The Big Interview

The Story of artnet, Part 3: How Hans Neuendorf Cornered the Market on Baselitz and Picabia, and Started a Lucrative Art Fund

In the third part of an interview series to mark artnet’s 30th anniversary, Hans Neuendorf talks about his adventures in the 1970s and ’80s.

Imagine a time when the art market was up for grabs—when everything was new, when masterpieces were not too difficult to obtain, and where a little charm, a little industry, and a lot of luck could make even modest art dealers into significant players on the world stage. This, it seems, is what the heyday of the 1970s and ‘80s were like for Hans Neuendorf, who, before he came to create artnet—and, through it, bring a degree of transparency to the art market—thrived in the rough-and-tumble, handshake-propelled business of betting on artists.

Early on, Neuendorf saw value in the work of Georg Baselitz—an artist who emerged from what was then East Germany with difficult, un-pretty paintings of struggle—and bought it when everyone else was looking the other way. Later, when Baselitz became a sensation, Neuendorf had managed to corner the artist’s market—just as he later did with the great but long-undersung modernist Francis Picabia. He created a successful art fund; he single-handedly brought Sotheby’s to Frankfurt. He did the first Warhol show in Germany, but liked the art better than the man.

Here, in the third installment of an ongoing interview series to mark artnet’s 30th anniversary, artnet News editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein sat down with Neuendorf to discuss this fertile chapter of his life, and hear the stories behind the deals.

When you were starting out, how were the prices of artworks designated? You were saying that you would go to Paris and buy artworks and then sell them in Germany for much higher prices. How did people know what was a fair value?

Pricing information was always the critical point. Nobody knew what anything was worth. So, at the art fairs, people would go around with their little pads, taking notes. Often, they didn’t ask for prices because they wanted to buy something—they asked because they just wanted to know what their collection was worth, or how much they should pay another dealer for a similar piece. Everyone was doing their own pricing research all the time. That’s why I thought it might be good to do a price database.

So one person would have one set of prices, and another person would have their own set of prices. As a dealer, how would you price the artworks you were selling?

Well, you would talk to other dealers and to clients who had been around to other galleries in the market, and somehow you’d have to figure out a price. Then, when something was sold, you would have a firm price point and could start from there. Hockney, as I said, was very hot from the start. Baselitz was an artist who everyone agreed was terrible. Germany was totally overwhelmed by Pop art and Op Art and all this art that was imported from far away. That was the hot thing.

Germans didn’t really believe that their country could produce its own art, even though there were a number of really good, important artists at work in Germany. They weren’t appreciated very much. But then there was Documenta, and that was very revealing to the public. All the German artists were in Documenta. The first, the second, and the third. That had a huge influence on the understanding of the art, and the fact that it was an international enterprise.

An early painting by Georg Baselitz, Mit Roter Fahne (With Red Flag) (1965) going to auction at Sotheby’s. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

You were far ahead of the curve on Baselitz, though.

Nobody liked his work. I thought that Baselitz was so crude and unlikeable—too rough—and I thought something very interesting, something very elemental was there. I sensed there was this great power behind it. I said, “This a good artist, even if nobody likes him.” Then I was in a small gallery, Tobias und Ziegler—they later closed it and opened a store for children’s toys—and they had two paintings in their tiny office that were two and a half meters high. Huge paintings.

One was called Der Mann am Baum abwärts—it’s a green painting of a man in a tree with his head down—and the other one was called Der Blaue Wald. I was squeezed between these paintings, sitting there talking to them about other dealers. And they asked me what I wanted, and I said, “Both paintings.” I don’t know what drove me, but I thought this was so powerful that I must get involved in it.

Were they upside down?

They were upside down. These were two of his very first upside-down paintings—they were very important paintings. How these two dealers, who were a couple, came to have these paintings I don’t understand. Anyway, I bought them, and then I talked to Franz Dahlem, who was promoting Baselitz, and others who were involved in his work, and I started buying them wherever they were. Nobody could sell them, so you could pick them up for very little. And then I wanted to talk to Baselitz. He lived in Forst, on Weinstraße, and I went to see him, and that’s how the relationship started. I did an exhibition of his “Hero” paintings in my gallery in Hamburg—that was a fantastic exhibition, all 23 of the paintings.

Did people buy them?

Well, a professor bought two. And then another guy in Cologne bought two, and a collector who is a photographer ended up buying one. But all at discounted prices, paid over time. It was hard to sell them, but I did sell them. Very few people wanted them.

Now those paintings are considered masterpieces—historic artworks of the time.

He got the idea of the upside-down paintings from Mannerist paintings of the 16th century, like Wtewael, de Gheyn, Spranger, and of course the Italians of the Fontainebleau School. Baselitz had bought a collection of prints in Paris. In the beginning he didn’t make any money, but his wife Elke had started a women’s clothing boutique in the nearby town of Worms, and she supported the family. They went to Paris together by car often, and when she was selling her dresses, he went to the bouquinistes and found these Mannerist prints very interesting. They sold them for pennies, so he bought a whole collection of these things, and built quite an important collection over time.

Some years later, after the prices had gone up, he sold this entire collection in order to make the downpayment to buy his castle in Derneburg. But then Baselitz’s prices went up so fast because he really pushed the prices. Baselitz is very ambitious, and completely ruthless, and a much better businessman than I ever was. Then, when he’d made money himself, he went back to the dealer in Paris who he had sold his prints to and bought the whole thing back for much, much more money. So now he has the collection.

The artist Georg Baselitz at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich in 2019. Photo by Hannes Magerstaedt/Getty Images.

So now, as the market was evolving, and people were starting to make some money, you had an interesting idea: to start an art fund, which you called United Artists. Where did that idea come from?

It came about because I wanted to buy more of Baselitz’s paintings and I didn’t have the money. Also, I couldn’t buy any of the works that I wanted to buy in America. It didn’t make sense to borrow works and ship them to Germany and then ship them back unsold—the cost was too high. It was much better to buy things outright. You can’t operate as a dealer without capital, and I didn’t have any capital. For many years I had operated on a shoestring. So I tried to persuade some of the people in Hamburg who I knew from parties, mostly, or through acquaintances, to give me money. But I needed a structure for that, so I started a company and began selling shares in that company.

There was also a group of people who I was very close to, and one or two of them did give me 50,000 D-Marks, which I had set as a minimum investment, and some gave 100,000. Then the others were persuaded by these first investors to follow through, so it became a self-propelling thing, in a way. They all came in with some money—it wasn’t really very much—but what I did with it was very good, because I bought all these Baselitz paintings. I made out like a bandit with those things. I was also able to buy many works by [Lucio] Fontana with that capital, and Morris Louis, and [Leon] Golub. So I did very well for a number of years. I was very interested in the Italian artists, like Fontana and [Emillio] Vedova. But also [Francis] Picabia.

Is it true that at one point you bought the entire Picabia estate?

No, not the entire estate. His widow wouldn’t part with the entire estate. Ultimately I had the idea that maybe I shouldn’t be too greedy and let her live with the paintings she had on the walls, so I proposed to her to buy everything except what was hanging on her walls. And that worked.

How incredible.

I sold a lot of Picabia. I asked for higher prices than everybody else and I got away with it. It worked very well. I made a lot of money on Picabia. But there were still a lot of paintings available then. Picabia was never a name like Picasso or Matisse—it was always a very special kind of thing, and few people understood what it was. Artists did—[Sigmar] Polke understood his work very well—but others not so much. Then, when I needed money for artnet, I sold all the remaining paintings to Iwan Wirth. He bought the whole lot, and he still has most of them. There were some masterpieces in there, and Iwan’s mother-in-law is the one who has the best paintings from the lot that I sold. She’s very rich, because she built a department store in Zürich. Iwan didn’t have any money when he started. It’s all through the daughter. He’s a smart cookie.

Francis Picabia’s Reclining Nudes (ca. 1939). Courtesy Michael Werner Kunsthandel.

So your fund must have been pretty successful.

Yes, everybody was happy. I called it United Artists because artists, when they’re successful, are making a lot of money, and they just stuff it in the mattress. I thought the artists should start thinking economically and put the money in the fund so that other artists could participate and profit from it.

That sounds like the concept behind the Artists Pension Fund in New York, which has been engulfed by scandals.

Of course it has scandals. It’s a flawed system. It’s bullshit, but they knew that from the start. They never looked at the art. They thought that if you keep an artist’s work long enough, they’ll become valuable. No. Some do, but some of it stinks.

So what happened in the end with your fund? Did everybody make money on their investment?

Yeah. I put an end to it and distributed the money. It was a big success, but why? Because I had my investors under control in such a way that they would not question my investments. It wasn’t necessary for me to justify my acquisition of 30 Baselitz paintings, because they never knew. Had they known about it, they would’ve complained. “You bought this? Are you crazy? That’s a lot of money.” I kept it all undercover—I didn’t tell them what I bought. I bought things that I liked, with an eye to appreciation, but not within a certain timeframe. I just thought, “We’ll promote this artist and keep the pictures.” I had a lot of Baselitz paintings, and then, when I had the contract with him, I had even more. I had his entire inventory, basically, in my storage.

What do you think would’ve happened if you continued with the art fund and just kept expanding it?

I would’ve become very rich. Instead I took my money out and started artnet. Anyway, it was an adventure, just like art-dealing was an adventure at first. Also, I would’ve become a slave to the money. I didn’t want that.

So when did you start coming to New York?

Well, after I did the Pop art show with Ileana Sonnabend, she said, “You must come to New York.” So I accompanied her to New York and she introduced me to all of the artists. I spent my first night on Christo’s green leather sofa. Christo always knew all the gossip, which is why she always went to visit him first thing, to hear about who was going with who and whatnot. He knew about not only the dealers and the artists but also all the women, and so then she knew everything too. She had a great memory for everything. I was really close to Ileana, and I liked her a lot, but she was also close to Gian Lorenzo Sperone and Zwirner. There were other dealers in Germany and in Europe who she used to promote Pop art. Because what she did with her gallery was very strategic. She let Leo run the New York gallery, although she was the brains behind the whole operation—Leo never did anything. But she used other dealers to make a beachhead for Pop art in these other counties.

Did you know the Pop artists too?

Yes, [Roy] Lichtenstein and [James] Rosenquist and Warhol. I did the first Warhol show in Germany—it was the flowers and the cows and the pillows. It was great.

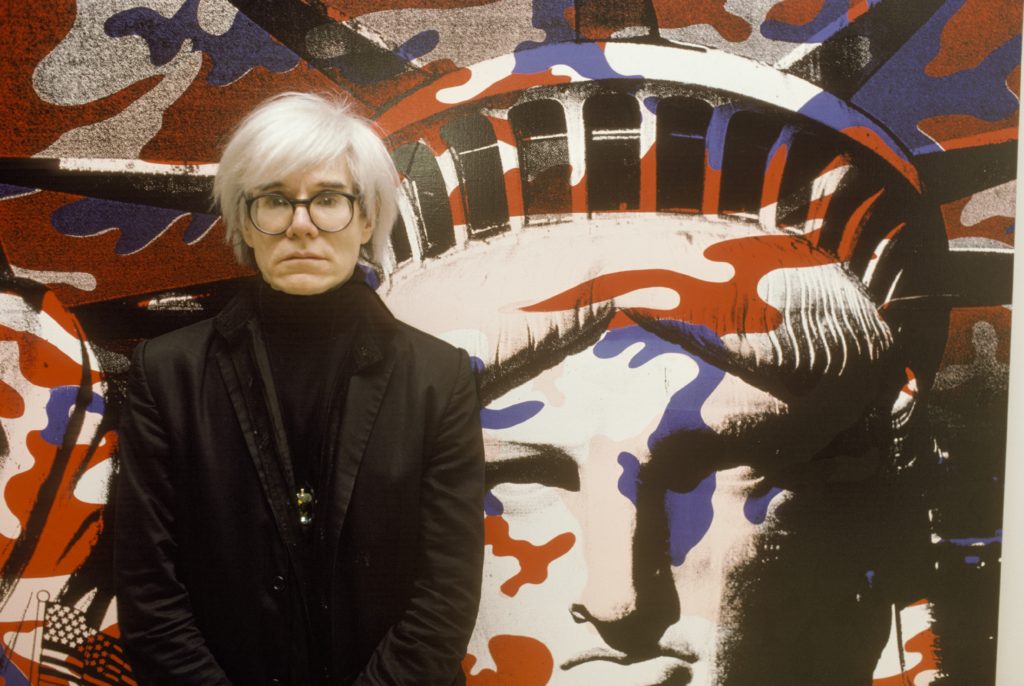

Andy Warhol in Paris, April 22nd, 1986. Photo by Francois LOCHON/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

What was your relationship with Warhol like?

Well, I didn’t deal with him directly—I dealt with Ileana or Leo. I didn’t befriend him as much as Bruno Bischofberger did, or Heiner Friedrich did. I must say I didn’t like the situation at the Factory. There were a lot of really arrogant hangers-on, and it was kind of uncomfortable. I didn’t like it there. But the others put up with it, and I didn’t. My personal relationship with Warhol was almost nonexistent. I was closer to Lichtenstein, who was a very quiet, if also boring, character. And guys like [Robert] Rauschenberg. They were nicer people, I found.

It seems like you never really got carried about by the excesses of the art business.

No.

At the same time, your influence in the art market just continued to grow. Is it true that you were singlehandedly responsible for bringing Sotheby’s to Frankfurt?

Yes, that’s very true.

How did that happen?

There was a building commissioner in Frankfurt, his name was Haverkamp, who played a big role in politics there. And Frankfurt was drowning in tax money, because all the big banks had moved to the city, and all of a sudden they were making huge profits. So, because Frankfurt found itself with so much money, they thought they should create some kind of culture scene there. And this guy Haverkamp called me up cold and said, “Would you be interested in moving to Frankfurt?” I said, “Yeah, why not?” And he said, “We certainly have something to offer you if you want to come. We want to create an art scene and we are inviting some of the bigger galleries here. What would you need?” And I said, “Well, I need a gallery.” He said, “Okay, no problem. What size? Where should it be?” They offered me this huge four-story villa in the best part of town, Beethoven Straße. And I thought, “This can’t be true. Why are they offering this to me?”

But they were gung-ho and wanted to move forward. And I said, “I need exhibition space, and storage, and place where I can put my family can live, but this is far too big.” Then they asked, “Can you think of anyone else who might want to come to Frankfurt?” I said, “If you want to create a culture scene here, you should try to get one of the big auction houses to set up an office here.” Then I called Sotheby’s, and they said, “Yeah, okay.” And they came. I took the first floor for my gallery and the floor beneath it, a basement with windows, for my storage. Then above my gallery was Sotheby’s, and above that was my apartment—and above that was another dealer who came from Vienna, Hilger.

And then they started redoing the building, which had been damaged in the war, and they discovered grave structural problems, and it became a huge, incredibly expensive operation. But I had my own architects design it, Pawson and Silvestrin, who also did my house in Mallorca, and I got what I wanted and I didn’t have to pay for any of it.

The Neuendorf House in Mallorca, designed by Pawson and Silvestrin. Courtesy of the Neuendorf House.

Frankfurt paid for the whole thing? Building the gallery, moving your family—everything?

Yes. Everything.

Wow. All because they wanted to create a cultural hub?

Yes, and there was another upside for me, too, because Frankfurt had nonstop flights to New York, while in Hamburg I always had to switch planes, and I hated that. Also, it was closer to Southern Germany, where there was much more money than up north. Hamburg was really not a very friendly place for selling art. So that’s how we landed in Frankfurt.

What year was that?

It was 1985 or ’86.

Did you like it there? And did they succeed in creating the art scene they hoped for?

No. There was an inbred kind of cultural scene in Frankfurt, with some critics and some artists and all that, and they didn’t want me there. They didn’t like my exhibitions. The press didn’t write about anything I did. I had my Picabia show, which was an important exhibition, and I had my Fontana show in 1987. But the art scene didn’t want me there. They wanted to keep their positions intact, you know? They didn’t want me in the mix. I left after about seven years.

No comments:

Post a Comment