| The Kicker |

DECISIVE MOMENTS. The storied Italian photographer Ferdinando Scianna was profiled by the Guardian , and he uncorks so many great quotes that it is almost impossible to select a single line. But here is one. Discussing what he views as a crisis in photography that emerged in recent decades, Scianna said, “Today we all take photos with our phones, but they are background images. Even a selfie is not a self-portrait but a kind of neurosis about a moment of existence that must immediately supplant another, and so on.” In any case, these days he's “thinking about new books, exhibitions, working on my archive,” he said. [The Guardian] Thank you for being here. See you in 24 hours. |

‘I’ve taken a million pictures – 50 were good’: photographer Ferdinando Scianna

He’s photographed Scorsese, shot fashion for Dolce & Gabbana and created art from the religious rituals of his native Sicily. Now, at 79, Scianna declares his six-decade obsession with the camera is over

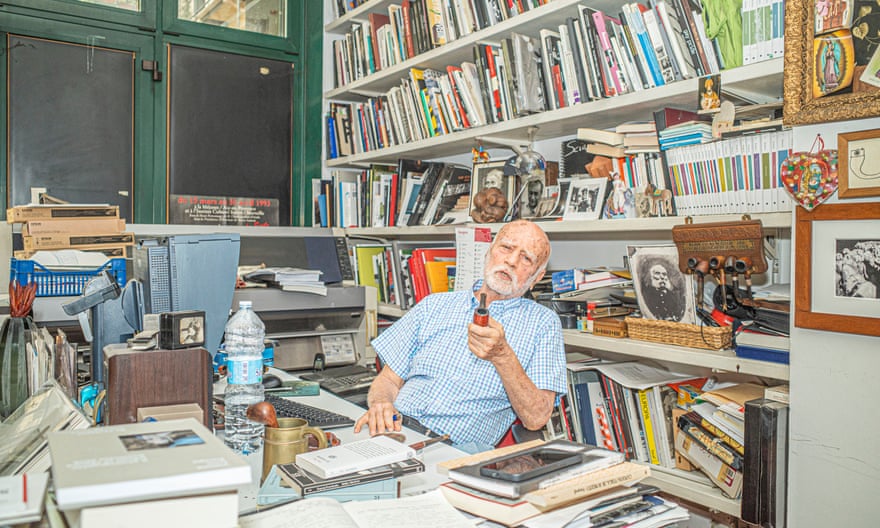

‘Do not call me master, for heaven’s sake,” says Ferdinando Scianna, welcoming me inside his studio, a cosy ground-floor space in the centre of Milan. “I do not teach anything to anyone. Come in, take a seat.”

Scianna has just turned 79. Photography, for him, was an obsession that lasted 60 years. “And it is over today,” he declares. He has not taken pictures for years and says that when young photographers approach him for advice, he wants to ask them for theirs instead. “I tell them the most obvious thing: photograph what you love and what you hate. But they should tell me how to sneak around in this weird era that I do not really know.”

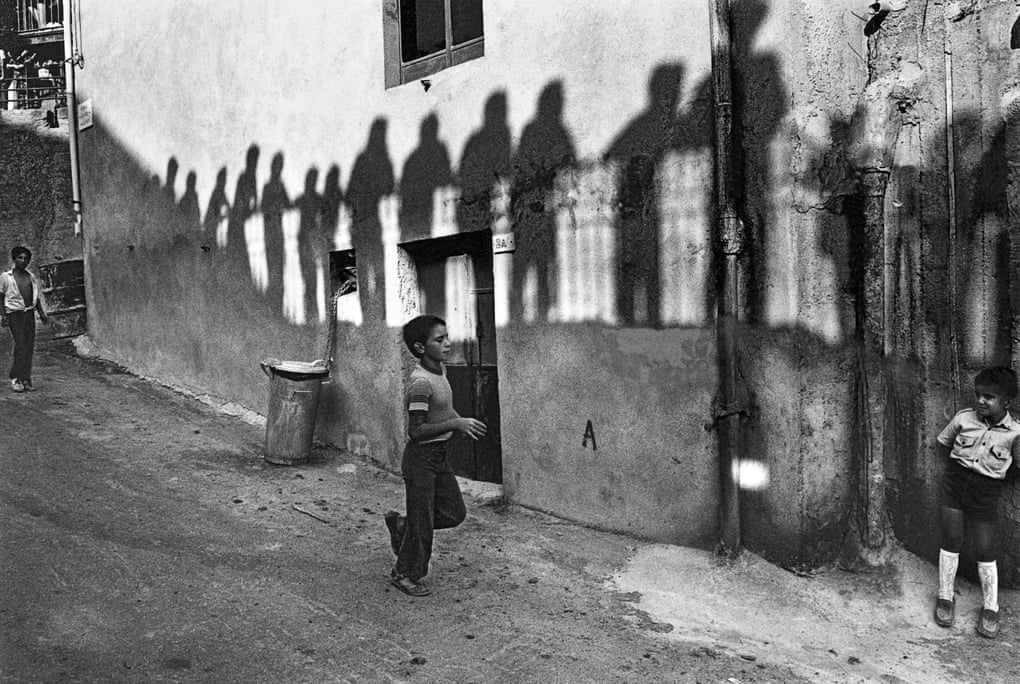

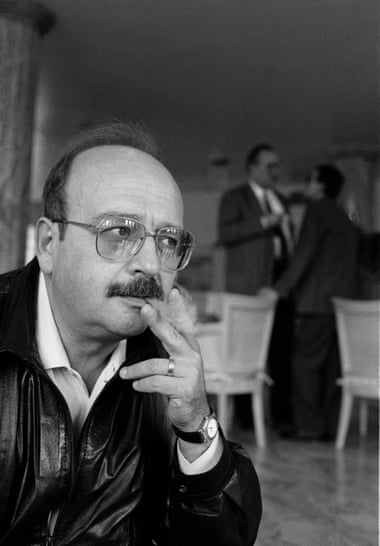

Scianna has taken more than a million photographs and, in his words, the good shots number about 50, including the series on the Roma photographed in the late 90s; the portraits of writers – Leonardo Sciascia, Jorge Luis Borges, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán; and one of his most famous photos, a boy running through Capizzi, a small Sicilian village, shadows imprinted on a wall behind him.

He loves to work on books though. He has published over 70; more, he says, than prudence would have advised him. The first was published in 1965 and is about religious rituals in Sicily (Feste Religiose in Sicilia). “I was just a 21-year-old Sicilian kid, and that book built my career. Today, when I leaf through the pages, I feel confused. I look at my photos and I ask myself, who took those images? I was too young and ignorant. You know, I learned to take pictures over the years – basically, just by taking them.”

Scianna was born in Bagheria, a village near Palermo. His first camera was a gift from his father when he was 16. “He wanted me to be a doctor or an engineer. Honestly, I do not think I have ever had the vocation of a photographer, I just wanted to leave Sicily and back in those days, I assumed photography was a passport,” he muses, lighting a pipe. His luck, he claims, is that he was part of a generation that had a zeal to change things, from women’s liberation to the 1968 student riots, while he was there to photograph it all. “In all of my generation, there was an unstoppable desire to fix the fragments of our world.”

Nonetheless, he says, he remained a Sicilian at heart. “Even if I left Sicily, I photographed Sicily wherever I went. A few years ago, I made a book about a mining village in the Andes, and someone said it is my most Sicilian book. At the end of the day, a photographer always takes the same photos. I do not know if that is a style or just a repetition. Well, maybe it’s just boredom.”

He unexpectedly achieved international fame in the mid-80s when the fashion designers Dolce & Gabbana chose him to shoot their campaigns. His photos drew on the subject matter he had always shot: social traditions, religious symbolisms, the matriarch as the leader of the family. “What an unexpected adventure, that one,” Scianna says. “I do not disown it, of course not. It allowed me the economic freedom to go and photograph just for myself.”

Scianna considers himself a diehard bressoniano – the Italian for fan of Henri-Cartier Bresson – and he was the first Italian to be admitted into Magnum, the prestigious photo agency. In his lengthy career he has taken pictures around the world but, unlike many photographers of his generation, never in war zones. I ask if he has ever been afraid of taking a picture. He smokes, thinks for a while, and says: “It’s like with dogs, basically. If you are afraid, people feel it and they become more aggressive; if they understand you are looking at them as human beings, they are OK. But no, I have never been afraid to take a picture. I was too afraid of losing my girlfriends,” he jokes.

Scianna doesn’t care for social media. He has an Instagram profile but it is managed by Nanà, one of his daughters. He knows that his black and white neorealist-style pictures collect thousands of likes and that most of them go viral, like the one he took of the Dutch model, Marpessa, for the Dolce & Gabbana campaign. In the picture she is posing while a little boy, who may symbolise Scianna’s alter ego, is photographing her.

“I do not think I can change the world with my photographs, but I do believe that a bad picture can make it worse,” he says. “And the point is that we have too many images. If you eat caviar every day, eventually you will want pasta e fagioli.” He thinks that photography went into an irreparable crisis a couple of decades ago, when we stopped building family photo albums. “Today we all take photos with our phones, but they are background images. Even a selfie is not a self-portrait but a kind of neurosis about a moment of existence that must immediately supplant another, and so on. And we all know what happens when something loses the identity that has determined its success and cultural function. It dies.”

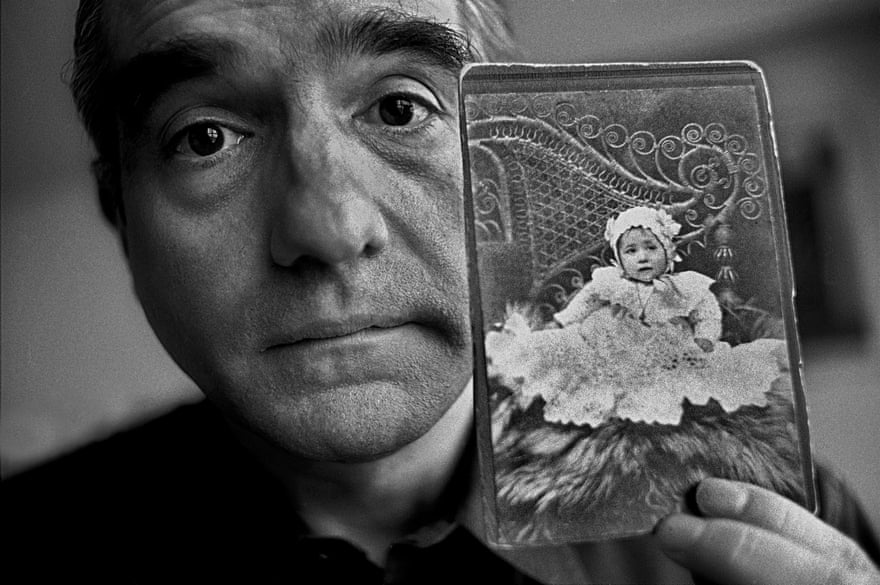

His office desk is full of novels, essays, books and a collection of pipes. Hanging on the wall are some photos of Martin Scorsese that he took some years ago for Vogue Paris. He decided to photograph the director holding a childhood portrait of his mother as a girl. “A photo can happen a few metres from your house or in the farthest away place in the world. You will never know in advance,” he says. After taking a long puff on his pipe, he declares: “Today everyone wants to write the fictional novel of what they would like reality to be: it is the era we are living in.”

He also disdains the pace of change driven by the internet. “On the web, everything is consumed quickly. Culture, on the other hand, is slowness and choice. I made my theory; it is the theory of the three risottos. Do you want to hear it?” He clears his throat. “If someone has never eaten a risotto in his life – and if they have never been to Sicily, they certainly never have eaten a good one – the first time they taste it, they can only say if they liked it or not. The second time, however, they can argue that it was better or worse than the first one. Only from the third time on can they have their own theory of risotto and, if they want, give advice on how it should be cooked. Culture, to me, is knowing things and having a choice.”

Scianna returns to the idea that photography is an obsession. “And, believe me, one day obsessions finish. When you are 79, you will find that the obsession with sex, for example, no longer exists.” He smiles, coughs a little and smokes again. Then he presses on his stomach and his face suddenly contracts in an expression of pain that lasts a few seconds. “Doctors say I still have a little more time to live. And for me, living means thinking about new books, exhibitions, working on my archive.”

His last solo exhibition was at the prestigious Palazzo Reale in Milan. More than 200 photos were on show and, on some days, there were long queues waiting to get in. “Graham Greene once wrote, while travelling from Marseille to Paris, at some point he deeply believed in the existence of God. With photographs it is a bit the same. And the world, you know, practises forgetfulness. Millions of men lived before us, men who had dreams, who have done things. We do not know anything about them.”

But then, I ask, what remains in history? “Things that have found their shape,” he replies instinctively, adding: “I have walked my entire my life only to take photos. I am like those little dogs who, while walking, have left their poop around the streets. But if you really want to know the truth, then yes, taking pictures has given me a lot of happiness.” He takes another puff on his pipe and watches the smoke slowly rise towards the ceiling until it becomes a giant white cloud that evaporates in a second.

No comments:

Post a Comment