Uncertainty overcame owners of several Manhattan parking garages in September. A plan to implement congestion pricing — charging drivers to enter a zone south of 60th Street — could lead to more transit usage by commuters, and thus the closure of some parking garages, The City reported. Parking options have already been on the wane in the largest US city: The NYC Department of Consumer Affairs and Worker Protection counted more than 2,200 licenses for garages and lots in 2015, a number that fell to 1,899 by 2021.

For most urban residents, if not outer-borough drivers, that decline is reason to cheer. The parking garage — a big, concrete-gray box for cars — is a notorious bane of urban vitality.

City after city, desperate to lure suburbanites downtown to work or shop, bulldozed prime real estate to build these structures in the postwar era, turning central business districts into vehicle-storage voids that sapped streets of pedestrian energy and hollowed out neighborhoods. Building codes that mandated a certain number of parking spaces have kept new garages coming: In suburbs, exurbs and towns across the US, you will find these facilities, squatting beside shopping centers and stadiums, airports and office parks, planned communities and amusement parks.

“Parking is the tail that wags the urban-development dog still,” says Tim Love, principal at the Boston-based design firm Utile.

The parking garage is such an inescapable element of modern urban life that it became essential pop culture infrastructure, site of many a cinematic brawl, car chase and dance number. It’s where Redford’s Bob Woodward met Deep Throat, where Sean Boswell had his ass handed to him before he knew how to drift. But the grim functionality of these spaces — not to mention their fundamentally somewhat anti-human function — has made them infrequent sources of design inspiration.

That’s starting to change, as architects and urban planners try to flip the script on these behemoths. The goal? Transform them from corrosive eyesores into structures that are both beautiful and inviting.

“There’s definitely been a push, especially in the last 20 years, to get these buildings architecturally attractive,” says Rachel Yoka from the International Parking and Mobility Institute (IPMI), an industry trade group in Virginia.

Building a House of Cars

In the beginning, cars just parked next to the horse.

Carriage houses served as the natural option for the opening decades of the 20th century, as existing infrastructure was quickly adapted to automotive application. It’s not until the 1920s that the urban prototype for a specialized building to stash motorcars appears, says Sarah Leavitt, who curated “House of Cars,” an exhibit on parking garages in 2009 at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC.

“They appear first in cities, places where there’s going to be way more cars than are going to reasonably fit,” Leavitt says. “And it also has to do with concomitant advances in urban development. The downfall of the traveling salesman means that people have to actually go somewhere to get what they want.”

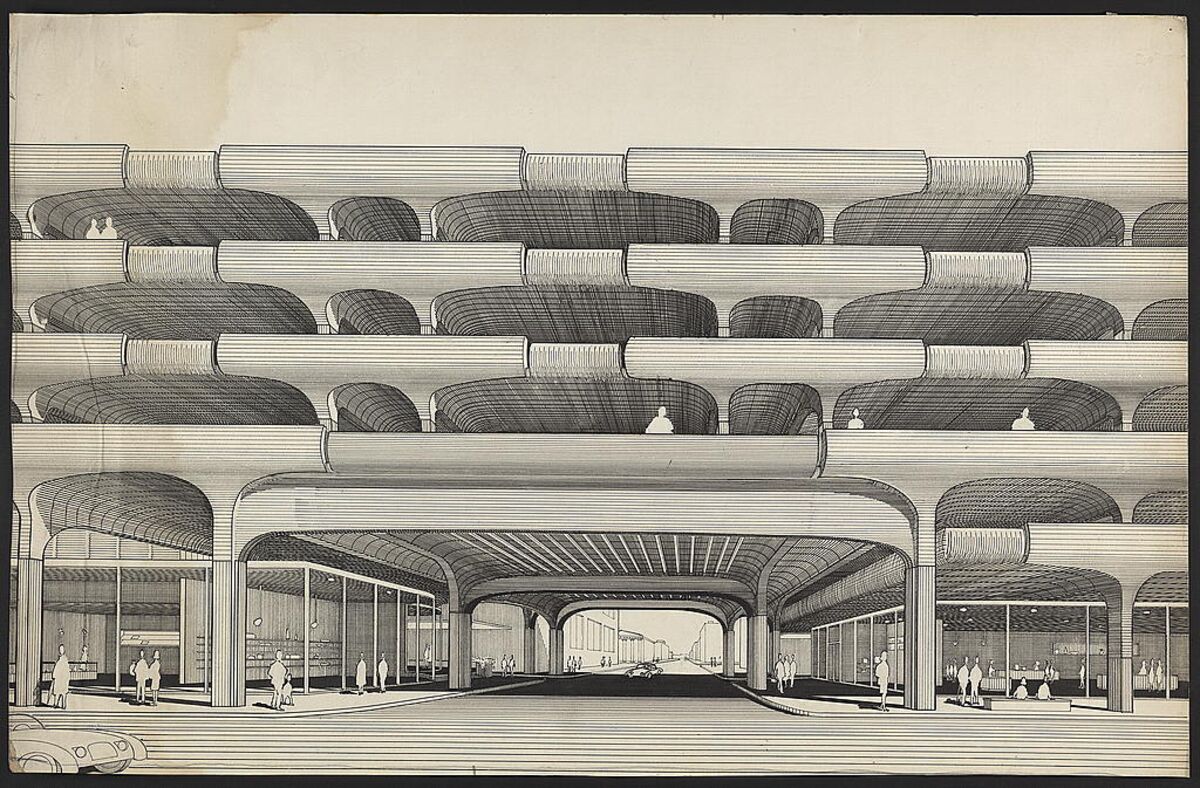

However, these weren’t the boxy structures most of us are used to seeing: Many early multifloor parking structures had pulley systems that lifted cars up to different floors. In Chicago’s Loop in the 1920s or ’30s you would find vertical affairs that stacked flivvers in freestanding towers via automated elevators.

Other garages could also look much like standard office or apartment buildings, with glass windows and rich ornamentation. In Manhattan, the Kent Automatic Garage company erected a pair of “hotels for autos” — Art Deco high-rises equipped with car elevators. The largest, a 24-story skyscraper on Columbus Avenue, held more than 1,000 vehicles. It’s since been converted to high-end residential use.

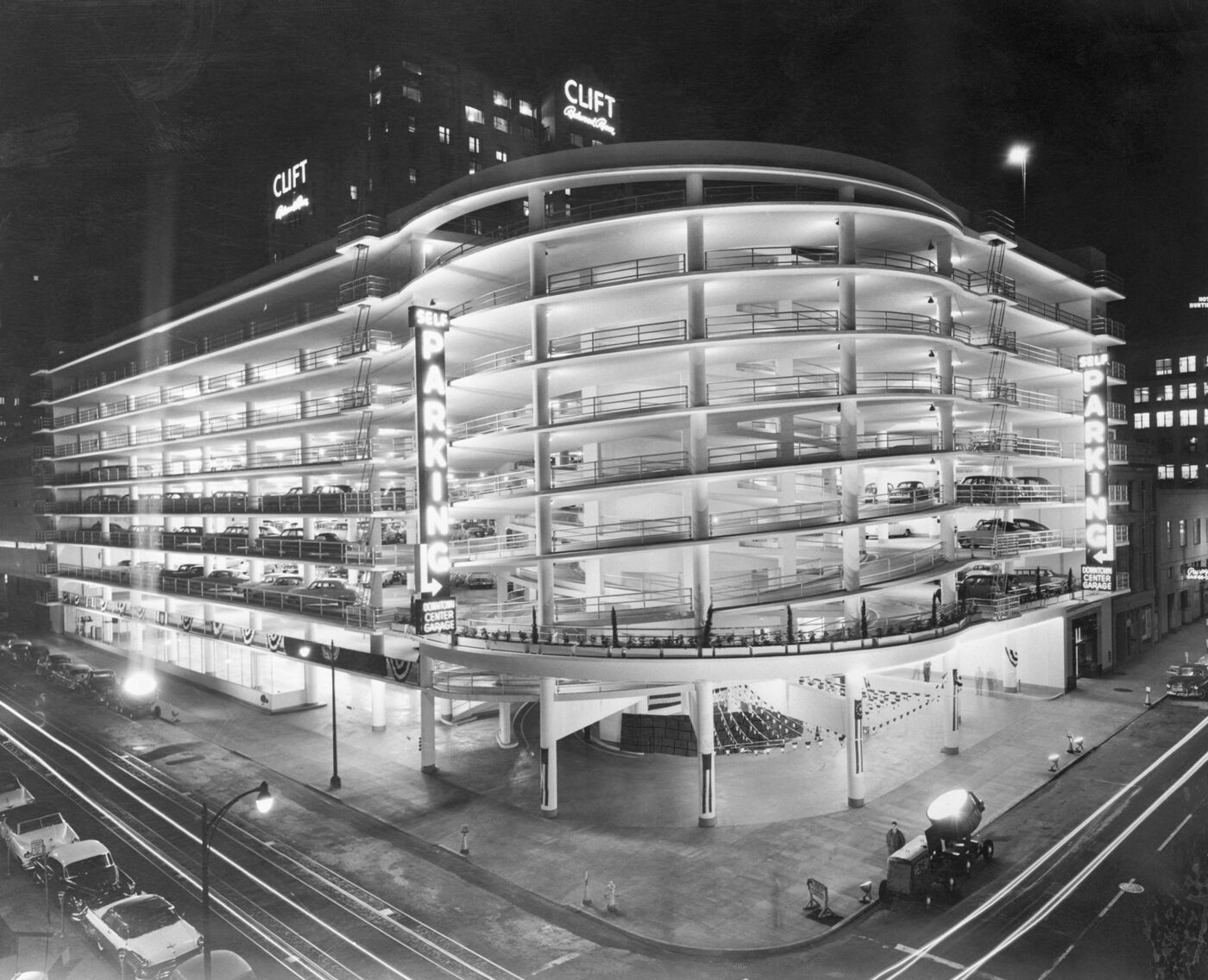

Self-parking structures with ramp systems that allowed patrons to drive their own cars up or down multiple floors arrived later, and with them came a more utilitarian approach, with open decks and less architectural decoration. The postwar era also saw an explosion of car ownership: In American cities, downtown developers raced to carve out parking for workers who expected to be able to drive to the office.

In Washington, DC, developer Morris Cafritz took that idea to its extreme, with a feature he called park-at-your-desk. The Cafitz Building, a Streamline Moderne structure on I Street, featured offices arrayed around a 500-car garage: Drivers parked, opened their car door, then opened a door adjacent to or very near their space, which led them right to their office door.

In Chicago, designer Bertrand Goldberg created an even more fluid hybrid of living, working and parking in Marina City, a mixed-use complex that opened in the early 1960s. Its office and residential towers were built atop 19 spiraling floors of car storage that blend almost seamlessly with the balconied apartments above.

But while architects penned the occasional signature parking structure — see Paul Rudolph’s 700-foot-long Temple Street Garage in New Haven, Connecticut, a two-block-long brutalist icon of the mid-1960s — most parking infrastructure made little effort to fit into the urban fabric or make a design statement, especially in the urban renewal years of the 1970s.

These are the parking garages that urbanists loathe: unadorned stacks of ramps and decks, assembled as cheaply as possible and built solely to absorb the flood of automobiles that city leaders and transportation planners, desperate to keep downtowns afloat, had invited into the city.

The Human Side of the Car Park

Today’s architects and designers, however, have new tools to make an eye-catching parking garage. Stainless steel meshes that allow for the application of graphics and artwork, as well as polycarbonate panels and new LED lighting systems, can help mitigate their ill effects, disguise their prime function, and even lure citygoers who aren’t behind the wheel.

“You don’t want it to be the standard gray concrete box,” says Dave Rich, a vice president at Rich & Associates Parking Consultants. “It’s all part of the movement of creating these walkable, user-friendly environments.”

One design trick — particularly popular in some Texas metros — is the so-called Dallas Donut, where, as in Morris Cafritz’s office building, the parking is tucked away behind more human-centered space, in this case layers of multifamily residential units. (The Utile staff call this model the “Texas Taco.”) From the street level, the building presents as a standard (if somewhat massive) mixed-use development; the hole of the donut is filled with cars.

Other solutions are more purely aesthetic. “There are solutions to cladding parking garages that can be just as sexy or attractive, to be honest, as an office building,” says urban planner Jeff Speck, author of Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time. He cites one well-known example: 2012 Cedar Springs Road in Dallas, an otherwise conventional parking garage clad in a wavy, metallic mesh that almost obscures the building’s true purpose.

Speck adds a crucial caveat, however. “What’s essential,” he says, “is that the ground floor be occupied with a human use.”

Perhaps the most well-known example of the garage-as-urban artwork approach is the Museum Garage in Miami’s design district, which holds 927 vehicles. The building itself, completed in 2015, boasts five colorful facades created by different designers. On the bottom floor of the garage is 22,000 square feet of retail space.

Garages can mix both parking and pleasure, and Miami is a standard-bearer on this front: IPMI’s Yoka calls the South Florida city “very progressive” when it comes to parking. At 1111 Lincoln Road, for example, parking isn’t even the main attraction. Designed by the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, the garage-cum-event-venue offers luxury retail and fast-casual food at street level; the top of the garage doubles as space for fashion shows, corporate gatherings and even weddings.

These spaces might not have been built with people in mind, but parking structures can serve as compelling stages for surveying the streets below.

“A parking garage creates a moment in a city where you have a roof where you can overlook the city,” Leavitt says. “You don’t get to just walk into any building downtown and see that view. But you can from a parking garage.”

Life After Autos

Those big, bleak parking garages that Rich speaks of had their heyday in the 1970s — a time when the economy was in the gutter and building a concrete box made more financial sense than trying to do anything pretty. Still, building a house for cars does not come cheap, and the costs associated with constructing new parking structures swelled further during the pandemic. According to the engineering firm WGI, the current median construction cost is $27,900 per parking space, or $10 million to $20 million for a typical garage.

Some architects, bullish on the idea that cities need to winnow down the amount of real estate devoted to parking cars, have proposed building future-proof garages that can be adapted to human use, or converting our generous stock of existing parking structures into offices or apartments. But that’s easier said than done, since the shelter needs of people and automobiles turn out to be quite different. Chases for plumbing and electrical conduits need to be built, the heights of standard parking garages are not readily suitable for conversion into office space or residential living, and their sloped floor plates and internal ramps present costly challenges.

There’s also a somewhat counterintuitive problem: People (and their stuff) weigh more than cars. The structural strength required to support vehicles is less than what’s needed to support an apartment, so reinforcement is required.

“Everybody’s talking about it and nobody’s doing it,” says Speck of garage conversions. “The real issue is getting cars out of cities.”

That process may be underway in at least some US cities, where tactics like congestion pricing and policy reforms like abolishing parking minimums aim to chip away at traffic and undermine the user base that has kept car parks full for the past century. It’s unlikely, though, that the parking garage’s days are numbered.

“For the foreseeable future, we’re going to need garages to park,” says Yoka. “They’re not going anywhere. But hopefully they’re getting prettier.”

No comments:

Post a Comment