Visual Culture

The 19th-Century Botanist Who Changed the Course of Photography

Anna Atkins, Dictyota dichotoma, in the young state & in fruit, from Part XI of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1849-1850. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Anna Atkins, Alaria esculenta, from Part XII of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1849-1850. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then photo books offer even richer narratives. Invented in the 19th century, the form allows for pictorial storytelling, in collectible format. Carefully arranged images convey a photographer’s larger aesthetic aims:

’s iconic 1958 monographThe Americans offers a lyrical glimpse of post-war society, while

’s 1986 book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency still induces nostalgia for New York bohemia. Unlike the temporary nature of an exhibition, photo books are always available for return visits.

The tale of photo books themselves began in 19th-century England, with a surprising subject matter and inventor: an amateur botanist named Anna Atkins, whose work is straightforwardly described in the book’s title, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions.

Raised in restrictive 1800s Britain,Atkins created her groundbreaking document with support and mentorship from her progressive, scientist father, John George Children. Atkins’s monograph proved that a new creative medium also had important practical implications for non-artistic disciplines.

Unknown artist, Anna Children, ca. 1820. From the Nurstead Court Archives. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Unknown photographer, Portrait of Anna Atkins, ca. 1862. From the Nurstead Court Archives. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Atkins was born in 1799 in Kent, England, and was raised by Children, her mother having died shortly after childbirth. Children, a chemist, encouraged Atkins’s developing passion for botany. Though society dictated strict gender roles—women were expected to be content as homemakers—Children wanted to raise his daughter differently. He offered Atkins and her friends science lessons, and employed Atkins as his lab assistant.

Atkins was also intrigued by photography, a medium still in its nascent stages. She maintained a correspondence with William Henry Fox Talbot, who pioneered the early field of photography. In 1841, Talbot had patented the calotype, which employed a light-sensitive paper coated with silver nitrate that, when exposed to light, recorded light and shadow.

Talbot wasn’t the only Brit to experiment with photography. Children’s circle of friends included Sir John Herschel, an astronomer and chemist who, in 1842, developed another light-sensitive paper that recorded images against a blue background, which he called the cyanotype. The form became a means of reproducing drawings, in particular, architectural blueprints.

In 1841, English physician William H. Harvey published Manual of British Algae; Atkins found the work visually insufficient. Indeed, Harvey had listed and described all the new algae specimens he could find, without offering any illustrations. Atkins, empowered to create her own version, made cyanotypes to imprint the images of algae for posterity. Herschel himself probably taught the process to Atkins.

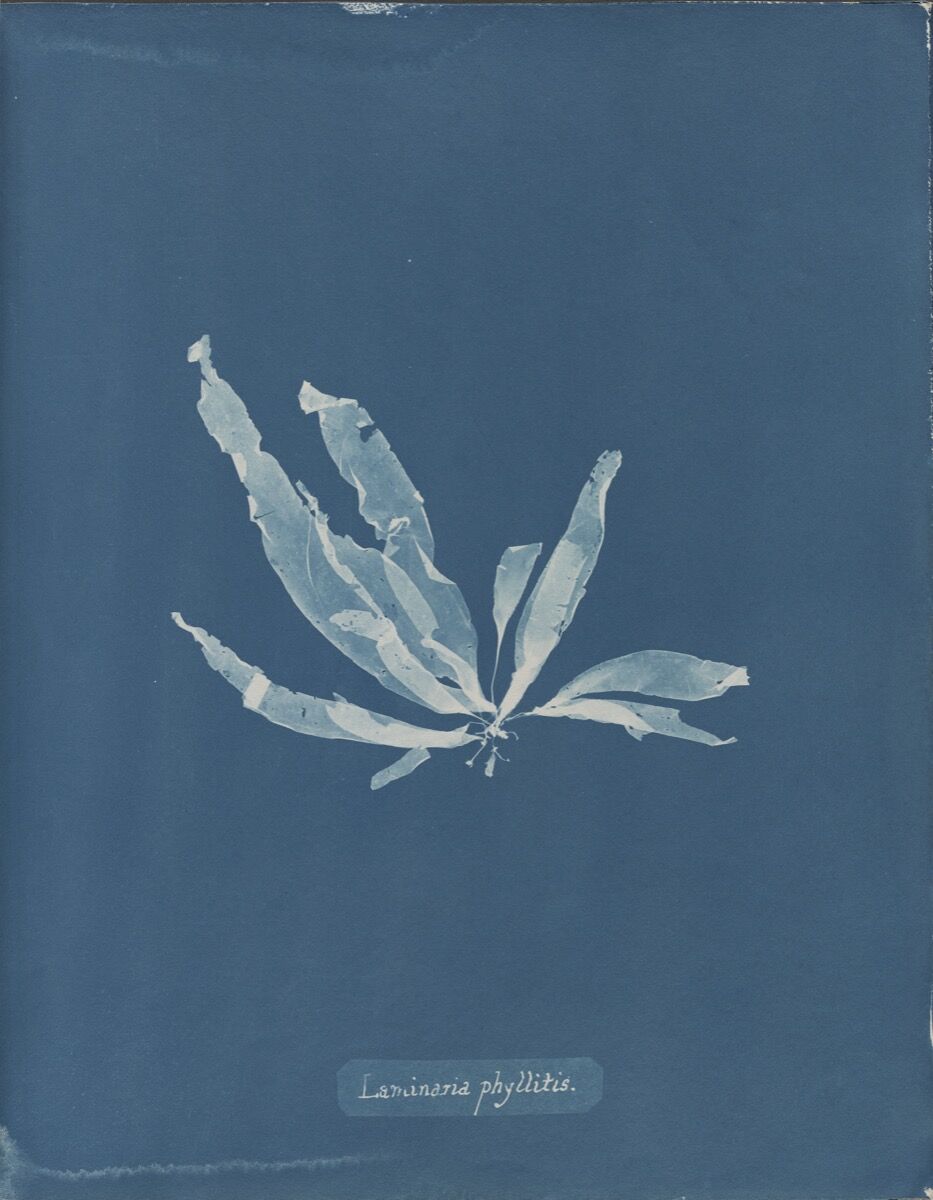

Anna Atkins, Laminaria phyllitis, from Part V of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1844-1845. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Anna Atkins, Ulva latissima, from Volume III of Photographs of British Algae Cyanotype Impressions, 1853. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Today, algae might seem a rather banal subject for history’s first book of photography. Yet New York Public Library curator Joshua Chuang believes that Harvey’s manual and Atkins’s subsequent work were part of a larger natural history craze in Britain. People were cataloging plant life, attempting to harness the multiplicity of nature. “[Some] of the great mysteries of the natural world [were] things from the sea,” he said. “And algae were accessible, beautiful, and various.”

This fall, Chuang is mounting two exhibitions at the library: “Blue Prints: The Pioneering Photographs of Anna Atkins” and “Anna Atkins Refracted: Contemporary Works” (co-curated by Elizabeth Cronin, the NYPL’s assistant curator of photography). The first exhibition examines Atkins’s achievements, while the second addresses Atkins’s influence on and resonance within contemporary art practice.

“Blue Prints” will include multiple copies of Atkins’s photo-illustrated manuscript. Between 1843 and 1853, she created and distributed the pages filled with cyanotypes that would become her book, distributing the tome in parts, bound in soft covers. Atkins sent the book to acquaintances, who had to visit bookbinders to sew the different sections together. In all, Atkins produced 17 handmade copies; because of her process, however, no two were alike.

Anna Atkins, Nitophyllum gmeleni, from Part XI of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1849-1850. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

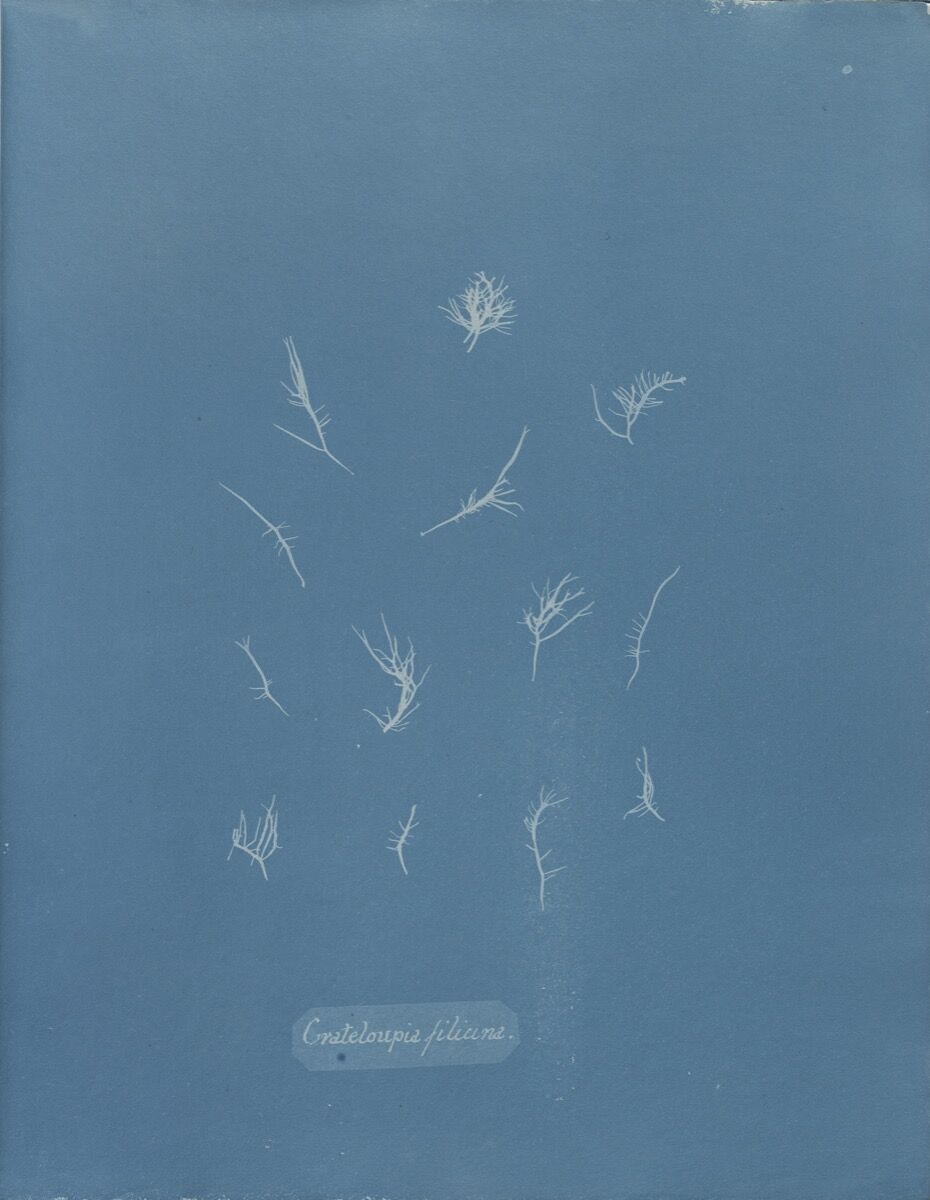

Anna Atkins, Grateloupia filicina, from Part IX of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1848-1849. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

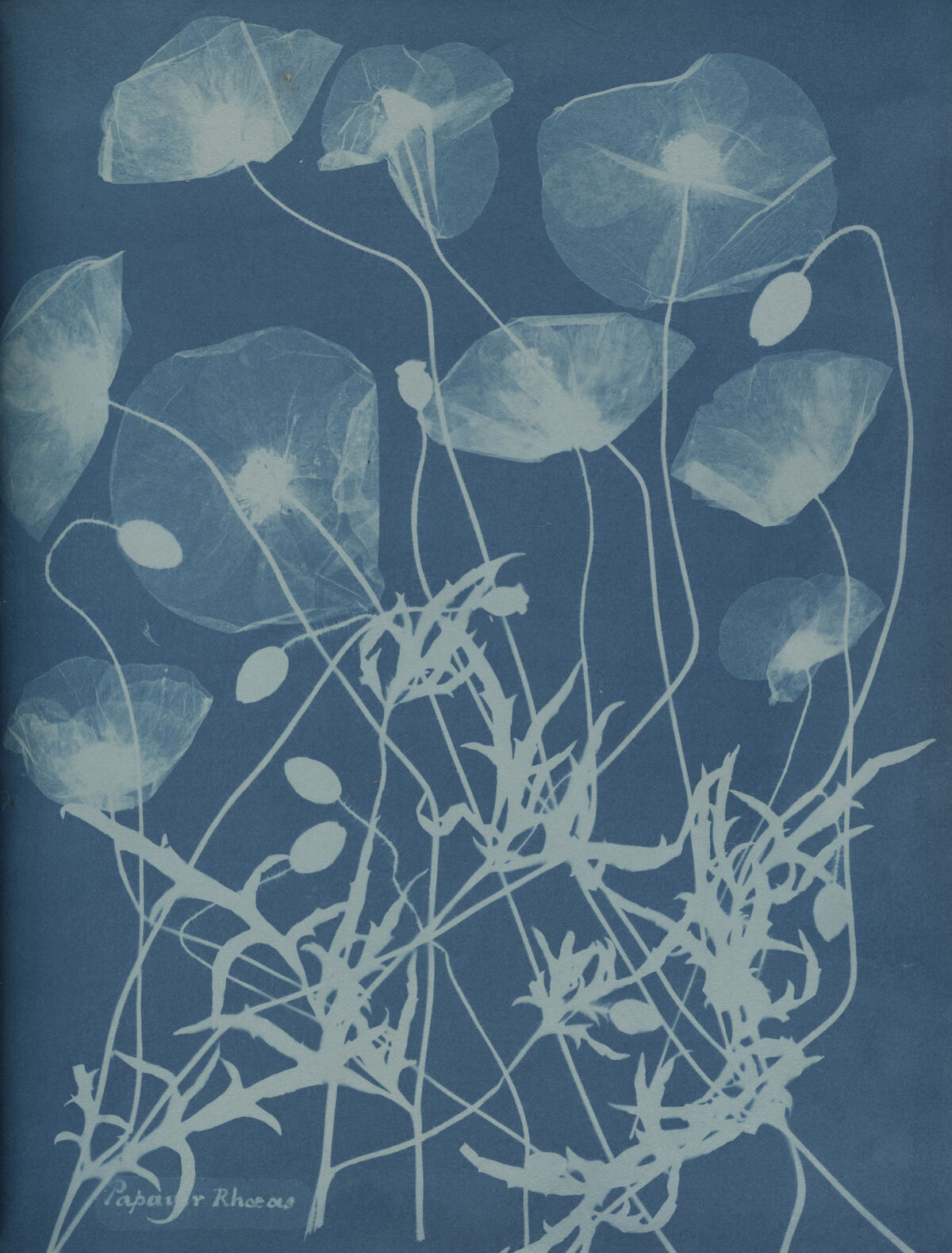

Today, Atkins’s book manifests an ethereal beauty. White, feathery outlines of algae ripple across deep blue backgrounds. Elegant white type along the bottom of each cyanotype gives each species’ name—all sounding, to the untrained ear, more like mystical incantations than botanical designations: Chordaria flagelliformis, Polysiphonia affinis, Cystoseira granulata.

When Atkins died in 1871, her name faded in and out of history. Influential personalities of her time, including Scottish book collector William Lang Jr., recognized her achievement. In 1864, Lang read an article by Talbot about non-silver photographic processes that mentioned Atkins’s work, without mentioning her name. “Lang was so entranced that he thought to himself, ‘I have to find a copy,’” recounted Chuang. After a several-year search, Lang identified a London bookseller with the manuscript and bought it in 1888. He wrote an article about the book in an 1889–90 volume of the Proceedings of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow.

Lang, however, still wasn’t sure who’d created the book: Atkins had signed her work “AA,” leading him to conclude that the initials stood for “Anonymous Amateur.” A few weeks after Lang published his piece, a curator from London’s Natural History Museum wrote to the journal editor and said that he, too, owned a copy of the book in question, and he knew it was by a Mrs. Atkins. Lang embarked on a series of public exhibitions and lectures, conducting, said Chuang, something “almost like an Anna Atkins roadshow.”

Anna Atkins and Anne Dixon, Papaver rhoeas, 1861. Private collection. Courtesy of Hans P. Kraus, Jr.

Anna Atkins and Anne Dixon, Peacock, 1861. Private collection. Courtesy of Hans P. Kraus, Jr.

Lang’s finances suffered towards the end of his life, and he had to sell off a portion of his library that included Photographs of British Algae. When he died in the early 1900s, Atkins lost a major champion. According to Chuang, a 1955 history of photography included her name, along with just a few sentences.

Finally, in the 1970s, an art historian named Larry Schaaf, working at the University of Texas at Austin, discovered Atkins’s work and attempted to piece together her biography. “He basically put her on the map not only as a pioneer of photography, but also the first person to publish a photographically illustrated book,” said Chuang. In 1985, Schaaf helped re-publish Atkins’s work in Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms.

In the years since, contemporary curators have bolstered Atkins’s reputation. In 2004, the Drawing Center in New York and the Yale Center for British Art organized a show—“Ocean Flowers: Impressions from Nature in the Victorian Era”—of 19th-century botanical photography, which included prints by Atkins alongside those of Talbot and Herschel. A 2010–11 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, entitled “Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography,” included Atkins’s cyanotypes alongside work by

,

, and other women photography leaders.

Curators, scholars, and artists alike are ensuring that Atkins’s name remains integral to art canon. Her story, like so many others, reminds us that artistic innovation isn’t enough to secure an adequate legacy—future generations must write about and champion worthy projects. Atkins’s brilliant work, which was nearly lost to history, is getting a new chance to shine.

Alina Cohen is a Staff Writer at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment