Art Market

Why the Art Market’s Simplest Form of Transparency Fell out of Favor

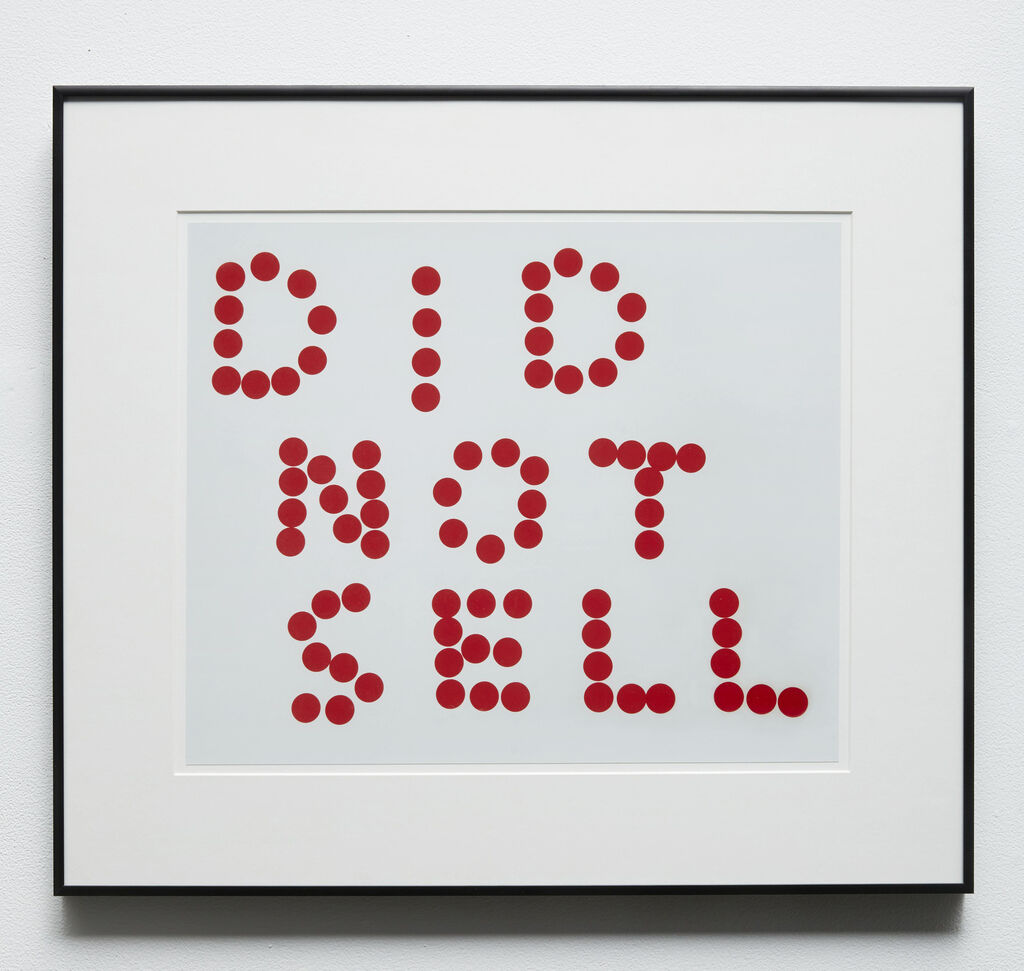

John Waters, Congratulations, 2014. © John Waters. Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers.

It’s a quarter-inch, circular red sticker, available in packs of 450 for under four dollars. But this tiny dot answers the question that powers the art market: “Can I buy that?”

Back in the 1970s, red dots were a common sight, located on the walls of galleries or art fair booths to indicate that a work was already sold. But today, especially at the high end of the art market, they’re increasingly scarce.

The slow disappearance of red dots at the top end of the market, combined with their steady use at fairs that offer lower-priced works, illustrate how an increasingly polarized market relies on different sales tactics. At the high end, where cultivating relationships with collectors is key, the lack of visible information about availability forces collectors to approach someone and inquire. At the low end of the market, their continued use signals to novice collectors that it’s okay to take the plunge.

At fairs, “we leave [a sold work] on the wall without a red dot to be able to get into a conversation with clients, as we have a similar work that we could offer and pique their interest,” said Heike Grossmann, a director at Galerie Thomas in Munich. Galleries often have more, similar, or perhaps even more impressive works in a back room, and the first step is engaging a prospective buyer in conversation.

By contrast, red dots can be helpful in closing sales at fairs catering to new art collectors, who are browsing works at lower price points. They may be looking to buy, but aren’t necessarily out for a particular kind of art or armed with a wealth of art knowledge, in contrast to the seasoned collectors who attend international mega-fairs like Art Basel.

“Over the past few years, red dots have been used consistently at our fairs,” says Cristina Salmastrelli, director of Affordable Art Fair in New York. “For our visitors, we see that the red dots create a sense of urgency in them to fall in love with a piece of original artwork and take it home that same day.”

As the fair progresses and dots can be seen across the venue, Salmastrelli notes, they send important messages to novice collectors. Consumers are influenced by trends, and red dots signal which artists or styles are in demand.

Affordable Art Fair, New York City 2017. Photo by Reed Photographic. Courtesy of Affordable Art Fair.

Though the origins of the practice are uncertain, some have traced it back to the mid-1800s, when red stars began to be placed next to sold artworks at the annual summer exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. Despite this, some allege that it’s an American tradition. Eventually, the star became a circle, and later, iterations emerged.

“I saw the red dots when I began to visit art galleries in the mid-’70s,” said Patrice Cotensin, a director at Galerie Lelong in Paris. “It seemed to be a ‘rule,’ with also the green dot (or a half of red one) for a work ‘on hold.’” Multiple red dots can be used in the case of prints and other works that have several editions.

In the past decade, use of red dots has widely been considered in poor taste, particularly among Americans. In her bestselling book from 2008, Seven Days in the Art World, Sarah Thornton writes of Art Basel in Switzerland, “There are no prices or red dots on the wall. Such an overt gesture at commerce is considered tacky.”

The rejection of an “overt gesture of commerce” comes, ironically, as the prices for art have floated into the stratosphere. This is another reason that contributes to the disappearance of the red dot: As prices have risen, the level of discretion demanded by buyers has climbed in tandem. Another explanation traces their demise to the post-financial crisis period, when sales were volatile and few dealers wanted to broadcast their travails.

“The red dot display system does lay oneself open when sales have not been made, which may be the reason some galleries have dropped the use of red dots in recent years, during a more turbulent market,” said Emma Ward, managing director of Dickinson in London.

But among European dealers, red dots are used more frequently. “I know that many American art dealers consider the ‘red dot’ as highly vulgar,” Cotensin said. At Galerie Lelong in Paris, red dots are used in gallery exhibitions. “In Europe we don’t have this feeling, except for European art dealers who want to appear as ‘American-style’ business people.” Unsurprisingly, Lelong’s New York gallery (located among fellow leading galleries in Chelsea) does not use red dots.

Affordable Art Fair, New York City 2017. Photo by Reed Photographic. Courtesy of Affordable Art Fair.

Advocates for the continued use of red dots say they bring much-needed transparency to a market where much is still shrouded in mystery. The right kind of buyer, Ward explained, will be attracted to that kind of openness.

“Genuine buyers respond very positively to seeing a price openly printed on the label of an artwork, giving security that different prices are not quoted, or fees to intermediaries are not added on top,” Ward noted. “We also use dots to indicate when a work is reserved and if a second party is interested in a reserved or already sold piece, we keep that party updated or try to find another similar work that fits the request.”

Another factor in the diverging attitudes towards dots stems from the kind of art a gallery sells. In the case of galleries that specialize in Old Masters or Modern and Impressionist works—the bread and butter for art galleries that show at TEFAF, for example—there’s much greater scarcity, so a red dot is more decisive; it’s not likely that another, similar rare painting is tucked away in the back room.

On the other hand, for galleries working with post-war and contemporary artists, there is likely much greater supply available. If a collector is interested in a sold work at a fair, for example, the gallery director can guide them into the closet-sized back rooms that some booths have, or whip out an iPad, and show them comparable works that are available and just as desirable.

Alternatively, a dealer can simply whisk the sold work off the wall and hang up a different one. With the “enormous sale potential at fairs,” as Grossmann described it, why put up a red sticker that costs less than a penny, when you can put another six-figure painting up for sale instead?

Casey Lesser is an Editor at Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment