Art

Paula Rego’s Darkly Ambiguous Paintings Reflect on Abuses of Power

Portrait of Paula Rego with Stray Dogs, 1965. © Manuela Morais. Photo by Manuela Morais. Courtesy of the artist and Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

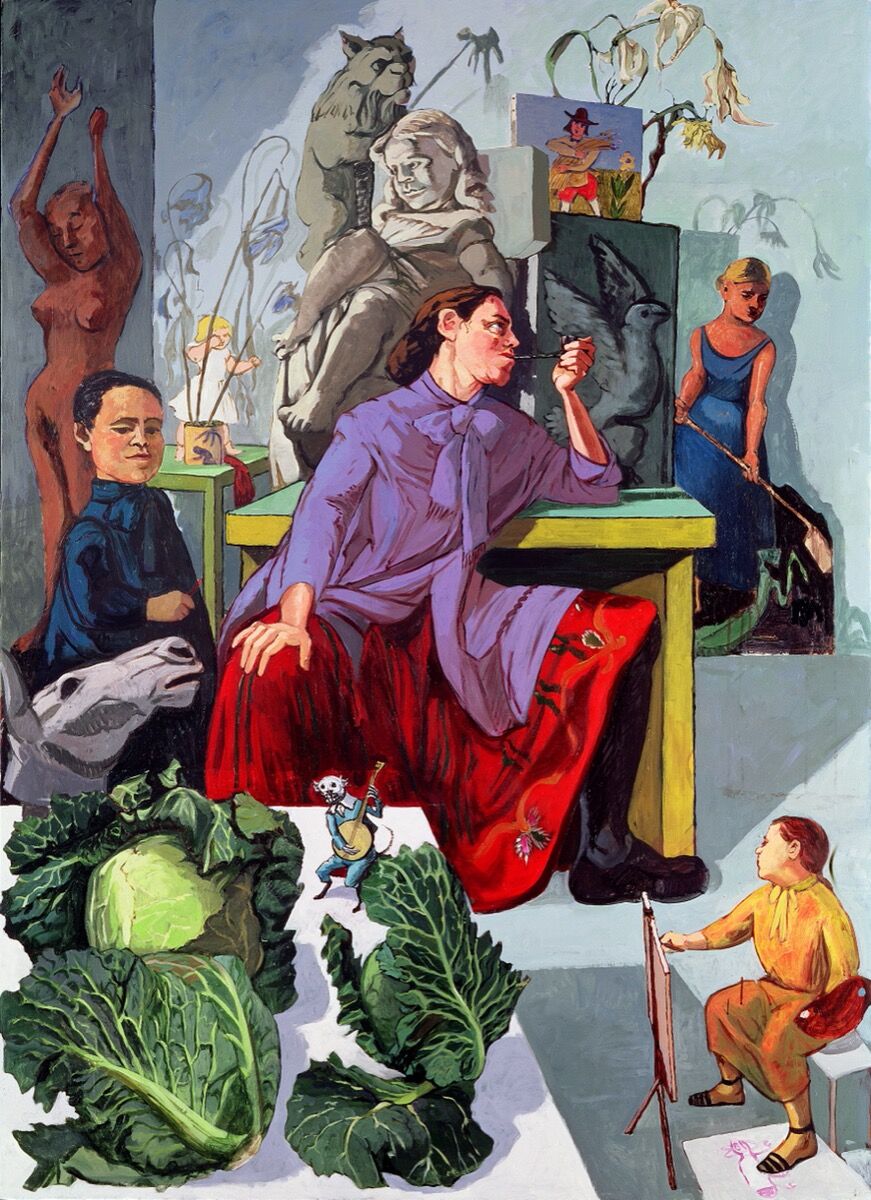

In The Artist in Her Studio (1993), paints herself in profile, pipe in mouth, legs spread wide, right hand placed firmly on her knee. Playing with the archetypal image of a male artist in his studio, Rego asserts her right to sit alongside them in the canon.

Rego, who turns 87 in late January, is today recognized as one of the leading artists of her generation, celebrated for her darkly ambiguous worksthat draw on a dizzying array of sources ranging from folklore and fairy tales to literature, theater, and personal experience. A major retrospective of Rego’s work, which gained rave reviews at Tate Britain and is now showing at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, reveals both the extraordinary range and ambition of her paintings, as well as her formidably courageous spirit. Rego’s work from the last 20 years can also be seen at Victoria Miro in London in her solo exhibition “The Forgotten,” on view until February 12th.

Confronting abuses of power, while also exploring the complex desires and emotions that lurk beneath the surface of us all, has been the primary focus of Rego’s vast and eclectic oeuvre. Growing up under the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal, the artist was attuned to injustice, particularly against women, from an early age. Interrogation (1950), painted when Rego was only 15, shows a woman, head bowed in despair, sitting in front of her interrogators. One figure menacingly holds a drill while the other has a conspicuous bulge in his trousers. An allusion to the sexual torture so often inflicted on women, the work shows an awareness of the psychological impact of such abuse—a recognition almost disturbing for someone so young.

Sent to boarding school in England to escape Salazar’s oppressive regime, Rego would later attend the Slade School of Art in London, where she’d meet her future husband, the artist . During the 1960s and ’70s, Rego experimented with influences ranging from and to and in works which were unapologetically anti-regime and anti-clerical. In Salazar vomiting the homeland (1960), which features an abstracted male figure spewing yellow bile, Rego hurls her disdain for Salazar’s administration at the canvas. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it proved so controversial that it was not publicly exhibited until 1972, two years after the dictator’s death.

A turning point in Rego’s life came after a series of personal tragedies. Her father died in 1966, and soon after, Willing was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. In addition, her father’s company, now under Willing’s control, was facing collapse. These combined events caused Rego to plunge into depression and eventually seek the help of a Jungian psychoanalyst. Rego’s therapist encouraged her to explore in depth the fairy tales, myths, and biblical stories she had been surrounded with as a child, and which, according to Jungian thought, were a source of archetypal human behavioral patterns. Rego’s research into the origins of these tales—as well as favored illustrators as diverse as , , and —provided reference material that she would return to throughout her career.

Her vibrant gouaches of the mid-1970s have an enigmatic fairy tale–like quality, but by the 1980s, her work had transformed into -esque anthropomorphic canvases that play out frictions in Rego’s marriage. Therapy helped Rego realize that in Wife Cuts off Monkey’s Tale (1981), she was depicting her attempts to become independent from Willing, both as an artist and wife.

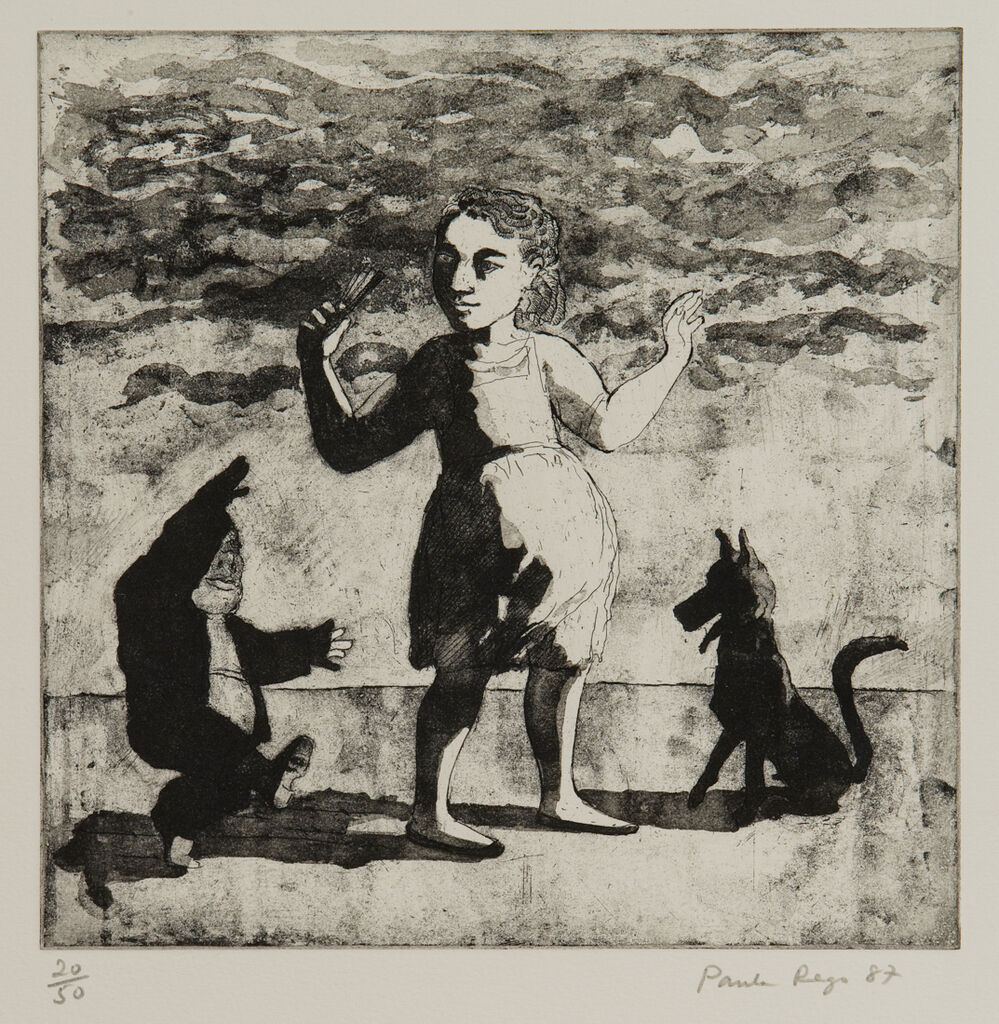

By the mid-1980s, Willing was entering the final stages of his illness. Tate curator Elena Crippa notes in the exhibition catalogue that this coincides with a major shift in Rego’s work, which takes on greater psychological depth and begins to use the body to express emotion. In the unsettling series “Girl and Dog” (1986), in which a young girl is seen toying with a dog in her care, Rego explores the complex emotions she experienced as her husband’s caretaker.

It is also at this time that her figures take on their familiar robust, sculptural quality. Surrounded by enigmatic symbolism and imagery, the characters in The Little Murderess (1987) and The Cadet and his Sister (1988) play out unsettling stories with conclusions that remain deliberately obscure.

Paula Rego, The Dance, 1988. Courtesy of the Tate and Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Willing died in 1988, leaving her a letter in which he wrote, “I know you will paint even better. Trust yourself and you will be your own best friend.” Shortly after, Rego painted The Dance (1988), a nocturnal dreamlike composition in which her late husband appears twice: once, dancing with a woman who may be Rego, and again, with a woman who certainly isn’t (both Rego and Willing had affairs). To the left, a woman dances alone. Is this Rego embracing her new freedom? As in all her work, nothing is clear.

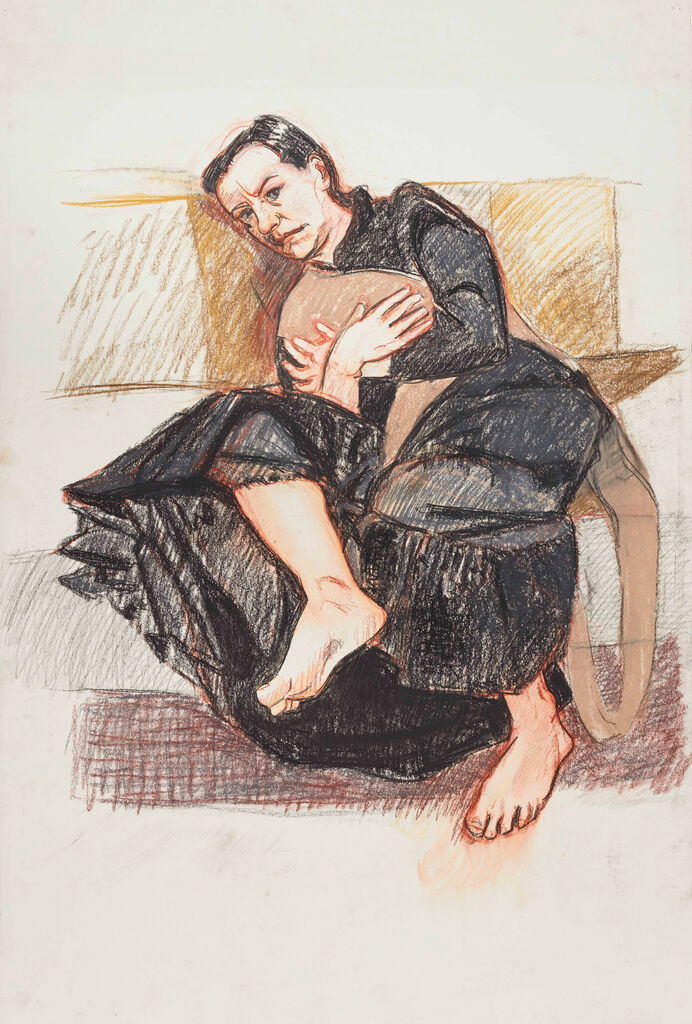

Certainly, she mourned his death. The 1994 series “Dog Women,” featuring women crouched and howling in animalistic poses, is seen as a raw expression of the grief Rego felt at the time. However, Laura Stamps, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, points out that the series—created in the pastels that would increasingly come to dominate Rego’s work—have also been read as an attack on patriarchal depictions of the female form, particularly in ’s pastel scenes. “He was a voyeur of the female body, and in this series, we are voyeurs of female emotion,” Stamps told Artsy. “She is confronting art history, forcing us to not only look at the exterior of women, but also at what they are experiencing.”

Female experience has been at the heart of Rego’s work in recent decades, most notably in her series of pastels created after the 1998 referendum that failed to legalize abortion in Portugal. The viscerally powerful series pointedly features women and girls from all walks of life curled in agony from the procedure or crouched over basins and towels, waiting for it to take effect. Such was their impact that the series is credited with helping a second referendum pass in 2007.

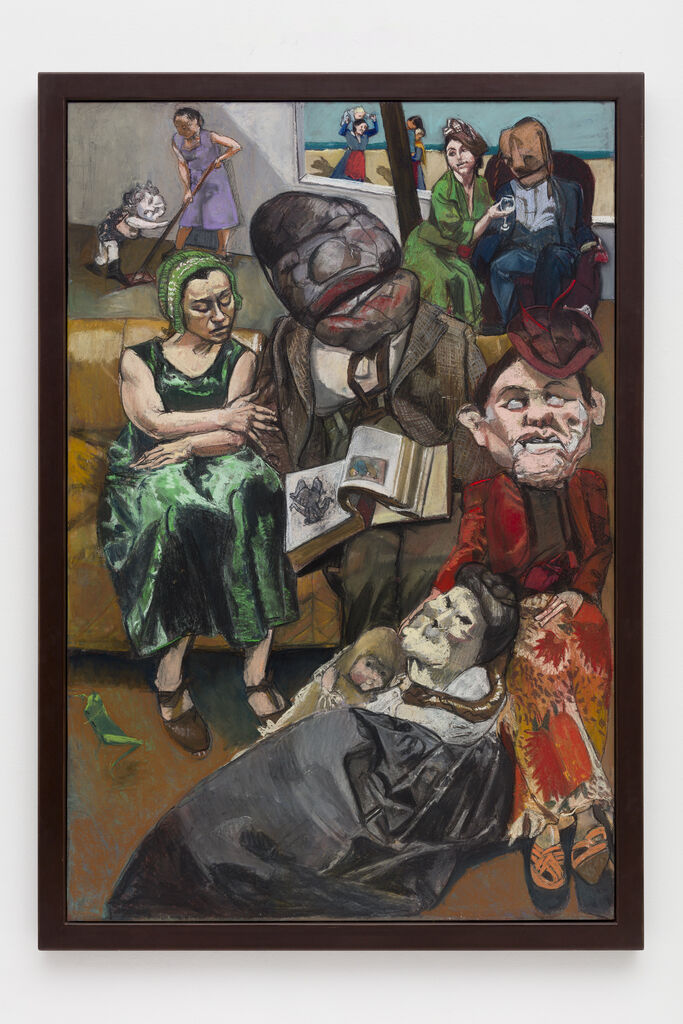

More recently, Rego has addressed human trafficking and female genital mutilation. Featuring masked characters and the soft sculptural figures that Rego has created since the 1970s, these provocatively theatrical compositions recall the works of and , drawing her audience in with a false sense of security before they are forced to realize the full horror of what they are witnessing.

Paula Rego, The Pillowman, 2004. Courtesy of the artist and Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Horror of a very different sort is on display in The Pillowman (2004), inspired by the play of the same name by British playwright Martin McDonagh. Rego recognized a kindred spirit in McDonagh, whose macabre tale shows the title character transporting people back to their childhood and persuading them to commit suicide in order to avoid an unhappy future. She takes the character as a springboard to explore her own life in three pastels, which Stamps believes to be among Rego’s finest work. “There are so many elements that make her works interesting, and in a way, they all come together in this,” Stamps said. “It’s about literature and play writing, theatrical settings, her personal life, the stories the church gives us, it’s all there.”

No comments:

Post a Comment