Sin City

New York nightlife never stopped. It just moved underground.

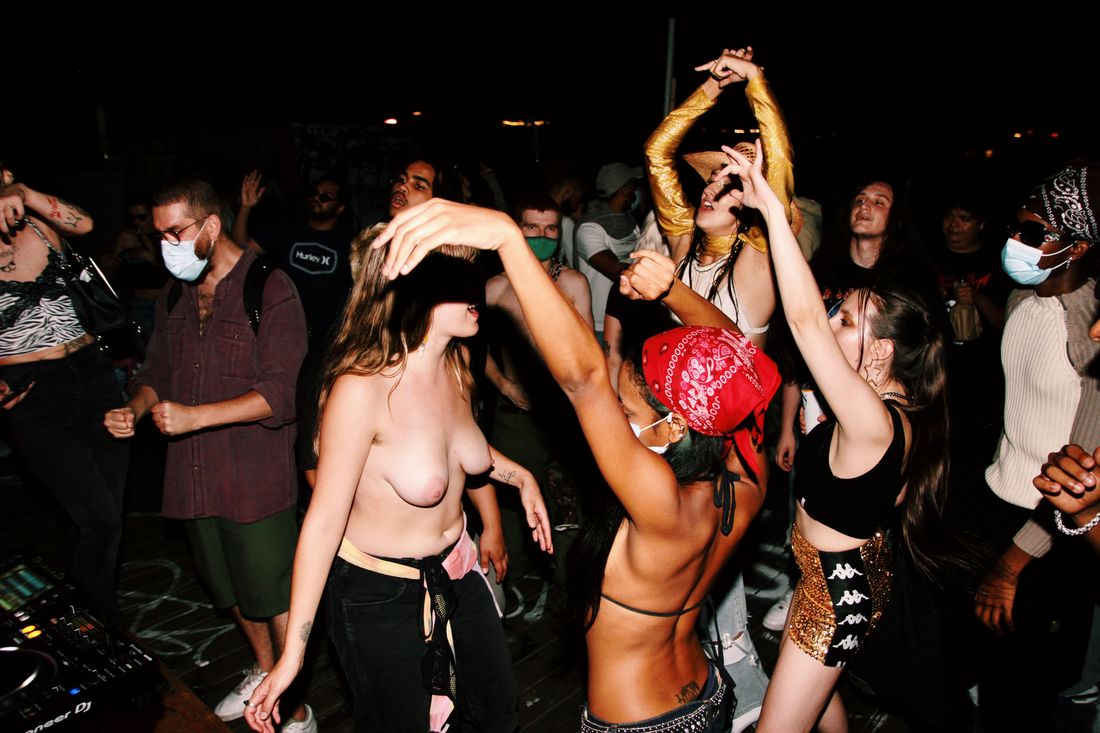

It’s 2 a.m., or, per the guy sitting next to me, “the hour where nothing is awkward,” on a Friday night less than two weeks before the presidential election and three weeks before COVID-19 positivity rates would creep back toward 3 percent in New York, prompting a series of new lockdown measures — a night and moment that, in retrospect, would be the twilight of New York’s pandemic reprieve. On the teeny back patio of a vacant industrial warehouse on the border of Bushwick and Williamsburg, at a covert party named, fittingly, “Dirty Dark Underground,” I can find only one person out of a couple dozen revelers who appears to even own a mask, though his is currently dangling under his chin. If you happened to wander into this party, lured from the street by the muffled sound of electronic dance music bumping off the walls of the 2,000-square-foot space, you might have thought it was 2019 again, when the bottom halves of our faces were left unadorned by swaths of fabric and sharing something you smoke, something you drink, or someone you sleep with didn’t put your life in danger.

“What are you smoking? Want to switch?” says a woman in leopard-print tights, grabbing my cigarette and offering her e-something in return, which I politely decline. “What is this?” she asks incredulously, though it’s just a Marlboro. A few puffs later, she offers it back to me. “Oh no! Please! Do keep it,” I tell her, and she seems to take it as a sign of generosity, rather than a desire to avoid exchanging saliva with a complete stranger in the middle of a global pandemic.

Partying in New York never really stopped. Even in April, as the virus swept through the city at a ferocious pace, stories circulated about secret events organized through Instagram DMs and held in private lofts, shuttered clubs, and emptied warehouses. On April 20, the NYPD busted a party of 38 people celebrating the holiday with a smoke at 4:20 p.m. on West 23rd Street. By that time, the virus was infecting 3,000 city residents a day, and the death toll had exceeded 10,000. Through executive order, Governor Cuomo had shut down all nonessential businesses and gatherings regardless of size.

By late July, when positivity rates lingered around 1.5 percent and the orders were eased to allow gatherings of up to 50 people, the underground party scene was as rich and varied as the aboveground one used to be. There were boat parties, pool parties, karaoke parties, sex parties, silent-disco parties, park parties, house parties, warehouse parties, and roof parties. There were Meatpacking table-service affairs that required shelling out a few grand for a couple of seats and hotel parties in Long Island City that mandated a dubious COVID test for entry.

The urge to party isn’t class-specific. For every good bottle of Champagne consumed on a Manhattan rooftop, there was a handle of Taaka vodka being passed around a circle somewhere. This illicit summer saw a Bushwick brownstone that threw enough parties to be declared the “Illmore,” along with crowded outdoor park events that took place in the light of day. In their most flagrant pandemic-defying jubilance, party organizers have staged warehouse ragers, spreading the word via Instagram about indoor and outdoor all-night events with rotating DJs and unlicensed bars. In July and August, a small park under the Kosciuszko Bridge became infamous for its giant parties, one of which was billed as a Black Lives Matter fund-raiser, according to Gothamist.

One weekend in October, I found myself at a different warehouse in Bushwick, near a gay bar that allowed indoor dancing if you didn’t leave after last call. In a crowded backyard, people danced as the organizers sold pre-rolled joints (“No one licked it. It’s corona. We get it, we get it”), hosted a twerking contest, and raffled off edibles. An Afroed emcee declared to the crowd, “I just want to remind everyone this is a 420 space,” and, soon after, “We all exist on a spectrum.”

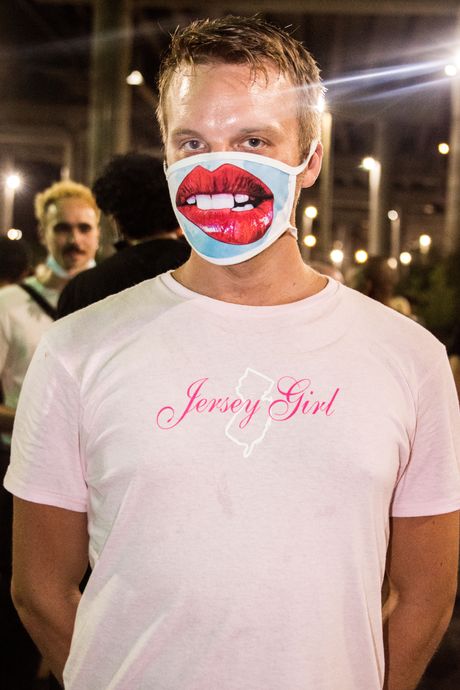

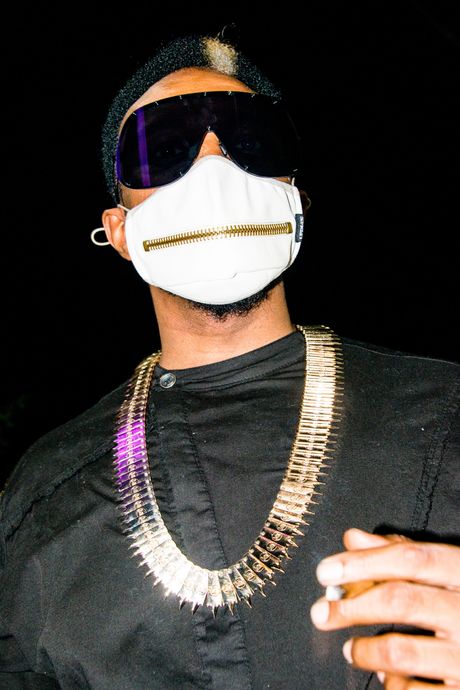

Those who chose to flout the restrictions replaced the official guidelines with their own, based on some mixture of fear, selfishness, proclivity for danger, and digestion of scientific fact. Some adhered to frequent testing regimens or kept their partying outdoors; others relied on gut instinct to determine what was safe. And still others had strict boundaries, only to abandon them as the night wore on.

Not every COVID party skirted the rules: There have been plenty of perfectly legal places to spend your weekends (much to the rage of public-school parents whose children were just forced to go fully remote), like the gay bar, the straight bar, and the Latin restaurant I recently passed in the span of two blocks whose unmasked guests were spilling onto the sidewalk. According to a Washington Post analysis, the reopening of bars, on average, leads to a doubling of COVID cases in three weeks. Like the outdoor park hangs, bars aren’t perceived as real parties, even when they too involve unmasked dancing and boozed-up bodies crowded together. The pandemic party’s definition has been flexible, depending on your own personal COVID boundaries and how judgmental (or jealous) you are of those who flout the rules.

In October, 28 people faced charges after two warehouses were shut down for hosting costumed Halloween raves, one with 400 people in Brooklyn and the other with 550 in the Bronx. After that weekend, the New York Times wrote, “It was not clear if organizers failed to understand or simply ignored the dangers of large indoor gatherings.” But by “Joechella,” when New Yorkers dropped their chaste Saturday plans to celebrate the election results, few in the city could say they hadn’t at least dabbled in some risky socializing.

The party I find myself at this night isn’t an Instagrammable K-hole for downtown “It” kids. This party is shadier and danker. A Prohibition-style gathering of people who believe partying is not a pastime but a sacred right: electronic-music groupies and techno junkies who are here to dance, listen to the music, and forget about the state of the world for a few hours. The organizer, a mysterious online entity who promises a “collective techno and house music community” on the page @newyork_afterhours, has an Instagram full of posts like “YOU GOTTA FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHT TO PARTY!” and “TECHNO IS NOT WHAT I DO. IT’S WHO I AM.”

“Most people go out to meet people or stand around. I’m actually out dancing,” says a young 20-something man taking a sweaty break on the patio. A zealot for this alternate lockdown reality, he has been going out for the past three months, risking it every weekend for the sake of the music. For the most part, he says, the parties he attends are not 500-person blowouts but closer to this size of 70-or-so people. Tonight, he brought along a date, a 21-year-old blonde clad in a skimpy white crop top and Chuck Taylors. She moved here from Russia last year, and they met when he slid into her Instagram DMs.

“I just said, ‘Do you want to go out dancing in Brooklyn?’ ” he explains of their e-meet-cute.

“Here we are,” she replies. “I hope you’re not a murderer.”

“I only kill it on the dance floor,” he coos.

As for personal safety, he tells me there’s nothing to worry about. He is sure to maintain social distancing, though it’s unclear what exactly that distance is as we chat side by side. His date, when asked why she feels safe surrounded by an alarming number of unmasked bodies, says, “I don’t know. My intuition, maybe? I hope it works.” And, quite honestly, she says she was expecting the party to be a lot bigger than it is. “Last weekend, I would say I had more fun, because I was out so late,” her date says, in an attempt to temper her expectations. “But the night’s not done yet.” Every night brings a palpable pressure to have fun, especially when there’s no other spot to check out around the corner, and who knows for sure if there will be a next time?

We’re interrupted by a blitzed man in a top hat who stumbles through several people to ask if we have any matches. In return for a light, he offers us a little rap about his current political stance: “I’m an anarchist. I believe Donald Trump is the worst thing that happened to gambling. Either side, I take the purple pill. I’m sorry, I’m outside of politics. The president doesn’t run my life, my state, and my species, or my life. My state is the shit … Suck my whole dick. I don’t give a fuck.”

If the backyard feels uncomfortably crowded, although admittedly not so different from having drinks at an outdoor bar, the inside of the party feels like pandemic porridge. The patio is on a strict five-minute rotation to prevent the noise from attracting attention and because the dance floor is the kind of place you want to escape from every few minutes since it’s so damn hot — a testament, I’m sure, to the exceptional ventilation.

Out of those dancing and drinking to the oomph-oomph-oomph of the music (“We wanted house,” someone whines), I can spot only two partygoers wearing masks, but one of them is the same man from outside. Around the edges, people do the things you do in the less congested spots of a party. Two fratty-looking white guys in matching white tees and baseball caps snort coke off the same apartment key. A dreadlocked dude lounging on a stairwell takes a rip off his hookah. Someone else takes his shirt off and makes out with the girl he’s dancing with. The high-ceilinged, skylit room is huge, big enough that it might not even be at quarter-capacity, but everyone is squished into a pulsating blob around the DJs.

Unofficial security people keep an eye on the entrance. At the back of the room, two women watch over a bar fit for a college basement party: two card tables, an empty White Claw box holding tips, and an assortment of well-quality liquor, soda, and juice mixers. Someone inexplicably serves me a vodka-and-orange-juice. Someone else tells me the bar is in the corner so it can be dismantled covertly should the police arrive.

At the entrance, more security guards block a sliding door to a vestibule where a guy is demanding $40 cash to come inside, “No ins or outs.” This isn’t a bad price. Some rave backrooms cost $80 and up, not including the price of drinks, which might be $9 or $15 for the same vodka-and-soda. Kristina Alaniesse, a longtime event promoter who became known over the summer for exposing these events, citizen-journalist style, on her Instagram account, says the parties are a fairly lucrative business, and it has attracted upstarts. “The bigger promoters are actually not throwing parties,” Alaniesse says. “I don’t want to seem like a snob, but I know everyone in nightlife and those people are definitely not big shots. The most serious people, the most serious DJs, they do not take the gigs.” Unlike the less-prominent party organizers, they have a reputation to lose. “They’re responsible people,” says Alaniesse. “If you have a real spot, you lose your liquor license. It’s on your record.” Thus the opportunity fell to these lesser-known pandemic profiteers. By Alaniesse’s estimates, there are between ten and 15 parties on any given weekend, with the largest warehouse-style events in Brooklyn and Queens, and the smaller, more exclusive ones in downtown Manhattan. “It’s on fire on the weekends, every, every, every weekend in Brooklyn,” she says.

Newbies or no, this party seems no different than any pre-pandemic rave. People are dancing, their bodies awkwardly oriented toward the DJs. The music is loud. And two very drunk girls are drawing attention to themselves. But according to a bubbly woman in leather pants who stumbles across the room to tell me she loves my outfit, this party is kind of a letdown. “Parties at the beginning of the year were better,” she tells me, reminiscing about a 450-person event she attended that was busted for drugs and solicitation. She’s here with her boyfriend, whose hand I just shook, and gets tested every four days to ensure she can keep dancing and keep her job. (Turns out, she’s a Department of Health employee.) “They’re all people I know here, and also I have the antibodies,” she semi-explains, when I ask why she feels comfortable going out.

It can be hard to find out about your first party, but after you find one, you will get text messages and Instagram DMs and Eventbrite emails about more and more and more. The locations are often kept secret until the afternoon of the party, but a few DMs to the DJs usually means you can find out the location, or at least what borough it’s in, earlier.

An older man in a ponytail sidles up next to me. “Look,” he says, gesturing Lion King–style to the unmasked clump of dancers before us. “This is how people should be.” He proceeds to go on an incomprehensible monologue about the hope he sees in the youth — not for their devotion to solving climate change or anything like that but for their devotion to partying. “I love to party with the gays,” he continues, though this event seems hopelessly straight. Then, in yet another throwback to the trials and tribulations of going out, he puts his hands on my waist and tries to pull me close. Across the room, I spot the one masked man from outside, in a fur-lined jean jacket and a black velvet hat with a peacock feather sticking out of it. “I need you to pretend to be my friend,” I whisper urgently. He puts his arm around my shoulders and leads me outside, commenting on the maskless dancers around us, “People want to be cute, but this is not the time to be cute, bitch! Safety first, bitch!”

Back on the patio, the man, whom I’ll call Samuel, tells me he is a DJ-photographer who just moved from San Francisco to Crown Heights two months ago. “I don’t know anybody out here,” he remarks dejectedly, saying that his pandemic had one silver lining: the reduction in rent prices in Brooklyn. It provided him the opportunity to fulfill the young queer dream of moving to New York City.

This is his third pandemic party, and he has another one planned for Halloween night on a boat. He has been attending them alone, in hopes of meeting “genuine people,” but so far the search has been unsuccessful. “I met some people at my first party, and I thought they were cool. I tried to hang out with them again, and they just kept making a bunch of excuses,” he says. “I met some other people after that through a Tinder date. But then things got kind of weird. And so then … yeah, now it’s just me.”

Like many people I spoke with, Samuel thinks the parties need to happen so the people can just have some goddamn fun in this achingly depressing year. He calls DJ-ing an “art people need,” not unlike “dance or musical theater.” Despite his professed liberal beliefs, he doesn’t see a lot of irony in the scenario taking place around us: young, seemingly lefty people like him who believe in COVID but also possess a libertarian-tinged belief that partying is their constitutional privilege. It’s a collapse of the political spectrum. Bushwick kids and Ole Miss frat boys aren’t that different if their activities are isolated to the wee hours of the weekend.

The politics of partying is something no one here really wants to discuss. Ignoring reality is part of the premise. The 20-somethings sharing spit particles on the dance floor seem to have a generational nihilistic streak, born as they were into a dying world, addled by a bunch of bad shit left to them by their elders. And now, the pandemic. Not to mention that so many young people, despite the virus’s horrifying impact, never forgot those early days of being told they were less at risk. Eight months in, their sense of invincibility has just grown stronger.

Asked whether other people at the party believe in the virus, Samuel says, “That’s a funny question.” He returns to the subject of his mask (which he’s not wearing at the moment, and frankly neither am I), holding it up as the thing that allows him to excuse his own pandemic naughtiness. He doesn’t like to ask the difficult questions. He just wears his mask (sometimes). To him, that’s enough.

Suddenly, the music inside goes quiet and is replaced by the whispering of now 80-plus people. “I think the cops are outside,” says one man. “I see red lights,” says his friend. The supposed man in charge rushes outside to ask about our masks. “Do you have masks? Just in case, because the police are outside. We usually get rid of them pretty well, so just give us a minute. But it’s just in case. We’re all social distancing,” he says, seeming to believe his lie.

Eventually, after several rumors circulate and die, the flashing red-and-blue lights go away, and the music starts up again. I ask Samuel what he thinks happened. “What had happened was some little snitch-ass bitch over here thought that she was special. She thought she could just call 911. And that’s what had happened,” he jokes. I laugh. The two drinks I had earlier have mixed with the vodka-and-orange-juice and the weed pen I am now full-on sharing with Samuel. Although it’s the adrenaline of being six inches away from someone who was a stranger just two hours ago, and relishing that I still remember how to be a person in the world, that has me feeling buzzed.

Will Samuel party again after this? He laughs. “Oh! This ain’t fucking shit. Yeah. Of course. You think I grew up not having police show up to a party?” he says. “Like, fucking oooooh.” Still, we decide to head out as the hour creeps closer to 4 a.m. As my Uber arrives, the same car drops off a new crop of partygoers. “DM me!” Samuel yells.

Afew weeks later, infection rates are spiking in Brooklyn and Staten Island. One weekend, the city is celebrating Joe Biden’s victory in the sunshine, and the next it’s dreading the winter in the rain. For Alaniesse, though, not much has changed. “People are still doing a lot of parties,” she says, when we speak again early in November, after the city instituted a ten-person limit on private gatherings. “I don’t think that’s really going to calm them down.” If anything, she believes, recent crackdowns by the police are more of an incentive to be covert. Even as U.S. cases skyrocket, nervousness about the virus’s spread, she says, doesn’t factor into the party planning. Indeed, the same weekend in mid-November that Governor Cuomo reduced gym, bar, and restaurant capacity and closed bars an hour earlier — which Alaniesse thinks will only encourage illicit partying — the sheriff’s office shut down a 200-person party in Manhattan, a 200-person party in Brooklyn, and a fight club in the Bronx.

The police did not, however, shut down a surprise party for Brooklyn construction boss Carlo Scissura that same weekend, where dozens of the city’s power brokers, including the deputy Brooklyn borough president and Brooklyn’s former Democratic Party chairman, had gathered maskless and indoors. The following week, the city finally hit the 3 percent positivity threshold that would close public schools again, even as indoor dining at reduced capacity remained legal.

As for Samuel, he made it to the Halloween party on the boat. It was supposed to embark on the Manhattan side of the Hudson, but at the last minute, onboarding was relocated to an obscure parking lot in Jersey, which he scrambled to find. “It gave me an old-school renegade feel,” he tells me later. He estimates there were 200 people on the ship, which stayed out until 6 a.m., with house music on one floor and “super-dirty, dark techno” on another. “It was super-lit and super-interesting to see people dancing so freely,” he says. “You got to forget about things for a bit.” Still, even he has decided to give in to caution for the time being. “I’m probably going to wait until, like, December, New Year’s, to go out again.” And then, with a little less assurance: “Probably. I don’t know.”

*This article appears in the November 23, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

No comments:

Post a Comment