Private Eye circulation soars as readers turn to satire – funny that

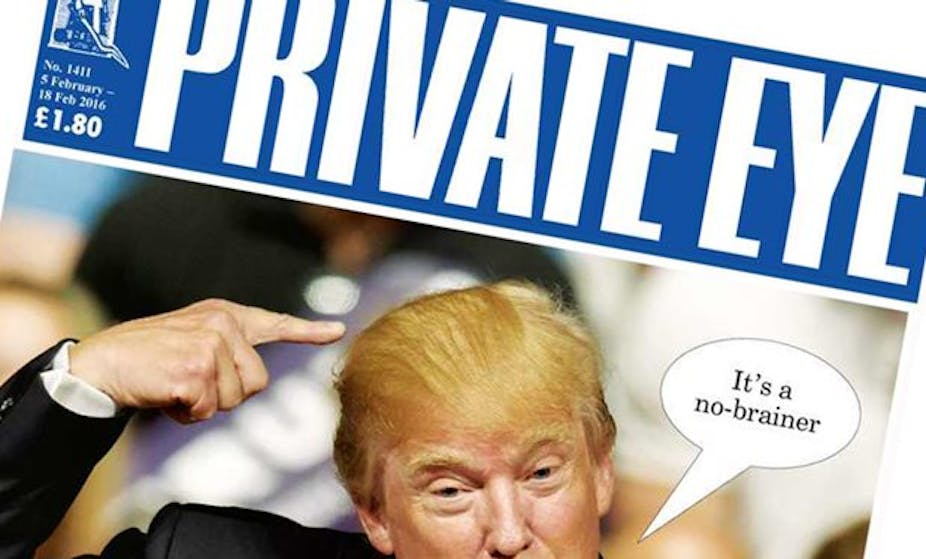

It’s a fair bet that champagne corks have been popping at Gnome House, the abode of Lord Gnome, the (fictional) proprietor of the satirical magazine, Private Eye since the latest circulation figures were released. This is because, running contrary to the usual news about the moribund printed press, the Eye recently recorded its largest-ever circulation figures.

And, according to reports in the Press Gazette the 2016 Christmas issue was a real blockbuster selling some 287,334 copies and weighing in as the biggest single sale in the 55-year-old magazine’s existence.

Understandably, Ian Hislop, editor of Private Eye since 1986, did little to contain his delight. He told the Press Gazette that there had been no additional marketing, such as bulk giveaways involved in the achievement – people really were just buying the magazine. He added:

I know we are niche and we are fortnightly but it is about having confidence in the reading public. I do think if people will pay £2.50 for a cup of coffee then they will pay [£1.80] for a copy of the Eye.

Private Eye is not alone. The Economist, in a generally glowing six-monthly report, revealed in June 2016 that print sales were up 2.1% year-on-year while The Spectator reports that its UK print sales are up by 10% in a year – which builds upon the success of 2016 when the political magazine broke circulation records and sold more copies than at any time in its 189-year history. Also doing well are The Week, the New Statesman and Prospect.

And in France, Le Canard enchaîné, which recently celebrated its 100th birthday, is also in rude health despite carrying no advertising and a relatively low cover price of €1.20 (£1) per copy.

Bonding with readers

So what is it about these current affairs magazines that sees them buck the trend? First of all, the relationship between the reader and their periodical has always been unique. The connection is ritualistic and forged on a bond of trust. The reader knows exactly what they will get from one week to the next. This is why advertisers have traditionally been attracted to advertising in magazines. A close and tangible bond between reader and text renders, in theory anyway, the customer to the advertiser in a receptive frame of mind.

Private Eye’s online presence is minimal, just a taster – to get the full experience you simply have to buy a copy of the printed magazine. And many people do – the subscription model is key to the Eye’s success – as Campaign magazine reported recently, 57.1% of Private Eye’s worldwide sales come from subscriptions.

Hislop is right to say that the Eye is niche. But the magazine enjoys an especially close bond with its readership, defined by a series of codes and in-jokes. Whichever party is in power – and however vicious or ridiculous the political landscape – the Eye is there with its regular features and, to the casual reader, impenetrable series of cryptic references and stock phrases.

Herein lies one of the secrets of its success. For Private Eye to be fully understood, readers need to persevere. There’s a certain (some might say smug?) satisfaction at getting jokes that others may not. It creates a shared intimacy between the Eye’s editorial team and its readers. As media academics Steve Neale and Frank Krutnik assert in their book about comedy, such jokes “create a communal bonding between the participants which establishes a relationship of power, of inclusion and exclusion”.

But Private Eye is not just about jokes, cartoons and newspaper misprints. A fundamental part of the magazine’s appeal lies in its commitment to investigative journalism. Over the years it has built its reputation by challenging the rich and powerful – frequently exposing itself to expensive libel cases. Quite often Private Eye has led where the conventional press has feared to tread.

Beginning with the Profumo case in 1963 and through the work of the late Paul Foot, the magazine has never been afraid to tackle public figures (James Goldsmith, Robert Maxwell) and address issues (the deaths at Deepcut barracks) that would have in all likelihood remained uninvestigated. In this sense the Eye remains, to the majority of its readers, a trustworthy source of information.

Truth to power

We may also be living through a golden age of satire and Hislop partially attributes the recent success of Private Eye to the “extraordinary” 2016 and the rise of Trump and the Brexit vote. Just about everything, he told the Guardian, makes good satire.

As Guardian columnist and sociologist Anne Karpf recently put it, laughing at powerful elites makes them seem less omnipotent. While the long-term effectiveness of satire to contribute to political change is open to question, some of the most powerful critiques are coming from the scathingly brilliant Frankie Boyle in the UK and the relentlessly dedicated Saturday Night Live team on NBC television in the US.

Melissa McCarthy’s superbly realised impersonation of Sean Spicer, Trump’s press secretary and communications director at the White House, has to date been viewed nearly 23m times on YouTube. You could argue that Spicer has been architect of his own misery but SNL’s habitual takedowns of Trump and his allies have certainly added to a prevailing attitude of outright ridicule and disdain which now seems to be directed at the White House from cultural quarters.

But back to Private Eye. As media academic Steven Wagg noted, though the Eye has always been at the heart of British satire it has been steadfastly conservative on cultural questions. But it is also responsible for, as part of a wider satirical tradition, creating an environment where those in power can be both lampooned for their idiocies and held to account for their excesses.

Perhaps it is this dual purpose, in this post-truth era, which is at the root of Private Eye’s continuing success.

No comments:

Post a Comment