Op-Ed

Why Do Forgeries Sometimes Deceive Even the Most Venerable Experts? Because We All Want to Believe

As the author of the catalogues raisonnés for Grandma Moses and Egon Schiele, Jane Kallir has encountered a lot of fakes in her career.

As the author of the Egon Schiele and Grandma Moses catalogues raisonnés, I see an average of one fake a week. Most are so inept that they would not fool even a moderately experienced dealer or auction-house employee.

But while successful, large-scale art forgery scandals are relatively rare, they tend to garner disproportionate attention. Plans are underway to turn the recent documentary about the Knoedler Gallery scandal Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art into a feature film (the director wants Meryl Streep to star as disgraced art dealer Ann Freedman). Wolfgang Beltracchi, the German forger reputed to have faked some 300 paintings by 100 artists over a 40-year period, starred in his own documentary, The Art of Forgery, directed by his attorney’s son, Arne Birkenstock. While Freedman, director of the once venerable (and now defunct) Knoedler Gallery, was excoriated for selling over 40 fake Abstract Expressionist canvases, Beltracchi was lionized in the German press as a sort of Robin Hood figure. Either way, the stories become morality tales about art-world greed and corruption. But the reality behind such cons is far more complex.

Why were so many experts fooled? The answer lies as much with the conned as with the con artist.

I was 25 years old when I encountered my first Schiele forger. It was exciting: I got to work with the FBI and wear a wire. After a botched sting operation, the FBI raided the alleged forger’s home and came away with a trove of evidence, including the typewriter that had been used to falsify a letter of authentication. Nonetheless, the suspect was never charged.

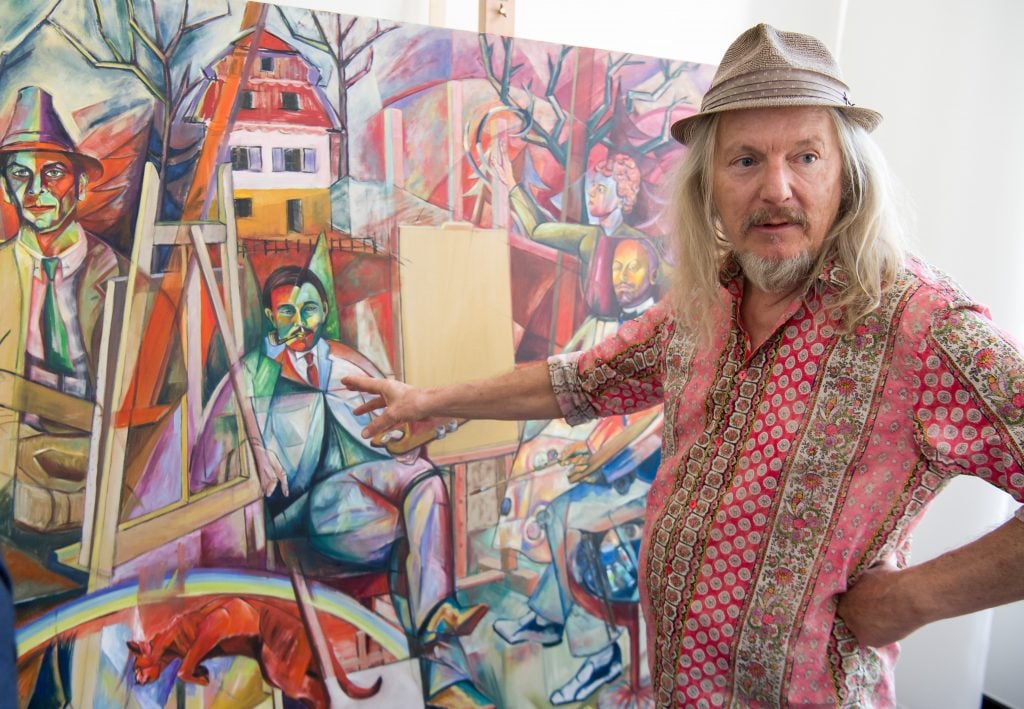

The painter Wolfgang Beltracchi stands in front of his painting. Photo by Peter Kneffel/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Generally speaking, it is not illegal to sell a forgery unless one knows it is a forgery, something that is exceedingly difficult to establish in a court of law. Freedman was not criminally indicted, and though she faced 11 civil suits for fraud, each was settled without a conclusive verdict. Only she knows what she knew. The German police had plenty of evidence that the Beltracchi paintings were forgeries, but they could not easily prove that he painted them. In the end, he struck a plea deal, confessing to having forged a mere 14 works in exchange for a reduced sentence.

Whereas there are presumably still hundreds of undetected Beltracchi forgeries out in the world, the reach of the Knoedler debacle was more circumscribed. In addition to Freedman, it seems only one other dealer, Julian Weissman, bought the fakes, which were painted by a Chinese artist, Pei-Shen Qian, and peddled by an obscure Long Island dealer, Glafira Rosales. Once Rosales confessed, the entire scheme fell apart. As with the Beltracchi con, confession was key. Without it, the lawsuits against Knoedler would have degenerated into contests of opinion, because Freedman, like Beltracchi, initially had a number of experts on her side.

Image still from Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art (2020).

David Anfam, Dore Ashton, Stephen Polcari and E. A. Carmean, Jr., were among the scholars who commented favorably on various Qian fakes. A supposed Barnett Newman and a Mark Rothko were exhibited at the Beyeler Foundation, and the “Rothko” had been accepted by the National Gallery of Art for inclusion in a forthcoming catalogue raisonné. Similarly, Beltracchi’s forgeries were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and sold by Lempertz, Sotheby’s, and Christie’s. His fakes fooled numerous scholars, among them the esteemed Max Ernst expert Werner Spies.

How did this happen?

Both the Beltracchi and the Rosales scams rested on elaborate invented backstories. Beltracchi said the works came from the collection of his wife’s grandfather, Werner Jägers. The forger not only created the paintings, but he also staged a pseudo-historical photograph of the collection in situ and crafted fake labels for the noted prewar dealer Alfred Flechtheim. It was those labels—strikingly different from the genuine article—that eventually tripped Beltracchi up. Qian’s forgeries were likewise given a fictitious provenance, but Rosales, unlike Beltracchi, failed to provide any documentation. While this made it impossible to confirm the provenance, it also made outright refutation more difficult. When her original story failed to check out, Rosales simply added another name to the chain of ownership. Each change in the provenance sent Freedman’s researchers chasing down a new rabbit hole.

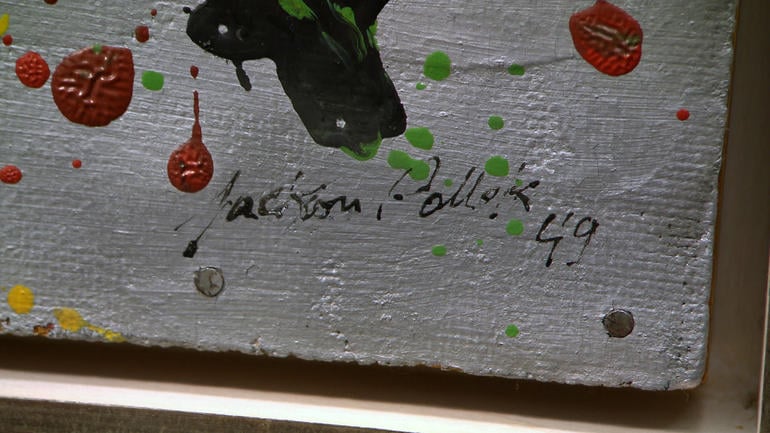

The signature from a Knoedler painting that was purported to be by Jackson Pollock, but is misspelled “Pollok.” Courtesy of James Martin.

Maria Konnikova, whose book The Confidence Game includes a chapter on the Knoedler case, has observed that, “If you are the victim of a con that you truly believe in, as evidence comes in against you, you are much more likely to double down.” Of course, greed is a factor, but ego is at least as important. Dealers and collectors alike relish the prospect of making a great “find,” and when challenged, some want to believe they are smarter than the experts. In my experience, people love their fakes. Indeed, fakes can be more beautiful than authentic works, because forgeries lack the elements of uncertainty, searching, and discovery that distinguish the true creative process. Daniel Filipacchi, owner of a Beltracchi “Ernst,” told Vanity Fair it “was one of the best Max Ernsts that I have seen.”

Several months ago, I was contacted by the owner of a mid-sized regional auction house. He told me he had just driven several thousand miles cross-country in a snowstorm (at the height of the pandemic) to retrieve a collection of studies by “degenerate” artists, some with the collector’s stamp of Hitler’s henchman Hermann Göring. I knew even before seeing the collection that the works had to be fakes. Sketches this small (all were housed in eight-and-a-half-by-11-inch binder sleeves) are usually not so obviously ascribable to famous artists. The Göring stamps, a misguided attempt to establish provenance, would, if genuine, have raised troubling questions about Nazi loot. (Forgers don’t always think these things through.) When I met the auctioneer, he regaled me with tales of the spectacular discoveries he’d made over the course of a lengthy career. He was partly in thrall to the romance of the present story (the drive through the snow, the mini-masterpieces), but his in-house researchers had already prepared him to accept the truth. The drawings were clumsy copies of well-known works by Schiele, Klimt, Kokoschka, Dix, Beckmann, and others.

Konnikova believes that everyone is potentially vulnerable to victimization by a skillful con artist. In the face of our universal gullibility, we seek foolproof, scientific ways to determine artistic authenticity. However, as James Martin, the conservation scientist who helped unmask the Beltracchi and Qian fakes, notes, forensic analysis alone is not always sufficient. It is only effective if the forger made a scientifically detectable error, for example by using materials inappropriate to the work’s purported date of execution.

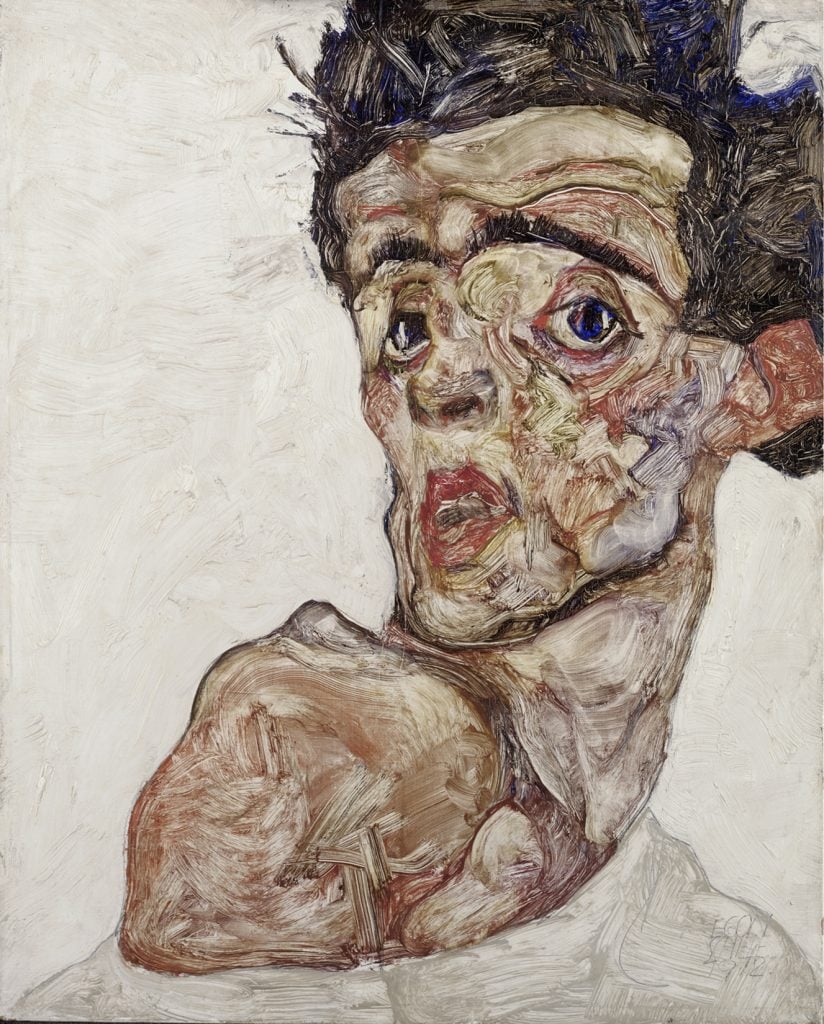

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Bare Shoulder (1912). Courtesy of the Leopold Museum, Vienna.

A lot of the Schiele fakes I see are accompanied by extensive reports attesting to the fact that the pigments used existed during the artist’s lifetime—which in no way establishes authorship. And forensic analysis tends to be less helpful with works on paper than with oils, because oils have more complex substrates that can be subjected to testing. The practicality of scientific testing is further limited by the fact that it is time-consuming and expensive. That said, Qian’s Rothko forgeries could have been detected with the naked eye, because they were painted over a white primer—something Rothko never used during the period in question. The problem is that almost no one was paying attention, because they were already hooked by the story.

Wolfgang Beltracchi with a forged painting supposedly by Max Ernst. Photo by Brill/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

All experts make mistakes. Andrea Firmenich included five or six Beltracchi forgeries in her Heinrich Campendonk catalogue raisonné. Jack Flam, president of the foundation that oversees the Robert Motherwell catalogue raisonné, initially accepted one of Qian’s Motherwell forgeries. Nonetheless, when confronted by additional fakes, both Firmenich and Flam grew suspicious. They began making inquiries and commissioned forensic tests that turned up historically inappropriate materials. Firmenich’s and Flam’s ability to acknowledge their mistakes ultimately led to the downfall of Beltracchi and Rosales.

A member of the vetting committee at work at TEFAF Maastricht 2019. Photo by Loraine Bodewes courtesy of TEFAF Maastricht.

If one defines a “forgery” as a work created with the intent to deceive, most faux Grandma Moses paintings are not really forgeries, but rather copies of famous works made by admiring fans. I was thus caught off guard when a seemingly genuine, undocumented Grandma Moses composition turned up for sale at a New York auction house in 2015. The provenance was unusual: the painting belonged to a Hungarian woman who had supposedly acquired it in Canada, and the identifying label that customarily appears on authentic Moses paintings had been cut out of the backing. These red flags, however, led me to suspect theft, not forgery. After an Art Loss Register search came up clean, I gave the auction house my OK. Then, a couple of years later, the Hungarian consignor submitted another Moses painting, and around the same time a second auction house brought in one that had been purchased in Hungary by an American collector. The forger had made more obvious errors in these two paintings, and with some digging, we found prototypes for all three fakes online. To muddy the trail, the forger had transposed the seasons (i.e., changed summer to winter and vice versa) when copying the original Moses landscapes. I immediately informed the auction houses and the FBI, though I imagine the Hungarian culprit was beyond the reach of American law enforcement.

Authentication is not an exact science, much as we may wish it were. James Martin likens it to a three-legged stool, resting equally on provenance, forensic testing, and connoisseurship. I would add that one must also be willing to question one’s assumptions and be ever on the alert for new scams.

Jane Kallir is president of the Kallir Research Institute.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

It looks like you're using an ad blocker, which may make our news articles disappear from your browser.

artnet News relies on advertising revenue, so please disable your ad blocker or whitelist our site.

To do so, simply click the Ad Block icon, usually located on the upper-right corner of your browser. Follow the prompts from there.

SHARE

No comments:

Post a Comment