These Photographers Quit Their Day Jobs to Travel the World

Theron

Humphrey was shooting handbags and sweaters for a clothing company in

Idaho when he realized he needed a change. Overworked and uninspired, he

decided to quit and, after some soul-searching, stumbled on a wild

idea: to drive across America and meet and photograph a new person each

day for an entire year. So in August 2011, he set off in his pickup

truck with Maddie, his now Instagram-famous coonhound, and made his way

through all 50 states—even Hawaii—to capture and collect the unique

personal histories of 365 strangers.

Today, Humphrey has a loyal Instagram following of 1.2 million, a published book on his trusty companion, Maddie on Things, and a self-made career that he can take pride in. While it’s no doubt a risky move to leave a stable income, several others have made a similar leap of faith: They quit their jobs, packed their bags, and set off on adventures around the world, pursuing new walks of life that culminated in beautiful works of art. Below, we highlight eight photographers—from living legends, like Sebastião Salgado, to free-spirited nomad Foster Huntington—who’ve quit their day jobs for the thrill of an unknown future.

Today, Humphrey has a loyal Instagram following of 1.2 million, a published book on his trusty companion, Maddie on Things, and a self-made career that he can take pride in. While it’s no doubt a risky move to leave a stable income, several others have made a similar leap of faith: They quit their jobs, packed their bags, and set off on adventures around the world, pursuing new walks of life that culminated in beautiful works of art. Below, we highlight eight photographers—from living legends, like Sebastião Salgado, to free-spirited nomad Foster Huntington—who’ve quit their day jobs for the thrill of an unknown future.

In

1973, while sitting in a rowboat with his wife Lélia and working as an

economist in London, Salgado made the life-changing decision to quit his

job and pursue a newfound passion: photography. In the years prior,

Salgado had made frequent trips to countries in central and east Africa

to help initiate agricultural development projects for the World

Bank—and each time he brought along a Pentax Spotmatic II with a 50-mm

lens, a gift from his wife that had sparked an unanticipated obsession.

Now a world-renowned social documentary photographer, Salgado never

entirely parted ways with his background in economics. “When you go to a

country, you must know a little bit of the economy of this country, of

the social movements, of the conflicts, of the history of this

country—you must be part of it,” he has said.

This desire to understand, and thereby to honor, his subjects is

reflected in Salgado’s award-winning black-and-white documentary

series—including “Workers, “Migrations,” and most recently,

“Genesis”—which shed light on issues of poverty, oppression, and climate

change threatening displaced communities around the world.

Though Drake had never conceived of being a photographer growing up, she realized

in adulthood that “success is what you want it to be.” About a decade

ago, Drake left her New York office job at a multimedia company to

travel on a Fulbright scholarship to Ukraine, where she began to create

photo stories fueled by her interest in Russian, Islamic, and Chinese

cultures. “I was about 30 and I realized I didn’t want to work in an

office for the rest of my life, in New York’s bubble,” she explained.

“I wanted to learn about the world and cross into other communities.”

Wielding her camera, she made some 20 trips to countries in Central Asia

over the next 6 years, which culminated in two celebrated projects: Two Rivers

(2007-11), an in-depth look at the struggling economies, shifting

borders, and environmental calamity in the region between the Amu Darya

and Syr Darya rivers; and Wild Pigeon (2007-13), a collection of

photographs, drawings, and embroideries produced collaboratively with

Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group in western China, whose cultural freedom

is threatened by rapid modernization.

Foster Huntington

As

a concept designer at Ralph Lauren in New York, Huntington “got turned

off of working in fashion and designing things for rich dudes in

Connecticut” and realized

that he “shouldn’t be inside an office building working 70 hours a week

in my early twenties for some big-ass corporation.” So he did what many

stifled employees want to do, but never actually end up doing—he left.

In the summer of 2011, Huntington quit his job, moved into a camper, and

drove some 100,000 miles around the West, surfing and camping along the

way and documenting his journey.

Since 2014, Huntington has been living in a tree house in southern

Washington, along the Columbia River Gorge, which he designed and built

with a group of friends. (Its construction is documented in his book and

short film, both titled The Cinder Cone.) Now with an Instagram

following of over 1 million, Huntington hopes to inspire others to take

up his nomadic lifestyle—to see the world without relying on creature

comforts along the way.

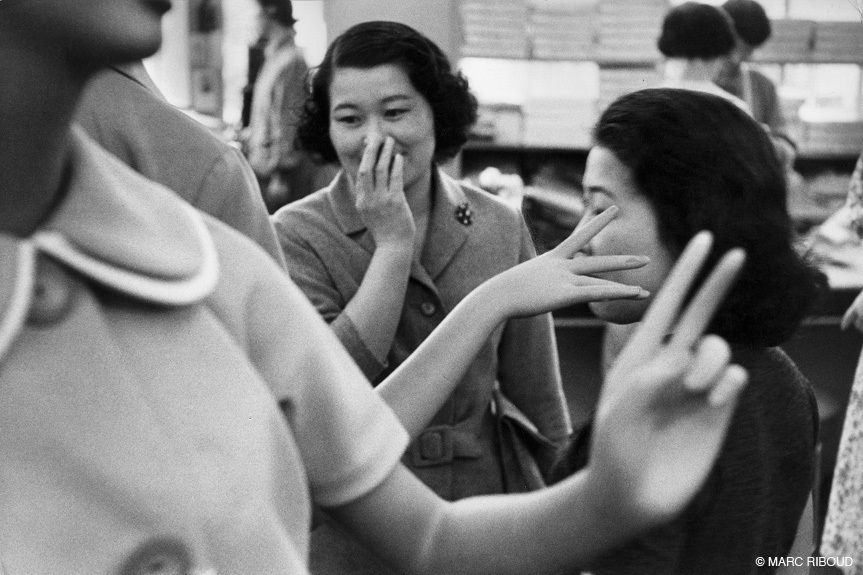

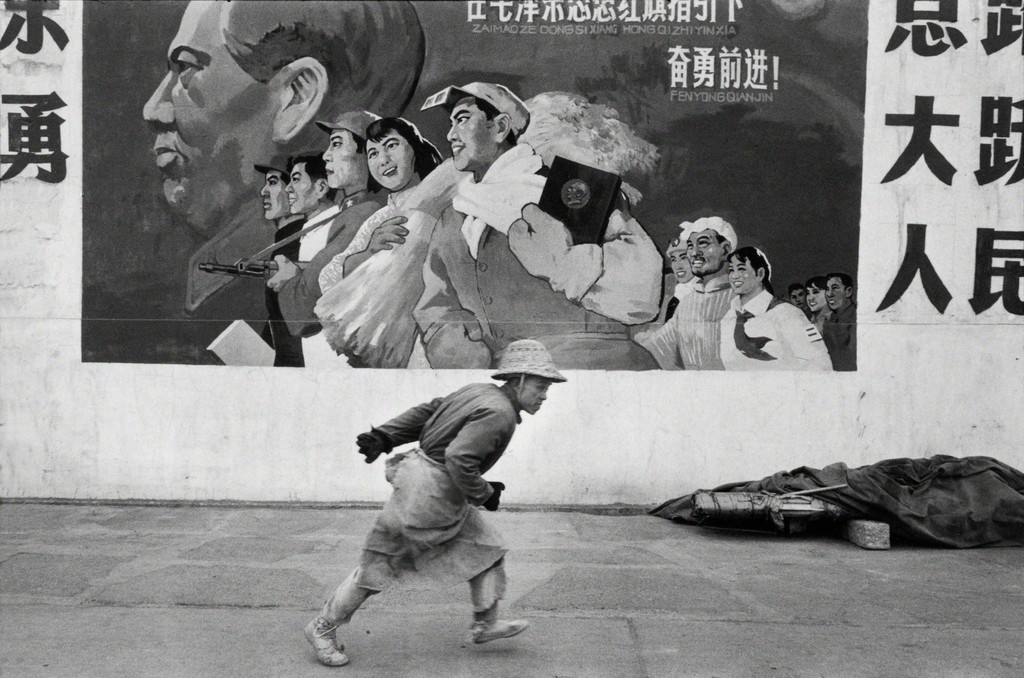

As a teenager—a self-described

“rebel” who later fought in the French Résistance—Riboud took his first

photographs at the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1937 using the

Vest Pocket Kodak camera his father had gifted him for his 14th

birthday. But it wasn’t until the early 1950s, while on vacation and

photographing a festival in his hometown of Lyon, that he decided to

quit his job as an engineer at a factory, where he admitted he had

“spent a lot of time dreaming of other things and taking pictures on

weekends.” Starting off as a freelance photojournalist, he befriended Henri Cartier-Bresson and, in 1953, was accepted into Magnum—the same year his famous Eiffel Tower Painter photograph was published in LIFE. A fiercely independent spirit, and intimidated by the likes of Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa,

and David “Chim” Seymour, he promptly left France for two years—setting

off a career marked by international travel, most famously to the Near

and Far East. In these now-iconic photographs of civilians on the

streets of Mao-era China and the Vietnam War, Riboud captured quiet,

intimate moments amidst important historical events.

Boston-born

photographer Nickerson worked as a commercial fashion photographer for

the first 15 years of her career, shooting for Vanity Fair and Vogue, among other high-profile clients. Exhausted and disenchanted, she has recalled

thinking, “You’re wasting your life. If you want to do photography,

you’ve got to rethink this whole thing.” So when she accompanied her

friend on a visit to a farm in Zimbabwe in 1997, she became enamored by

the rural landscape and started to use photography as a means of

acquainting herself with local residents. A trip that was supposed to be

a few weeks long stretched into four years—and a new career. “I bought a

small flatbed truck and started to travel all around the country and

then went to South Africa, Malawi, and Mozambique. I took pictures of

everything,” she told TIME. Since then, she hasn’t stopped

traversing the globe, venturing back to Sub-Saharan Africa for portraits

of faceless farm laborers in her 2013 series, Terrain. Even in

recent forays back into fashion, the influence of these efforts is

clear, with the statuesque figures swathed in layers in a 2014 AnOther spread echoing the fashion and rural environs of Terrain. In the same year, Nickerson photographed four of the five Ebola Fighters covers for TIME—becoming the first woman to shoot the Person of the Year in the 87-year history of the magazine.

“It’s too late” is a mentality that sometimes impedes middle-agers from changing careers—but Canadian photographer Michael Levin

was never one to turn down a challenge. Though he had a keen eye since

childhood—“always looking at an interesting rock rather than a landmark”

on family trips—he found himself working as a restaurateur. Five years

later, Levin sold his business and picked up a camera at the age of 35.

He began by shooting stunningly spare black-and-white landscapes

inspired by Mark Rothko and Michael Kenna,

first around his home city, Vancouver, and then around the world—in

France and England, and later Iceland, South Korea, and Japan. He

attributes his marketing chops to his former career. “My job is to

promote my work as much as possible. That’s the reason that the work is

successful,” he once said. To aspiring photographers, he insists

that going full-time is “absolutely possible” if you recognize that

talent alone won’t cut it: “There are so many great photographs being

taken but you have to pursue ways to elevate your work and gain broader

exposure for it.”

In

1962, the now-legendary street photographer Meyerowitz was working as

an art director at an ad agency earning the equivalent of $29,000 per

week. After supervising a publicity shoot with photographer Robert Frank, the 24-year-old Meyerowitz walked around New York as if, he recalled in 2012,

he “was reading the text of the street in a way that I never had

before.” From there, Meyerowitz picked up his camera and began

hitchhiking around the American South and Mexico with his first wife,

his initial foray into the many trips he would take by road in the 1960s

and ’70s. Later, the photographer felt an impulse to “get away from my

familiar tactics and my familiar understanding of the American system,

the American way of life, to see what the rest of the world looked like

and what it would teach me about myself,” as he has explained.

In 1966, with his cherished Leica in hand, Meyerowitz embarked yet

again, this time on a year-long road trip across Europe. He began in

London and made his way across the continent—from France and Spain to

Greece and Italy, with several stops along the way—shooting “life along

the roadside whizzing by at 60 miles per hour.” These iconic

black-and-white photos led to his first show at MoMA in 1968, curated by

photography legend John Szarkowski.

Theron Humphrey

In

2011, North Carolina-born photographer Humphrey, having raised $16,000

on Kickstarter to pursue his wild idea, set off on his journey,

uploading images one by one to his website. En route, his project

evolved: He added an audio component, recording people’s voices, and

started an Instagram account. This was a drastic change from his life

just a few years earlier. On shooting product for a women’s retail

company, and not for himself, he once said,

“you start to lose your creative soul. There is a balance, and you need

to feed yourself, but if you’re only using your camera to shoot someone

else’s vision, it destroys you creatively.” Humphrey’s decision paid

off—he was named a Traveler of the Year by National Geographic in

2012. His advice to aspiring photographers is to “make work that isn’t

easy, that makes you feel uncomfortable, and make a lot of it….The slow

process of investing your time into a single idea is the greatest path.”

—Demie Kim

—Demie Kim

No comments:

Post a Comment