Art

How Lygia Clark Transformed Contemporary Art in Brazil and Beyond

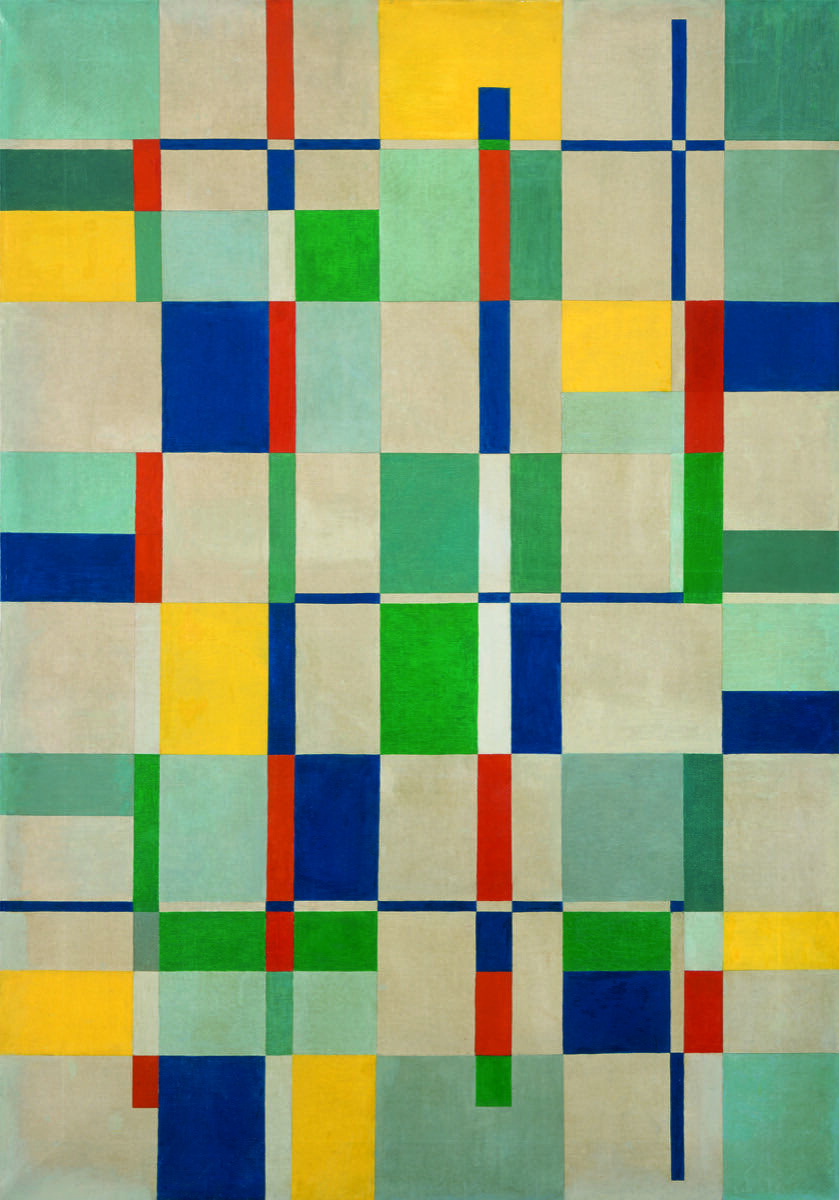

Installation view of “Lygia Clark: Painting as an Experimental Field, 1948–1958” at Guggenheim Bilbao, 2020. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of Guggenheim Bilbao.

“What I wanted was to express space itself, not to compose within it,”

said in 1959. In succeeding, she liberated what she saw as the “dead” picture plane from the wall, giving it unprecedented meaning.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the famed Brazilian

’s birth (she died in 1988). To celebrate her legacy, three international solo exhibitions will take place this year: One, which recently opened at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (through May 24th), will then open at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice on June 27th; those presentations will be followed by “Lygia Clark: Centenary,” opening at Alison Jacques Gallery in London on October 7th.

The artist, who was a recipient of the Guggenheim International Award in 1958 and 1960, is being celebrated by the institution in “Lygia Clark: Painting as an Experimental Field, 1948–1958,” curated by Guggenheim Bilbao associate curator Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães. It covers the decade when Clark switched from figuration to the exuberant abstractions inspired by her teacher

, then to the geometric language that led to Neo-Concretism and beyond. It is divided into three chronological groupings that, together, contextualize pivotal works in the artist’s development—including seldom-seen examples of the virtuoso handling of color that Clark gradually abandoned.

A concrete context

Lygia Clark, O Violoncelista (The Violoncellist), 1951. Private Collection. © Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Lygia Clark, Composição (Composition), 1951. Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. © Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

The artist emerged from a Brazilian modernist tradition spawned earlier in the 20th century, in dialogue with Cubism and

, by the likes of

,

, and

, the latter of whom, like Clark, had studied with

in Paris. Though progressive, modernism in Brazil had been, until the 1950s, largely figurative, favoring themes assertive of national identity, or brasilidade. After growing directionless in the 1940s and then being influenced by the industrialization catalyzed by World War II, artists turned to the geometric abstractions proposed by the European vanguards. The building of Brasília, an entirely new and futuristic capital inaugurated in 1960, defined the national aesthetic and the political zeitgeist of that progressive era.

In that context, Clark adopted a Concretist language shared with the São Paulo–based Grupo Ruptura in the early 1950s, which had no connection to the exotic stereotypes of Brazil abroad. The group idolized

and his grids, and embraced

’s “Concrete Art Manifesto” from 1930, which dictated that “the work of art must be entirely conceived and shaped by the mind before its execution. It shall not be informed by formal references to nature, sensuality, or sentimentality.”

Lygia Clark, Escada (Staircase), 1951. Acervo Museu de Arte Brasileira – MAB FAAP, São Paulo. © Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Lygia Clark, Composição (Composition), 1953. Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. © Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Two years after the 1952 Ruptura manifesto and exhibition in São Paulo, Clark and her carioca peers formed Grupo Frente in Rio de Janeiro, which included

and

. In 1959, they fully split into the Neo-Concrete movement as a reaction “to the Concrete art pushed to a dangerous rationalist exacerbation,” as they wrote in their manifesto. From there, Clark’s unique approach led to her contribution to the history of art: dismantling the two-dimensional picture plane in a way that was organic, devoid of front or back and inside or outside, integrated with its environment, and above all, as art historian Mário Pedrosa put it best, “phenomenologically affective,” rather than purely sensorial.

Clark turned the spectator into an active participant and displaced the focus from the non-object, as it were, to the unique experience engendered by it when activated. “It is not an artwork, but rather the moment of the act, of feeling that is important, nothing more,” she said. The approach discarded all cultural references needed to affect an experience and added the element of time. Its full expression resolved a conceptual challenge artists had grappled with since the Cubists began exploring the fourth dimension.

Following the organic line

Installation view of “Lygia Clark: Painting as an Experimental Field, 1948–1958” at Guggenheim Bilbao, 2020. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of Guggenheim Bilbao.

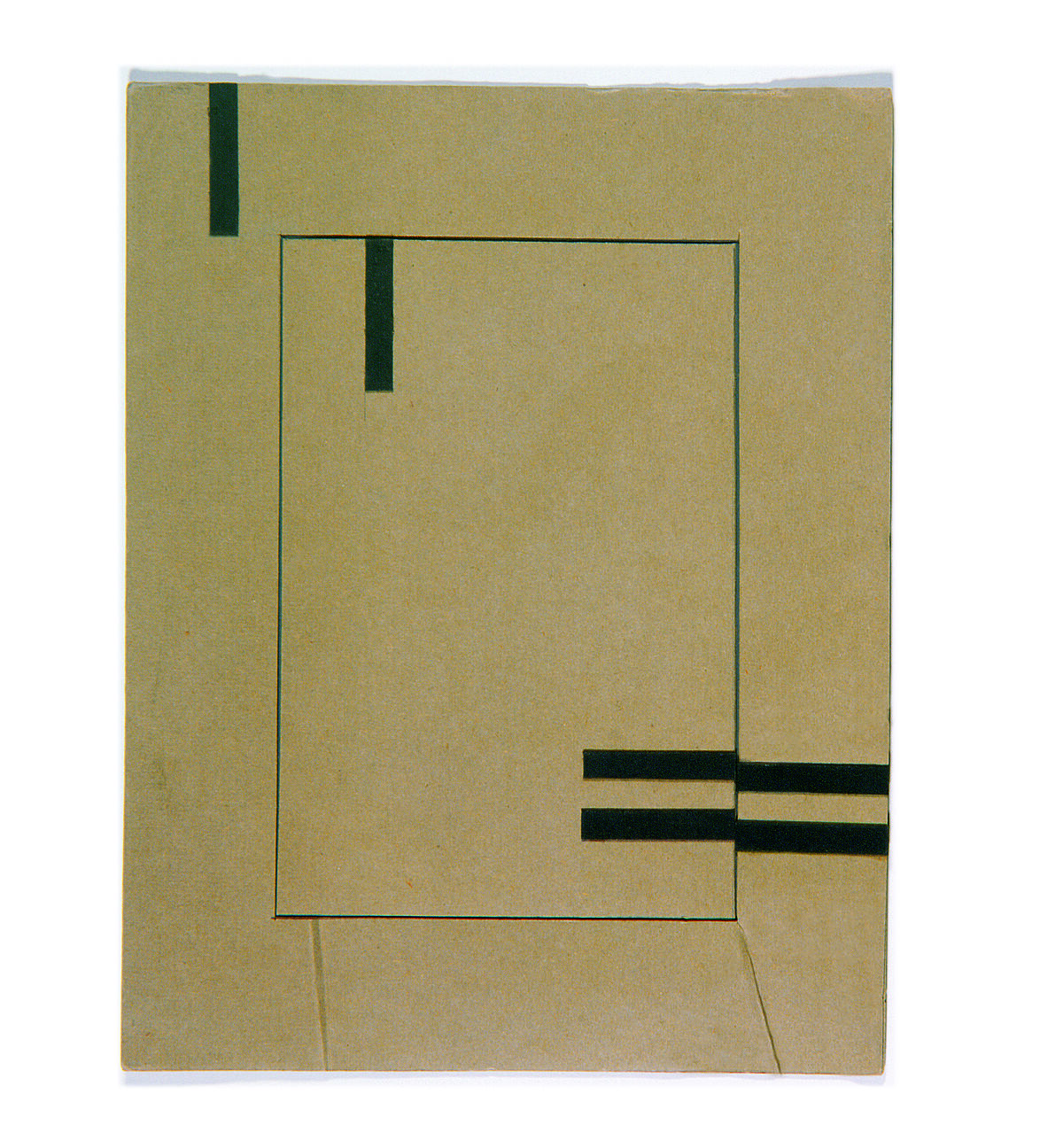

Clark made her breakthrough in 1954, when she became aware of what she termed the “organic line” (linha orgânica) that separated the picture from its frame, claiming the latter, including its seams, as part of the pictorial surface. This set off the deconstruction of the flat vertical plane and the outward expansion that progressively unfolded into her modular and interactive series “Bichos” (“Critters,” 1960–66). From 1963 on, the artist would push phenomenology further in propositions like the breakthrough Caminhando (“Walking,” 1963), the series “Nostalgia do corpo” (“Nostalgia of the Body,” 1966–69), and the therapeutic “Estruturação do self” (“Structuring of the Self,” 1976–88), whose sensorial and relational objects induced alternate perceptions of space-time (espaço-tempo), a concept that is at the core of Clark’s oeuvre.

The artist’s extended sojourns in Paris (1950–52, 1964, and 1968–76) helped bolster her international reputation, as did her 1965 solo show at Signals Gallery in London and her presentation at the 1968 Venice Biennale. At the latter, she was one of the artists representing Brazil, exhibiting a whopping 82 works, including 30 “Bichos” plus the large installation A Casa é o Corpo: penetração, ovulação, germinação e expulsão (“The House is the Body: Penetration, Ovulation, Germination, Expulsion,” 1968).

Clark’s global profile also received a boost from referential exhibitions that aligned her work with

,

, Constructivism, and other canonical modernist traditions. They began in 1960 with

’s “Concrete Art: Fifty Years of Development,” held at the Helmhaus Zürich, where Clark was featured alongside 113 artists including

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and others—only nine of whom were women and, of those, four of whom were Brazilian. Such shows ultimately positioned Clark as the legitimate heir and advancer to Mondrian, Van Doesburg, and Bill’s Concrete tradition—the vital link between intellectual, contained, and organic, affective geometry.

A global art star

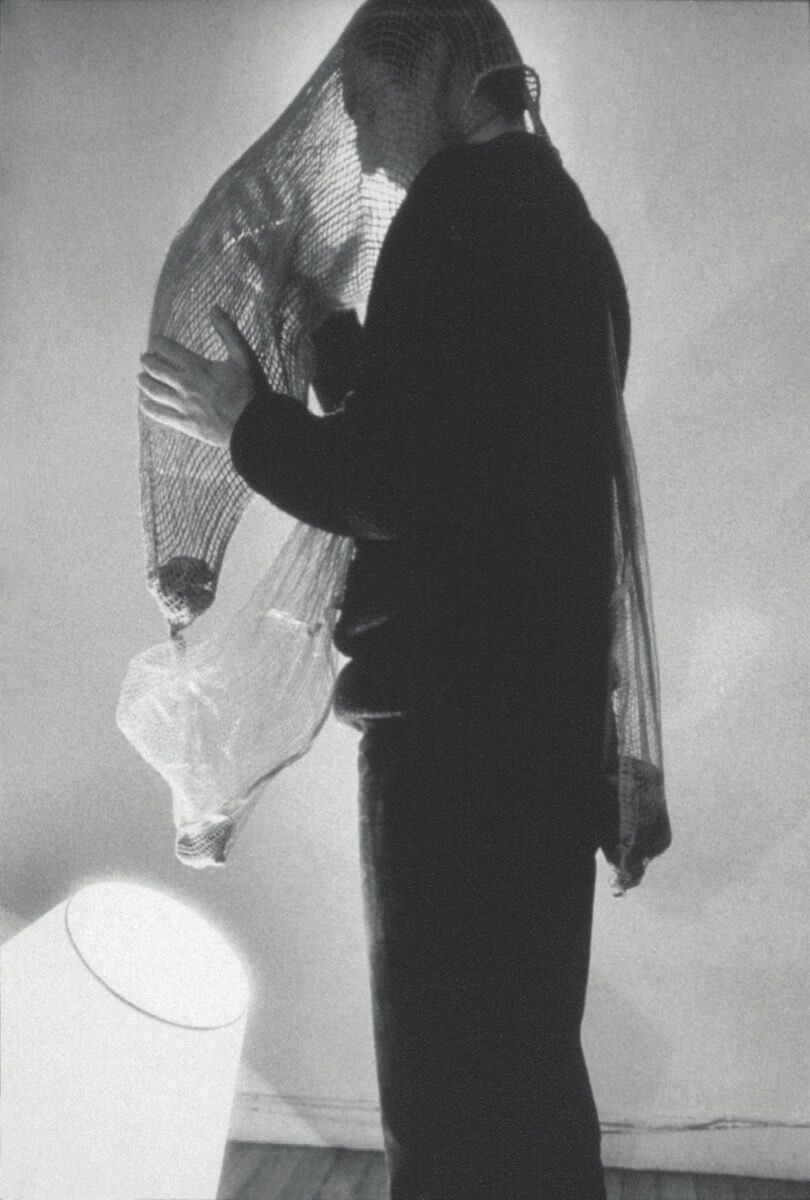

Lygia Clark, Nostalgia of the Body (Nostalgia do Corpo), 1960s. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Lygia Clark, Abyssal Mask (Máscara Abismo), 1969. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Clark’s international recognition grew amid the rapid globalization that began in the late 1980s, advancing a more inclusive history of art that was geographically and culturally diverse, and that was beginning to champion gender equality. “Modernidade. Brazilian Art of the 20th Century” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1987–88—conceptually led by art historian and curator Aracy Amaral, working with team heads Yves Mabin and Maria Luiza Librandi—inaugurated a string of international exhibitions highlighting Brazilian art from the latter half of the 20th century. Clark was prominently featured in the catalog and installations as she invariably was in other group shows such as “Brazil Projects” at MoMA PS1 in New York (assembled by Chris Dercon, Alanna Heiss, and Win Knowlton with Sociedade Cultural Arte Brasil) in 1988 and the Hayward Gallery’s “Art in Latin America: the Modern Era, 1820–1980” (curated by Dawn Adès with Guy Brett), which opened in London in 1989 and was a massive undertaking that had “not been attempted in Europe before,” as Adès wrote in the influential catalog. “Art in Latin America” and “Modernidade” were part of similar large initiatives that continued toward the turn of the millennium in Europe, commemorating its 500-year-old links to Latin America. They had the cumulative effect of firmly writing Neo-Concretism into the history of Latin American and post-war art, and anointing Clark its queen.

A trio of major retrospectives—at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona in 1997, the Itaú Cultural in São Paulo in 2012, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2014—raised her global status further still. The latter exhibition, “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988,” curated by Connie Butler and Luis Pérez-Oramas, was the most momentous, canonizing the artist in the world’s leading modern art museum. Clark is now a regular fixture at MoMA; she most recently took pride of place in the group show “Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction — The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift,” curated by Inés Katzenstein and María Amalia García with Karen Grimson.

The market takes notice

Installation view of “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988” at MoMA, 2014. © The Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Thomas Griesel. Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY and “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Along with institutional recognition, Clark’s international market woke up at the turn of the millennium and exploded a decade later. Her prices climbed rapidly from her auction debut in 1998, when a superlative Bicho from 1960—estimated to sell for a figure between $20,000 and $25,000—fetched $29,900 at a Christie’s sale in New York. Important milestones in Clark’s market rise, both also in New York, include Gagosian’s 2007 exhibition “Beneath the Underdog,” which featured Clark alongside

,

,

, and others, and “Playing with Form: Neoconcrete Art from Brazil,” the first gallery show of the movement in New York, held at Dickinson Gallery in 2011. Clark took center stage in the installation and a Bicho was featured on the catalog cover.

Her auction results peaked in 2013 with a combined total of $4.9 million in sales, which includes the current record of $2.2 million for Contra Relevo (Objeto N. 7) (“Counter Relief (Object N. 7),” 1959), realized at Phillips in New York. Since then, three “Bichos” have crossed the million-dollar mark in public sales. But from 2015 to 2019, only two of the four works by Clark offered at auction actually sold—the results, in the end, returned to 2003 levels.

Portrait of Lygia Clark, 1960s. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association.

Lygia Clark, Planes on a Modulated Surface No. 5 (Planos em superfície modulada no. 5), 1957. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and The Adolpho Leirner Collection of Brazilian Constructive Art.

While auction results lend some clarity to Clark’s market, sales from gallery shows and art fairs are far murkier. Some of the most important “Bichos” can be priced around $3 million by galleries. The aluminum finish plays a special part in their value—anodized golden, because of its rarity, adds to the price. In 2010 already, Natalie Seroussi had sold one for $700,000 at FIAC in Paris, while in London that same year, another was sold at Phillips for £367,250 ($565,444). Just last year, another Bicho (1960) sold for $1.4 million at Galeria Bergamin & Gomide.

The São Paulo–based gallery previously sold Espaço modulado 3 (“Modulated Space 3,” 1959) for $1.8 million in 2015 and Casulo (“Cocoon,” 1959) at TEFAF New York in spring 2019 for $1 million—the only work from the “Cocoon” series at auction realized $437,000 in 2013. The gallery also sold Unidade IV (“Unity IV,” 1959), a piece from her series of seven small black-and-white works on wood panel, for $807,000 in 2019. To put that result in perspective, Unidade V and Unidade VI fetched about $25,000 to $30,000 each at auction in 1999. In 2014, Unidade I sold for $461,000 at Phillips in New York, later resurfacing in the Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection.

Installation view of works by Lygia Clark and Jesús Rafael Soto in Galeria Bergamin & Gomide’s booth at TEFAF New York Spring 2019. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Photo by Mark Niedermann. Courtesy of TEFAF.

The main lesson to be learned from Bergamin & Gomide’s private sales of Clark’s work is that they line up with her second-best year at auction, 2014, but far outpaced her total value at auction in 2019—about $128,000—adding up to $3.2 million. (The latter figure may not even include all of the gallery’s Clark sales last year.) The gallery’s tremendous $1.8-million sale from 2015 also happened in a year when none of her work went up for auction. These are select results from one gallery, albeit a very active one with some of the best stock and supplier liaisons, and one that participates in all the key fairs. Additional sales data from the other galleries handling Clark’s work would likely dwarf what’s been achieved at auction.

London-based dealer Alison Jacques was the first to secure international representation, in 2010, working with the estate and institution Associação Cultural O Mundo de Lygia Clark (a.k.a. the World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association). The dealer recalled thinking that Clark “was groundbreaking and a real pioneer and wanted to see more of her work outside of Brazil.” Jacques said the 2014 MoMA retrospective “was the absolute pinnacle of curatorial recognition we could have hoped for Lygia,” and that her market “remains strong with recent sales of ‘Bicho’ sculptures around the $2-million mark.” These, “which range in size from small to medium, sell from $1.2 million up to $2.5 million,” she added. For the 2013 edition of Art Basel in Basel, Jacques commissioned a 23-foot-tall “Bicho” from Clark’s unrealized, monumental series “Arquitetura fantástica” (“Fantastic Architecture”) of 1963 to greet visitors to the fair’s Unlimited section. It rallied anticipation for the MoMA retrospective the following year and made a memorable statement just three weeks after her record-breaking auction result.

Galleries get in on the act

Lygia Clark, Quebra da Moldura (Breaking the Frame), 1954. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of Alison Jacques Gallery, London.

Lygia Clark, installation view of Fantastic Architecture I, 1963/2013. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. Courtesy of Alison Jacques Gallery, London.

The groundswell of institutional and market attention garnered by Clark’s work in the 2010s has led to a major uptick in gallery interest. In New York, Luhring Augustine joined representation with Jacques and the World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association in 2017, hosting the artist’s first solo gallery show in the city since 1963. On the international fair circuit, São Paulo–based galleries Bergamin & Gomide, Galeria Raquel Arnaud, Dan Galeria, and Galeria Luisa Strina, along with Paris-based Natalie Serrousi and, more recently, the mega-gallery Lévy Gorvy, constitute the main secondary representation for the artist.

Donald Johnson Montenegro, senior director at Luhring Augustine, said the gallery recently placed Bicho Pássaro do Espaço (“Critter Bird in Space,” 1960) and two related works with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “The study and the final ‘Bicho’ were acquired by the museum,” he said. “The maquette was purchased by a private collection as a promised gift to SFMOMA. All three are currently on view.” With these acquisitions and promised gift, SFMOMA became the first institution to be able to chronicle the entire three-stage development of a single “Bicho.” Montenegro said the collectors and museum representatives saw all three pieces at the 2019 FOG Design+Art fair, where the gallery presented a two-artist stand pairing works by Clark and

.

Installation view of works by Lygia Clark and Oscar Tuazon in Luhring Augustine’s booth at FOG Design+Art, 2019. © “The World of Lygia Clark” Cultural Association. © Oscar Tuazon. Photo by Johnna Arnold and Impart Photography. Courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York; Alison Jacques Gallery, London; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; and Eva Presenhuber, Zürich / New York.

Even though Clark had her biggest flop at auction ever in 2019—when O antes é o depois (“Before is After,” 1963), with a high estimate of $1.2 million, went unsold—her private market remains strong, with top representation and results. The “Bichos” and a handful of other series regularly command seven-figure sums, while others are still climbing the hundreds of thousands. With this year’s centennial exhibitions, we are sure to see more of the artist everywhere, except perhaps at auction, where her best offerings have dwindled. Despite fluctuations roughly corresponding to major institutional exhibitions, Clark’s market has leveled off comfortably since the steep increase in the years preceding MoMA’s 2014 retrospective. Her status—both in art history and in the art market—is now firmly cemented.

Clark’s “oeuvre is timeless,” said Alessandra Clark, the artist’s granddaughter, who is involved in the World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association. “It works independently from political, religious, or social movements. [She] was guided by mental survival, which particularly resonates in the world today.”

Luciano deMarsillac is the Head of Fair Tours at TEFAF New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment