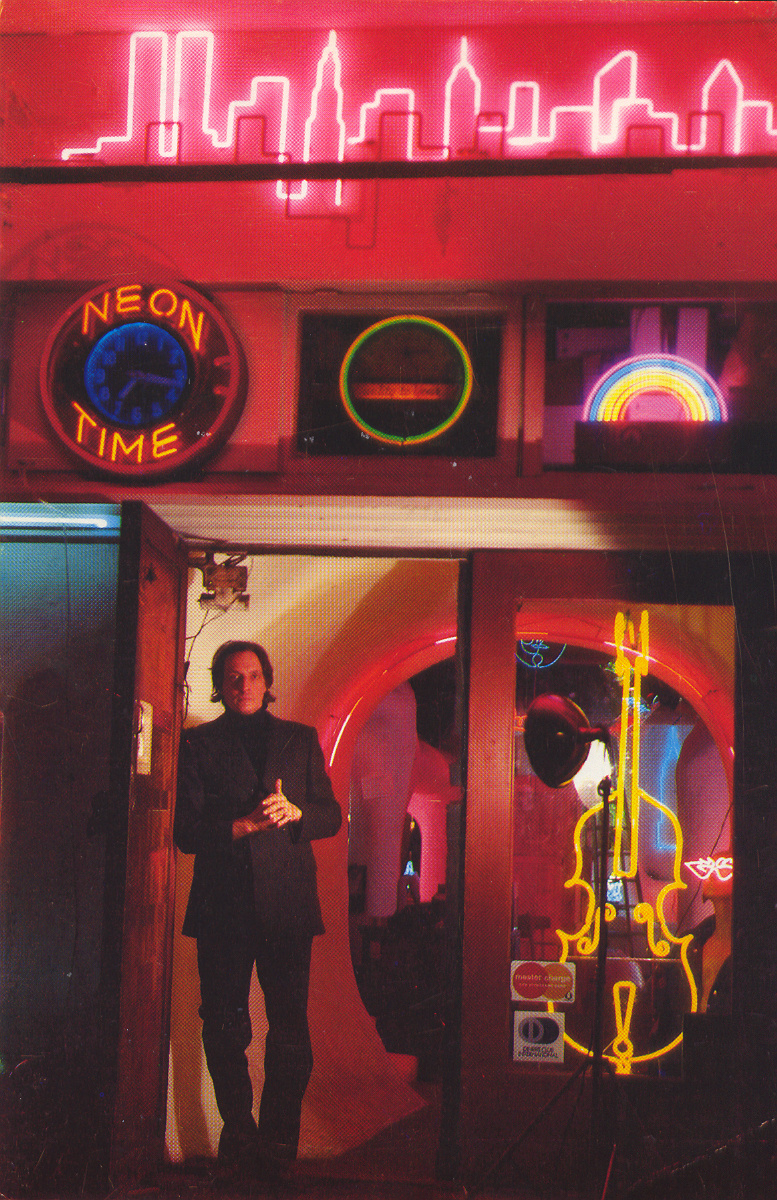

The Workshop Where Famous Artists Get Their Neons Made

- Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

On any given day along Tribeca’s White Street, you’ll find spellbound pedestrians gazing at a tangle of gas-filled, bent-glass tubes hanging outside Let There Be Neon, one of New York’s last surviving neon workshops.

Opened in 1972 as a means to make the medium more accessible, the shop is the go-to manufacturer for artists like Tracey Emin, Doug Wheeler, Philippe Parreno, and Martin Creed. Other items on the shop’s resume—from a pink truck-stop girl sign for The Sopranos to countless glowing and flickering BAR, PIZZA, and DINER signs for storefronts around the country—attest to the enduring influence of its late founder (and artist) Rudi Stern, who’s widely credited with reviving the craft of neon and revolutionizing its use in art and commerce.

Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

Courtesy of Let There Be Neon. Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

While Stern trained as a painter with Hans Hofmann and Oskar Kokoschka, his primary medium was light. In the 1960s, after earning a bachelor’s degree in studio arts from Bard College and a master’s degree from the University of Iowa, Stern moved to Manhattan, where he created psychedelic light shows for rock outfits like The Byrds, The Doors, and Timothy Leary. He designed installations for artist Laurie Anderson, signs for Broadway shows, and, as an early advocate of video art, co-founded an experimental video and performance space called Global Village in 1969. Stern soon developed a fascination with vintage neon signs, and set his loft ablaze with electric relics.

Neon has come a long way since its earliest days. Introduced by French engineer and chemist Georges Claude at the 1910 Paris Expo, the medium made its commercial debut at a Parisian barbershop in 1912, and was first used in the United States by the Packard car dealership in Los Angeles in 1923. After America’s prohibition laws were overturned, neon became a fittingly garish marker for boozing venues, and became synonymous with advertising and industry. But its popularity fell into decline during and after World War II, when cheaper fluorescent-lit plastic signs were more widely deployed.

Work by Keith Haring. Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

Work by Keith Haring. Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

Stern felt compelled to pursue not only his interest in neon, but also his sense of responsibility in preserving the medium. So he set about establishing a neon gallery, Let There Be Neon, where old neon signs were displayed and sold. And he soon discovered a viable business opportunity.

“Early on, Rudi made a brilliant discovery: he could offer people custom signs,” says Jeff Friedman, who joined Let There Be Neon in 1977 and became its owner in 1990. In the ’60s and ’70s, neon was finding its way into the realm of fine art in the form of sculptures by artists like Dan Flavin. (Argentine sculptor Gyula Košice was among the first artists to utilize the medium in the 1940s). But now, for the first time, anyone—not only artists—could have their vision realized in skillfully bent, luminous glass tubes.

“Rudi built a team that created this fresh new thing—artistic neon,” Friedman says. “It was unheard of!”

Friedman remembers the shop’s early work for New York’s Infinity Disco, the first dance club to feature neon as its primary light source, and Studio 54, where flashing, spinning neon panels descended from the ceiling as one of the space’s main lighting effects. Today, he maintains an increasingly diverse clientele: The day I visited, pieces for Chanel, WeWork, the High Line, Coach, and a cigar shop were in the works, while others in wood shipping crates were awaiting pick-up in front of the 3,500-square-foot space.

The shop recently completed a series of backlit runways for Wheeler’s immersive, soundless installation PSAD Synthetic Desert III (1971), currently on view at the Guggenheim.

Friedman waxes poetic about the artists he’s worked with, indicating the close, collaborative effort required for each piece. The shop began working with Emin nearly two decades ago, and now manufactures all her neon pieces for projects in North America. A 2012 artist’s proof of Emin’s The Kiss Was Beautiful (2013) is on permanent display in the storefront. “Tracey is very much responsible for the new popularity of neon, and for allowing people to have a different point of view about neon,” Friedman says, citing a growing trend of clients asking for neon signs that hang indoors.

- Tracey Emin, The Kiss Was Beautiful, 2013. Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

Working with artists requires the shop to both draw from its extensive knowledge bank and to continually innovate. With help from a chemist at a leading raw glass manufacturer, for example, it makes two custom colors exclusively for Wheeler. It frequently works with Iván Navarro, the Chilean-born, Brooklyn-based artist for whom it has created trippy infinity chambers and furniture silhouettes. Artist Curtis Kulig commissioned the shop to render his iconic “Love Me” tag and “Love Me” smiley in neon; it also manufactured Ugo Rondinone’s neon-lit Hell, Yes! sculpture (2001) that once hung on the New Museum’s facade.

Keith Haring, Robert Rauschenberg, Dennis Oppenheim, and John Lennon and Yoko Ono have all worked with the shop.

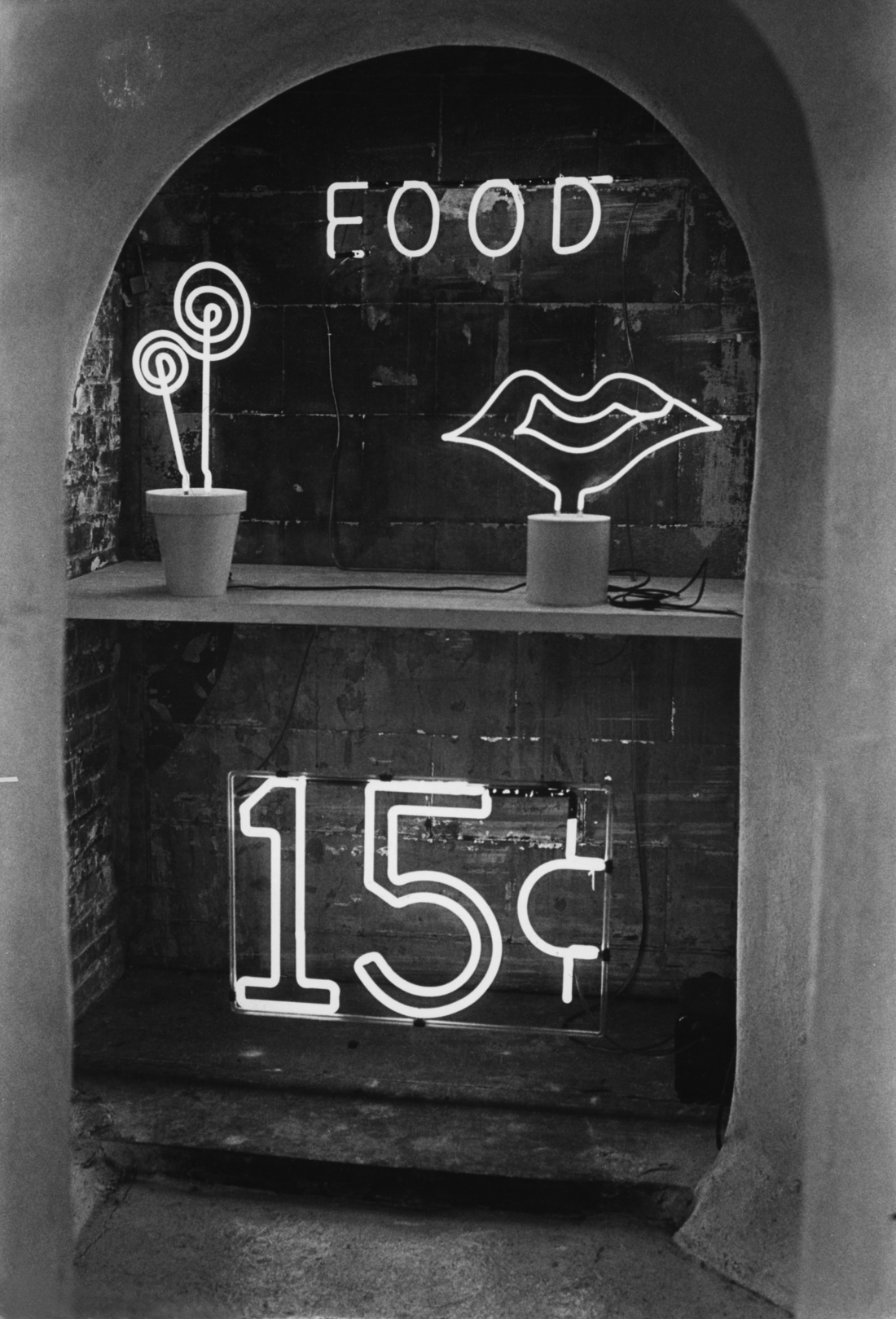

Neon has long toed the line between science and art: Even the simplest designs take multiple hands to create. Each project at Let There Be Neon is made on-site by a team of master glass benders, who work in shifts to ensure a constant chain of production. When the shop receives a file or drawing, it’s digitally tweaked and printed as a life-size pattern. The specs are then given to a glass bender, who uses an open flame to heat glass rods that come in a variety of colors. Once noodle-like, they’re twisted into shape and fused together. The glass is then purified and filled with gas: either neon, which is red, or argon, which is blue.

Work by Ivan Navarro. Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

Work by Ivan Navarro. Courtesy of Let There Be Neon.

“So if you take a blue tube and put red gas inside, you get pink,” Friedman says. “It’s like mixing watercolors with light.” Electrodes on each tube allow an electrical current to flow through it when turned on, exciting the molecules inside and producing light.

“Our work with artists is totally different [than working with commercial clients],” Friedman says. “But it helps us, too.” He recalls working with Olafur Eliasson on his Daylight Map (2005), in which a series of neon tubes, overlaying a world time zone map, fade from light to dark according to where daylight exists at a given time. Its complexity required extra attention from the shop’s engineers and computer programmer, who made Eliasson’s concept a reality with the help of a clock, sequencer, and transformer placed in each tube.

“It was crazy,” Friedman says. “But that knowledge is part of our DNA now—that’s how the circle works.”

One of the shop’s veteran glass benders, Ed Skrypa, told me the neon-making process hasn’t changed in one hundred years. Stern’s unbridled vision for neon is similarly enduring. “Rudi always said, ‘Neon is like drawing with light,’” Friedman says. “It’s a beautiful visual, isn’t it?”

—Tiffany Jow

No comments:

Post a Comment