| ||||

|

Here’s why Bhutan just gave itself a new ‘brand’

Bhutan’s new slogan and logo blurs the line between tourism campaign and national identity.

It’s 2022, and everything is a brand: companies, people, and even countries. After Peru, Estonia, and Japan, the latest example in the latter category comes from a tiny mountain kingdom in the Himalayas. But what does it even mean to brand a country, and does every country need a brand?

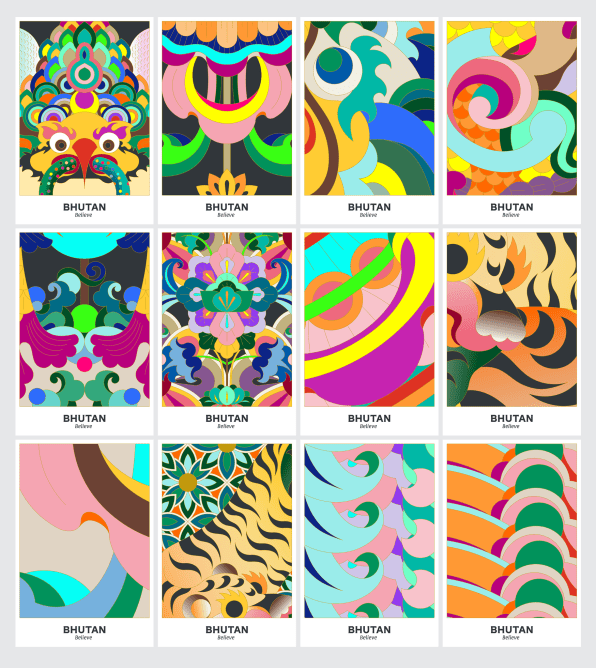

After more than two years behind closed doors, Bhutan has reopened its borders for tourists. To mark the occasion, the country unveiled a new national identity designed to inspire citizens and foreign visitors alike—and justify a new Sustainable Development Fee that’s gone up from $65 a day to $200. Designed by London agency MMBP & Associates, the brand centers around one word, “Believe,” and the visual identity reflects the country’s character and history through a kaleidoscope of traditional symbols rendered in bold and modern colors.

For the uninitiated, nation branding, or place branding, is all about using corporate branding techniques to promote countries. Tourism is the most obvious expression of that practice, but in this era of globalization, nation branding is also used to attract capital and talent, or to boost a country’s perceived prestige.

The practice dates back to the 1990s, when its inventor and former advertising executive Simon Anholt, defined it as the sum of people’s perceptions of a country across industries like tourism, immigration, culture, and people. In recent years, the practice has taken off to a point where nation brands now get ranked by a variety of institutions like the Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index (Germany topped the charts in 2021, suggesting that respondents felt positive about buying German products, investing in German businesses, or about the German government’s work to fight poverty).

Today, a growing number of countries, cities, and even neighborhoods have embarked on branding and rebrand exercises, from Japan to New Zealand to the Republic of Tatarstan. In some cases, a rebrand can be reduced to a simple logo or slogan; in others, it can become a full-on tourism strategy. But at its core, branding is an attempt to shift perceptions for one particular purpose or another (but more on that later). Some branding strategies, like Scotland’s “Best Small Country in the World,” last a few years then die out. Others, like Amsterdam’s “I amsterdam” have become so popular that the city had to temporarily remove the iconic “I amsterdam” sign after it caused mass tourism in the city’s Museum Square.

The Bhutan Believe brand is actually a rebrand. Aside from its rich biodiversity and lush nature, Bhutan is known for its “Gross National Happiness” index as well as its “high value, low volume” approach to tourism. For years, Bhutan promoted its tourism as part of a “destination brand” that would set the tone for potential tourists (it was called “Happiness is a Place.”) In 2018, the country adopted a new strategy called “Made in Bhutan,” which ended up being less of an identity and more of an attempt by the Bhutan Department of Trade to position Bhutan as an export country.

Bhutan’s attempts to rebrand itself highlight the challenges of the process. Like many countries, Bhutan is more than a tourist destination, despite its dependency on tourism for its economic health. The very nature of a branding exercise will inevitably flatten a country’s complexity to fit one particular context (most often this is tourism). That’s why MMBP & Associates spent the past four months dreaming up a cohesive identity that reflects the country more holistically.

Julien Beaupré Ste-Marie, the founder of MMBP, says the driving force for Bhutan’s rebrand was two-fold and targeted both local and international audiences. Tourism was Bhutan’s second highest source of revenue before the pandemic brought it to a standstill. Now that the country has reopened, the rebrand is meant to convey the country’s renewed commitment to sustainable travel and justify the higher Sustainable Development Fee that comes with it.

Before the pandemic every tourist traveling to Bhutan paid a daily fee of $200 to 250 for an all-inclusive package that had to be booked through a tour operator. Only $65 of that went to the country’s sustainable development fund, while the rest went towards food, accommodation, transport, etc. Now, tourists can enter the country independently, but they have to pay a daily fee of $200 per person as part of their visa application, exclusive of food, accommodation, and other extras. This means that visitors are now paying more for less, so part of the rebrand was about communicating why the fee that has essentially tripled. (Those reasons are laid out on a new website created by MMBP as part of the rebrand, where visitors are informed that the full $200 now goes to the sustainable development fund.)

Tourism aside, Beaupré SteMarie says the country has been experiencing a significant “brain drain” over the past few years as more young Bhutanese left in search of better opportunities abroad. (The trend appears to have peaked in 2018, but was still above average in 2021, when about 16,000 Bhutanese were living abroad, or 2% of the population.) In response, Bhutan has launched a series of education programs like the country’s first blockchain engineering program and a large scale upskilling program to train young people in fields like silversmithing, coding, or storytelling. As such, the new brand was designed to inspire young Bhutanese to move back, or never leave in the first place. “The brief for the brand was to be this self-fulfilling prophecy of engaging youth and renewed love and appreciation for the country,” says Beaupré Ste-Marie.

The rebrand is aspirational at best, naive at worst, but it brings up an important question about the validity of branding in a world where every aspect of our life is a play to make money. Over the past two decades, many war-torn countries like Croatia, Columbia, or even Rwanda have used branding to shift public perceptions. In the process, they’ve become booming tourist destinations. But does every country need a brand?

That depends on the motivations. “Almost every country in the world has a brand,” says Keith Dinnie, a professor of marketing at the University of Dundee School of Business in the U.K., who has written several books about place branding. “Unfortunately, you often get political leaders who see their neighboring countries have a branding campaign and they want one, but it’s not based on specific objectives.”

There are several triggers that often inspire countries to invest in a rebrand; it could be a failed campaign that didn’t resonate with locals (like Scotland’s “Best Small Country in the World” campaign, which Dinnie says ruffled a lot of feathers among locals and was later replaced with the comically bland “Welcome to Scotland”). Another reason might be a change in regime where “someone comes in and feels the need to do something new,” says Dinnie. Or, in the case of Bhutan, the government wants to rebuild the economies after the pandemic. But in the end, these reasons only make sense if they’re supported by clear objectives, like attracting tourists, foreign investment, or even international students for higher education.

Naturally, most rebrands come at a heavy cost (especially considering that money often comes from taxpayers pockets). Dinnie says it’s hard to prove whether any of them lead to more tourists, but the causal link between branding and investment is easier to track. He cites Great Britain’s so-called Great Campaign, which by some accounts has brought in over 4.5 billion pounds since it launched in 2011, by increasing exports and attracting foreign investment. Beaupré Ste-Marie declined to share the cost of the rebrand, and it’s too soon to say if the Believe campaign will have a tangible impact. I suppose for now, the only thing that people can do is “believe” that it will.

No comments:

Post a Comment