Ellen von Unwerth: Ladyland in a Man’s World

Her photographs may scream female sexual liberation, but Ellen von Unwerth isn’t for everyone. Emily Steertakes a trip to Ladyland—the German photographer’s latest show in London.

“We can’t film in that direction; we’ll get the nipples in shot.” I’m jostling my way around a sizeable TV crew who are squeezed into Ellen von Unwerth’s Ladyland, shouting instructions to one another and hauling large pieces of equipment through the claustrophobic basement of Mayfair’s Opera Gallery. The sight of this burly crew feels at odds with the suggested female utopia of Ladyland. It is also a very obvious reminder of the huge proportion of men who tend to work behind the camera. This is where Von Unwerth comes into the picture. At a discussion I went to recently about the female gaze she was one of the only female commercial photographers who anyone on the panel could name (alongside Annie Leibovitz, of course), which puts her in a position rather loaded with expectations to beat the boys at their own game. Although Von Unwerth is a woman primarily photographing women, her work evades easy categorization alongside the growing number of female photographers who explore the female gaze, as it plays into as many cliches as it subverts. As someone whose bookshelves were loaded with weighty tomes on Sam Haskins and Roy Stuart as a teenager, I am hugely drawn to her work, but I feel conflicted—I like it (a lot), but I’m not sure if I should.

Von Unwerth began her career in the fashion industry as a model. “I think that because I know what it feels like to be in front of the camera, I can be more sympathetic to my subjects,” she writes to me. “Being in front of the lens, you are very vulnerable. It’s not a nice feeling, and I don’t miss it. But it’s very helpful to know exactly what it’s like. When I was a model I hated when I wasn’t allowed to move, so I love movement and I encourage my subjects to play around, to move and to be silly. In terms of the way I portray women, I want to immortalize a woman’s personality, enhanced and exposed. Often, women appear self-assured, having a lot of fun in my pictures, and that is because it is what is actually happening during the shoot.”

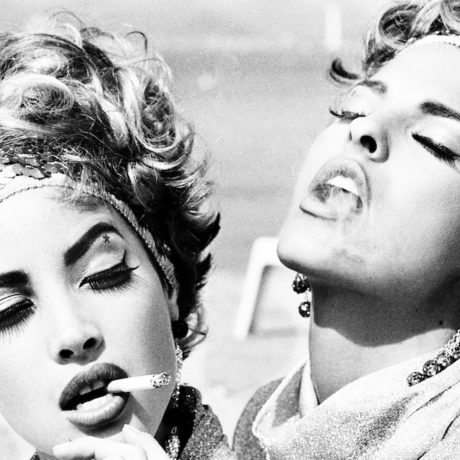

Her female subjects—depicted as sexually liberated and playful—cackle and glare into the camera with piercing, snake-like eyes, celebratory and overbearing. There is a sense of fun that pervades, present in the tongue-in-cheek Coca-Cola cans that take the place of hair rollers in one photograph of Naomi Campbell, and in the Cheshire-Cat-like toothy grins that shape the heavily-lipsticked mouths of her models. It’s confronting to see a female photographer work in this zone. Leibovitz (who famously headed up the Pirelli Calendar’s 2016 reboot with a more sedate take on female empowerment), for example, eschews the lineage of Helmut Newton to show her subjects in a classically dignified manner, which can often veer into drabness.

Von Unwerth focuses almost entirely on female subjects, and when men do appear in shot, they tend to be shown with women who they already know intimately—David Bowie is photographed with close friend Kate Moss in one massive print in the doorway to Ladyland, and Vincent Cassel with his then-wife Monica Bellucci—or they take an apparently submissive role.

There’s an element of the ridiculous to her work, a cartoonishness that propels the images into a realm beyond the dynamic of the watcher and the watched, as her subjects appear to inhabit lively characters and imagined versions of the world in a manner akin to the pomp and preposterousness of David LaChapelle. “I take pictures all the time and I am always thinking about new narratives to feed my work,” Von Unwerth writes. “I am lucky that I get inspired by many various sources in life: art, music, cinema and fashion. I always organize my shoots like movies. Initially I have a narrative in mind, it can often be a mixture of inspirations and I work from that. Which means I write a little story, then cast the people accordingly, choose the location and the crew, and always work with music on set that fits the story.”

Von Unwerth walks a fine line, purposefully screwing with the image historically created by male photographers for female models to act out, but also abiding by many of the rules that come with it, not least in her choice of models, which tends to fit with the accepted beauty standards of our time. Seeing the works en masse, I wonder how I might feel about them if I knew the photographer was male—and have to consider the extent to which the gender of the photographer should influence the way we feel about the images they’re putting out into the world. Is Ladyland accessible to all women, or just the chosen few?

No comments:

Post a Comment