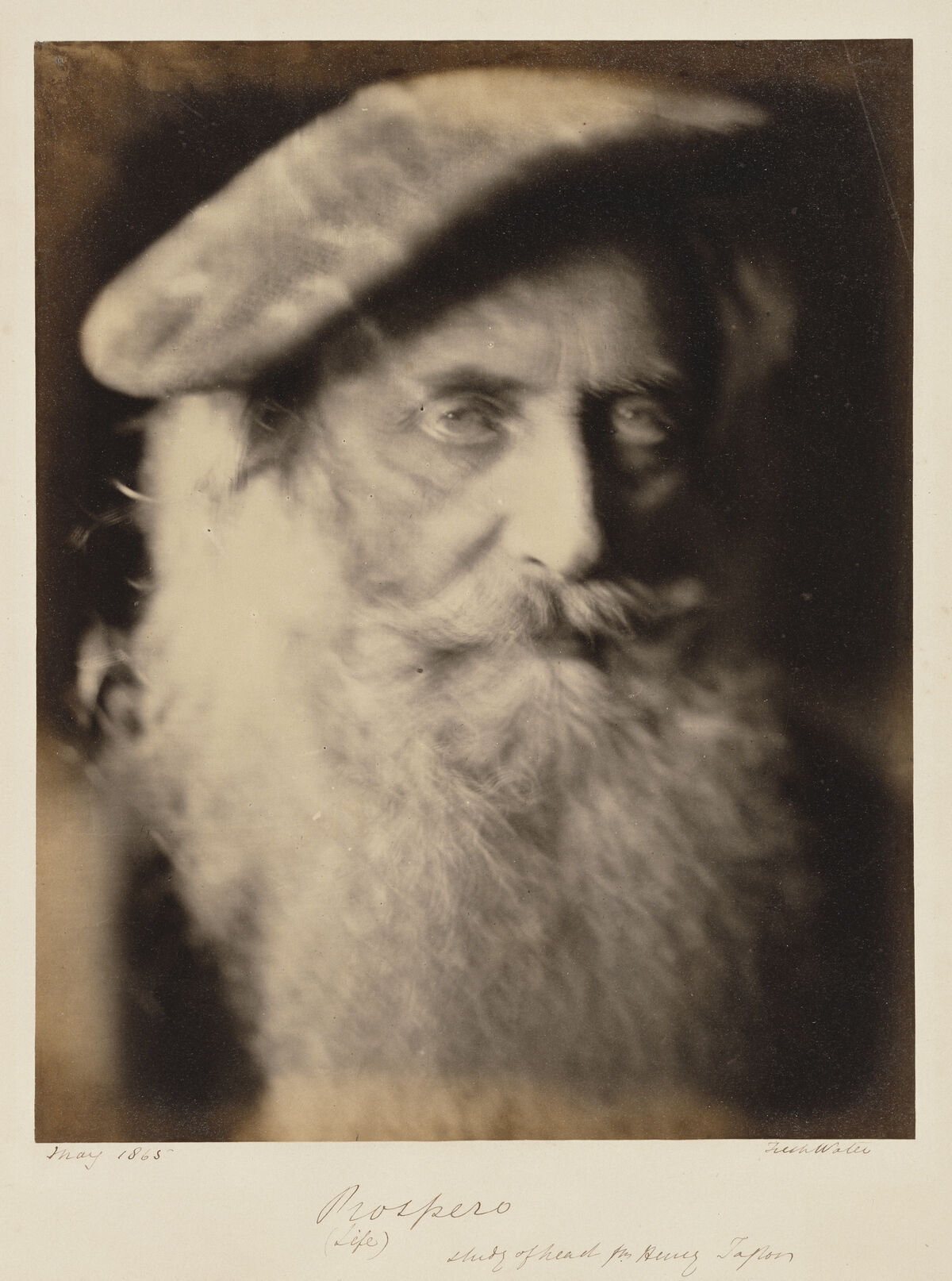

Julia Margaret Cameron, Prospero (Study of Henry Taylor), 1865. Photo via The J. Paul Getty Museum.

In the Victorian age, where childhood was venerated as a kind of idealized innocence, adolescence barely existed; the teenager wouldn’t be “invented” for another century. And yet Hawarden, whose images feel somehow contemporary, captured a languorous, listless quality that feels definitive of those coming-of-age years. Her daughters dress and undress. They act out strange courtships. They wait for adulthood. Mostly, they sit and ruminate. They could be characters in Sofia Coppola’s film The Virgin Suicides. In Hawarden’s portrayal, idleness is full of imaginative potential.

Hawarden exhibited work in two Photographic Society of London shows in her lifetime, but her photographs were never published. Despite that, in 1863, The Photographic News recommended “every portrait photographer to possess and study” her brilliantly composed images. What influence they had on photographers of the era—before they disappeared into family albums for almost a century—is unknown, though some critics believe they inspired

’s infamous “Symphony in White” paintings.

Today, Hawarden’s work is often compared to

’s oeuvre. Hawarden’s arrangement of her daughters—who seem more knowing, more three-dimensional than other Victorian children—tends to be considered faintly risqué. Their ambiguous, erotic undertones have also made them a lightning rod for queer interpretations, invigorating Hawarden’s relevance for contemporary viewers.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Il Penseroso, 1864. Photo via The J. Paul Getty Museum.

![Julia Margaret Cameron, Professor [Benjamin] Jowett, 1864. Photo via The J. Paul Getty Museum.](https://d7hftxdivxxvm.cloudfront.net/?resize_to=width&src=https%3A%2F%2Fartsy-media-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com%2F6mJ5xwM57KVI9RsUHffRJQ%252FProfessor%2B%255BBenjamin%255D%2BJowett%252C%2B1864.jpg&width=1200&quality=80)

Julia Margaret Cameron, Professor [Benjamin] Jowett, 1864. Photo via The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Another pioneering 19th-century female photographer whose relevance needs no reinvigoration is

(1815–1879), who was given her first camera at age 48, supposedly to distract her from melancholy while her husband was investigating a failed coffee crop in Sri Lanka. Up until then, Cameron had been a mere accessory to greatness, playing host to male grandees (including poet and painter

and authors Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray) who came to the salons that she and her sister, Sarah Prinsep, organized in London. Yet Cameron would become one of the very greatest photographers of all time—certainly one of the greatest British artists of the century—and produce the most striking images of the poet Alfred Tennyson, who was her neighbor.

Cameron had an artistic temperament to match. She once locked her adopted daughter in the cellar so she would better embody “despair.” She was a perfectionist with an unshakeable belief in her work, and she heeded no criticism, which angered male contemporaries, such as

. Many didn’t appreciate what a 1868 review in The Photographic News called her “willfully imperfect” style, which featured dramatically lit subjects—who were often famous—wreathed in a wistful blur, as in Prospero (Study of Henry Taylor) (1865) or an 1866 portrait of her niece Mary Prinsep. Cameron favored lenses that required long exposure times, and her trademark soft-focus was sometimes due to subjects inevitably moving, their essences seeming to come free. She “used badly made lenses to destroy detail, and appears to have them specially built to give poor definition,” writes Beaumont Newhall in The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present.

Unlike

,

, and Carroll—who prized polish and consistency—Cameron never doctored her photos. She embraced flecks, pinholes, and wear and tear. Her art invited the messiness of life into its frame; she even charged more for works that had fallen victim to unique accidents. While

painting had adorned soap advertisements of the period, Cameron’s art was moving towards French

in both look and theory, with the artist’s subjective experience directly shaping how the subject appeared.

Cameron can be seen as even more radical when we consider that, in her time, photography was still in its earliest days; there was, as yet, no establishment to rebel against. But she did it anyway. Cameron worked against photography itself in order to take a great picture. And like many radicals, she wasn’t fully understood in her lifetime.

Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Portrait of Theodore Roosevelt as Governor, c. 1899. Photo via the Library of Congress.

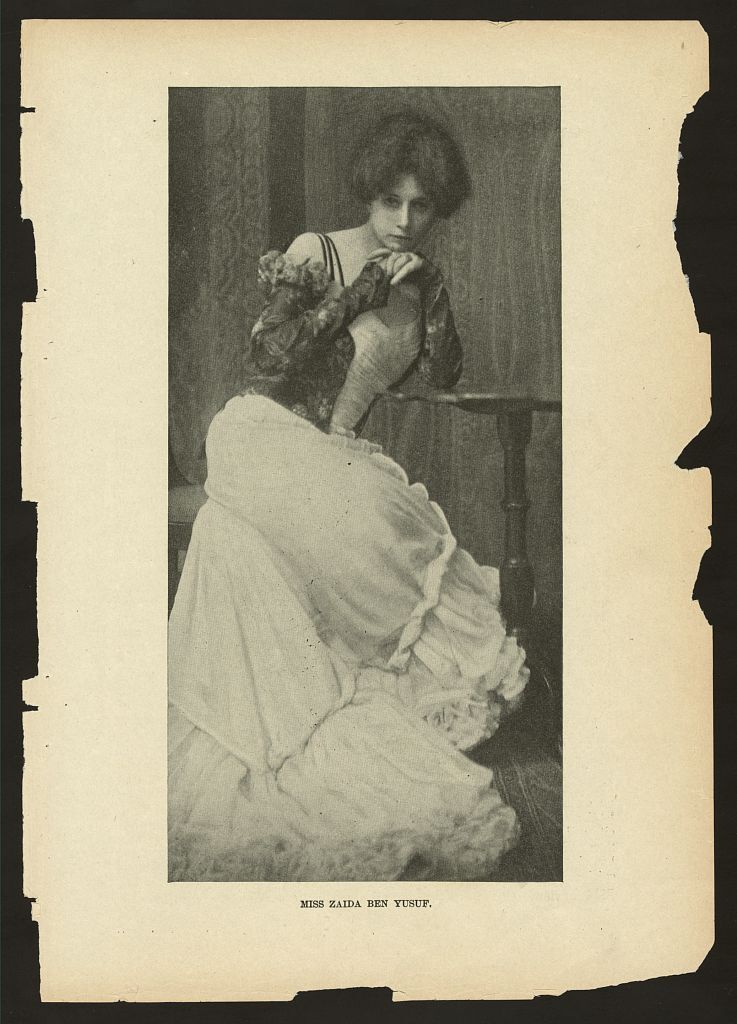

Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Miss Zaida Ben Yusuf, 1901. Photo via the Library of Congress.

A generation later, Zaida Ben-Yusuf (1869–1933), an English photographer with Algerian and German parents, moved to New York in 1895 with Cameron on her mind. From her Fifth Avenue studio, Ben-Yusuf became one of the most in-demand photographers in the city. Like Cameron, she imbued photographic portraits with the creative and atmospheric qualities of painted ones: interpreting what is seen, not just showing it. Ben-Yusuf even realized a dream that Cameron held: to make art and support herself doing it.

A woman of color with a troubled, financially unstable life in England, Ben-Yusuf came to America as a milliner. She told the critic Sadakichi Hartmann in an 1899 profile that her ambition was to be the “Mrs. Cameron of America” by photographing as many notable figures as she could. Her illustrious subjects included the novelist Edith Wharton and Theodore Roosevelt, before he became president.

Ben-Yusuf was also one of the first women to turn the camera on herself repeatedly, which she did in 10 portraits, starting with Portrait of Miss Ben-Yusuf (1898). At the time, this wasn’t seen as cultivated subject matter—

, for one, was only photographed by other photographers. But Ben-Yusuf became one of the first photographic curators of her self-image. Selfie pioneer? One could make a case.

These women, among others, achieved incredible bodies of work in short spaces of time. Cameron was a photographer for just 12 years before her family left England and she ceased to show her work; Hawarden died young; and Ben-Yusuf closed her shop before her 40th birthday. Yet they changed the way photographers—and even future painters—looked at their subjects. Photography presented one of few arenas in which these women could innovate, and they used the medium to express unique and nuanced perspectives on their worlds.

Jonathan McAloon

No comments:

Post a Comment