Art

The Most Remarkable Art-Historical Discoveries of 2017

Art history is, by definition, primarily a thing of the past—but each year, some small portion of it is rewritten by those in the present. In 2017, we gained new insight on the early years of Leonardo da Vinci and the final ones of Andy Warhol; amateur archaeologists were rewarded with major finds; and several masterpieces were discovered, simply hiding in plain sight. From newly mapped Venezuelan petroglyphs to a long-lost Magritte, these are 10 of the most notable art-historical discoveries of the year.

A slew of ancient tombs and artifacts have been uncovered this year in Egypt, in a concentrated effort to promote tourism.

Photo by Ibrahim Ramadan/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

Earlier this month, the country’s ministry of state for antiquities announced the discovery of two roughly 3,500-year-old tombs in the necropolis of Draa Abou Naga in Thebes, near the southern city of Luxor. Although the deceased occupants have yet to be identified, researchers have dated the structure to the 18th dynasty (1550–1292 B.C.) and have found a number of artifacts, including funerary furniture, painted wooden masks, and approximately 450 statues. Perhaps the most impressive find is a remarkably well-preserved wall painting. “It looks like it was painted yesterday,” Egyptologist Zahi Hawass told the Independent. “In my opinion, this could be the best painted wall discovered in Draa Abou Naga in the last 100 years.” Another 3,500-year-old tomb in the same necropolis—this one constructed for a royal goldsmith named Amenemhat—was revealed in September. And in March, pieces of a 26-foot statue of a pharaoh (likely King Psammetich I, who ruled between 664 and 610 B.C.) were pulled from a muddy ditch in a working-class neighborhood in Cairo.

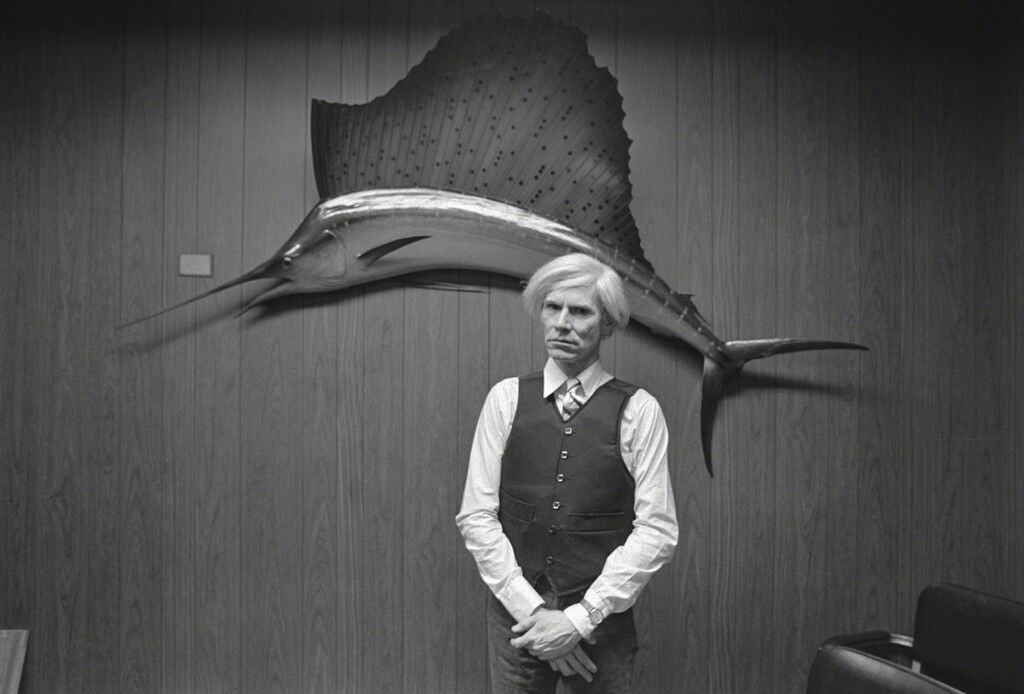

Andy Warhol’s untimely death was the result of long-running health problems, not a routine surgery gone wrong.

When the famed Pop artist died in 1987 at age 58, newspapers were shocked that a simple operation like a gallbladder removal could have spurred the heart attack that killed him. And, in the three decades since, that’s remained the prevailing view. But new research, presented in February by medical historian and retired surgeon Dr. John Ryan, indicates that Warhol had actually suffered gallbladder problems for almost 15 years. (Ryan has been researching the artist’s death since his retirement four years ago, encouraged by his brother-in-law, the prominent art historian Hal Foster.) Warhol’s condition was so severe that, during the 1987 surgery, the doctor found Warhol’s gallbladder full of gangrene—so full, he said, that the organ fell apart during removal. The artist’s health was worsened by an addiction to speed, severe malnourishment and dehydration, and the long-term effects of a 1968 gunshot wound at the hands of Valerie Solanas. That final gallbladder operation, it seems, was ultimately too stressful for his fragile body; Warhol’s heart gave up hours after he appeared to be recovering from the surgery.

A team of amateur archaeologists dug up one of the most significant Roman mosaics ever discovered in Britain.

The discovery was made in a field outside of Boxford, in southern England, by a group of local volunteers supervised by professional archaeologists. Although the project began in 2011, it wasn’t until August of this year—during the final two weeks of the scheduled dig—that organizers realized they’d found something extraordinary. As it turned out, they’d uncovered a remarkably well-preserved mosaic, built as part of a Roman villa that dates to roughly 380 A.D. Not only is it a rare find for the country—experts have labeled it the most exciting of its kind unearthed in 50 years—the subject and style of the artwork is highly unusual for the area. The work illustrates the story of Bellerophon, a Greek mythological hero tasked with killing the Chimera. Anthony Beeson, a board member of the Association for Roman Archaeology, told the New York Times that he couldn’t think “of another Roman mosaic in this country that is as creative as this one.”

A Vatican fresco, once attributed to Raphael’s followers, contains two figures painted by the Renaissance master himself—both of which have now been identified.

The allegory of Justice in the Room of Constantine. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The discovery was made in the Room of Constantine, a reception room in the papal apartments decorated with episodes from the life of the first Christian emperor. This space was one of four grand halls that Raphael had been commissioned to paint by Pope Julius II in the early years of the 16th century. Although the artist sketched out a design for the room, his unexpected death in 1520 at age 37 left his workshop to complete the project. Contemporary sources did note that Raphael had painted two figures in the hall shortly before he died, but until a recent restoration project, it had been impossible to identify which ones. In June of this year, the Vatican revealed that two painted women—allegorical representations of friendship and justice—had the mark of the master’s hand. “By analyzing the painting, we realized that it is certainly by the great master Raphael,” restorer Fabio Piacentini said. “He painted in oil on the wall, which is a really special technique.”

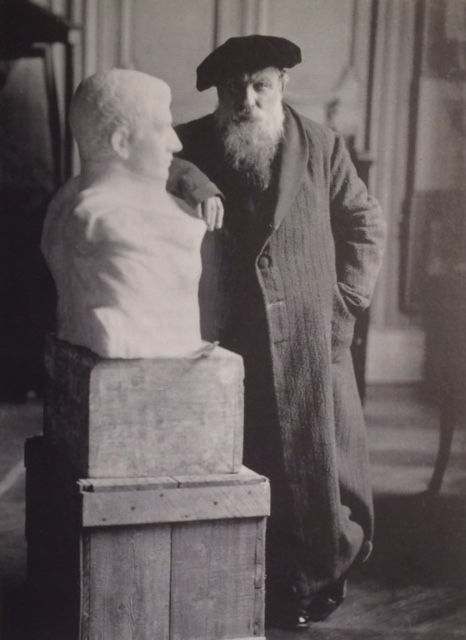

A major work by Auguste Rodin was found gathering dust in a New Jersey borough hall.

Auguste Rodin with his sculpture of Napoleon Bonaparte. Courtesy of the Hartley Dodge Foundation/Musée Rodin.

The marble bust of Napoléon Bonaparte (c. 1908) had been sitting in the Madison, New Jersey, town hall committee room for 75 years. It wasn’t until a private foundation hired an archivist—a 22-year-old graduate student in art history—that the work’s creator was properly identified as the famed Rodin. Further research revealed that the sculpture had been purchased by Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge, an enthusiastic art collector and the daughter of William D. Rockefeller, in 1934. Also the owner of a 300-acre estate in Madison, Dodge often selected artworks from her personal collection to decorate the borough hall. This Rodin was evidently one of them, but the transfer process was clearly informal; no paperwork or documentation accompanied the bust, and after Dodge’s death, its provenance was forgotten—until now. The rediscovered sculpture has been valued on the range of $4–12 million. Due to security concerns, it has been loaned to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A Leonardo da Vinci scholar may have solved a long-standing mystery concerning the artist’s biography.

It was a big year for Leonardo. Not only did a rediscovered painting by the Renaissance polymath sell for a record-shattering $450 million at auction, but experts may also have determined the identity of the artist’s mother. For centuries, historians have only had a potential first name—Caterina—to go on. But a new book, based on previously overlooked financial documents from Vinci and Florence, pinpoints a poor orphan named Caterina di Meo Lippi. Seduced by a 25-year-old lawyer when she was just 15, she probably received a small dowry from his family and was soon married off to another man: Antonio di Piero Buti, a local farmer. New research in the book also contests the site of Leonardo’s birth, long believed to be the Casa Natale in Anchiano.

A portrait by Peter Paul Rubens, missing for almost 400 years, was discovered hanging in a historic Glasgow house.

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham, ca. 1625. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Bendor Grosvenor, host of the BBC4 television series Britain’s Lost Masterpieces, spotted the painting while vacationing with his family in Scotland. “This picture just seemed to stand out,” he told Artsy in October. “I could see from the bits that were visible and not overpainted that some of it looked very Rubensian.” Although the portrait had previously been dismissed as “merely a copy,” after two months of cleaning and conservation work, it was determined to be an original work by the 17th-century Flemish painter. (It is, however, a study for a larger painting, not a final version of the portrait.) The subject, George Villiers, was the first Duke of Buckingham—and, some have surmised, the male lover of Scottish king James VI and I. Glasgow Museums, which maintains the art collection of the Pollok House (where the portrait was first discovered), has placed the rediscovered work on display in its main gallery.

A miniscule carving recovered from a Bronze Age tomb revealed detailed handiwork centuries ahead of its time.

Although the 1.4-inch-long etched gemstone was found two years ago in southwest Greece, it was initially set aside for later study; researchers assumed it was nothing more than a simple bead. But after a careful, almost year-long cleaning, a tiny work of art etched onto the surface of the agate was discovered: a warrior stabbing an enemy in the neck, with another slain man at his feet. The full details are only visible through a microscope or heavy-duty camera lens, although no tools for magnification have been ever been found from the corresponding time period. Researchers have wondered if, perhaps, the ancient artist was nearsighted. A professor from the University of Cincinnati who aided in the discovery noted that it would be another millenia before other artworks displaying that level of detail begin to appear in ancient Greece.

Eighty-five years after it went missing, the last piece of a lost René Magritte painting was found in Belgium.

René Magritte, The Enchanted Pose, 1927. © Succession René Magritte. Courtesy of SABAM © ULiège.

In November, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium announced that researchers had discovered the fourth and final section of Magritte’s work The Enchanted Pose (1927). X-ray imaging revealed that the Surrealist artist had painted over it to create a later work, God is not a Saint (1935–36), today owned by the Magritte Museum in Brussels. Historians suspect that a penny-pinching Magritte cut the original work into four parts and painted over each one in an effort to reuse canvas and save money. This discovery completes an art-historical jigsaw puzzle that researchers began to piece together in 2013, when the first section of the lost painting was discovered during conservation work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The second piece was found in the collection of Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the third in the collection of Norfolk Museums Service in eastern England.

Thanks to drone technology, researchers have mapped massive, 2,000-year-old petroglyphs in Venezuela for the first time.

Although archeologists have known about the carvings for years, their size and their location—a group of islands within the hazardous Atures Rapids—have historically made them difficult to photograph in their entirety. These images are part of a larger project examining how pre-Columbian cultures dealt with each other, with evidence suggesting that there were indigenous trading networks for thousands of years before European colonization. Many of these newly-mapped petroglyphs represent rituals, including what may be a “rite of renewal” ceremony, as well as humans and animals—such as a roughly 100-foot-long snake.

Abigail Cain is an Associate Editor at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment