Art

From Dada to Bauhaus, How 14 Art Movements Got Their Names

As anyone who’s read an Art History syllabus or walked through the Museum of Modern Art’s fifth floor knows, the history of modern art has been dominated by groups of like-minded artists with specific aims or approaches, otherwise known as art movements. Since the late 19th century, a quick succession of radically experimental groups has responded to rapidly changing social, political, and cultural climates—leading to the formation of countless movements, and with them, dozens of -isms, acronyms, portmanteaus, manifestos, and peculiar words like “Dada.”

And the stories behind movements’ names, while sometimes quite arbitrary, are often surprisingly revealing about their members, as well as a group’s historical context and mission. Here, we dig into the names of 14 unique and influential movements in recent art history, listed in chronological order.

Sir John Everett MillaisOphelia1851-1852Tate Gallery, London

Despite name-dropping the Renaissance master Raphael, the British artists who formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 wanted nothing to do with him. Rather, founders Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt sought to emulate the aesthetics that were popular before Raphael rose to fame in 15th- and 16th-century Italy.

Raphael continued to be a major influence long after his death in 1520, particularly on the Pre-Raphaelites’ fellow British painters, who practiced what the Brotherhood viewed as a clichéd, academic style. Indeed, the conservative Royal Academy of Arts and its late 18th-century leader, Joshua Reynolds, consistently promoted Raphael as the preeminent master of painting, along with the traditional Victorian style that emphasized Raphaelesque idealism. Rossetti, Millais, and Hunt rejected all of these conventions, instead finding inspiration in the Medieval period and the Early Renaissance (eras the Academy had deemed “primitive”), as well as in literary themes.

The group grew to seven members, painting whimsical works filled with naturalism, symbolism, and light, and often signing them “PRB,” short for Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. After a few strong years, however, the Brotherhood split in 1853 once Millais joined the Royal Academy as an associate, effectively turning his back on everything the movement stood for. (Even more, he became president of the Academy shortly before his death in 1896.)

Though the Brotherhood was no more, the term “Pre-Raphaelites” remained in use around Britain for the following two decades, in reference to a larger group of artists, such as Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, who were in turn inspired by the original trio’s ideas.

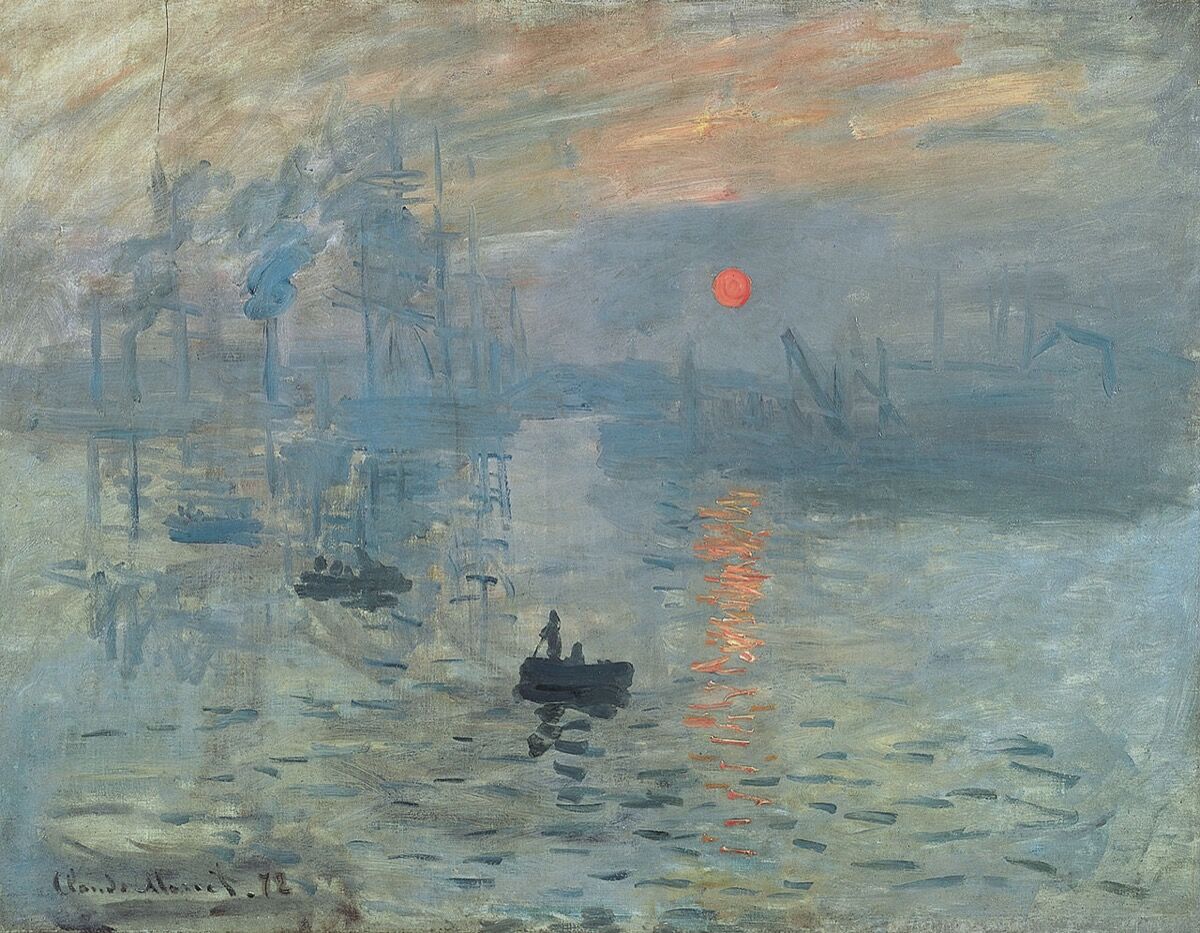

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

On April 15, 1874, a group of French artists who called themselves the Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs, etc. did what none of their peers in the Parisian art world had done before: They organized their own exhibition. Held in a vacant studio on the Boulevard des Capucines for four weeks with an admission fee of one franc, the show featured 165 works by 30 artists, including Claude Monet’s 1872 Impression, Sunrise, a pulsating, highly saturated picture rendered in quick, visible brushstrokes.

Louis Leroy, an art critic for the magazine Le Charivari, was not a fan of this painting, nor of any others in the show. He made fun of Monet’s title, writing sarcastically in his review: “I was just saying to myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in the picture…and what freedom! What ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its formative state is more finished than this seascape!” He then headlined his scathing critique “Exhibition of the Impressionists,” implying that all artists in the show—which also included works by Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir—were only capable of painting simplistic “impressions” of the world.

Harsh? Yes—but Leroy wasn’t exactly wrong. Though these artists had differing styles and subject matter—Monet’s rapid, plein air renderings of landscape scenes; Degas’s dynamically composed paintings of dancers in motion—they shared a common desire to represent fleeting moments of modern life, moments that could otherwise be called “impressions.”

And despite the term’s negative connotations, many of the artists evidently liked it. After moving through other confident names such as the “Independents” and the “Intransigents,” the group formally adopted the label of “Impressionists” by its third exhibition in 1877—a term now associated with the world’s first true modern art movement.

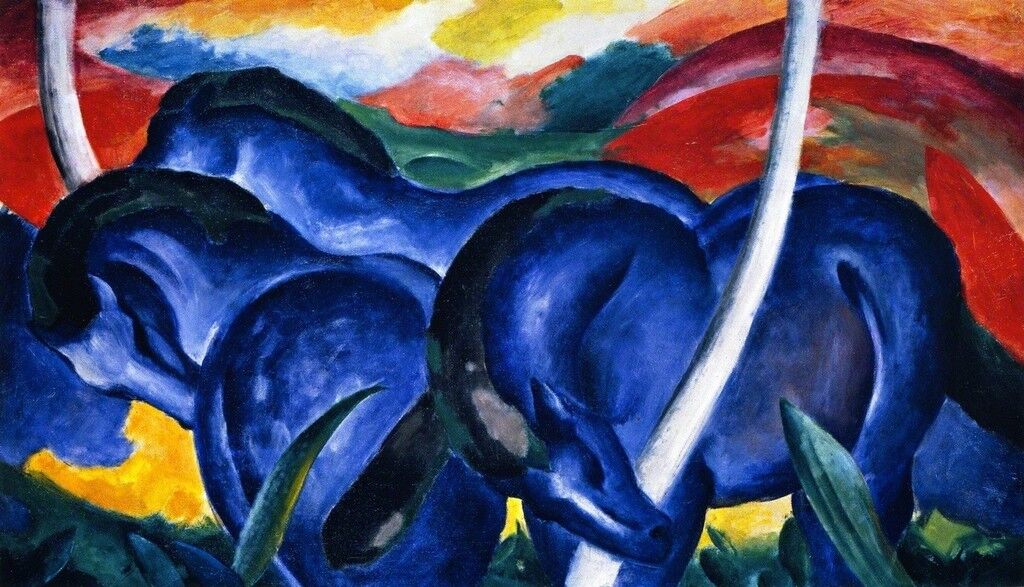

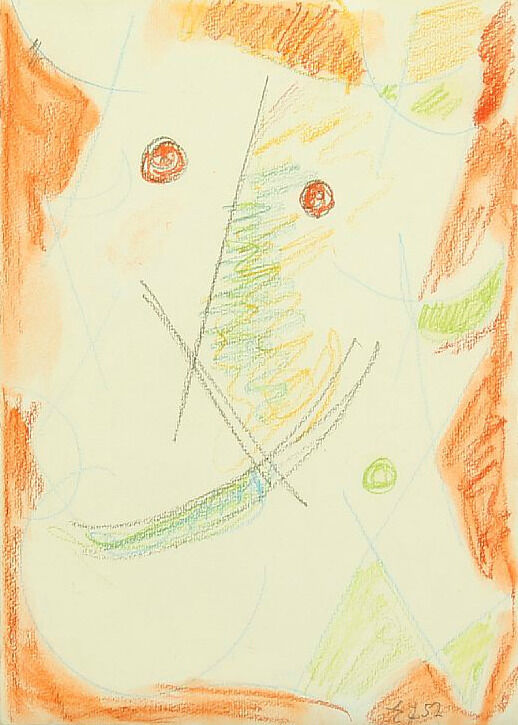

The artist group known as Der Blaue Reiter—meaning “the Blue Rider” in English—was named after a painting by one of its co-founders, the Russian émigré Wassily Kandinsky. The artist’s 1903 painting Der Blaue Reiter is a blue-tinged composition showing a figure on horseback. But the group would not emerge until the following decade, by which time Kandinsky had evolved his style, developing his synesthetic technique of rendering musical sounds visually, resulting in colorful swirling abstractions like 1911’s Komposition 4.

That same year, Der Blaue Reiter formed in Munich, with the German-born Franz Marc joining Kandinsky. By this point, the title of Kandinsky’s painting carried new meaning for him and Marc. Both artists now viewed blue as the most spiritual color, and “the rider” came to symbolize their journey from terrestrial figuration towards pure, divine abstraction. Furthermore, Marc frequently painted horses, among other animals, to represent the concept of rebirth.

Der Blaue Reiter would soon grow into a loose association of artists, including Paul Klee and August Macke. They emphasized a kind of spiritual abstraction based on the belief that colors carry metaphysical meaning. Der Blaue Reiter Almanach, published in 1912 and edited by Kandinsky and Marc, defined the significance of each hue and remains an influential writing on color theory.

The group disbanded at the outset of World War I. Years later, in 1930, Kandinsky, reminiscing about his late friend—Marc was killed on the battlefield in 1916—revealed that the two conceptualized the name almost by divine coincidence. “We both loved blue: Marc, horses; I, riders,” he said. “So the name invented itself.”

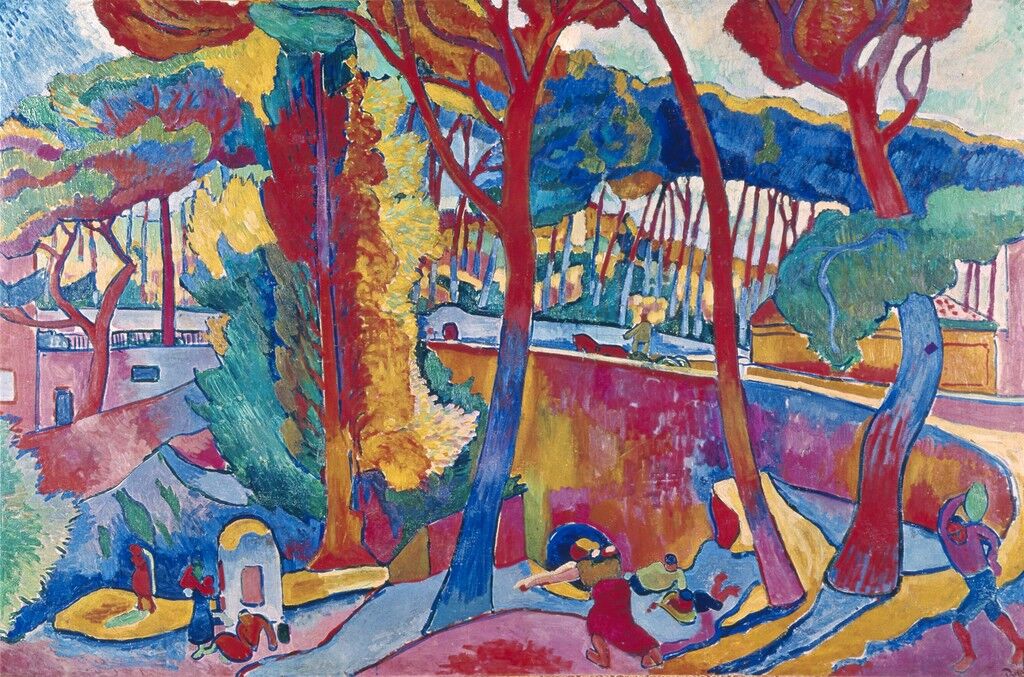

André DerainL'Estaque1905The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Before Cubism emerged as one of the most influential modern art movements of the 20th century, Fauvism made waves. And as with the later movement, the masses did not immediately take to Henri Matisse and André Derain’s unnatural approach to painting, nor did critics who were accustomed to artistic realism—particularly the critic Louis Vauxcelles. Fauvist paintings, with their shockingly unorthodox usage of vivid colors and rough brushstrokes, went on view for the first time at the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris.

In room seven of the Salon’s exhibition space at the Grand Palais, highly saturated works by Matisse, Derain, and fellow colorists Maurice de Vlaminck and Albert Marquet were displayed alongside a relatively tame, Renaissance-like bust that was placed in the center of the room. The resulting juxtaposition caused Vauxcelles to call the sculpture a “Donatello parmi les fauves”—an Old Master, like Donatello, amidst wild beasts. (The room was then unofficially re-named “la cage aux fauves.”)

Rather than take offense, Matisse, Derain, and their peers welcomed the comment—practicing the principle that all press is good press—and started calling themselves Fauvists. Soon afterwards, Fauvism became all the rage in avant-garde Paris, only to be overshadowed by Cubism a few years later.

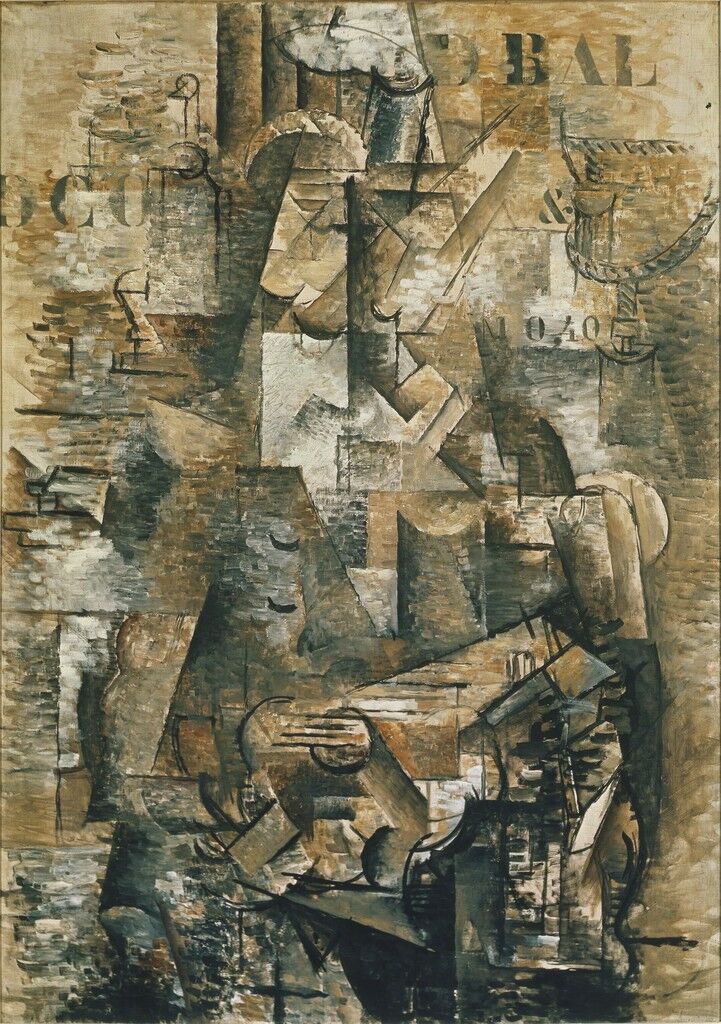

Georges BraqueThe Portuguese1911Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel

As so often is the case with groundbreaking cultural innovations—like rock and roll—this revolutionary art movement, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early 20th century, was initially challenged by contemporary critics. The artists threw perspective out the window, dissolving spatial borders, abandoning any vestige of naturalistic representation, and flattening the picture plane. Cubists were interested in depicting everyday scenes from multiple sharp angles, resulting in jumbled, geometric compositions—and it was this angular style that earned the movement its name.

Braque, influenced by Picasso’s distorted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907),incorporated similarly jagged, cubic and cylindrical shapes in his 1908 landscape Trees at L’Estaque. The painting was included in an exhibition of the artist’s recent work, held at the Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler Gallery in Paris that November, in what is now considered the first-ever display of Cubist art. One visitor happened to be the same critic that gave Fauvism its name, Louis Vauxcelles, who, unimpressed with Braque’s reduction of a lovely French landscape to simple shapes, wrote the following year of the artist’s “bizarreries cubiques,” or “cubic weirdness.” (According to some sources, Vauxcelles may have taken the word from another artist he once insulted, Matisse, who allegedly used it early on to criticize Picasso.)

Though intended as a jab—and Picasso or Braque were reportedly not thrilled with it—“Cubism” eventually stuck, and was cemented as the movement’s official moniker in Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes’s 1912 essay Du Cubisme. And just as he did with Fauvism, Vauxcelles had unintentionally coined the name for a strange new artistic development that he didn’t even like.

Sonia Delaunay and two friends in Robert Delaunay's studio, rue des Grands-Augustins, Paris 1924. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Courtesy of Tate Modern.

The term “Orphism” was coined by French poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1912, when he described Robert Delaunay’s “Windows” series at Paris’s Salon de la Section d’Or as “orphique.” Apollinaire was referencing the ancient myth of Orpheus, the Greek prophet known for his divine musical talents, and who had served as inspiration for many artists who were interested in the musical qualities of painting. In doing so, Apollinaire had connected the works of Delaunay and his wife, Sonia Delaunay, with those of painters like František Kupka, Jean Metzinger, Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, and Marcel Duchamp. These artists’ paintings all possessed a rhythmic cadence and featured lush color palettes, at least in the pre-Dada days—Picabia stopped working in the Orphist mode by 1915, and Duchamp abandoned canvases entirely after 1918.

Orphism had a lot in common with Der Blaue Reiter, which in some ways can be considered its German counterpart: Both promoted abstraction, emphasized a rich use of color, and were inspired by music, and each began around 1912, eventually getting cut short in 1914 by World War I. However, Orphism was more of an ad hoc movement—it probably wouldn’t have existed, nor been included here, if not for the connections made by Apollinaire; it’s better understood as a loosely connected group of artists who shared similar ideas at the same time and who represented a key point on the road to wholly abstract art.

Today, the term is primarily associated with Kupka and the Delaunays, each of whom continued working in the Orphist style long after its heyday, for the remainder of their respective careers.

Unlike most other movements discussed here, whose names tend to have clear origins, the story behind the term “Dada” is rather ambiguous—though perhaps that’s the point. Dada embraced nonsense, irreverence, and the absurd; its members engaged in making “anti-art” as a reaction to World War I, and against the bourgeois society that caused it. The movement emerged in two locations almost simultaneously during the war: New York, where Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia were showing in proto-Dada exhibitions beginning in 1915; and in the neutral city of Zürich, where foreign poets and artists like Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp escaped from their war-ravaged nations and pursued this avant-garde rebellion.

In February, 1916, the group held its first meetings as the “Cabaret Voltaire,” formed by writer Hugo Ball and singer Emmy Hennings in the back room of a divey tavern. According to the Tate, Ball wrote in a magazine later that year that the group would now “bear the name ‘Dada.’ Dada, Dada, Dada, Dada, Dada.”

Still, it’s uncertain exactly who came up with the name: Another common tale is that German poet and psychoanalyst Richard Huelsenbeck threw a knife into a dictionary, which must have punctured the entry for dada, a colloquial French word for a hobby-horse. “Dada” may also have been strategically chosen for its simultaneous meaning in some languages—MoMA notes that it translates to “yes, yes” in Russian—and complete nonsense in others. For English speakers, it sounds like little more than a baby’s first words.

Regardless of who came up with it, Dada made the perfect name for the movement, what with its childish associations, international reach, and utter absurdity. It became official in 1918 with Tzara’s Dada Manifesto.

Theo and Nelly van Doesburg in the studio on Rue du Moulin Vert, Paris, 1923. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

This Amsterdam-based movement, known for its use of primary color palettes and straight-lined shapes, has an equally straightforward origin for its name. De Stijl adapted its moniker from a journal launched in 1917 by one of the movement’s leaders, painter and theoretician Theo van Doesburg. He and another founder, geometric abstraction icon Piet Mondrian, spread their ideas on harmony and clarity in art throughout interwar Holland via De Stijl magazine, which van Doesburg also edited.

De Stijl artists sought an ideal of balance—in art as in life—after the tragedies of World War I, and ultimately hoped their hyper-rational style would lead to a harmonious, functional, aesthetically pleasing world, and one characterized by greater moral clarity. As Mondrian wrote in an issue of De Stijl, such a “pure plastic vision should build a new society.” He initially dubbed these concepts “Neo-Plasticism,” a term still often used to refer to his own work. But De Stijl’s simple meaning—it’s Dutch for “the style”—made it even more apropos for the movement.

Walter GropiusBauhaus1925-1926The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, Dessau

Like many others in the aftermath of World War I, German architect Walter Gropius sought to reform his country’s defeated, anxiety-ridden society. In his case, this took the form of a school that he founded and named the Bauhaus (from the German words “bauen” and “haus,” roughly translating to “house of building”)—what he described, in his 1919 manifesto, as “a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist.” The word Bauhaus has roots in “Bauhütten,” which were medieval lodges used as shelters for stonemasons in Gothic Germany.

The Bauhaus School indeed eradicated the boundaries between structural and decorative arts during the late 19th century, and became a massively influential center for art, architecture, and design. Though the school’s location changed multiple times during its existence—from Weimar to Dessau and finally Berlin, where it was shuttered by the Nazis in 1933—its curriculum remained consistently strong and innovative. (It would later morph into the “New Bauhaus” school, directed by Bauhaus alumnus László Moholy-Nagy, in Chicago.)

With faculty members like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, Bauhaus’s focus on industrial design, hands-on workshop training, and emphasis on functionality produced not only a slew of iconic alumni—including Marcel Breuer, Anni and Josef Albers, and Herbert Bayer—but also an iconic movement in its own right.

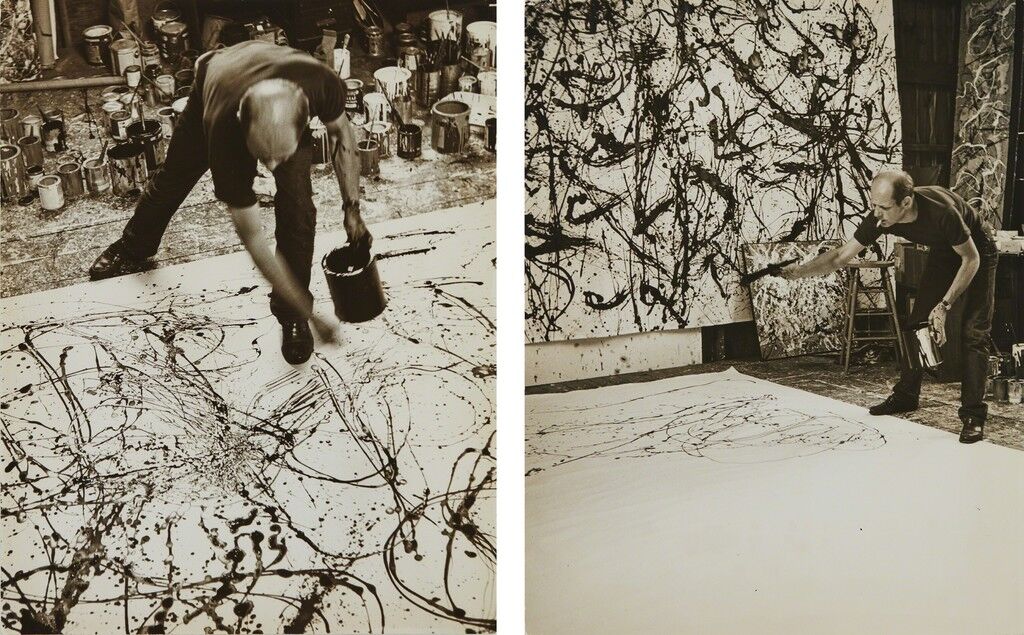

When art historians talk about Abstract Expressionism, they’re almost always referring to the famed post-war movement based in New York—but the term had actually existed decades before Jackson Pollock started dripping paint all over his canvases. It first appeared in an article on German Expressionism from 1919; 10 years later, inaugural MoMA director Alfred H. Barr Jr. used it to describe works by Wassily Kandinsky.

But it was American critic Robert M. Coates that introduced the phrase as we know it today; in 1946, he described Hans Hofmann’s messy, colorful paintings as Abstract Expressionist; he subsequently applied the term to the chaotic canvases of fellow New York dwellers Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

More a loosely-affiliated circle of artists than a movement, the Abstract Expressionists developed the distinct (yet parallel) modes of action painting and color field painting. It wasn’t until the early ’50s that any of these artists formally came together—to boycott a Metropolitan Museum of Artexhibition titled “American Painting Today—1950.” Pollock, de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and 14 other artists wrote a protest letter to the museum, attacking it for alleged bias against “modern painting.” The letter soon landed on the front page of the New York Times.

American media quickly grew fascinated with these bold painters, an interest that apexed with a 1951 profile in LIFE magazine that (literally) brought “Abstract Expressionism” to the nation’s doorsteps. It included a now-legendary ensemble photo of 15 artists who practiced the style.

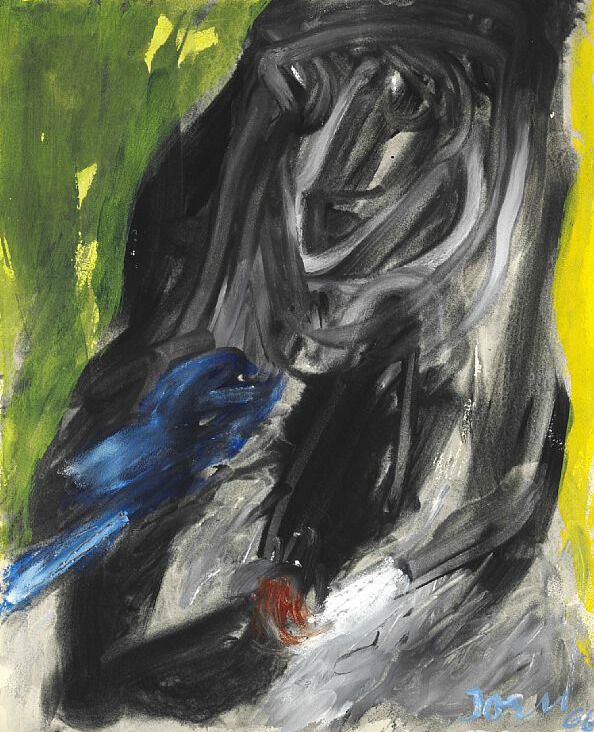

On November 8, 1948, the 25-year-old painter-slash-poet Christian Dotremont invited a group of artists from Denmark, Holland, and his native Belgium to meet him at a café in Paris. This wasn’t their first encounter, however. Dotrement, Asger Jorn, Karel Appel, Carl-Henning Pedersen, and the other attendees all knew one another, but from an earlier world—one before the devastations of World War II. This informal circle of artists had been temporarily broken during several years of Nazi rule, and by the time the war ended, “we wanted to start again, like a child,” as Appel once said.

That November evening saw the official formation of this continent-spanning group that came to be known as CoBrA: a portmanteau of its members’ home bases of Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. According to its manifesto, written by Dotremont shortly thereafter, the group chose to call itself “CoBrA” as “a tribute to the geographic passion which filled us in our refound freedom, giving birth to the animal myth.” (And they probably thought it sounded a lot cooler than “DeBeHo.”)

The CoBrA group spoke out against pre-war art movements such as Surrealism, and also rejected the geometric abstraction pioneered by De Stijl. In fact, the troubles of the war caused them to resent Western culture entirely and to turn to “primitive” cultures and children’s scribbles for inspiration. (“Primitive art” is a highly problematic term used in the late 19th and 20th centuries to mean, essentially, “non-Western art.”)

Though short-lived, CoBrA had a massive influence on a later generation of artists, and contributed to the development of the contemporary auction category called “Outsider art”—which itself was not coined as a term until 1972, and remains popular (yet understandably controversial) to this day.

Gutai, another post-war movement, was formed near Osaka, Japan, in 1954. Its name is usually translated into English as “concrete,” which reflects its followers’ aims of creating works of art with more than just a tube of paint—incorporating materials such as mud, chemicals, plastic, and Elmer’s glue. According to its entry in the Tate’s dictionary of art terms, Gutai has also been translated into English as “embodiment,” perhaps pointing to its ties with performance art, and also functioning as a double-entendre: For instance, Kazuo Shiraga’s “performance paintings,” which saw him dipping his feet in paint buckets or writhing, half-nude, in a pile of mud, can be understood as literal embodiments of putting brush to canvas.

Indeed, as Jiro Yoshihara, the movement’s co-founder and primary leader, wrote in its 1956 manifesto: “Gutai Art does not alter matter. Gutai Art imparts life to matter.” Gutai artists, including Shiraga, Atsuko Tanaka, and Saburo Murakami, experimented with new forms and media while also remaining inherently tied to painting; this set it apart from other performance-based, post-war movements, like Happenings, which totally abandoned any trace of the traditional art form. Further, Yoshihara himself was a self-taught painter, which likely explains Gutai’s continued connection to the medium even while artists pushed its limits.

Considered the first avant-garde Chinese art movement, the Stars Art Group (a.k.a. Xing Xing) emerged in Beijing during the late 1970s. Founded by Huang Rui and Ma Desheng in opposition to the state-promoted Socialist Realist art, the group grew to include like-minded artists such as Ai Weiwei, Li Shuang, and Wang Keping. These artists were mostly untrained and didn’t work in a particular style; rather, they created expressive works that commented on censorship and isolation in China. Primary examples include Wang’s bronze sculptures that satirized Mao Zedong, or Ai’s early Suzhou River in Shanghai (1979), in which the 22-year-old prodigy brought Pop artaesthetics to a traditional Chinese landscape.

As for its colorful name, Ma once explained that they called themselves the Stars “to emphasize our individuality. This was directed at the drab uniformity of the Cultural Revolution.” Indeed, the group’s first exhibition in September 1979—in which they hung their own artworks on railings outside of the state-controlled China Art Gallery (known today as the National Art Museum) in Beijing—was a protest against the Mao-instated rule mandating that public displays of art be approved by the government.

Authorities were quick to react, shutting the exhibition down after two days; in response, the Stars organized a march calling for democracy and artistic freedom. Their efforts proved successful: The group was allowed to re-stage the show in a different location, and it was said to have attracted over 80,000 viewers over 18 days. Despite this initial win, the government’s criticism and censorship of the Stars continued, and the group decided to split under political pressure in the early 1980s.

Afterwards, many of its members emigrated from China in search for greater freedoms, most notably Ai, who lived in the U.S. from 1981 to 1993 and is now based in Berlin, where he continues to use art as something of a political weapon—much in the spirit of the Stars.

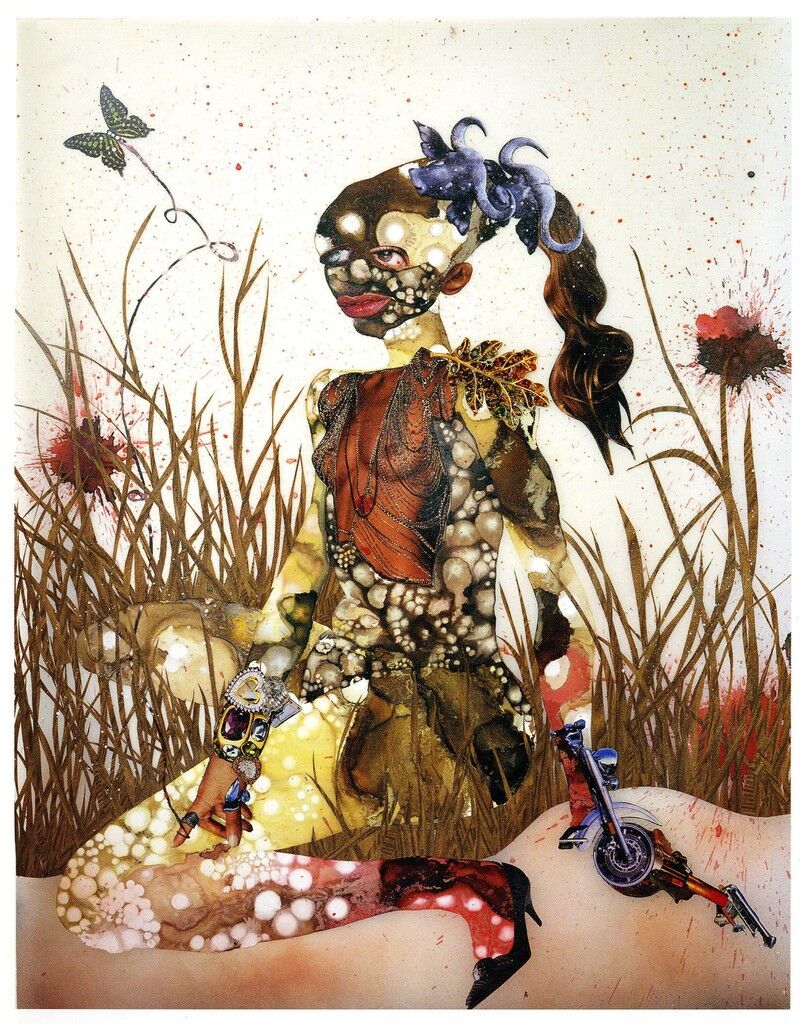

Spanning the fields of music, film, literature, and beyond, Afrofuturism is best defined as an Africanist movement to hypothesize, visualize, and understand black existence in a postmodern world. Early Afrofuturist works of the 1960s and ’70s, from Octavia E. Butler’s science fiction novels to Sun Ra’s cosmic jazz compositions, were informed as much by futuristic thinking and the aesthetics of the mid-century space age as by traditional arts of the African Diaspora.

Though its roots were planted in the mid-20th century, the movement’s name, “Afrofuturism,” wouldn’t emerge for a few decades. The term comes from the influential essay “Black to the Future,” first written by cultural critic Mark Dery in 1993 and published in the 1994 book Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. “Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th-century technoculture…might, for want of a better term, be called ‘Afrofuturism,’” wrote Dery. “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?”

The term Afrofuturism has since been applied to numerous visual artists of later generations—like Renee Cox and Wangechi Mutu—whose works draw upon Butler’s utopian writings and Sun Ra’s mystical persona, and engage with Dery’s existential questions about race, identity, and community. And a younger generation of artists including Juliana Huxtable, Jacolby Satterwhite, and Elia Alba continues to employ Afrofuturist aesthetics.

Kim Hart is an Editorial Intern at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment