What Artists Should Do to Protect Their Legacies before Dying

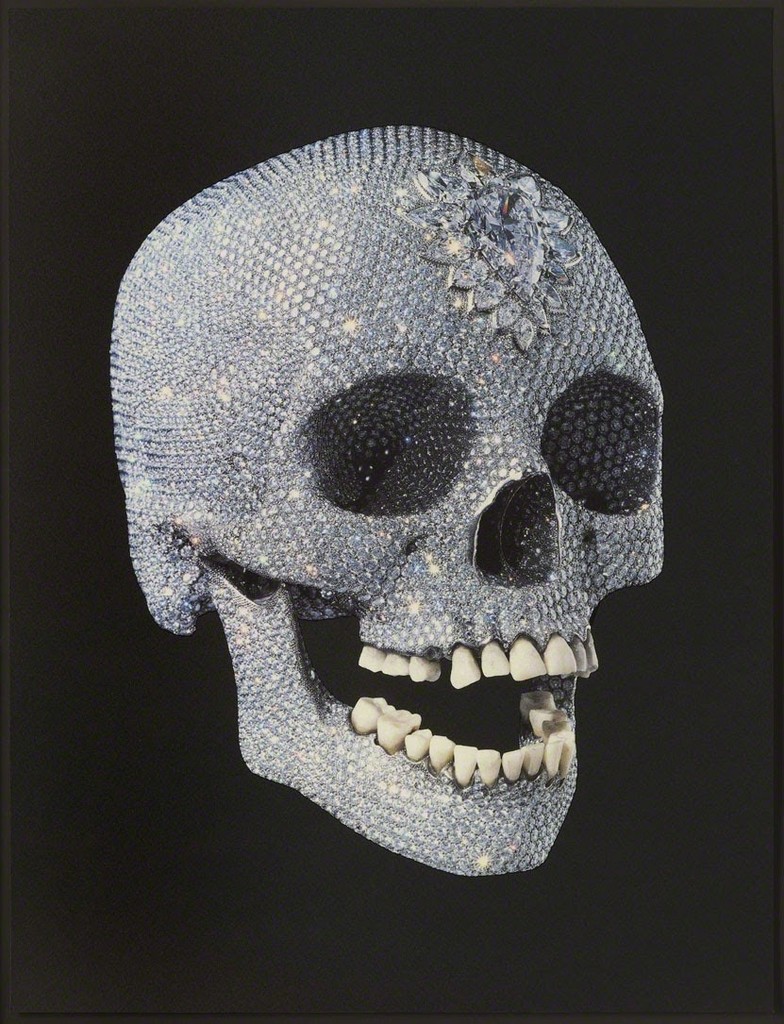

Art often makes viewers ponder their mortality. Just think of the memento mori,

a Latin phrase that translates directly to “remember you must die” and

refers to symbols of death in art, most typically skulls (hey, no one

said it should be subtle). And yet artists, as much as viewers, must

think about what happens after they die: how their work will be seen,

treated, and exhibited posthumously. Too often, the planning of artist

estates, the organizations that safeguard artists’ legacies, is treated

either as a straightforward legal exercise or one that can endlessly be

put off until old age.

But Loretta Würtenberger, co-founder of the newly launched The Institute for Artists’ Estates, cautions against such procrastination. Würtenberger, whose recently published book Artist Estate: A Handbook for Artists, Executors, and Heirs tackles the subject, spoke to us about what artists can do to ensure that their legacies are protected, and why estate planning is about more than signing a will (though that is important). Here are three steps that will help you protect your life’s work.

Artists frequently die before having organized their work, creating both difficulty in ascertaining how to distribute the pieces (to heirs, museums, etc.) and also allowing for the possibility of authenticity disputes. Creating a catalogue is something artists should avoid leaving to their senior years, according to Würtenberger. “The more specific thoughts an artist develops during their lifetime, the easier it is later,” she says, citing a recent conversation she had with an artist in his late forties who is represented by a large gallery and produces very technical art. “He is asking us to structure the whole question of a database for his studio.” That database will become a resource for questions of authenticity as well as serving as a repository for the artist’s technical know-how—something that’s useful even while the artist is alive. “It’s interesting how somebody of our generation is already thinking about the posthumous phase,” she says, “and how these thoughts have consequences for what he’s doing today.”

This is but one example of how the process of outlining your estate can affect the work you are producing, prompting you to think about how your materials will be preserved and how to categorize different pieces. Increased organization can also be beneficial to an artist’s market. Würtenberger points to Gerhard Richter’s website, which, though not a catalogue raisonné, provides “really good documentation of his oeuvre” and is accessible to everyone. “I believe it’s one of the reasons why there is such a stable market [for his work] and not too many forgeries,” she says.

Würtenberger conducted more than 50 interviews with artists, executors, and heirs for her forthcoming book, and during each one she asked what would have helped most in running the estate. “Every single heir, when there was not a will, said ‘I had wished there was a will,’” Würtenberger told me. The reasons are straightforward: A will spells out what the artist wanted, including how responsibilities and property are to be divided up and the way in which work should be presented. Should a certain amount of work go to a museum? Should it all be sold? Should none of it be sold? Who’s in charge of the distribution? The queries go on.

A fact that should surprise exactly no one is that being a great artist doesn’t necessarily mean that you are a gifted estate planner. Würtenberger points to no less than Pablo Picasso as a prime example of how not to plan your estate. “Picasso is the most prominent example of where there wasn’t a will,” Würtenberger says. “He was always afraid that the moment he would make a will, he would die the next day.” When Picasso did die in 1973, he left more than 45,000 works, millions in cash and gold, and an estate some believed was worth billions—but no will. It took six contentious years to divide everything up. Picasso had a reputation that endured, but keeping art and archives locked away as posthumous battles rage on can be damaging to an artist’s legacy.

All that said, artists’ estates and legacies hinge on more than just creating a will that solves everything lickity split. While the outcome of creating an estate—through a will or a foundation—is ultimately legal, the process of arriving there often isn’t. “Around 80 percent of the work is non-legal,” Würtenberger says. “It’s really questioning the essence of your oeuvre.” Sure, deciding you want your children to handle the foundation will ultimately be enshrined in a legal document, but getting there involves, as Würtenberger explains, “questioning your relationship to your children, questioning if you want them to do posthumous work—or do you want your widow [or surviving spouse] to it?”

And ultimately, she says, “it’s questioning yourself, your mortality.” So for all the practical aspects that go into an artist estate, the questions that artists must confront when creating them may not be all that different from the questions they face when producing their work in the first place.

—Isaac Kaplan

But Loretta Würtenberger, co-founder of the newly launched The Institute for Artists’ Estates, cautions against such procrastination. Würtenberger, whose recently published book Artist Estate: A Handbook for Artists, Executors, and Heirs tackles the subject, spoke to us about what artists can do to ensure that their legacies are protected, and why estate planning is about more than signing a will (though that is important). Here are three steps that will help you protect your life’s work.

Start Thinking about Planning Your Estate Now

Artists frequently die before having organized their work, creating both difficulty in ascertaining how to distribute the pieces (to heirs, museums, etc.) and also allowing for the possibility of authenticity disputes. Creating a catalogue is something artists should avoid leaving to their senior years, according to Würtenberger. “The more specific thoughts an artist develops during their lifetime, the easier it is later,” she says, citing a recent conversation she had with an artist in his late forties who is represented by a large gallery and produces very technical art. “He is asking us to structure the whole question of a database for his studio.” That database will become a resource for questions of authenticity as well as serving as a repository for the artist’s technical know-how—something that’s useful even while the artist is alive. “It’s interesting how somebody of our generation is already thinking about the posthumous phase,” she says, “and how these thoughts have consequences for what he’s doing today.”

This is but one example of how the process of outlining your estate can affect the work you are producing, prompting you to think about how your materials will be preserved and how to categorize different pieces. Increased organization can also be beneficial to an artist’s market. Würtenberger points to Gerhard Richter’s website, which, though not a catalogue raisonné, provides “really good documentation of his oeuvre” and is accessible to everyone. “I believe it’s one of the reasons why there is such a stable market [for his work] and not too many forgeries,” she says.

Picasso Died without a Will—Don’t Make the Same Mistake

Würtenberger conducted more than 50 interviews with artists, executors, and heirs for her forthcoming book, and during each one she asked what would have helped most in running the estate. “Every single heir, when there was not a will, said ‘I had wished there was a will,’” Würtenberger told me. The reasons are straightforward: A will spells out what the artist wanted, including how responsibilities and property are to be divided up and the way in which work should be presented. Should a certain amount of work go to a museum? Should it all be sold? Should none of it be sold? Who’s in charge of the distribution? The queries go on.

A fact that should surprise exactly no one is that being a great artist doesn’t necessarily mean that you are a gifted estate planner. Würtenberger points to no less than Pablo Picasso as a prime example of how not to plan your estate. “Picasso is the most prominent example of where there wasn’t a will,” Würtenberger says. “He was always afraid that the moment he would make a will, he would die the next day.” When Picasso did die in 1973, he left more than 45,000 works, millions in cash and gold, and an estate some believed was worth billions—but no will. It took six contentious years to divide everything up. Picasso had a reputation that endured, but keeping art and archives locked away as posthumous battles rage on can be damaging to an artist’s legacy.

Ask Yourself the Tough Questions

All that said, artists’ estates and legacies hinge on more than just creating a will that solves everything lickity split. While the outcome of creating an estate—through a will or a foundation—is ultimately legal, the process of arriving there often isn’t. “Around 80 percent of the work is non-legal,” Würtenberger says. “It’s really questioning the essence of your oeuvre.” Sure, deciding you want your children to handle the foundation will ultimately be enshrined in a legal document, but getting there involves, as Würtenberger explains, “questioning your relationship to your children, questioning if you want them to do posthumous work—or do you want your widow [or surviving spouse] to it?”

And ultimately, she says, “it’s questioning yourself, your mortality.” So for all the practical aspects that go into an artist estate, the questions that artists must confront when creating them may not be all that different from the questions they face when producing their work in the first place.

—Isaac Kaplan

No comments:

Post a Comment