14 Contemporary Artists on How Reading Influences Their Work

“Words are what culled my inner artist from the dead.”

If not for writing, I would not be an artist. Sounds dramatic, but writing is what ended my ten-year stint as a blocked shadow artist. After throwing myself into art as a teenager and getting a Fine Art degree from UCLA, I had big-time artist dreams as a young adult. Then something changed, and I stopped creating altogether. For most of my twenties, I worked as an art dealer, surrounded by art but never making it for myself—not until I started writing. I never had aspirations to be a writer. In college, I took one required Intro to English course, which I put off until my senior year. As an art dealer, I didn’t read a single book that wasn’t written by a Silicon Valley entrepreneur. I didn’t keep a journal.

And then, at age 30, I suddenly found myself writing. And more than just the to-do lists of before. I wrote pages and pages. About pain. About love. About fantasy. Once I started, I couldn’t stop. Obsessive writing soon led to obsessive reading. Which led to obsessive drawing, then painting, then—good lord—even an obsession with NFTs. Words, my words and those of others (Dodie Bellamy, Maggie Nelson, Roxane Gay), allowed me to pick up a pencil, a paintbrush, after so long without. They allowed my artist dreams to return, and for me to finally live them. Words are what culled my inner artist from the dead.

What exactly makes words so magical? So resurrectional? Especially for an artist like me. How was it that I could only break through my decade-long creative block via words, not images? It would be easy to reduce the power of words to that of the therapeutic. Of course, writing about oneself or reading about oneself via proxy can be cathartic. And, in my case, having less personal history with writing also made it especially fertile creative ground. However, I believe the magic that exists between art and writing goes beyond the therapeutic and into the physiological. That it, is the result of a toggling between the senses as they vacillate between sensory overload and deprivation. Art-making of any kind is as much in the body as in the brain.

It’s safe to say that most artwork is visual and that most writing is aural. Despite the fact that we use our eyes to read, we don’t so much see words as hear them. Words dance around in our cochlea, tapping their serifs to various tempos, whether or not they are technically articulated. Artists have an eye; writers, an ear. As an artist—or even an art dealer—it is easy to become visually overstimulated. Our eyes become numb as we stare at the same palette, same bodies of work, day after day, month after month, year after year. We look for ways to move forward. For visual solutions to our visual problems. But the harder we try to find the answers with our overburdened, desensitized eyes, the more infuriatingly elusive they become.

But then something happens. We put down our brushes, close our Photoshop files. Take a break from art fairs. We read a chapter, write a poem. Listen to an audiobook. And a different sense gets tickled. A sense that we’ve perhaps neglected. And then, all of a sudden, a kind of music fills our ears, and it’s like using a vibrator after years of self-chastity: the answers come and they come and they come.

–Mieke Marple

Reading: On Immunity: An Inoculation by Eula Biss

*

Jibade-Khalil Huffman

Reading: Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest by Hanif Abdurraqib

A large part of my work involves using text in the form of subtitles, titles, and more abstract juxtapositions of text and image in videos as well as lightboxes (and writing books of poems). Reading, both as research and for inspiration, then, of course, plays a huge part in the making of this text—where there is typically lots of veering back and forth between a clear sort of description/essay and the more indeterminate shifts of thought that poetry allows. Reading is as integral to my practice in this way as looking at images and watching films.

Jamie Chan

Reading: At The Center of All Beauty: Creative Life and Solitude by Fenton Johnson

During the lockdown in New York, I read At The Center of All Beauty: Creative Life and Solitude by Fenton Johnson. It’s about hermits (he calls them “solitaries”) and the ongoing creative tradition of relating to solitude. It profiles people like Zora Neale Hurston, Nina Simone, and Cezanne, but I got a lot out of the parts where he’s talking about his own childhood near Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky, where Thomas Merton lived. I enjoyed his descriptions of his father’s hermitage which was built from bourbon-soaked cypress barrels used in the nearby production of Trappist monks’ fruitcakes, and also had a tree growing through it; later, the land and house were sold. I thought a lot about how people learn from each other and the conditions for learning. I read it like a self-help book—it provided context, understanding, and encouragement to see the beauty embodied in the growing global population of people who choose to not marry or who live alone for various reasons. Living in the city, I rely on strangers for cues, kindness, and feedback in so many ways. This same question of presence and generosity is always there in art.

Magnus Maxine

Reading: On Freedom by Naggie Nelson

Reading often inspires great enthusiasm for my work in the presence of disparity, violence, injustice and the overwhelming sense that humanity and the planet are doomed. Reading has always impressed upon my mind the most vivid imagery that comes with an undeniable abundance of freedom, which is where freedom exists, in the mind.

Azikiwe Mohammed

Reading: Spawn Compendium Vol. 1 by Todd McFarlane Productions

As someone who writes with some frequency, I find reading a different discipline from making more visually oriented objects, and in my case not one that influences the other. When I read I visualize what I’m reading and read at the speed said action is taking place, which is the same way I make objects. Sometimes that can take a long time, while at others I find it swift. It is not my choice. It is an agreement made between reader and writer. This is in part why I take solace in Spawn. The speed is singular: slow. Nothing will happen for pages. It is drawn out in a way that feels luxurious, for me, as a Black man, rarely able to have time exist as such. The character Spawn is a Black man who has died, and in death found the time that I lack here while among the living. I look to hand back time to people in the objects I make. And also I love capes. And Houdini. And lists of three.

Hasani Sahlehe

Reading: How Music Works by David Byrne

In How Music Works, David Byrne details the creative, practical, and financial considerations artists make to do their work. I identify with Byrne’s many stories of unorthodox and innovative approaches to music-making. As a painter who thrives on bending material and genre, this book permits me to be me.

Oona Brangam-Snell

Reading: After Claude by Iris Owens

I like the melodramatic tone and symbolism used in Victorian novels specifically—like the man who gets drunk at a bar and auctions off his wife and newborn baby in The Mayor of Casterbridge. Because those writers couldn’t reference things like sex so explicitly, they had to hint at them through these lush descriptions of nature or gothic architecture. A lot of modern novels read like screenplays and they just aren’t as visually potent. I love those books because they leave the most brutal elements of a story to my imagination—and that creates a fertile environment for visual ideas.

Chris Dorland

Reading: Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson

My creative development would not have been possible without books. Both my parents are academics and I grew up in a house literally popping at the seams with books. It’s impossible to exaggerate the sheer volume of books. My dad first introduced me to cyberpunk as a kid—I’ll never forget him quoting the now infamous opening sentence. He was really annoyed that he couldn’t find Neuromancer for me at the bookstore and had to settle for Count Zero, which he thought was a lesser book. I kind of disagree!

Unfortunately at the moment I would say my stupid phone is ruining my brain. I find it increasingly challenging to find time to focus and read, which is totally a bummer and something I try to fight as much as I can. That said, I love a good literary thriller, my favorite subgenre being thrillers that involve an artist or painter as the protagonist. I recently discovered Emily St. John Mandel’s work (most known for Station Eleven, which I haven’t read yet but gleefully devoured the HBO series). Her thrillers are great. She has a wonderfully straightforward prose that I really appreciate. I randomly stumbled on The Glass Hotel last year and am currently reading The Lola Quartet. Station Eleven is next on my list.

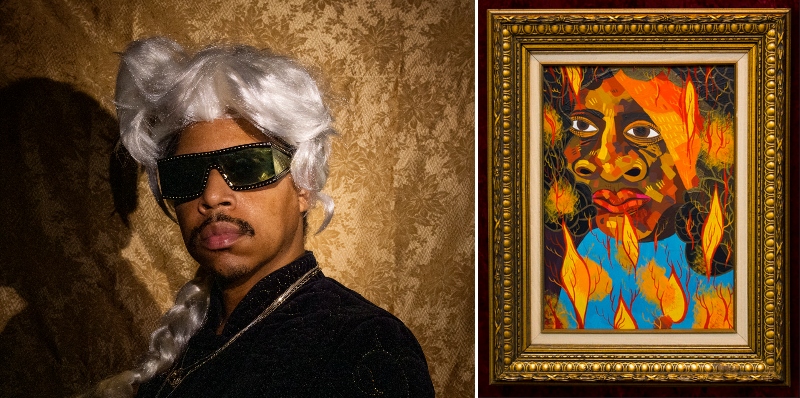

Kalup Linzy

Reading: Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta by James Hannaham and What Happened to You?: Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing by Bruce D. Perry and Oprah Winfrey

While in college, I spent a lot of time reading self-help and New Age books. These books were chosen from Oprah’s Book Club. They include Joseph Campbell’s Power of a Myth, Neal Donald Walsh’s Conversations With God, and Iyanla Vanzant’s One Day My Soul Just Opened Up. All of these books influenced my artistic practice. Campbell’s theory that most movies and religious stories follow a 12-plot point journey of a hero informed how I shape my narratives. I titled my Conversations Wit De Churen series after Walsh’s book series. And Vanzant’s books informed how I dealt with my own and my characters’ conflicts.

Recently, I read an advance copy of my friend James Hannaham’s book Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta and What Happened to You? by Bruce D. Perry and Oprah Winfrey. The former is fiction about a transgender woman paroled from a men’s prison, and the latter is a self-help book with the retelling of real stories about trauma matched with scientific analysis. Hannaham asked if I would create artwork for the cover and I did. The cover represents the character, her environment, and the mood I felt while reading it. Perry and Winfrey’s book is me checking in on myself. It is actually influencing my current short series that I am writing, the working title Not Ready To Say Goodbye.

Frances Waite

Reading: Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry by Randolph M. Nesse

Reading is a huge part of my art practice. All of my drawings are anchored in narrative, many of them existing (for me) in a shared world, populated with familiar interiors, characters, crises, and so on. Reading a good story inspires me to expand and further explore the corners of the universe that I’m building in my work.

Right now I’m reading Good Reasons for Bad Feelings. This is really about the “human experience,” which is something everyone talks about (including me) that I’ve always felt clueless and confused about. My recent work has a lot to do with dread and doom, so I’ve found it really cool to read about “bad feelings” from a scientific and objective perspective. Evolutionary psychology is also interesting in its own right, and I’m really enjoying learning about it.

Adam De Boer

Reading: Killing Commendatore by Haruki Murakami

While I didn’t know it at the beginning of the novel, Killing Commendatore is actually a drawn-out commentary about how any artist struggles with integrity. The book is about art’s historical legacy, and how contemporary viewers and painters must digest and learn from our cultural forebears in order to move on, both as producers of culture ourselves and human beings in general. The climax has the main character, a portrait painter whose name you never learn, enter a traditional and foreboding landscape painting by a celebrated Japanese painter named Tomohiko Amada in order to rescue his young neighbor and model. It’s a complicated narrative to say the least, and this “entering” of a landscape may be just a metaphorical dream sequence, but as is common with Murakami, nothing is certain.

Regardless, the book gave me my first opportunity to see how even stylized conventions in art history can be rich in drama and narrative. Oftentimes as a painter, repetitive themes and formal conventions become cliché to the point they are almost invisible to the super-informed viewer. But to most casual viewers of the object (which are most of them), the magic can still work. In a very oblique way, the book helped me see why conventions in art history in both the East and West—portraiture, landscape, still life, et cetera—endure for a reason. There is something universal in those genres that cannot be made obsolete. Our job as artists working today is to comment on how those conventions work in our lives. Hopefully, if we do a good job, there will be something of use for future generations to learn from and react against.

Julie Mauskop

Reading: The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images

I think about the meaning behind certain symbols when I sketch out ideas for paintings; I want to convey a certain mood based on what symbols can evoke. Yet I’m also interested in letting my unconscious mind be at play while sketching, so the interpreting of what I do sometimes occurs after I create a painting. In my work I repeat certain subjects such as floating limbs and pillows and dynamics that might occur in a bedroom or dream space. There are also figures which resemble frogs, snakes, or various other animals.

The Book of Symbols talks about frogs, saying that, “Because of the much longer back legs than the front, the adult frog is often perceived as bearing an endearing resemblance to a miniature human being, or something between the human and the uncanny.” This symbolism goes along with the idea that I wish to present a hybrid of human, animal, and alien forms.

Another part resonated with me about why I paint figures with no hair: “While baldness is associated symbolically with receptivity to the spiritual and with new life, it also evokes psychic as well as physical nakedness and acute vulnerability…images of beginning and end, masculine and feminine, nature and spirit lose their sharp distinctions.”

In talking about bedrooms, the book describes how it can be a “timeless place” and a “haven of stillness” yet at the same time be connected to the idea of exposure or anxiety. It also says how the history of this word is associated with protection and enclosure. These ideas relate to the environments I wish to create in my paintings. I like how a painting can contain multiple archetypes, combining phenomena that we’ve experienced to produce something that can be seen both collectively and subjectively.

Sophie Treppendahl

Reading: Funny Weather by Olivia Laing

My wonderful friend, Molly, sent me a copy of Funny Weather by Olivia Laing. The book is made up of short essays about art and artists and the challenges they faced in their lives. It arrived at a moment when I was feeling out of sorts in my practice, and it felt so nourishing to step out of my own head and spend some time in other artists’ stories. Some artists in the book I knew well, like David Hockney and Georgia O’Keefe. The artists that have stayed with me from this book are those who created in spite of overwhelmingly challenging circumstances: Derek Jarman and David Wojnarowicz, and, with a very different challenge, Sargy Mann. While Funny Weather was just an introduction, I’ve since started reading a few books by the artists Laing profiles (Close to the Knives by Wojnarowicz, Modern Nature by Jarman). My work, during the pandemic, has been zooming in on my own personal domestic spaces, painting my home and the objects it’s filled with. The last two years have me (and all of us) feeling isolated, and I don’t think I realized how insular my practice was becoming until recently. This book was a healthy departure from my own head into someone else’s practice and a humbling reminder of the necessity of art, for all of us, in the face of challenging times.

Nick McPhail

Reading: In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

I just re-read In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki for the third time. The way he urges us to think differently about the design choices in our world that we take for granted is profound and poetic. It’s also a plea for preservation. Tanizaki talks in length about the endless beauty and appeal in what is visually left out, covered, or omitted. He specifically refers to traditional Japanese theatre costume and architecture, but I think it can be applied to anything. In my work, I am constantly suggesting rather than directly showing. I think about how much information can be removed from a painting, and how that can allow the viewer to fill in the blanks with their own memories and experiences. Tanizaki also argues for a traditional style architecture that reveals its beauty slowly over time and causes its occupants to be more appreciative, mindful, and aware of their surrounding structures. I aspire for that level of presence and gradual expansion in my work, and Tanizaki helps remind me of how important this slow discovery is to the human experience.

_______________________

Platform is the e-commerce destination for buying art from today’s most sought-after artists.

No comments:

Post a Comment