Pandemonia, New York Taxi. Photo by Simon Cave. Courtesy of Laurence King Publishing.

’s 2011 photograph Meeting is meant to make you uneasy. In a gentle morning light, the artist substitutes women subjects with frightening, human-like sex dolls, throwing a perverse reality into focus.

Through images like this one, which is part of the artist’s 2011 “Love Dolls” series, Simmons asks us to confront the extent to which women are stripped of their humanity or pictured as objects to be played with. “I don’t try to remove the dolls from their sexual origin,” Simmons explains. “I really use them as subjects in a story I’ve been telling for a long time—a woman’s interior. How does a woman become a character, and what does that character mean?”

This tension is under the lens in Grace Banks’s debut book, Play With Me: Dolls, Women and Art, set to release in October 2017 through Laurence King Publishing. The striking artworks featured—more than 60 in total—are at once jarring and familiar. Some recall the use of porcelain dolls in horror movies: objects of pristine innocence that, when placed in a dark context, are suddenly menacing.

The ways that dolls take on new meaning when thrust into different scenarios are explored at length in Play With Me, by way of profiling 43 different artists, both male and female, who use dolls as a means to study the role of female forms in contemporary art.

Elena Dorfman, CJ5 from Still Lovers Series, 2001. © Elena Dorfman. Courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery.

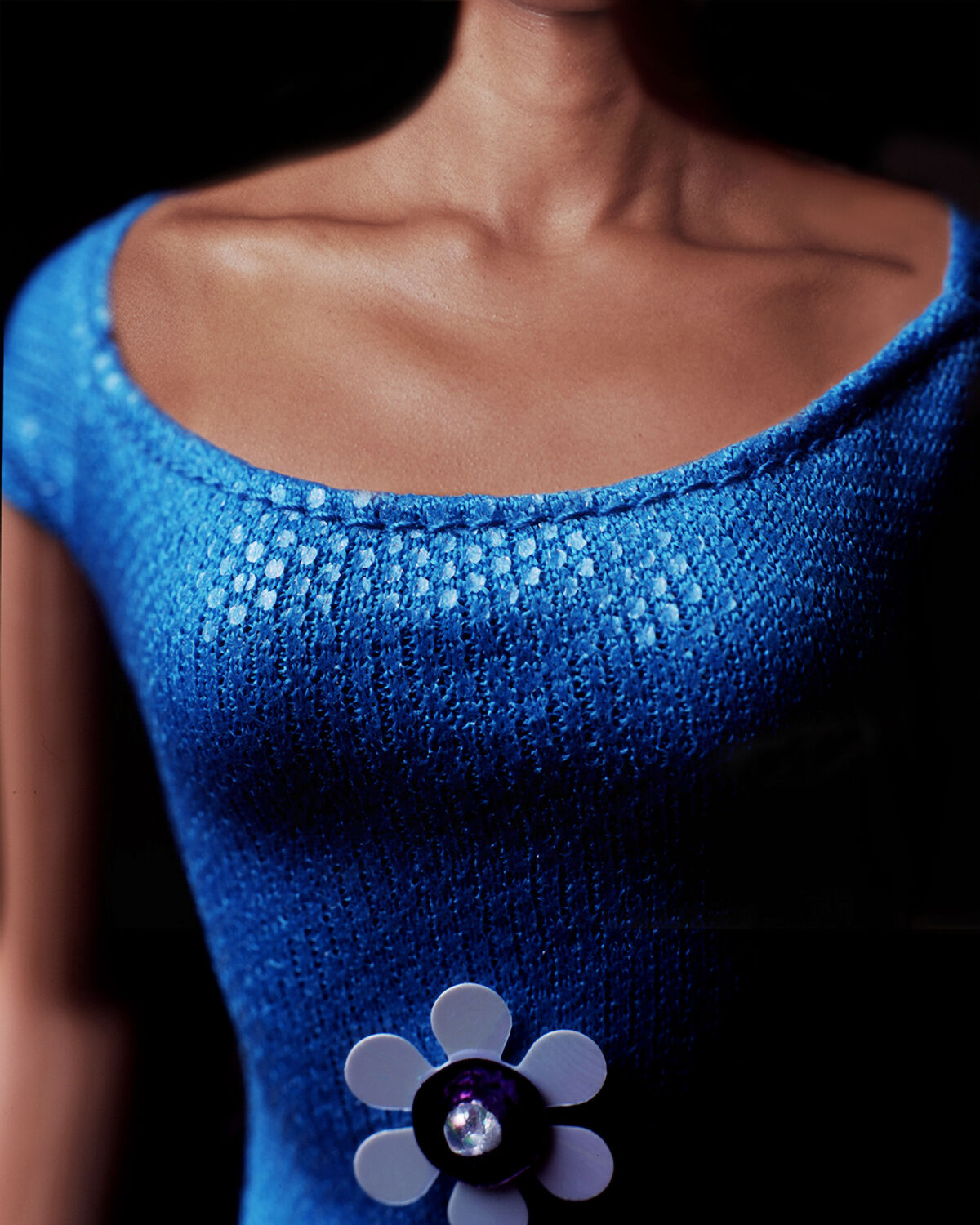

Sheila Pree Bright, Plastic Bodies Series, 2014. © 2017. Courtesy of Sheila Pree Bright.

“A doll is the ultimate objectification of a woman’s body,” Banks explains. “It’s a mass-produced archetype of a woman.” The artists featured in the book, she continues, have employed dolls for this reason: as symbols of objectification through which to develop new, contemporary visions of the female nude in art.

Banks traces this narrative back to 17,000 B.C., when nude women were first pictured in cave paintings. Broadening our definition of what a “doll” can be, she argues that the term can be used to describe any depiction of a female form that is devoid of humanness, or portrayed solely as the physical shell of a person. This timeline moves through the first female figurines and nude portraits of Grecian goddesses, to more contemporary work, such as

’s portrayals of female genitalia as flowers and

’sCut Piece (1964), a performance where viewers cut the artist’s clothing from her body, leaving her naked.

The crux of the book, however, focuses on art created in the past 15 years. Banks has dedicated each of four chapters to the various ways that dolls can be seen in contemporary visual culture: “Blow Up” covers sex dolls and the ways that brands commodify women’s bodies; “Muse” looks at plastic and silicone dolls and the toys that children play with; “Female Gaze” dives into the evolution of gender through dolls; and “Cyborg” examines the roles women’s bodies play in designing for the future. “With the tools once used to objectify them,” Banks writes, “these artists transform women’s bodies into a self-governed pièce de résistance.”

Stacy Leigh, Average Americans that Happen to be Sex Dolls, series 2014. Courtesy of Stacy Leigh.

Take, for example, the mannequin sculptures of German artist

, featured in the “Blow Up” chapter. For these works, Genzken sourced ubiquitous shop mannequins and dressed them in haphazard outfits to consider the social issues that women face. Banks refers to these sculptures as bodies shrouded in “emblems of broken stories,” nodding to their dependence on the viewer to decipher their meaning.

Part of the “Muse” chapter,

challenges the Barbie doll’s Western beauty standards with her 2014 series “Plastic Bodies.” According to Banks, Bright was inspired by the story of the “Hottentot Venus,” the South African woman who was brought to the U.S. on a slave ship and exhibited in a traveling “freak show,” forced to be a spectacle of foreign womanhood. For “Plastic Bodies,” Bright took photographs of women from Baltimore and enmeshed their bodies with Barbie dolls, which Americans are so accustomed to seeing. “Playing with a Barbie doll is, in my view, an aggressive confrontation with something which is just not a reality at all,” Bright says. “But by the very nature of creating work, I’m trying to introduce a new dialogue of how women might be portrayed in culture.”

Martine Gutierrez, Real Dolls Series, 2013. © Martine Gutierrez. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE, New York.

The featured works not only attempt to reconcile the past, but also look to our future. Those in the “Female Gaze” chapter consider the ways that female artists are defining how their bodies can be used moving forward in art. Artist

, who now identifies as a woman, “grew up collecting dolls, from Barbies as a child, to full-sized mannequins as an adult,” Banks writes. Gutierrez’s works bring us into progressive conversations happening around gender, identity, and sexual independence.

Gutierrez’s relationship to dolls appears traditional; she uses dolls as way to escape into a different world, just as children do. But in this world, gender is not an object, and violence towards gender ambiguity is not a concern. “The reality of the real world and the way I am perceived, fraught with bigotry, violence, and categorization, constantly upsets me,” Gutierrez explains. “I need to escape into this fantasy to re-imagine my own existence in a world where identity is fluid.”

Mai-Thu Perret, The Crystal Frontier, 1999-Present. Courtesy of Mai-Thu Perret.

Mai-Thu Perret, The Crystal Frontier, 1999-Present. Courtesy of Mai-Thu Perret.

The future is also of primary concern in the “Cyborg” chapter, where

is represented through works in which she has been reconciling her feelings about robot and cyborg technology for almost two decades. Her series, “The Crystal Frontier” (1999–2016), was originally inspired by an all-female, secular Kurdish military group in Rojava, Syria, and the physical strength of its women. “The Crystal Frontier” reimagines this storyline as a feminist community living in the New Mexican desert who are immortal.

“So much of women’s work depicting the female nude has been totally ignored by male art historians, and I wanted to look at these artists taking back the right to create the female nude on their own terms,” Banks explains. “I really liked the fact that some of the art in this book is unappealing, and not at all pretty. And I wanted to celebrate that. A lot of the artists I love just don't make work that’s easy to commodify, sell, exhibit in a gallery.”

Annie Armstrong

No comments:

Post a Comment