What is good comedy? The answer probably depends on your social background

Among the 1,000 or so comedians who have been jostling for attention at this year’s Edinburgh festival fringe, two grabbed a disproportionate amount of headlines. Both occupy prime slots in big venues and both are receiving regular standing ovations.

At one end of Edinburgh’s salubrious Old Town, in the enormous Pleasance Grand, the alternative comedy poet Tim Key is serenading hundreds with his beautifully strange comedy verse. He writes them on the back of pornographic playing cards and reads them aloud before tossing them nonchalantly into the ether.

A few minutes walk away in the equally impressive Assembly Hall (and at precisely the same time) veteran standup Jim Davidson is peddling a very different “alternative” comedy – challenging the mainstream with an “old school” blend of physical comedy and proud political incorrectness.

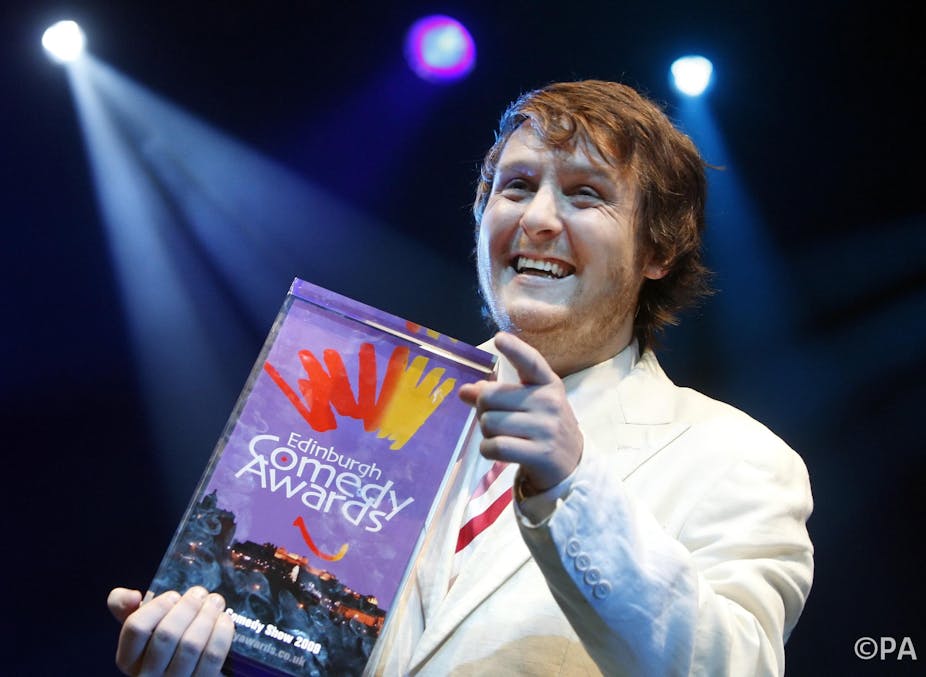

While both comics appear to be a hit with audiences, the same can’t be said for Edinburgh’s army of comedy critics. While Key – winner of last year’s prestigious Edinburgh Comedy Award – continues to clock up glowing reviews, Davidson has been roundly mauled. As a critic and magazine publisher at the fringe I’ve always been fascinated by what makes different audiences laugh and, at the same time, how critics struggle to define whose laughter is or isn’t legitimate.

This interest prompted me to start investigating comedy on an academic level. And so between 2008-2012, I carried out the first ever empirical study of British comedy taste, surveying 900 people at the Edinburgh fringe (the biggest comedy festival in the world). I asked them about their preferences for stand-up and comedy TV shows, and then followed up with 24 interviews so I could look at people’s sense of humour in more detail.

What I uncovered was striking. My survey revealed that there are very strong divides in what people funny, and that these taste differences are strongly associated with socio-demographics. What was most noticeable in shaping these differences is what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called “cultural capital”.

This refers to highly prized dispositions and cultural knowledge that upper-middle class parents tend to pass on to their children.

So those in the upper middle classes, particularly younger generations, tend to prefer critically acclaimed comedians such as Tim Key. Whereas those with low cultural capital, particularly older generations, tend to prefer less critically legitimate comedians, such as Jim Davidson. This division is important because it both contributes to, and reflects, the idea that certain comedians are “special” cultural objects.

The main source of this power was the perceived rarity of certain comedy. During interviews I observed how those from all backgrounds seemed to accept the assumption that comedians like Tim Key were somehow more “difficult” to consume. So enjoyment of these comedians infers a certain cultural aptitude. Watching such comedy was, in the words of one respondent, like “sitting an exam”. One must possess extensive reserves of comedy-specific knowledge in order to decode the humour. In contrast, many respondents with less cultural capital admitted puzzlement and failure in the face of this supposedly “highbrow” comedy, reporting that such humour “went over their head”, or that they simply couldn’t “get it”.

While questionnaires can tell you what people like (and dislike), it can only provide limited insight into why. Therefore, in interviews, I set out to examine the way people read comedy. Strikingly, I found that those well endowed with cultural capital knowingly set themselves apart. These respondents felt that comedy should never be just funny, never centre purely around laughter, or probe only what one respondent referred to as “first-degree” emotional reactions. Instead, “good” comedy should have meaning – whether this is a political message or an experiment with form. Either way, the audience should have to “work” for their laughter. These people saw themselves as carrying out an aesthetic labour so as to reach a higher plane of comic appreciation.

This was even demonstrated in terms of crossover comedians such as Simon Amstell, Jimmy Carr and Eddie Izzard. Although these stand-ups were liked by nearly all respondents, those with more cultural capital insisted they could always “get” more, extracting what one respondent described as a “whole other level” of humour.

All this says a lot about the reactions to Key and Davidson at this year’s fringe. While both may be confidently branded hilarious by their fans, some people’s notion of “funny” may be significantly more powerful than others. Buttressed by critical acclaim, I would argue that comedians like Tim Key have become important markers of cultural capital in Britain today. It is their “highbrow” approach and perceived interpretative difficulty that tend to win the awards and accolades – and in turn bestow a special status on those who successfully “get” the jokes they tell.

No comments:

Post a Comment