Art Market

The Rapid Rise of Millenial Collectors Will Change How Art Is Bought and Sold

Photo by Fuse, via Getty Images.

Groucho Marx once said that he wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would accept him as a member. I feel a similar skepticism about being part of a club I never asked to join. But my 1983 birth makes me a reluctant member of what demographers and marketers now call “millennials.” Like every generation, our predecessors say we’re spoiled and self-absorbed—Time magazine called us the “Me Me Me Generation.” History may one day overlook our supposed heroic self-regard and need for safe spaces, but for now the cliché of being over-parented, over-schooled, and over-protected isn’t completely off base.

The millennial mindset

We never had a summer of ’67, where we tuned in and dropped out, nor a May of ’68 or a March of ’89, where we seriously challenged societal order. Instead, we were weaned on self-esteem culture and entered adulthood amidst the collapsing scenery of the Great Recession. As economic late bloomers, wedelayed home-ownership, marriage, and children. We moved to cities, and spent our first decade’s harvest on experiences: travel, careerist-festivals (SXSW, Art Basel, TEDx), second-wave artisanal coffee, but not stuff (and notgolf either, for some reason). We traded boomer materialism for a new kind of lifestyle consumerism. On the art scene, we socialized, gossiped, and Instagrammed, but never actually bought many pictures. Until now. Anew survey of high-net-worth collectors by U.S. Trust reveals that our latency period is finally ending. Millennials are settling down, finding our financial footing, and beginning to collect.

Who we are

Courtesy of U.S. Trust.

Expanding from a small base, we’re suddenly the fastest-growing segment of collectors (though we still represent only a tiny sliver of sales). In my observation, we fall into two camps: wealth inheritors and a burgeoning group of rising private equity, real estate, and hedge fund professionals (the young tech elite still don’t collect).

As the degree-inflation generation, we’re far more likely to have received financial gifts or loans toward our success. We’re curious and ambitious, but not all that rebellious or revolutionary. We’re more likely to obey authority, and we basically operate within the system. Ours is a cautious careerism geared towards our self-actualization. Our conformity annoys boomers like David Brooks of the New York Times, who calls us “morally inarticulate” and unconcerned with “virtue.” But he may have a point. The great ideological struggles of the 20th century were less immediate to us. We grew up in a comfy post-Cold War liberal consensus and focused on our feelings. Sure, we debate tax rates and social policy, but we’ve basically accepted our commercial republic. Unsurprisingly, then, we collect like capitalists.

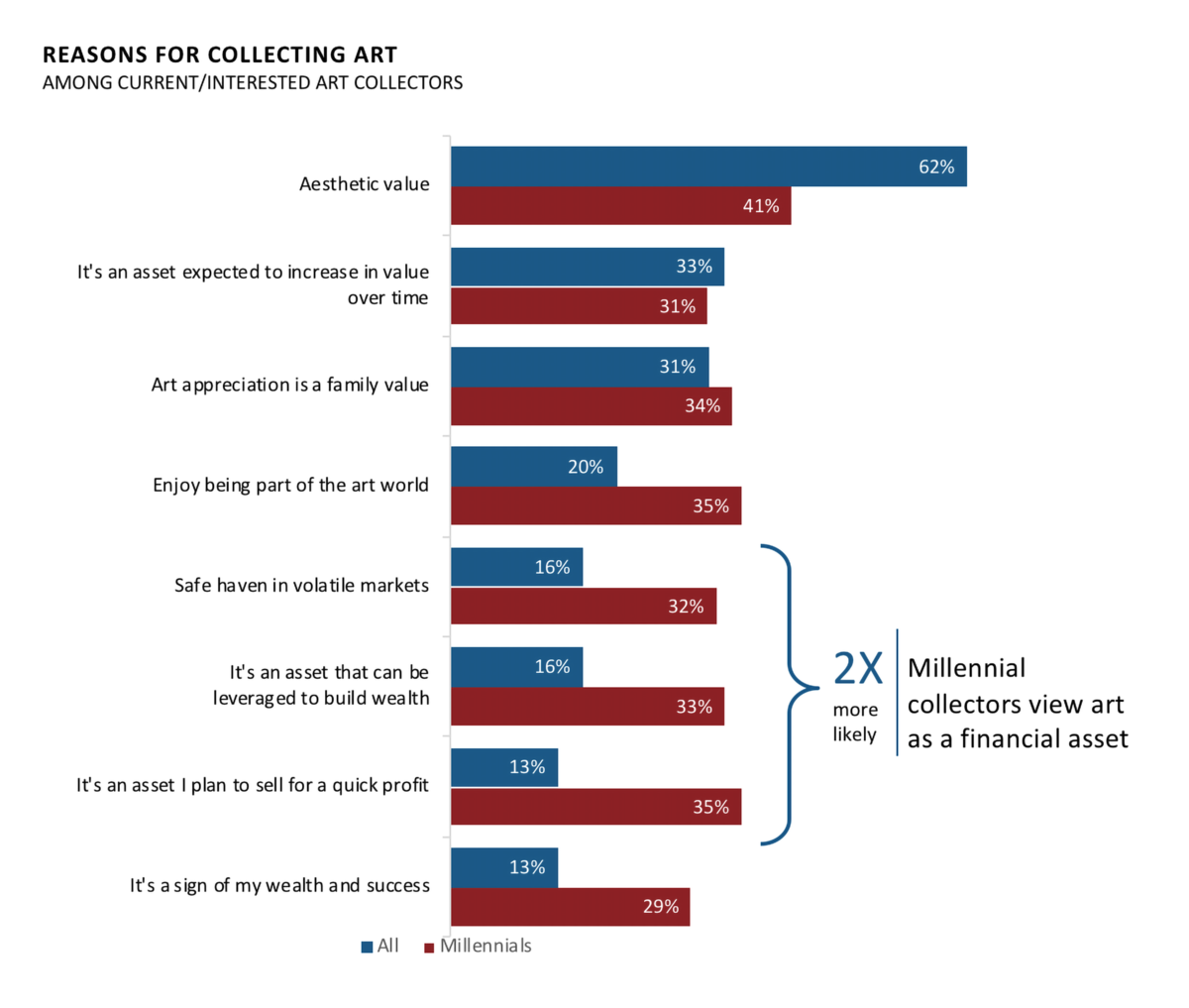

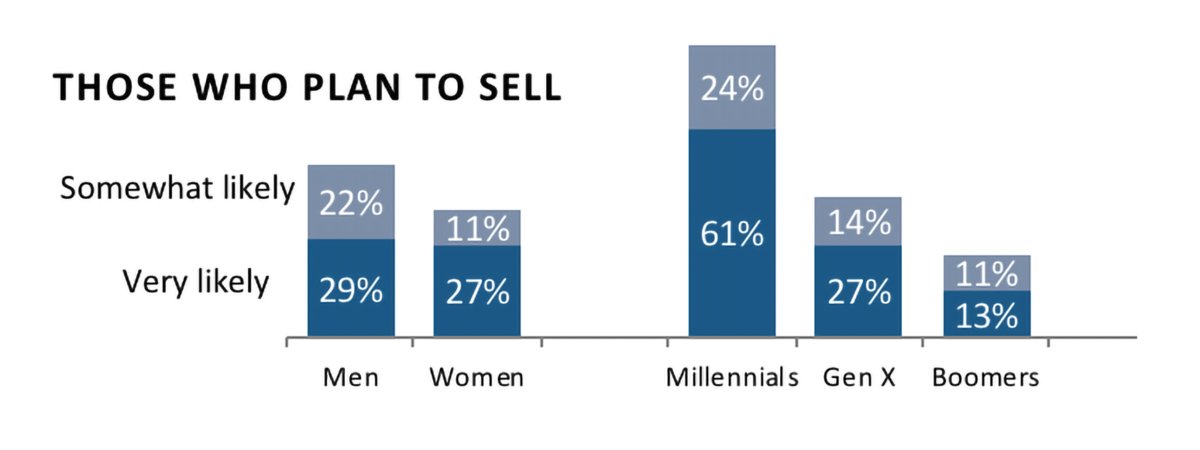

How we collect

Courtesy of U.S. Trust

What does that mean? We’re more transactional and more attuned to how our art behaves as a capital asset. We’re over three times more likely than boomers to sell works we’ve collected (85% to 24%). A misconception exists that we collect for investment. In fact, we have no choice but to be enterprising if we want to own the influential art of our time.

“I collect because it enriches my life, but it’s certainly become more difficult to on-ramp into collecting,” says Nilani Trent, a 30-something art advisor and early collector of artists like

,

, and

. “It now requires $50,000 to acquire even the youngest, most untested artists.” Collecting serious art for aesthetic pleasure even for the super-rich has become unreachable. Our venture mindset is a response to the market’s structure.

,

, and

. “It now requires $50,000 to acquire even the youngest, most untested artists.” Collecting serious art for aesthetic pleasure even for the super-rich has become unreachable. Our venture mindset is a response to the market’s structure.

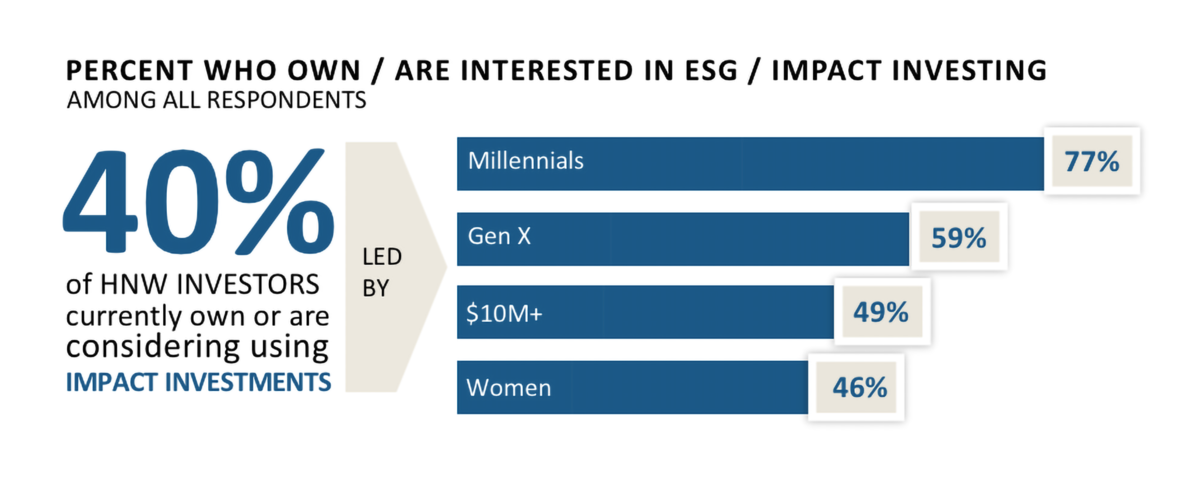

Making a difference?

Courtesy of U.S. Trust.

But it’s not all about the money for us. We were told that we could be anyone we wanted to be. So we now invest and collect with a sense of idealism—boomer rebellion has given way to “making a difference.” We’re far more likely to care about the social impact of our investments and three times more likely than boomers to consider our art collecting a part of our philanthropic aspirations (89% to 27%).

Sarah Arison exemplifies the new, more socially conscious collector. As chair of the board of trustees of YoungArts and a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum, she’s incorporated her collecting into her philanthropy (rather than the other way around). “I collect a lot of works from young artists who go through the National YoungArts Foundation program,” she notes. “It can create an impact for them in furthering their career.” We’re seeing more collectors finding ways to fuse their collecting with meaning.

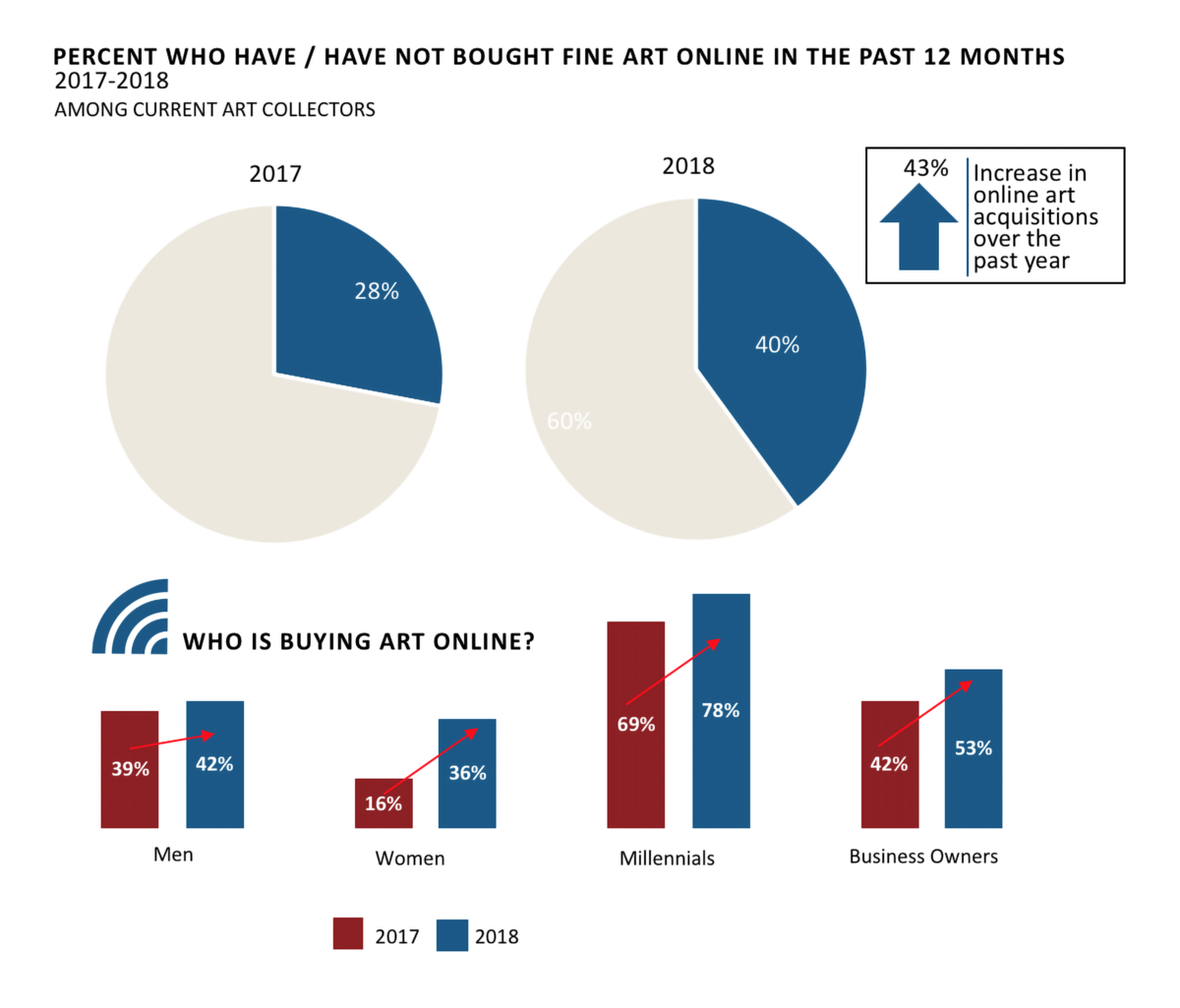

Technology and transparency

Courtesy of U.S. Trust.

A lot has been made about our digital nativism—our isolated, over-exposed, decreasingly religious existence, which has made us more susceptible to self-help guruism, overheated TED talks, and utopian rhetoric about AI this and blockchain that. But although we speak in code—V, LMK, JK, TBH—and increasingly buy art online, technology will only moderately change how we collect.

We’ll co-opt art and technology to enhance our personal brands—not so much in our real lives, but in our digital avatar lives on social media. Trent says that Instagram “has been the real game-changer for the art world.” It’s the perfect mix of visual and social. She notes that “for the first time, a completely open awareness exists about who owns and who collects what.” This hyper-connected transparency will expand the art market, but may also move our collecting towards fashion, with its insta-trends, branding, and channel buzz (there must be at least one hedge fund manager not looking to acquire a

right now).

right now).

Age of identity

There is one mega-trend that my generation may end. If 19th-century art was about beauty and the 20th about concepts, the 21st century has been about identity. Earlier this year, I attended an acquisitions committee meeting at a West Coast museum. Each curator had five minutes to make a Shark Tank-style pitch to trustees on why endowment funds should be spent on their chosen work. As the session wore on, I was struck by how little anyone said about the actual art. Nothing on composition, form, or even historical context. Every pitch focused on the artist’s biography: race, sexual identify, feminist credentials, overcoming hardships.

It’s part of a broader (and overdue) reexamination of minority and female artists by boomer curators and collectors. But I think the moment is short-lived. You see, our cultural third rail is inclusion—wokeness, leaning in, white rappers, black golfers, the ever-expanding LGBTQ spectrum. We think

is a damn good artist, not a damn good black artist. And as we become a dominant collecting force, identity will become less central, and art will again have to stand on its own aesthetic merit.

is a damn good artist, not a damn good black artist. And as we become a dominant collecting force, identity will become less central, and art will again have to stand on its own aesthetic merit.

What this means for the art market

Collectors aren’t sellers is no longer a thing. It’s my generation that Equinox Fitness is targeting with its “Commit to Something” tagline. Galleries will need to adapt to our trading mindset. Dealers will need to become less coy around pricing and more accepting that we may want to—gasp—sell. We lack an exaggerated regard for social standing (unless it’s a celebrity), so the art world, especially gallery staff, will need to become less affected. We value convenience—so you’ll get to work on that virtual reality option so we can attend your London opening from our iPhones. Finally, we’re curious (and over-educated), remember. We want scholarship and gravity from our arts institutions, less populism.

Evan Beard is the National Art Services Executive at U.S. Trust, Bank of America Private Wealth Management.

This content represents thoughts of the author and does not necessarily represent the position of Bank of America or U.S. Trust. U.S. Trust operates through Bank of America, N.A. and other subsidiaries of Bank of America Corporation. Bank of America, N.A., Member FDIC. © 2018 Bank of America Corporation. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment