Gagosian Quarterly

April 29, 2019

TIME BY DANCE BY PAIK

Gillian Jakab considers the role of choreography in Nam June Paik’s 1989 video installation Fin de Siècle II.

Gillian Jakab works for La Napoule Art Foundation and has served, since 2016, as the dance editor of The Brooklyn Rail.

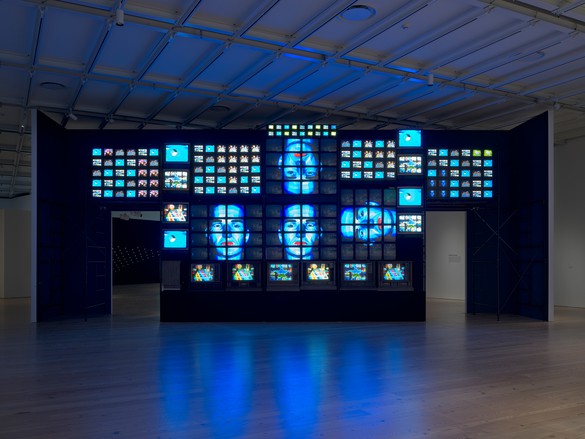

Screens flicker and bodies groove across time in Nam June Paik’s monumental installation Fin de Siècle II (1989). Framed within the displays of more than two hundred 1980s television sets, Merce Cunningham and his sinuous outline momentarily dance a duet. The two figures multiply across the kaleidoscopic screens—some remaining upright, some now sideways—before the footage cuts to a segment of David Bowie performing with dancer Louise Lecavalier of the group La La La Human Steps. In this programmed progression, Paik propels us from 1978-and-before to 1988-and-beyond, from the vanguard of avant-garde dance to pop music performance art, from video as a means of preservation to video where the medium is very much the message.

Time is Paik’s through thread, expressed in the sub-rhythm of the dancers depicted, in the grand rhythm of Paik’s video symphony, in the history and the future conjured by the images, and in the title, which transports us at once backward and forward to the twentieth century’s turns.

The Korean-born artist first fashioned Fin de Siècle II for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1989 exhibition Image World. After a stint in private ownership following the exhibition, the video sculpture returned to the Whitney and entered its collection. A seven-year conservation project ensued—involving the sourcing of vintage consoles and restoration of the work’s seven video channels—before Fin de Siècle II reentered public view for the first time in three decades with the exhibition Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018. While the last category in the exhibition title describes a conceptual frame shared by many of the works on view—choreography as a set of instructions to be carried out at a later time—the dance term is also a nod to the interdisciplinary spirit of the show in general, and Fin de Siècle II in particular.

Working across media, as he did in Fin de Siècle II, had long been an aspect of Paik’s approach. Following training in classical music and formative interactions with modernist composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage in Berlin, Paik became an early member of the pioneering cross-disciplinary group Fluxus. In a 1966 essay, Fluxus co-founder Dick Higgins expressed the term “intermedia” with a utopian fervor, heralding the end of rigid categories and class distinctions.1 Paik’s “intermedia” work comes off as less an echo of this singular political assertion and more an embrace of complexity in a time of myriad, intertwined modes of communication. Though often dubbed the “father of video art,” Paik created work that sprawls far beyond a single medium and explores ways in which art forms can manipulate and mediate one another.2 Time and again we see in Paik the intersections of live performance, broadcast television, sculptural installation, and rhythm, using media new and old.

Dance, while playing a minor role in the grand scheme of his oeuvre, is closely tied to a grand theme in his work: time. Paik’s use of dance—as exemplified by Fin de Siècle II—is both a meditation on time-based art and a reflection of the time in which the work was made, channeling the past and forecasting the future.

Time in Dance and Video Media

The Cunningham footage in Fin de Siècle II is a sampling from Paik’s earlier single-channel video Merce by Merce by Paik (1978). This two-part collaborative work is an homage to both the choreographer and Marcel Duchamp. In part one, Blue Studio: Five Segments, created by Cunningham and artist Charles Atlas, the video moves between personal and official records of time. The opening frames, with the credits “From New York / WNET Presents,” suggest that we are watching a public media production. We then hear a phone ring, and Merce Cunningham asks to speak to Jasper Johns. An empty electric blue studio morphs into a dimly lit city street as Merce and Jasper catch up. A superimposed Merce glides through the street, moving in place in the blue studio. The camera zooms in on his hand gestures, and an authoritative voiceover declares: “Merce Cunningham’s long career has been marked by daring experiment and consummate execution. At Lincoln Center in 1965, he was the first to combine dance with video, foreshadowing a new art form that has become known as video dance.” As Merce morphs from studio to street, so the experience of time transforms from that of a dancer’s memory to a page of dance history.

AS A PORTRAIT OF LATE-1980S VISUAL CULTURE, “FIN DE SIÈCLE II” DRAWS ITS MOST LIVELY SOURCE MATERIAL FROM THE MOVING BODY, HUMAN AND GRAPHIC.

In part two, Merce and Marcel, the question of who is presenting whom is further complicated by the presence of another subject: Duchamp. An inspiration to both Cunningham and Paik, Duchamp sets the stage for the changing nature of authorship over time. He invites an artist to put a new stamp on a found object—or footage or movement. Duchamp’s presence also ties in as the inspiration for Johns’s sets in Cunningham’s Walkaround Time (1968), film of which recurs throughout Merce by Merce by Paik.

Dance appears in many of Paik’s video works but is not often the primary subject. Even less often is it the element that draws attention or acclaim from observers and commentators. Perhaps that is to be expected; dance is commonly relegated to the margins of the larger cultural playing field. Yet some do champion Paik’s work with dance. David A. Ross, former director of the Whitney and a friend of Paik’s, writes: “The 1978 work, Merce by Merce by Paik, is probably one of Paik’s most underrated, but should be seen as one of his most direct and profound.” Underscoring the power of dance and video to throw light on time, he continues: “What quickly emerges is the notion that time is the subject of this work, time as experienced by the dancer in action, and the relative nature of time as the malleable component of video art.”3

Merce by Merce by Paik layers explicit philosophical prompts on the concept of time—in the form of Duchampian puns and rhetorical questions—with audiovisual time warps produced by the choreography and layered frames. In a motif of Blue Studio, Cunningham glides his feet as if figure skating yet stays centered on the screen: a video-art treadmill. The choreographer is superimposed on footage of a railway track streaming by. We hear a clip from what sounds like a post-talk Q&A. A woman’s voice asks:

Merce Cunningham mentioned occupying time. On the other hand, one often hears the expression “I’m going to kill some time.” It’s a silly question, but can one kill time?

The answer is both verbal and danced. Cunningham quips that it “seems to be the other way around.” Then, adding to the thought, he mentions “watching a lot of video” and “this thing that happens . . . ” His voice trails off; movement continues and takes over. A female dancer rendered in old black-and-white film, Cunningham dancer Ellen Cornfield, occupies the background with measured, elongated port de bras and forward penchées. In the foreground, Cunningham dances within a different aesthetic and rhythmic time, wearing a yellow jumpsuit and mirroring the staccato sounds of an electronic score with quick pivots, retirés, and small jumps. Who knows what it means to kill time, but Paik and Cunningham certainly annihilate any attachment one might have to a linear notion of time.

Past and present converge with the introduction to Duchamp in Merce and Marcel. The voiceover prompts:

Television obscures art in life and life in art, a theme favored by the late Marcel Duchamp, who believed a toilet bowl could be a work of art. Can we reverse time and bring back Marcel?

Dance theorist Mark Franko locates Merce and Marcel as the moment in which the notion of time emerges as the organizing principle of the work. Mortality is questioned. Interviews given by Duchamp and by Cunningham are interspliced, allowing the two artists from distinct eras to coexist. In a 1976 text, “Input-Time and Output-Time,” Paik wrote: “Once on video tape, you are not allowed to die . . . in a sense.”4 Paik emphasizes this temporal embalmment, this deployment of video to manipulate time in Merce by Merce by Paik, by playing sequences of footage in reverse and repeat—a “dance of time,” he is known to have termed it. Franko muses on this dancing of time in the work and its power of reincarnation: “While video adds a fourth dimension of time to painting, it adds to dance a different temporal dimension—that of the past, or replay.”5

DANCE AND VIDEO COMBINE TO LEAVE THE VIEWER WITH A PLAYFUL YET PROFOUND SENSE OF AN ENDLESS PAST AND A PERPETUAL PRESENT.

Viewers of Fin de Siècle II, however, see only an isolated clip of Merce by Merce by Paik—that is, if they arrive at the right moment or stay long enough. There is no voiceover to guide a theoretical investigation, yet Cunningham and his fellow dancing bodies on the installation’s screens bump up against, and break through, the contours of time. Curator Christiane Paul has spoken of the “different kinds of gestural expression” in the work’s videos of Cunningham, Bowie, and German band Kraftwerk.6She calls attention to the juxtaposition and visual parallel of the figural diagram and Cunningham, and the wireframes of the disembodied heads bopping to the robotic beat in the Kraftwerk music video. Another piece of footage recalls the treadmill effect in Merce by Merce by Paik, showing a nude woman moving in perpetual linear motion yet making no progress.

These individual time-based experiments flash and smash against one another in the collage of Fin de Siècle II as Paik choreographs moving bodies across screens with his intricately programmed sequence of videos. Dance and video combine to leave the viewer with a playful yet profound sense of an endless past and a perpetual present. Bowie sings, “I’ve been waiting so long,” and Kraftwerk chants, “Music non-stop.”

Reflection of Historical Time

Just as Fin de Siècle II cracks open the metaphysics of time à la Deleuze’s “crystals of time” in cinema, so too does the installation refract history’s periodization of time. Paik’s title was, in a sense, part of a renewed interest in the art and culture of the late nineteenth century—the language nods to France as the epicenter—that arose as the end of the twentieth century set in. The video sculpture takes the pulse of its time, situating the approaching turn of the century in relation to its historical precedent one hundred years before, and priming the viewer for the brink of the new century ahead.

In The Politics of the Very Worst, philosopher Paul Virilio connects the “transportation revolution of the nineteenth century and the virtual technologies of our own fin de siècle.”7 The central link, for Virilio, is speed. Paik seems to agree. Fin de Siècle II channels the speed of bodies in motion and 1980s mass communication technology to choreograph a high-velocity collage. Smaller television screens around the installation’s perimeter form a frame with twentieth-century iconography,8 evoking the transportation revolution through images of cars and planes and the communication revolution through meta-images of television and video cameras. This juxtaposition also draws a line between the fear of drab conformity associated with the Industrial Revolution and the fear of the surveillant, dystopian powers of the Communication Revolution. (Paik countered the latter notion most explicitly in his Good Morning Mr. Orwell, aired on New Year’s Day, 1984.)

TIME AND AGAIN WE SEE IN PAIK THE INTERSECTIONS OF LIVE PERFORMANCE, BROADCAST TELEVISION, SCULPTURAL INSTALLATION, AND RHYTHM, USING MEDIA NEW AND OLD.

The central cross-section panels of Fin de Siècle II present or allude to figures of the twentieth century: Bowie, Cunningham, Duchamp (the latter through images of a female nude in computerized motion, rather than descending a staircase). Contemplating the video wall, one could draw another parallel (and surely more) between the two fins de siècle. While the work puts forth an accumulation of mostly male auteurs, gender comes off as anything but definitive. Writer Tara Isabella Burton sees Bowie, gender bender par excellence of the twentieth century, as an inheritor of the dandyism of the nineteenth century, embodied by the likes of Oscar Wilde.9The clip in Fin de Siècle II displays a white-clad Bowie suavely trading partnering roles with Lecavalier; Bowie supports her barrel jump over his back and then stands still while she lifts him vertically below the hips.

By contrast, these trans-historical threads illuminate what is inarguably distinct about the work’s time, the late 1980s. As a portrait of late-1980s visual culture, Fin de Siècle II draws its most lively source material from the moving body, human and graphic. Dance can sometimes function as visualized music (though Cage and Cunningham would insist on the autonomy of each10 ), and visualized music was precisely what was on everyone’s television screens at the time, the lifeblood of MTV. Rather than shun mass culture as distinct from “high art,” Paik saw its genius and its resonance with his artistic concerns of time and accelerated mass communication across media. Paik’s spotlighting of TV programs and music videos in his work is distinct from the earlier Pop art movement, which sought to comment on the banality of mid-century material consumerism. Instead, Paik placed art and entertainment on the same plane, reflecting a sociological phenomenon of the late twentieth century: the cultural omnivore.11 Paik responded to and whetted the zeitgeist’s appetite for Bowie and Cunningham, for MTV and Philip Glass, served on the same channel, performing at the same time.

—

Paik channeled a hundred years of revolutionary art that came before him, yet, he was ahead of his time—global before the global trend of contemporary art.12 Christiane Paul sees in the choreography across screens in Fin de Siècle II an anticipation of today’s YouTube remix culture: “I think he always was a visionary with that. I’m actually not sure if Fin de Siècle, for him, wasn’t the future of the ‘electronic superhighway’ that he saw coming.” But as Martha Graham once said, “No artist is ahead of his time. He is his time; it’s just that others are behind the time.” To me, in Fin de Siècle II, Paik seems neither before his time, of his time, nor ahead of his time. Rather he was all these, at one time.

1Dick Higgins, “Intermedia,” The Something Else Newsletter 1, no. 1 (February 1966). Available online at http://www.primaryinformation.org/oldsite/SEP/Something-Else-Press_Newsletter_V1N1.pdf.

2William S. Smith, “Nam June Paik at Asia Society,” Art in America, February 27, 2015. Available online at

3David A. Ross, “Nam June Paik’s Videotapes,” in John G. Hanhardt, Nam June Paik (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1982), p. 108.

4Nam June Paik, “Input-Time and Output-Time,” in Video Art: An Anthology, ed. Beryl Korot and Ira Schneider (New York: Raindance Foundation, 1976), pp. 98–124.

5Mark Franko, “The Readymade as Movement: Cunningham, Duchamp, and Nam June Paik’s Two Merces,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 38 (Autumn 2000), pp. 211–19.

6Interview with the author, February 2019. Paul is adjunct curator of digital art at the Whitney and co-organizer, with Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, of Programmed.

7Paul Virilio, Politics of the Very Worst: An Interview with Philippe Petit, (New York: Semiotext(e), 1999), p. 13.

8Bonnie Marranca, “The Century Turning: International Events,” Performing Arts Journal 12, no. 2 (1990), pp. 66–74. Available online at muse.jhu.edu/article/654715.

9Tara Isabella Burton, “Bowie, Wilde, and the Fin de Siècle Dandies,” Jstor Daily,March 17, 2016. Available online at https://daily.jstor.org/bowie-fin-de-siecle-dandies/.

10See, for example, Merce Cunningham, “Space, Time, and Dance,” Trans/Formations 1, no. 3 (1952), pp. 150–51.

11Irmak Karademir Hazir, “Cultural Omnivorousness,” Oxford Bibliographies, 2015. Available online at http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756384/obo-9780199756384-0134.xml.

12In 1973, for example, Paik’s Global Groove engaged a network of cities around the world through a broadcast of a cross-cultural dance montage (in which Cunningham made an appearance).

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018–April 14, 2019

Artwork © Nam June Paik Estate; photos: Ron Amstutz, unless otherwise noted

No comments:

Post a Comment