Steven Klein: “It can get a bit mundane and boring.”

| 12:18 (há 22 minutos) |   | ||

| ||||

|

STEVEN KLEIN: DARK MATTERS

Steven Klein, Self-Portrait

Andrea Blanch: Congratulations on your book, I think it's brilliant.

Steven Klein: Thank you.

Andrea: Why did you decide to publish this now?

I THINK THAT WHEN EVERYTHING IS TOO PLACID AND QUIET IN THE PICTURE, I THINK IT CAN GET A BIT MUNDANE AND BORING

Steven: So, two reasons. I've tried to publish many books, unsuccessfully, in the past with different publishers because of disagreements or it not being the right time. Now is the right time because of several reasons. The work is more relevant. Secondly, most of the work that I did in this book feels like images I can't do right now for so many magazines and publications that I did in the past because some of them wouldn't be acceptable or considered offensive or a lot of the people that I've worked with, editors-in-chief and editors, Vogue and many other publications, are no longer there. So it's a time period that's ended. Not to say that new work isn't coming now or in the future, but I felt like it was the end of a period for me. There aren’t as many platforms or places where I could do these images as before. Of course, I can do anything for myself and continue to do that. As far as magazines and the kind of advertisement that's upon us- of diversity and inclusiveness and not being offensive to anybody-, it limits the idea of creativity with people.

Andrea: Why do you think your work is relevant today?

Steven: There's a historical part of photography because it depicts a certain period of time in my work over several decades. It’s also relevant because of the notion of the thread of, what Mark Colburn describes as, a violence. What really got me hooked on doing the book with Mark is that he was the first person that identified some of the themes in my work. For me, it was always fictional, but the idea of this underlying violence that’s prevalent in the world we live in today depicts not an idealistic world of advertising or types of fashion pictures, but some things that depict more real topics.

Andrea: What is a thread that runs through your work from when you’ve started?

Steven Klein, Girl in Lace Dress, New York City, 1996; Courtesy of Phaidon

Steven: The thing is, I haven't examined them from the beginning. From having a background of painting, sculpture, fine arts and photography, you put those together and that's part of who I am. I think that my work definitely changed circa Fight Club with Brad Pitt because I started working more with cinema and working with Franca Sozzani. She influenced me to work more cinematically because she saw that potential in me. Before, I was working more in a photographic two dimensional way, but when the cinema aspect came into play, it really helped formulate my vision.

Andrea: So, about Mark, has he always been an art director or a creative director?

Steven: He's not an art director. He's edited a lot of books. He did Mark Colbun, a lot of Lucian Freud's painting books, Nan Goldin's first book, Issey Miyake, and several books for Mapplethrope and Irving Penn. He's much more of an academic person. Having worked with people in the fashion business beforehand, I wouldn't call him an art director. He is more of an editor. I found that he was the right person to collaborate with on the edit of the book.

Andrea: Why did you segway from painting into photography and the fashion world?

Steven: I think two things: studying painting and realizing that I wasn't a very good painter. And I needed to make a living. I thought that doing this work, it wasn't like a life-changing, one day I decided to do this, but I definitely thought that this was a way to generate money, make a living, rather than being a painter and working alone.

Andrea: I was a painter before I became a photographer as well.

Steven: Oh, so you understand the painting to photography transition.

Andrea: Are you still friendly with people from RISD? I find that a lot of people that have gone to RISD keep in touch with people that have been in their class.

Steven: Some people I lost touch with over the last few years. With COVID, I lost touch with most people. I'm just starting to get acclimated with even my closest friends in New York. A lot of people I did get disconnected with over COVID.

Andrea: Well, everybody loves you.

Steven: How do you know that?

Andrea: They do. Everybody says the nicest things about you.

Steven: That's very nice to hear. I didn't know that. I try to be respectful and nice to everybody that I work with.

Andrea: I'm very curious- you say one of your artistic influences is Pablo Picasso?

BUT THE THING IS, IF I DON'T FEEL SOMETHING, I DON'T DO IT

Steven: Well, Picasso was the first thing that caught my eye during my first trip to New York. I went to the MoMA and saw Guernica, which was the first big painting I saw of Picasso’s. It was very interesting and I spoke about it in a talk I did in London. I think that it was a very interesting painting to see the scale, I had never seen anything that big. I became really interested in his paintings, cubism and the idea of abstract expressionism. For what reason, I can't give you, but that was the first thing that caught my eye. From that first visit to the MoMA.

Andrea: Have you used any of those influences in your work?

Steven: No, I think, because I started out in pottery, ceramics, glass blowing, lithography, and etching. I explored so many different disciplines. I did things with fabric and batik and all different types of things. And they weren't so much lithography when I did it. I did it for a period. I never did anything for short periods of time. So if I did lithography, I took it seriously. What was interesting about reading about and understanding Picasso, for me, was the idea that his life was his work. And that he did so many different types of work in so many different types of media. At that time, it was very unusual that he did ceramics as he also did sculpture, he did painting, he did photography, he did etching. I was very inspired by all the disciplines that he worked in.

Andrea: You've worked with the most popular of our cultural icons– Madonna, Brad Pit, Kate Morris, Angelina Jolie. How have your collaborations influenced your creative vision?

Steven: Each person I have a different relationship with. For instance, each person starts out with a certain problem that needs to be solved, and each project isn't so much like “okay, this is what I want to do,” and I just do it. There's a seed level of where things begin. The first project I did with Madonna, I had only met her, we'd never worked together. Since then, we've been collaborating for over 20 years. Our first collaboration was the idea of how I saw her solely as a performance artist. I built this environment like her studio or her testing grounds for her to execute her projects. Needless to say, I didn't know how much she rehearsed at that time or how much preparation she did for her work. From then, I did a lot of video pieces with her. I did a video installation at Deitch and then she asked me to do a lot of video pieces for her world tours, her opening, and then many of her videos thereafter, many shows. So she really began my film career. Brad was a different thing because I'd worked with Brad Pitt on some commercial projects over 20 years ago. Then, Brad called me when he was doing Fight Club. He loved the costumes from the movie. So he said, “Well, let's do something with the clothes.” I called Dennis Friedman and Dennis responded to do this story with Brad, because I think they would do a male actor once a year, but they never did a male actor in costume. It was always a credit that we broke that rule. Then I read the book, Fight Club, and Brad was finishing the movie and I created my idea of what Fight Club was in my mind. So every project has a different backstory. With Brad and Angelina, it was when they just finished the movie and Brad wanted to do publicity for the movie, but it was also the beginning of their relationship. Those pictures were at the very beginning of that. So the assignment was to do pictures to promote Mr. And Mrs. Smith, but it turned out to be more like a projection onto their lives ahead.

Andrea: Let’s talk about the shoot with Madonna, the one where she’s doing yoga. I'm curious because your shootings seem very controlled in a good way. Is there room for any spontaneity while you're on set shooting?

Steven: I have a framework, like a storyboard or a script, but that doesn't mean that it’s a rigid script. I don't work on a rigid script at all. The thing is, it's always collaborative. I kind of dislike when people say a yoga pose because the thing is I see it more as Muybridge, I don't know if you're familiar with Muybridge’s contortionist. I had an actual piece of the contortion set. As a performance artist, she was doing yoga at the time, which probably allowed her to do that pose, but I see it more as a contortion. With that picture, I don't think I had that pose and that exact picture in my mind or had it story boarded like that. There were pictures that were depicted in that story that were story boarded. Some things are very exact, led the way I draw them or the way I reference them, and then some take a life on their own. But I always do like to have a storyboard and a structure before going into a project.

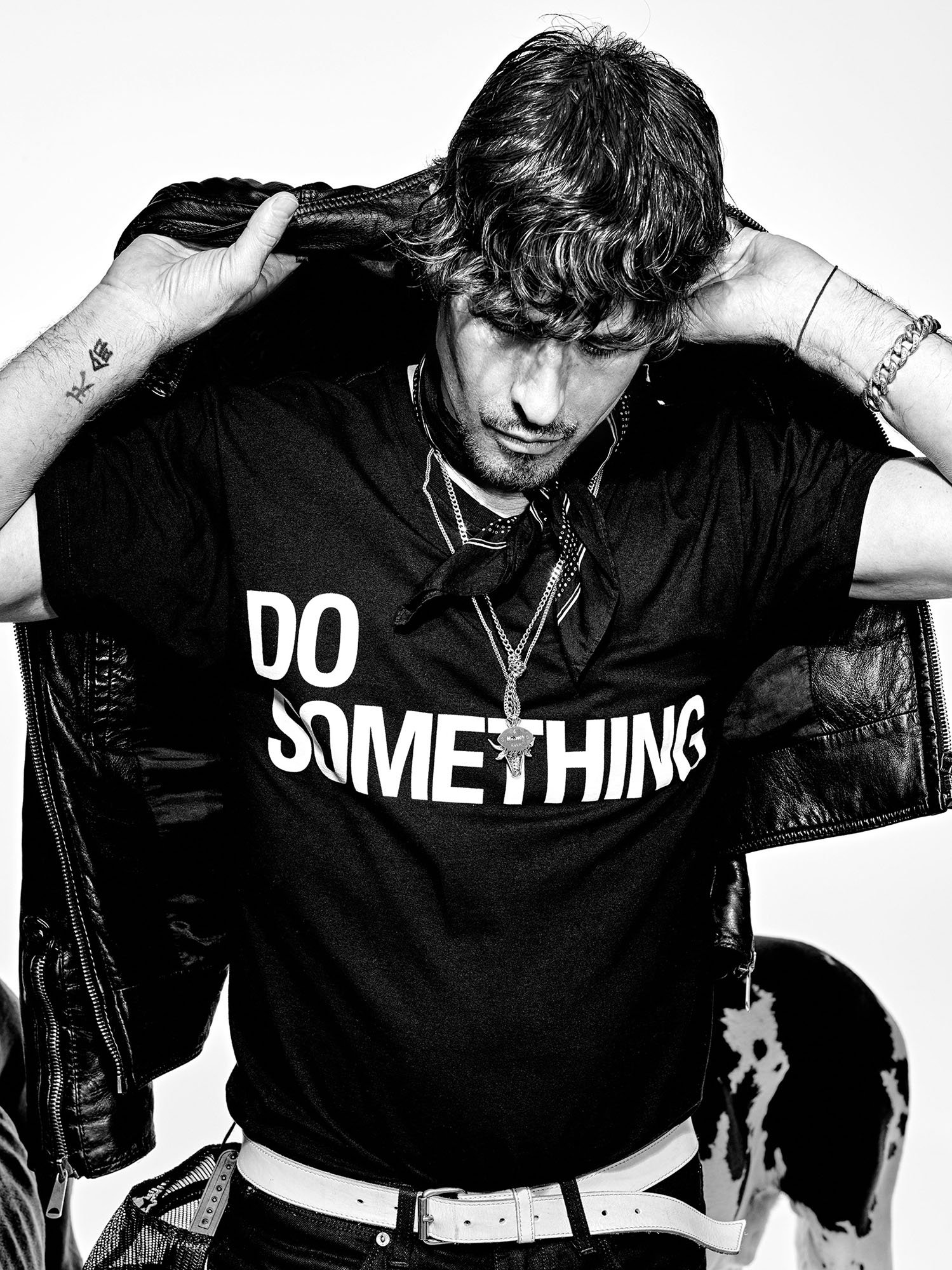

Steven Klein, Self-Portrait

Andrea: What about your self portrait which is blurred? How did that come about?

Steven: Oh, that I did for the New York Times, they did a piece on me several years ago. I convinced them to do a self portrait for that. For some reason, I wanted to do a self portrait and I think it's really hard to do a self portrait. At that time, I was doing a lot of pictures, a lot of self portraits on my computer on photobooth. Instead of using an iPhone at that time, I used to do a lot of self-portraits. I have thousands of self-portraits on my computer. So, I did several of them. The thing is it just happened to be in the winter time, and I remember the magical quality of the light. I don't know if you've ever had that experience with a picture, but it didn't look like that. Somehow it ended up from the snow and the reflections of the shadow. It came out unexpectedly. So, that's like a photo booth, photo portrait.

Andrea: I've heard through the years that you were quiet and shy. So when I saw that photograph, I thought that was your way of depicting that.

Steven: No. I mean, I'm always looking for interesting ways. I don't think I achieve it all the time, but the thing is I identify as a portrait or a depiction of a person, and I think it doesn't always have to be somebody staring at a camera. Seeing two eyes, a mouth, a nose and seeing the physicality as we know it. I think a portrait can be many different things.

Andrea: I love the image.

Steven: Yeah. I am shy at certain parts of my life. It's periods you go through. I think I can be very shy on set or working and other times not be. But to succeed in directing several people, you can't be too shy.

Steven Klein, Suburbia #23, Bedford, NY, 2007. Courtesy of Phaidon

Steven Klein, Hospital Drama, New York City, 2008; Courtesy of Phaidon

Andrea: How much do you direct people on set? Are you very different? I mean, how does cinema or your video work influence your photography?

Steven: Cinema's taught me how, when I was very hesitant to draw or or paint and I was just into just doing ceramics and didn't want to paint or draw, I was resistant to it. But, in the end, all those disciplines have helped me become better at what I do. For 20 years I've been working with different dp's, a lot of production designers, costume designers and many people in the film world. Eventually all of the still in the fashion world is moved into film. Luckily I got a head start on it. Also by studying film in school. I feel like film just helps me to be a better still photographer. It's thinking in a different dimension. Thinking in the film dimension, I call it, because it opens up your view and opens up the way. That technical aspect of the way that people work in the film world is a completely different way than the still world. For me, I feel more in line with cinema than I do in the still world.

Andrea: Because of the way they work, the results, your role, or all of the above?

Steven: I think all of the above. The structure of a film set, the trickery, what you can do in film, you know what I mean? The complexity of lighting and movement and storytelling. It's another level of visual thinking and storytelling.

Andrea: Would you ever consider doing a feature?

Steven: I'm actually working on a couple of projects at the moment. They're not completely defined as far as when and where yet, but that's been on the forefront for a while.

Andrea: Let me know.

Steven: For sure.

Steven Klein, Horse Pool, Guinevere Van Seenus, Windsor, CT, 2005; Courtesy of Phaidon

Andrea: You also take a lot of photographs of animals, which I adore. I'm wondering what inspired these pictures and would you say that you try to subvert the power dynamic between humans and their pets?

Steven: No, not at all. The only animals I’ve really shot are my horses and other horses that I've done studies with. I've done hundreds of thousands of them. I like doing the idea of a study and then I equate that back to all the nude figure drawings I've done in the past. And I used to do hundreds of those. I like the differences and nuances between doing one neck of one horse and another neck of another horse. I always shoot them in a certain time of year where the light's a certain way and against a similar wall. To me, it's a study of the muscular structure and the textures of the skin and the nuances of the anatomy of a horse. I don't really see them as pets, even though I have horses. As far as the study goes, I see them simply as studies.

Andrea: They're beautiful. I love horses. I really appreciate how you capture them. Another image I love is the picture of Madonna from the back in front of the horse with a crop in her hands.

Steven: Oh yeah, that one for Future Lovers.

Andrea: Beautiful image. Her back looks fantastic. Were you a sculptor as well?

Steven: I did sculpture as well, yes.

Andrea: Your interest in the human body can be seen throughout your photographs. The photographs can be taken on their own, due to their narratives, or part of a collection. What do you seek to expose and conceal in these images? They point to an exploration of the real or search for the authentic. You always create some sort of a mystery.

Steven: It depends what images you're speaking about, but generally speaking, I think that some of them aren't. What comes to mind is when you see a certain amount of evidence in a picture, say it's a police picture. One has to look at the evidence or look at a partial piece of a picture to understand what it's about. On a deeper level, what I'm trying to depict is the state of the world that we live in, the ambiguity that we live in, the state of chaos that we live in, or double standards. What my culture is, what kind of culture we live in today, what a pop star is today. Like the picture of Anna Nicole Smith is a portrait for her, but it was the idea of what she stood for then and how I photographed her. So, it's a little bit a sign of the times then and a sign of the times now, and looking back at certain things. For instance, I was at the Chateau when Helmut Newton crashed into the wall. The crashed side of his car is documented in one of the pictures. Some of them are true depictions of events. Other ones, I guess, could be fictional or could be glimpses of what's going on or what went on.

Steven Klein, Suburbia #23, Bedford, NY, 2007; Courtesy of Phaidon

Andrea: Steven, do you work with a team that helps you produce ideas? I know you collaborate with people, but the seeds, as you spoke of before, would you say they come from you or is it also a collaboration?

Steven: Well, I think that it's a collaboration, but the thing is that if I don't feel something, I don't do it. I have to always make it my own. If somebody says to me, “I'm working on something now” that they want to do or about an idea of the revival of a Renaissance image, I would never depict it in a literal way. I always try to think of my spin on things. Many of the assignments from Vogue would be the picture in the book of the two women or dolls that are by the pool without faces as a story on Botox. The picture with Tom Ford buffing the guy’s buttocks was based on a story about people changing their bodies, about implants and people changing their butts and changing their lips and doing that quite a long time ago. Tom had ideas about that. So I mean, I can't really say, but I do think it's a conversation. But, since I'm taking the picture, and at the end of the day, I think I always do take my picture, or it comes out being my picture no matter what.

Andrea: Well put. So what's next for you?

Steven: Finishing the book tour, but I don't know, probably planning a few books to come out in the next four to five years. And then also working on the feature film.

Andrea: I just want to ask you, going back to one thing, I'm just curious about-

Steven: The iPhone pictures?

Andrea: Well that and also the violence, working with depicting violence. What goes through your mind when you're doing that?

Steven: First of all, I don't think every picture's violent.

Andrea: I'm just talking about the ones so far.

Steven: The ones that are, I think, are a part of our culture. That's a part of our reality and that's a part of everything we see on TV. That's a part of having a child and dealing with a seven-year-old and seeing what's on. I'll give you an example, like in Charlie Brown’s Halloween, people are bullying, Charlie Brown's bullying other characters, and there's so much violence and guns and everything in our culture. Children grow up with it at an early age on the television, in movies, on the street, in our cities, our schools. Why wouldn't I include it in my pictures?

Andrea: I think you do a brilliant job. I’m just wondering how you relate to the violence? I know you're trying to depict what's happening in the culture.

Steven: The only thing I relate to is that it creates tension in a picture and creates some kind of dynamic structure in a picture when there's tension. That tension can be with color, and the tension can be with composition. The tension could be in the subject matter or the action of what's going on. But I think that when everything is too placid and quiet in the picture, I think that it can get a bit mundane and boring.

Andrea: We're going to be cut off soon, but I just wanted to ask you a quick thing about the iPhone pictures. Did you use the iPhone for a lot of the pictures in the book?

Steven Klein, Still Life with Apple and Helmet, New York, 1996; Courtesy of Phaidon

Steven: Well, you'll see which ones, and they're in the introduction. There's a bunch of still lifes I did. I did a series called YSL Death Kit. I did that over COVID with two fake dolls. The reason why that happened is because I couldn't get models. I took several pictures, probably 10 to 13, in the book that are called Death Kit. The thing is, I use my iPhone a lot, but more so during isolation because I didn't work with teams anymore. I really started to use my phone and I've been using it ever since. I’ve shot so many stories with my phone and iPad because I feel like the conventional tools of photography seem a little bit outdated since the phone came into play. The rendition of colors and lenses and ideas that I feel like the old cameras, and just cameras in general, depict scenes with lenses seem a little bit outdated in a way, or not really…Just the color rendition in the lenses, they don't seem as exciting as the iPhone or iPad lenses in color rendition sometimes.

Andrea: Great interview, Steven. Thank you so much.

No comments:

Post a Comment