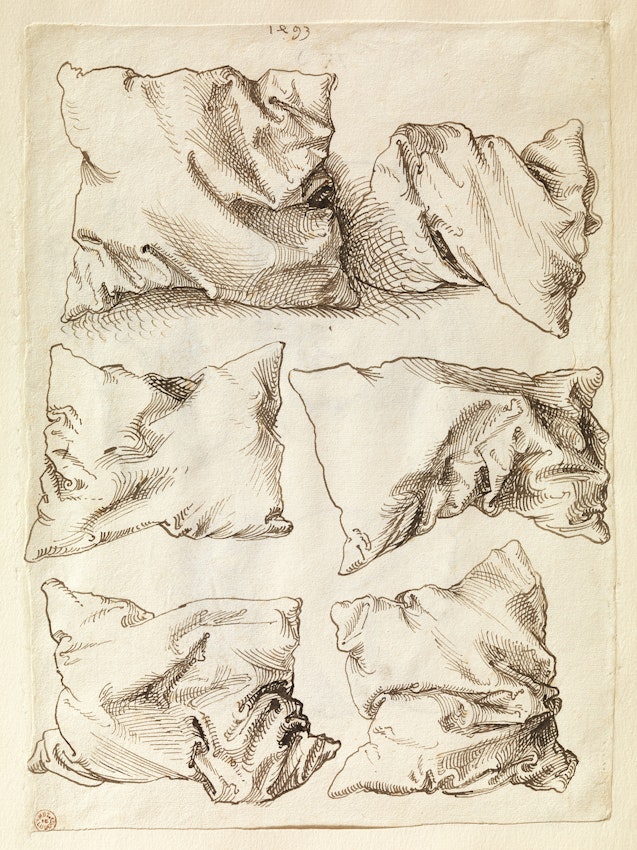

Albrecht Dürer’s Pillow Studies (1493)

Completed in his early twenties, Dürer's pillow studies can seem to slip between the waking world and the stuff of dreams.

In his early twenties, after years of wanderjahr-ing across Europe, Albrecht Dürer returned home to Nuremberg, now fully trained in his craft. During this moment of transition, the young artist completed a double-sided line-drawing in pen. On one side, we find a self-portrait of Dürer. The artist is bodiless, except for an outsized hand, posed as if holding a pen too thin to see. A pillow appears below his shoulder-length hair, pressed into a hatched shadow, which mirrors the darkness of his palm. While the artist’s portrait is believed to have been a preparation for Portrait of the Artist Holding a Thistle (1493) — considered “one of the earliest independent self-portraits in Western painting” — the presence of hand and cushion create an unlikely trinity. There is “a harmony that you wouldn’t expect at first”, says curator Stijn Alsteens, as the observing eye, recording hand, and object of study come into alignment. Yet there is also something uncanny about the chosen perspective, for the pillow “looms upward toward the viewer, unsupported, at an angle that is difficult to explain”. This spatial ambiguity, argues Freyda Spira, “brings to life a composition that could easily have looked like three isolated studies”.

On the verso side, we find a composition brought to life in another way — six pillows, contorted into the shape of fitful sleep, which seem to slip between the waking world and the stuff of dreams. There is the same spatial ambiguity of the recto: the hatching on the first two pillows extends beyond their borders to become shadows on the page, while the other cushions float in a depthless vacuum. No countenance of the artist features here, but if you look long enough, the cushions’ folds may assume the contours of distorted faces. “Once set in motion”, writes Joseph Leo Koerner, “this game of ‘seeing as’ can be played indefinitely, transforming corners into noses, chins, or satyrs’ horns, and creases into mouths and brows, until each pillow is animated by a number of hypothetical masks frowning, laughing, fretting, and speaking”. The drawings take the German word for pillow, Kopfkissen (headpillow), literally, fashioning Kissen into Kopf.

Dürer’s treatment of the pillow can be neatly nested in the tradition of “drapery studies”, a vehicle for a young artist to explore the play of light on folds and its expressive possibilities. And yet, when viewed in relation to Dürer's self-portrait overleaf, the six pillows also read like notes toward the artist’s later aesthetic theories, articulated in the postscript to the third volume of The Four Books on Human Proportion, especially his concern with dream, reality, and the imagination’s recombinatory powers. “Therefore, if he [the artist] were to live many hundreds of years, and labor to the best of his abilities, if he so wished, through the power of God he would daily spill out and make new forms of men and other creatures that nobody had ever seen or thought of before.” Anticipating Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s description of the imagination’s esemplastic power — “a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation. . . [the imagination] dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to re-create” — by several centuries, Dürer also admonishes the would-be Prometheus. An artist “should be cautious not to make something impossible that nature would not allow, unless it would be that one wanted to make a dream work [traumwerk], in which case one may mix together every kind of creature.” These pillows, then, might be viewed as a kind of memory foam, which not only preserves the partial imprints of a sleeper’s face, but also the fantastic, hybrid creatures that populate her dreamscapes.

No comments:

Post a Comment