Photography and the Art of Looking

Darran Anderson explores the complex dynamics of the gaze between artist, subject, photographer and viewer

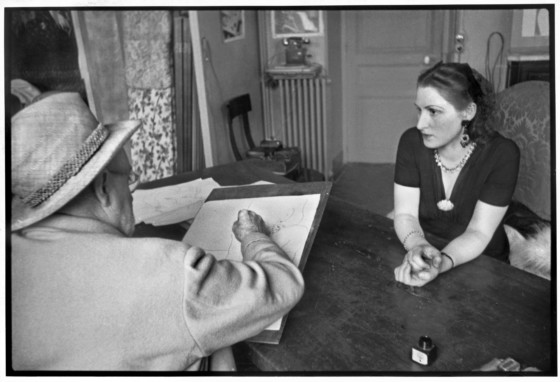

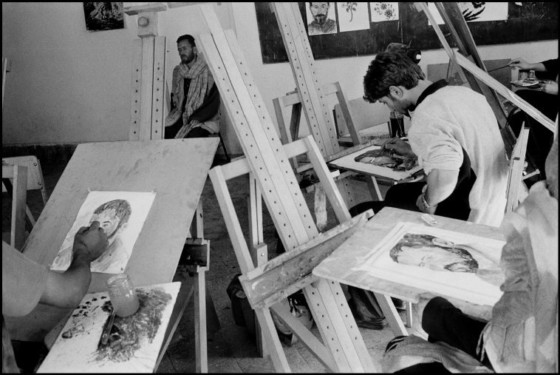

Eve Arnold Art Class. Chongqing, China. 1979. © Eve Arnold | Magnum Photos

License |

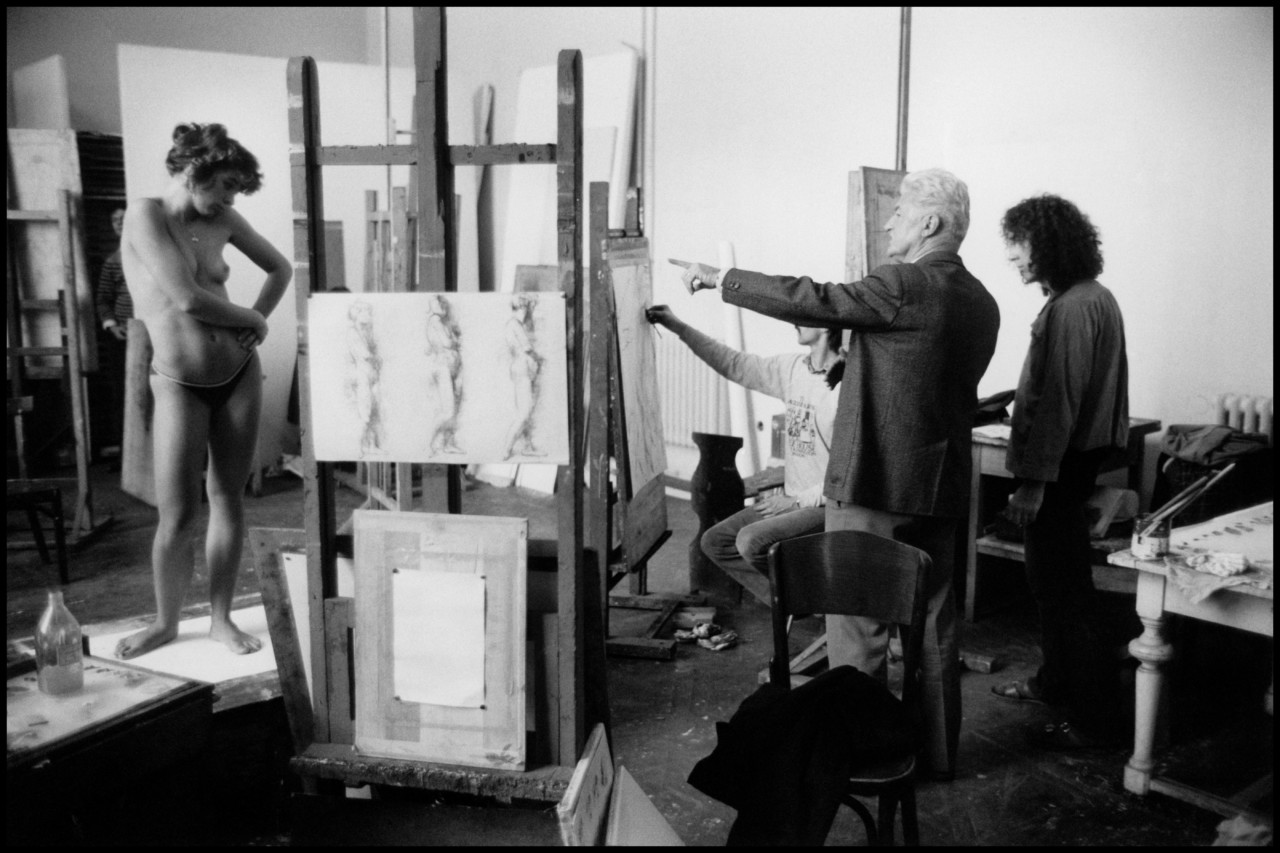

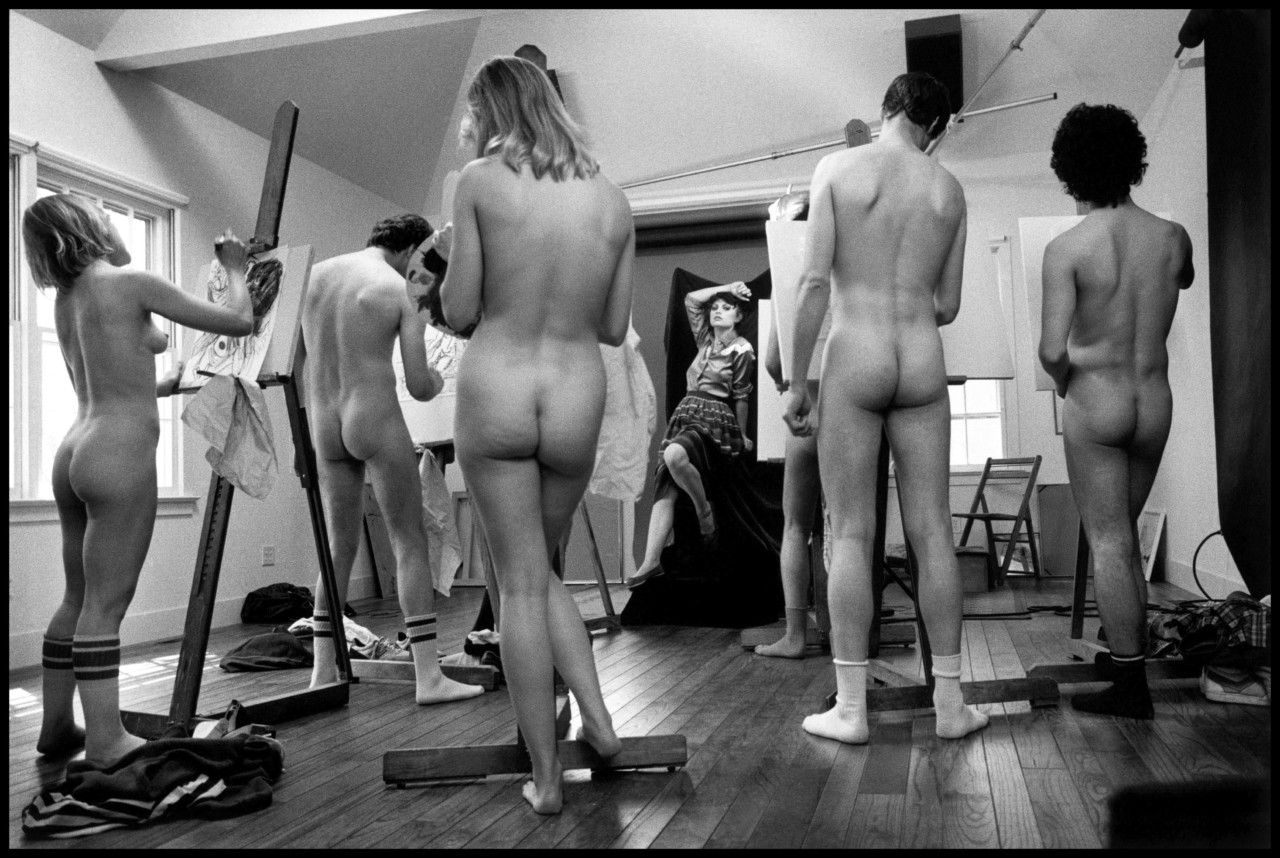

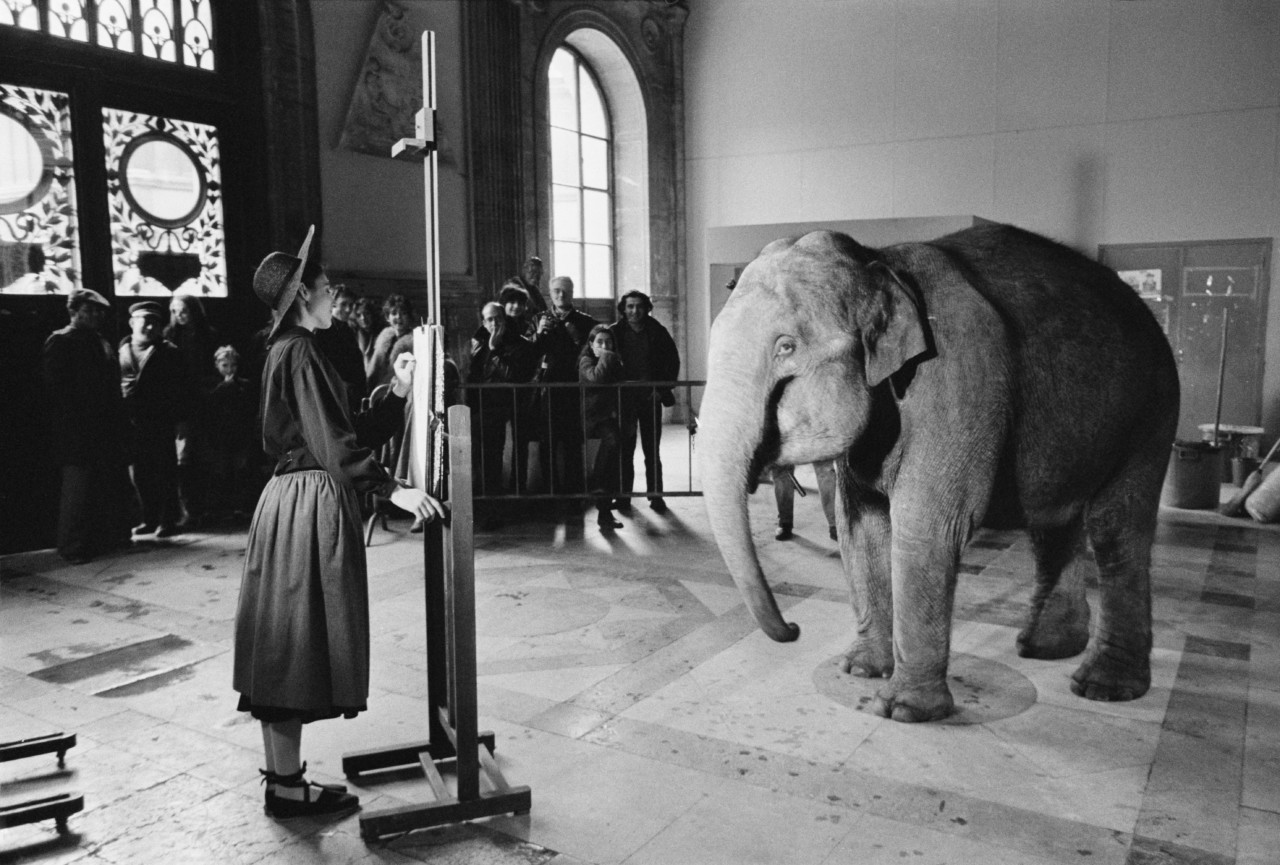

Leonard Freed Art School. Budapest, Hungary. 1985. © Leonard Freed | Magnum Photos

License |

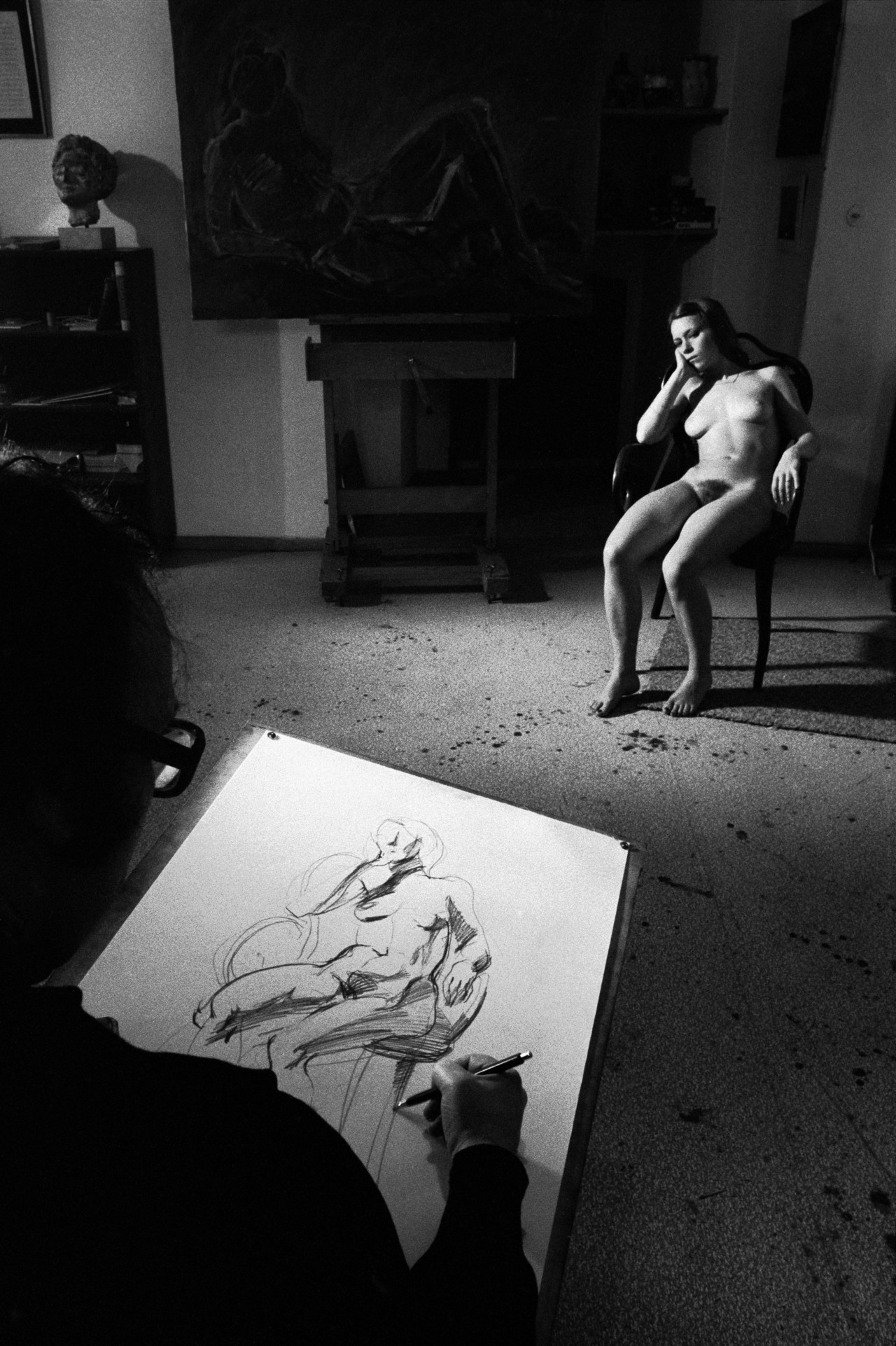

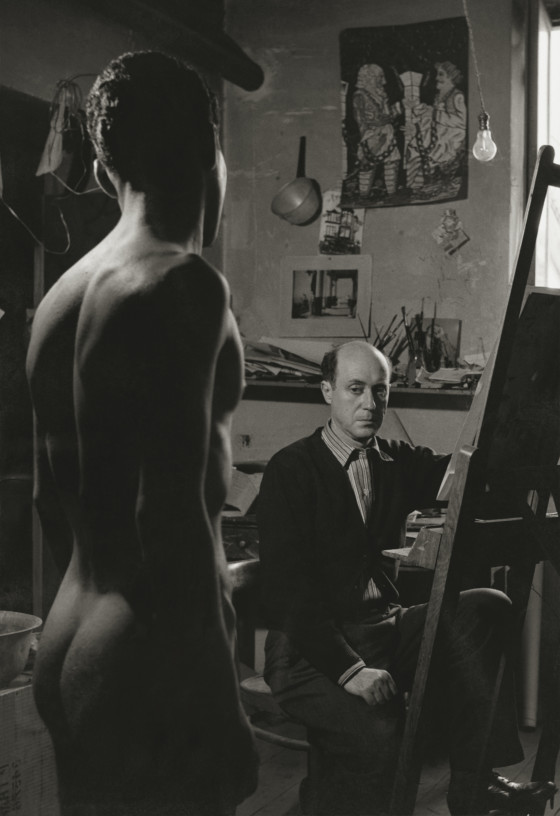

Erich Lessing © Erich Lessing | Magnum Photos

License |

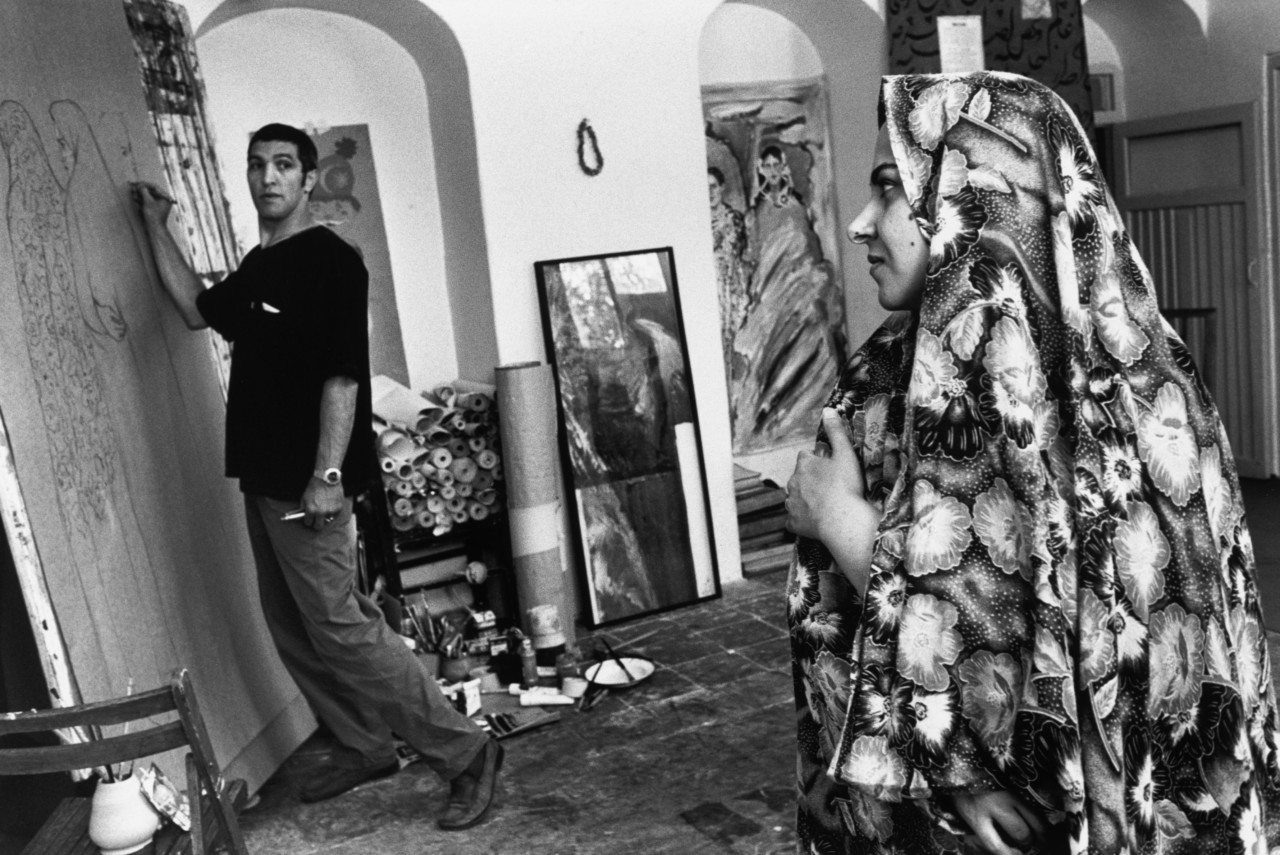

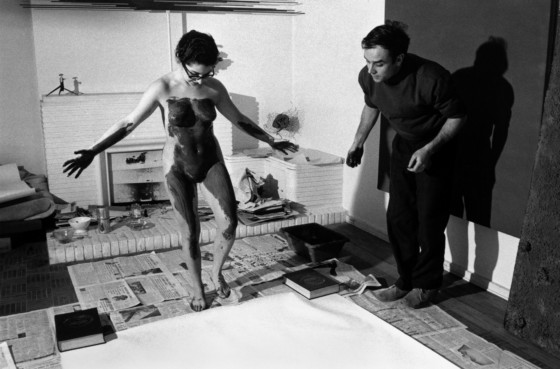

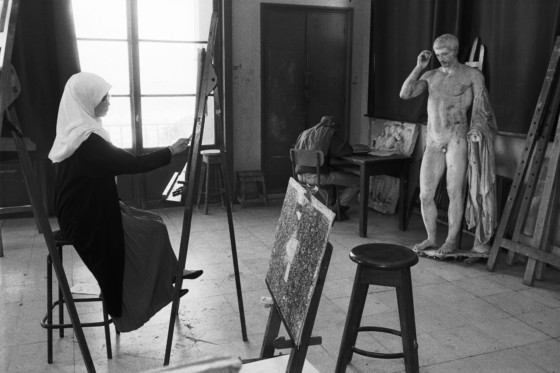

Abbas Ashraf is a model to her husband, modern painter Khosrow Hassanzadeh, in his studio. Tehran, Iran. May 2001. © Abbas | Magnum Photos

License |

"You do not need to know that he depicted her almost a hundred times, that they fled the Nazis together, that he drew her on his deathbed, to sense the connection in her stare, open, affectionate and penetrating"

- Darran Anderson on Henri Matisse and Lydia Delectorskaya

Elliott Erwitt East Hampton, New York, USA. 1983. © Elliott Erwitt | Magnum Photos

License |

Rene Burri A model poses as an artist for a fashion shooting, in the hall of the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Paris, France. 1981. © Rene Burri | Magnum Photos

License |

"At the heart of these images we find not just the intense study of who we are but the artifice involved"

- Darran Anderson

Thomas Hoepker Modelling class. The Korean National Academy of Arts, a new college campus for the arts (theater, dance, performance, traditional music, painting and sculpture). Seoul, Korea. 2007. © Thomas Hoepker | Magnum Photos

Abbas Home of photographer Mario Cravo Neto. Salvador, Bahia state, Brazil. 1996. © Abbas | Magnum Photos

License |

"There is little doubt that we are performers and watchers but it’s also telling that we reveal who we are when we think no-one is looking."

- Darran Anderson

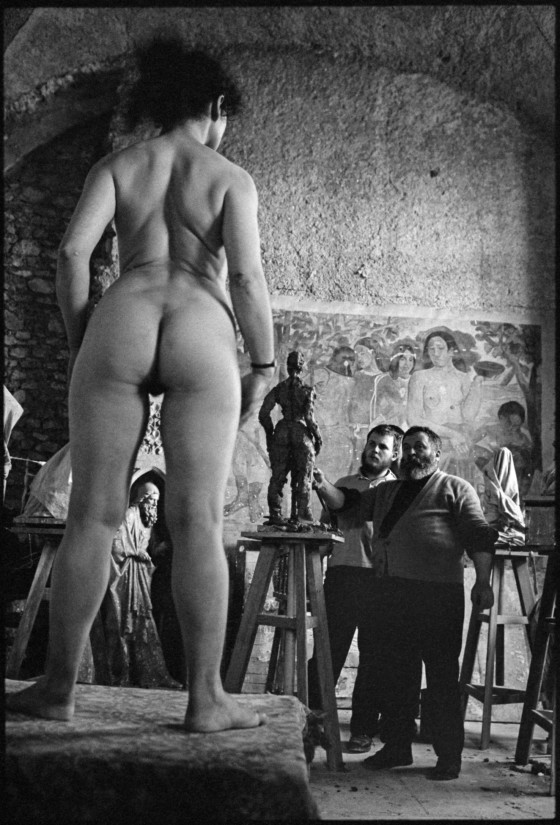

Burt Glinn Snaps of nude model Virginia Campbell-Buller in the studio of painter Casey Van Duren. This is a basement studio in the heart of North Beach. She is a native of England but has been in the US for 1 (...)

License |

No comments:

Post a Comment