More Obscene than De Sade

In his biweekly column, Pinakothek, Luc Sante excavates and examines miscellaneous visual strata of the past.

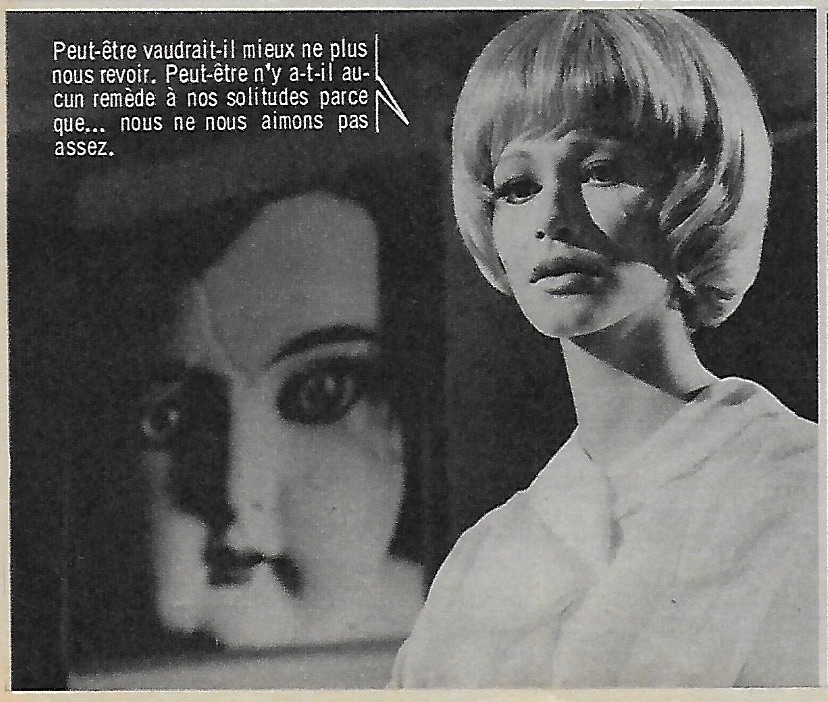

“MAYBE IT WOULD BE BETTER IF WE STOPPED SEEING ONE ANOTHER. MAYBE THERE IS NO REMEDY TO OUR SOLITUDE BECAUSE … WE DON’T LOVE EACH OTHER ENOUGH.”

Fotonovela, fumetti, roman-photo—the terms betray the fact that the form never got much traction in the Anglo-Saxon realm. There is no word for it in English, exactly. You could say “photo-comics,” but you’d risk being misunderstood. These narratives, often but not always romantic, are conveyed by means of photographs arrayed in panels on a page, with running text often in talk balloons. Their impact has been almost entirely restricted to countries that speak Spanish, Italian, or French; their readership is overwhelmingly female, at least in Europe. Their history formally begins in 1947 in Italy, in the magazine Grand Hotel, soon followed by its French sibling, Nous Deux; both magazines still exist. Fotonovelas flourished in the fifties and early sixties (into the eighties in Latin America), then began a slow decline that still refuses to yield to extinction.

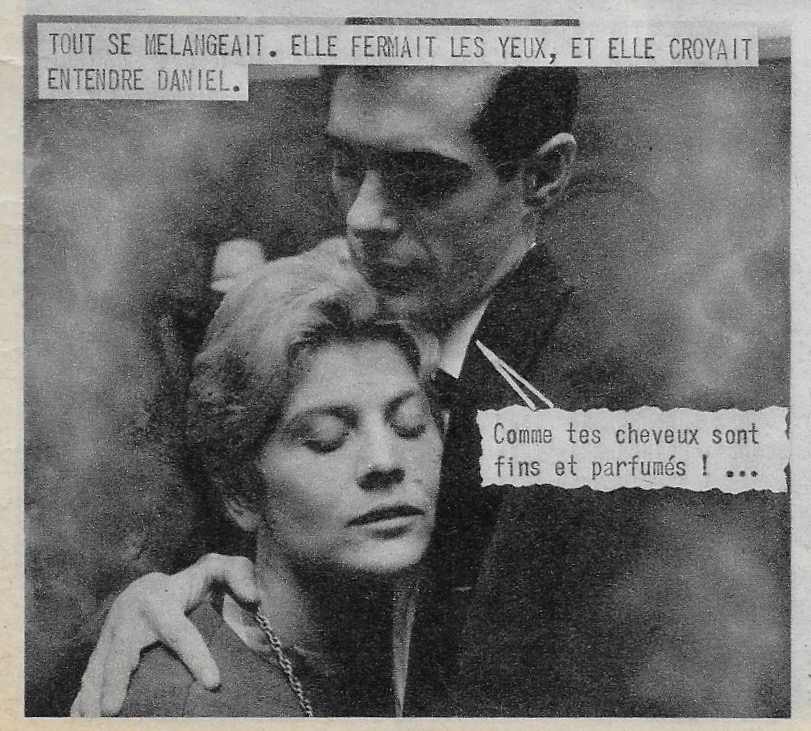

EVERYTHING WAS ALL MIXED UP. SHE CLOSED HER EYES AND THOUGHT SHE HEARD DANIEL. “YOUR HAIR IS SO FINE AND AROMATIC!”

The culprit of their near-demise, of course, was television, in combination with social anxiety. Fotonovelas were associated with the poor and unlettered (my mother aspirationally ignored their weekly appearance in Femme d’Aujourd’hui, to which she subscribed for almost fifty years), the naive and sheltered and perhaps delusional. Roland Barthes, having written that “love is obscene precisely in that it puts the sentimental in place of the sexual,” went on to call Nous Deux “more obscene than de Sade.” Some years earlier, in a less militant phase, he noted of the fotonovelas that “their stupidity touches me” and ranked them with other “pictographic” forms, such as stained-glass windows and Carpaccio’s Legend of St. Ursula. There are even more specific antecedents, although no record of actual influence: Nadar’s famous conversation with the centenarian chemist Michel Chevreul was published as sequential captioned photographs in Le Journal Illustré in 1886, and La Folle d’Itteville, the collaborative photo-novel by Germaine Krull and Georges Simenon, was published in 1931.

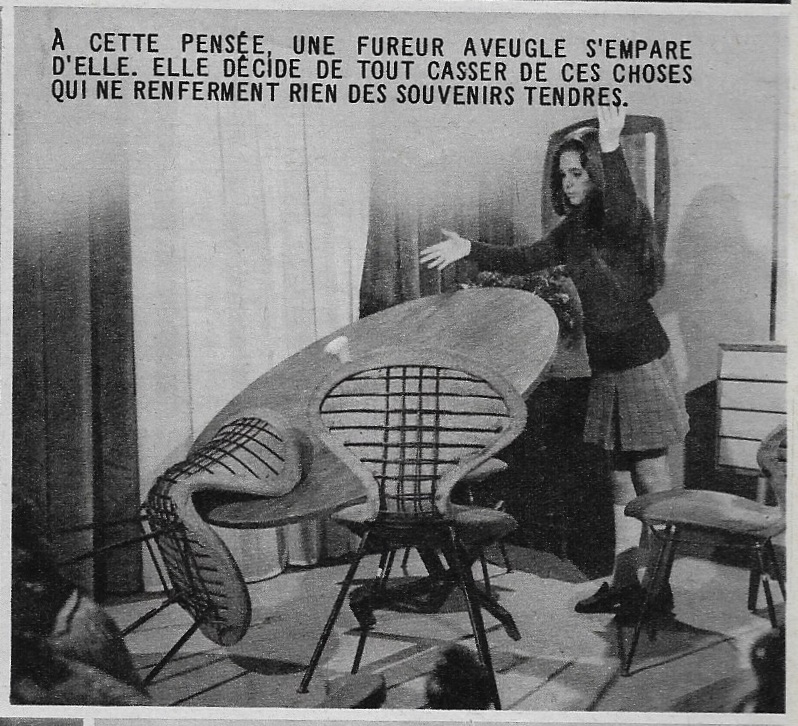

AT THIS THOUGHT A BLIND FURY TAKES HER OVER. SHE DECIDES TO SMASH EVERYTHING THAT DOESN’T ENCLOSE TENDER MEMORIES.

It comes as no surprise to learn that the immediate ancestor of the form was an Italian magazine series that adapted American films by using ordered stills and minimal text to convey their plots. The fotonovela is essentially a low-budget movie on paper, relying heavily on certain cinematographic conventions: the two-shot, the three-quarter shot, the close-up. Or it could be simply defined as a paper-based soap opera, since televised soap operas don’t waste much time on establishing shots, either. The forms also share romance-centered story lines and a traditionally female audience. There have been exceptions, such as the long-running Italian title Killing (Satanik in France), which ditched romance for sadistic violence, although it observed the same intimate scale; unlike most implacable, masked super-criminals, Killing preferred to murder with his hands. Other genres, including many low-budget film staples (the Western, the monster movie, the heist picture), are out of the question owing to their practical demands. On the other hand, the enclosed nature of the form means that you can set a story in the United States, say, by simply ensuring a few sartorial details, such as police uniforms.

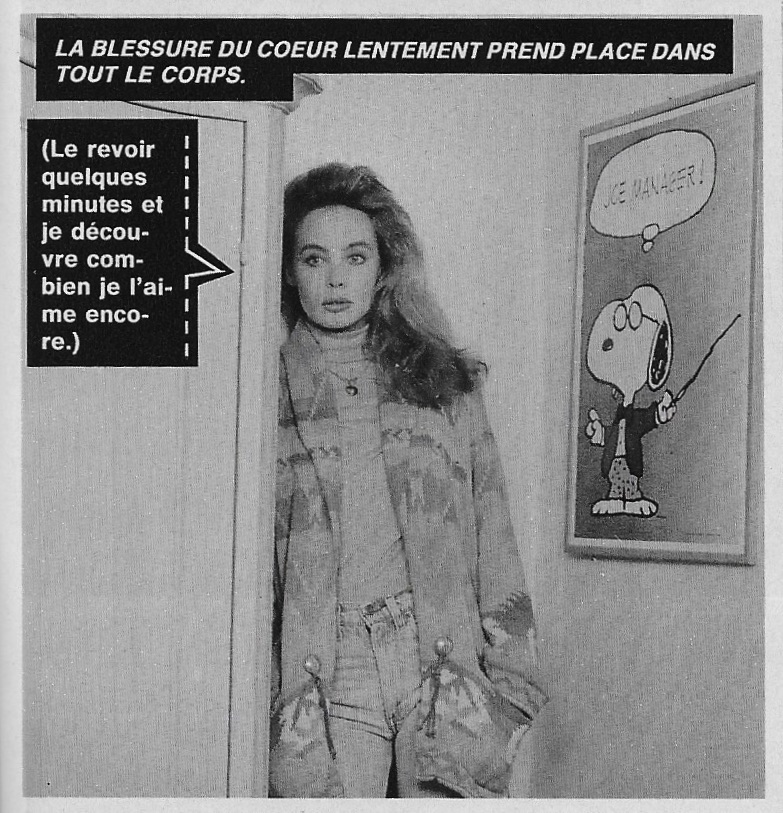

THE WOUND TO THE HEART SLOWLY SETTLES THROUGH THE BODY. “(I SEE HIM AGAIN FOR A FEW MINUTES AND REALIZE HOW MUCH I STILL LOVE HIM.)”

The European sartorial details, for their part, can intermittently put you in mind of French new wave movies, which were similarly low-budget and intimate. The visual difference between them has mostly to do with lighting; the fotonovela defaults to the soap opera’s full-coverage model, which has the intent and effect of eliminating any possible ambiguity. Its settings are ruthlessly bon chic, bon genre (but then you could say that about almost anything by Éric Rohmer); its casting choices tend toward archetypes of beauty, waywardness, or authority while avoiding distinctive appearances (but then, Sophia Loren and Claudia Cardinale both made their professional debuts in fotonovelas). Every frame is simply composed and centered; nothing is happening at the edges. The form differs most radically from cinema in its treatment of time, which in the fotonovela is entirely determined by the individual consumer. You can linger between frames if you wish—and you can also run the story backward or interleave it with another story—but the makers cannot introduce a long take or a jump cut or a music cue.

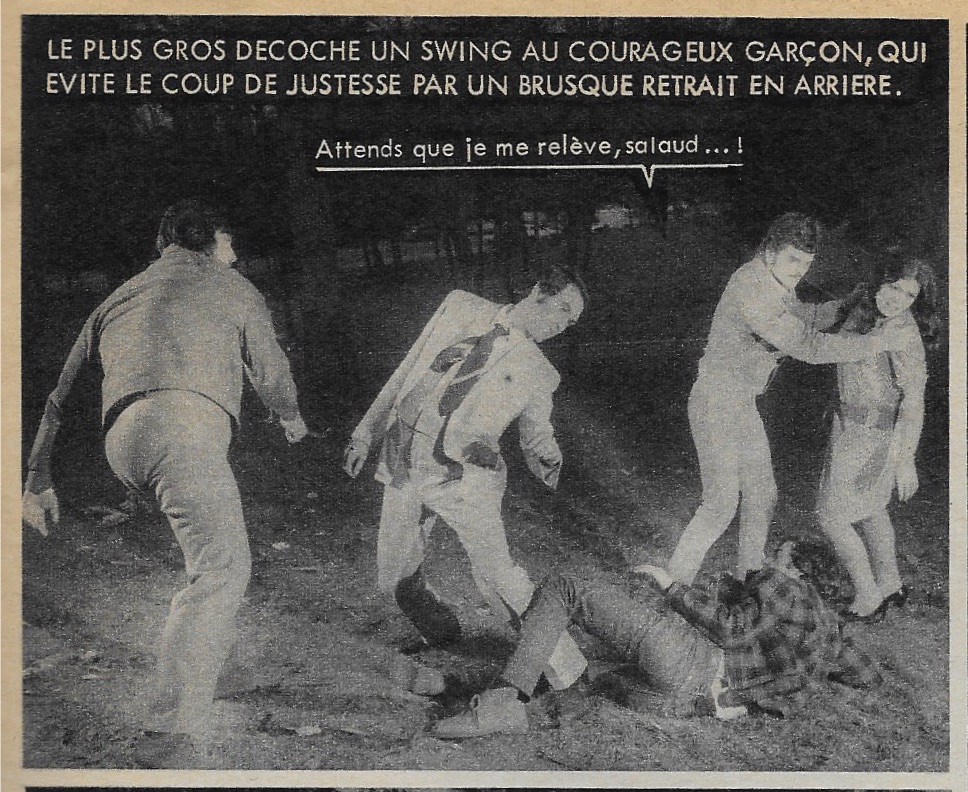

THE BIGGEST GUY SWINGS AT THE BRAVE BOY, WHO NARROWLY AVOIDS IT BY SUDDENLY STEPPING BACK. “WAIT TIL I GET UP, YOU BASTARD!”

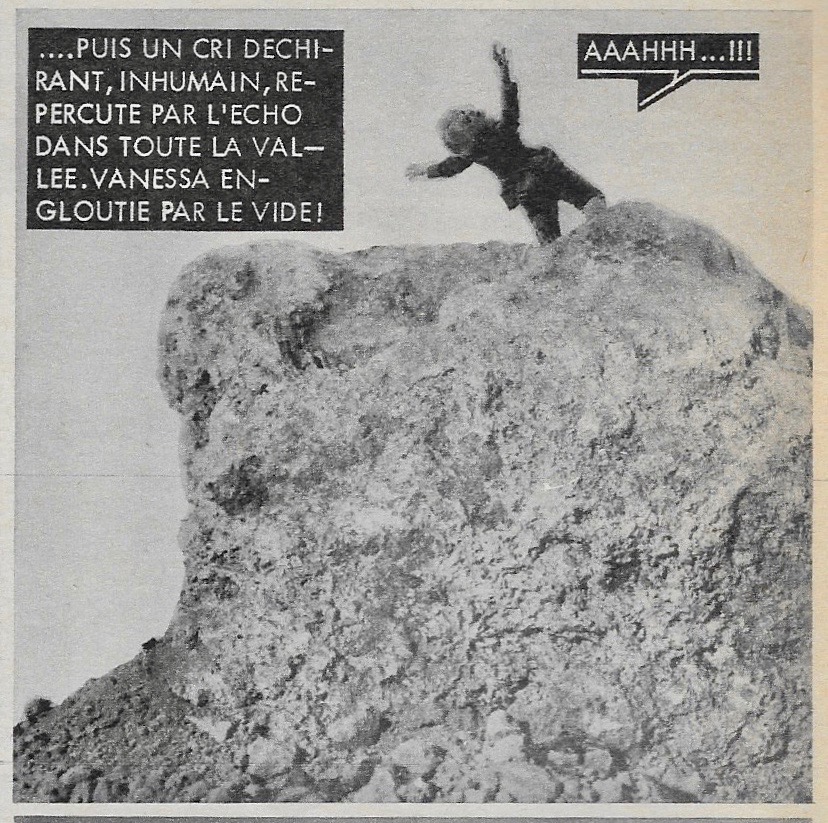

The form is simple and utilitarian, geared in every detail to meet common understanding. It is a screen for the reader to project upon while ostensibly immersed in the travails of fictional characters. It traffics in emotional hardware—longing, doubt, regret, passion, envy, betrayal—chiefly through verbal expression and mostly without dramatization. Plot points occur principally in the dialogue. Action, when it happens, is staged neoclassically; fights are choreographed and frozen, as on a Hellenic amphora or in a painting by Poussin. There is rarely any physical damage, and the actors are never mussed. Even when terrible things occur, the effects are muted. Fotonovelas can often seem like extended modeling sessions; the actors seldom strike poses that do not display their clothing to its advantage. It is as if the figures in a department-store catalog enacted a semblance of life, imagining what it must be like to feel, but held back by the immobility of their outfits. In their way, fotonovelas are a guide to comportment, promoting restraint and self-possession, directed at a working-class public that owns little but its emotions.

Luc Sante’s books include Low Life, Evidence, Kill All Your Darlings, and The Other Paris.

No comments:

Post a Comment