What We Can Learn from the Brief Period When the Government Employed Artists

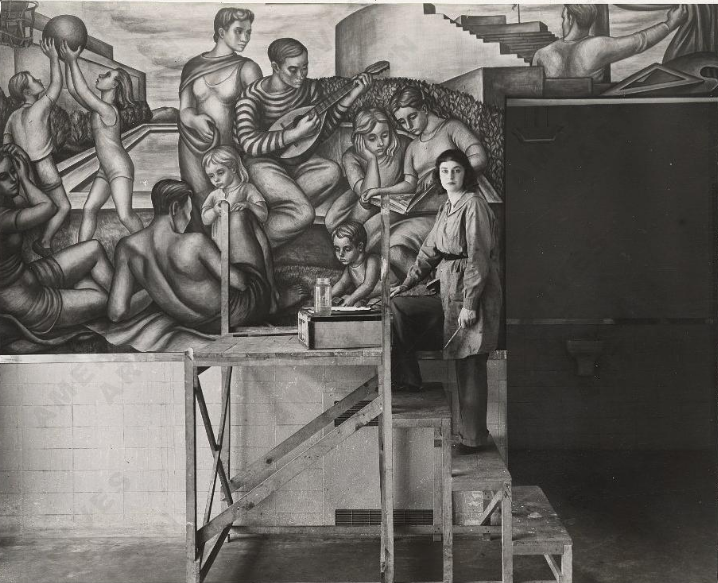

Marion Greenwood with a mural she created for the WPA. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

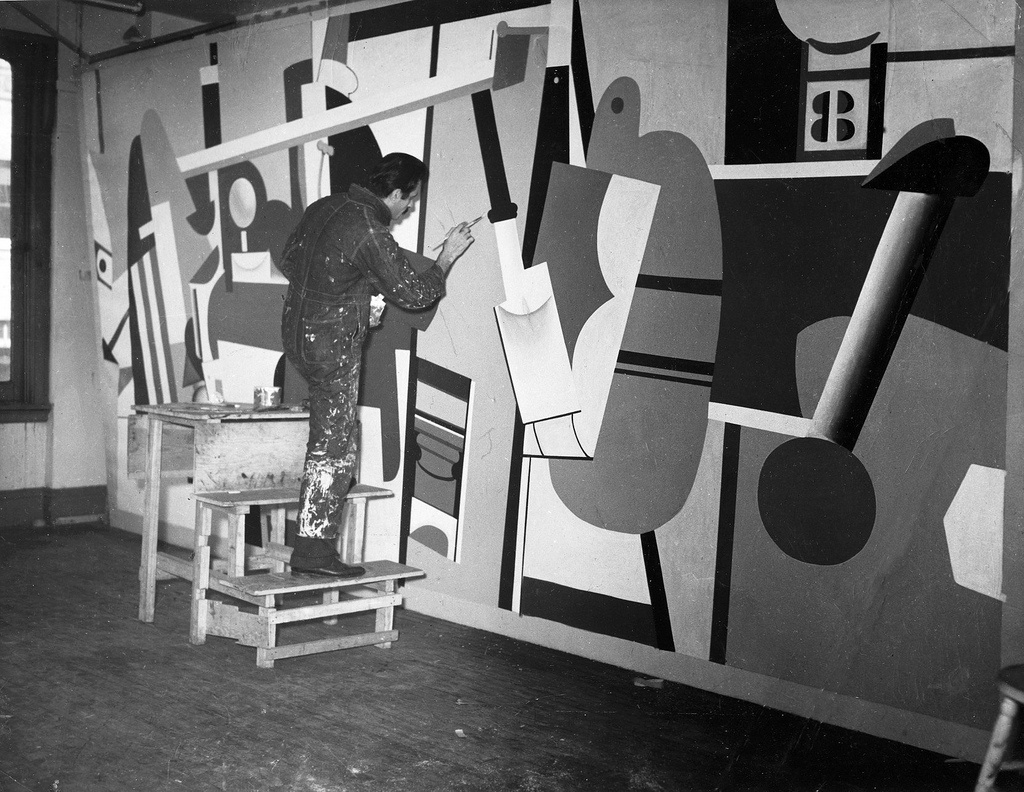

Marion Greenwood with a mural she created for the WPA. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art. Philip Guston working on a mural for the WPA. Photograph by Robbins. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

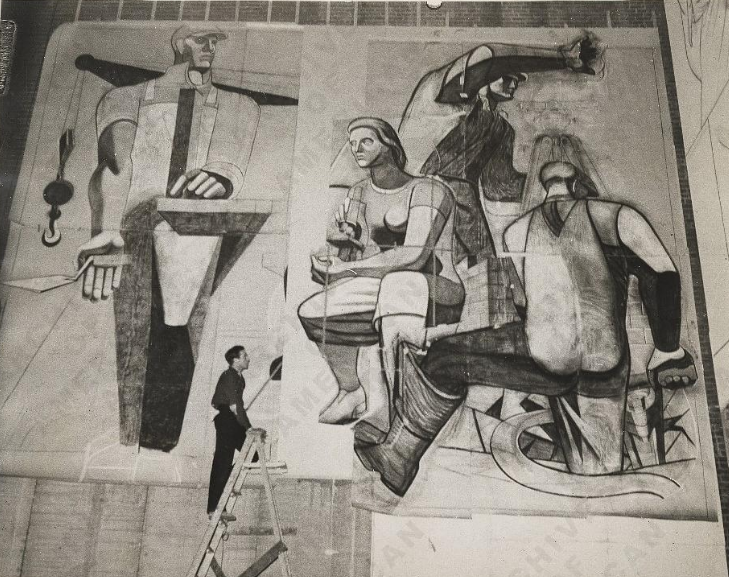

Philip Guston working on a mural for the WPA. Photograph by Robbins. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko are best-known as pioneers of Abstract Expressionism. But all four were also among thousands of artists and other creatives employed by the government through the Works Progress Administration (WPA) between the years of 1935 and 1943. That the arts would be funded significantly by the federal government—never mind that it would actively employ artists—may well raise an eyebrow today. But working under a subdivision of the WPA known as the Federal Art Project, these artists got to work to help the country recover from the Great Depression, as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Evidence of impoverishment and a portfolio showcasing one’s skills and commitment to the arts were all that was needed to qualify for the WPA initiative. This and the Federal Art Project’s non-discrimination clause meant that it attracted, and hired, not just white men but also artists of color and women who received little attention in the mainstream art world of the day. These artists created posters, murals, paintings, and sculptures to adorn public buildings.

Hospitals, post offices, schools, and airports were decorated with some of the roughly 200,000 artworks created through the program. Yet no accompanying agency was established to preserve the works. So following the dissolution of the WPA in the lead-up to World War II, many were destroyed, sold as scrap, or hastily auctioned off with little record—save a small portion that were discovered at a Long Island salvage dealer, bought by a Lower West Side curio shop owner, and repurchased by their artists for three to five dollars a pop, as Christopher DeNoon notes in the book Posters of the WPA.

Reassembling WPA artists’ work

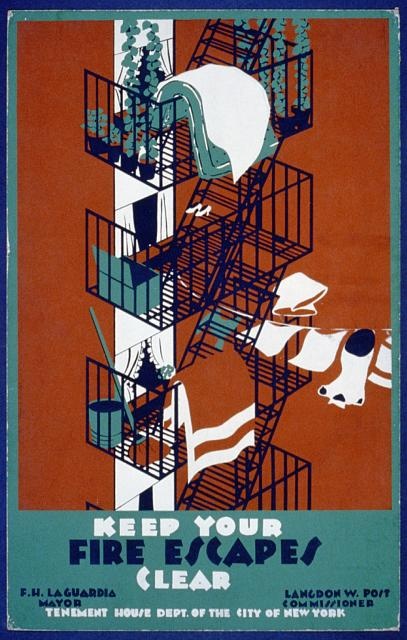

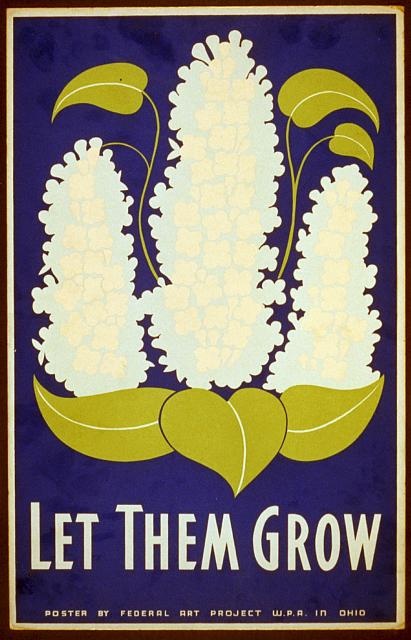

1936 or 1937 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

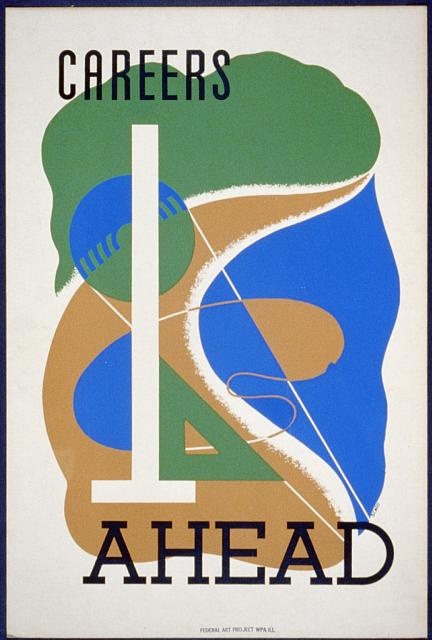

1936 or 1937 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. 1940 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

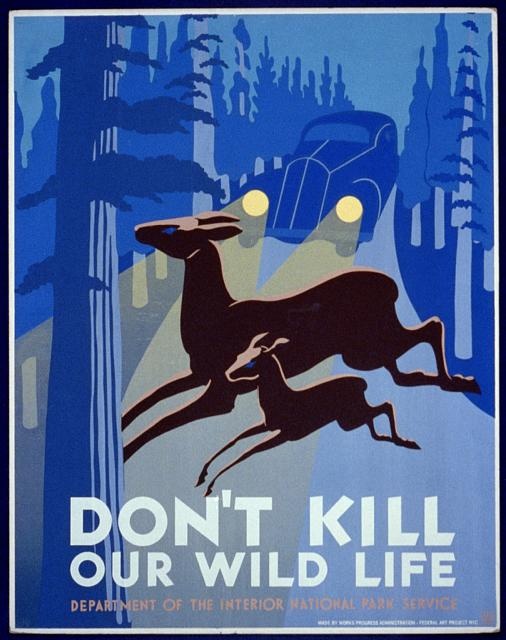

1940 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Poster by Stanley Thomas, Clough, 1938. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

Poster by Stanley Thomas, Clough, 1938. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

In 1965, the late art historian Francis V. O’Connor went in search of artworks created as part of the Federal Art Project for an exhibition about the WPA artists. O’Connor was particularly interested in locating posters. The murals, sculptures, and photographs created by artists under the auspices of the WPA were easier to find. The posters, innately ephemeral, were harder to recover. On the morning of February 15, 1966, as he recounts in Posters of the WPA, O’Connor joined Dr. Alan Fern, then chief of the prints and photographs division, at the Library of Congress. Fern escorted the art historian up “a very dusty, cobweb-festooned, spiral staircase until we came to a heavy door” at the entrance to one of the library’s corner towers.

“Unlocked,” he goes on, “this [door] creaked open to reveal sinister sights and sounds: a large, musty, circular room...stuffed with saw-horse tables heaped with ancient circus posters.” Amid the circus posters and some roosting pigeons, O’Connor and Fern found a large wooden case with a WPA shipping label on it. When pried open, it revealed a cache of immaculate posters. “Of all the art and documentation from this period I have discovered dirtying my hands in unlikely places,” O’Connor wrote, “this find was the most unforgettable.”

1939 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

1939 poster. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Poster by Maurice Merlin, 1943. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

Poster by Maurice Merlin, 1943. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr. Poster created between 1936 and 1941. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

Poster created between 1936 and 1941. Image via Library of Congress on Flickr.

Remarkably, the whereabouts are known of only around 2,000 of the 35,000 poster designs that were produced during the WPA years. Yet art from this era, created for the greater good, deserves prominence in the annals of art history. Graphic, colorful, and easily legible, the posters advertised plays put on by the Federal Theatre (America’s only ever national theater) and exhibitions of children’s art that took place at the more than 100 new art centers created across the country as part of the Federal Art Project. The posters also raised awareness for public health issues, promoted the country’s national parks, and glorified the labor traditions of different states.

Artists were employed with specific goals in mind: to help the government communicate with the rest of the country, to inspire pride in a nation that had been brought to its heels, and to document the country’s recovery effort. In exchange, each artist received $24 per week (approximately $400 per week in today’s dollars).

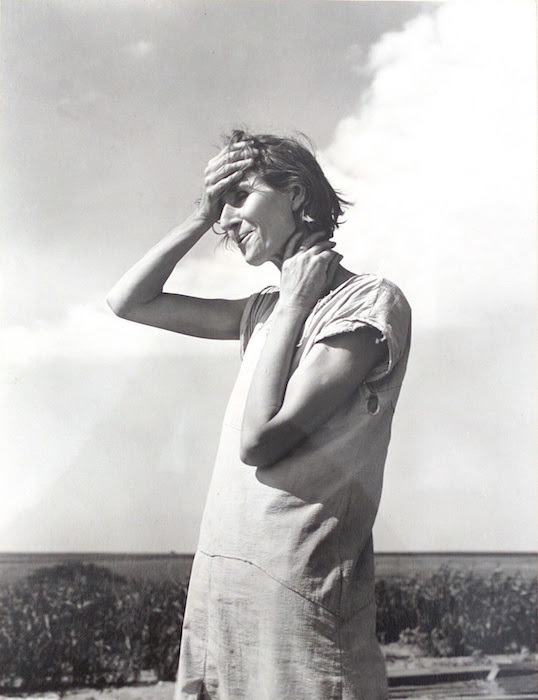

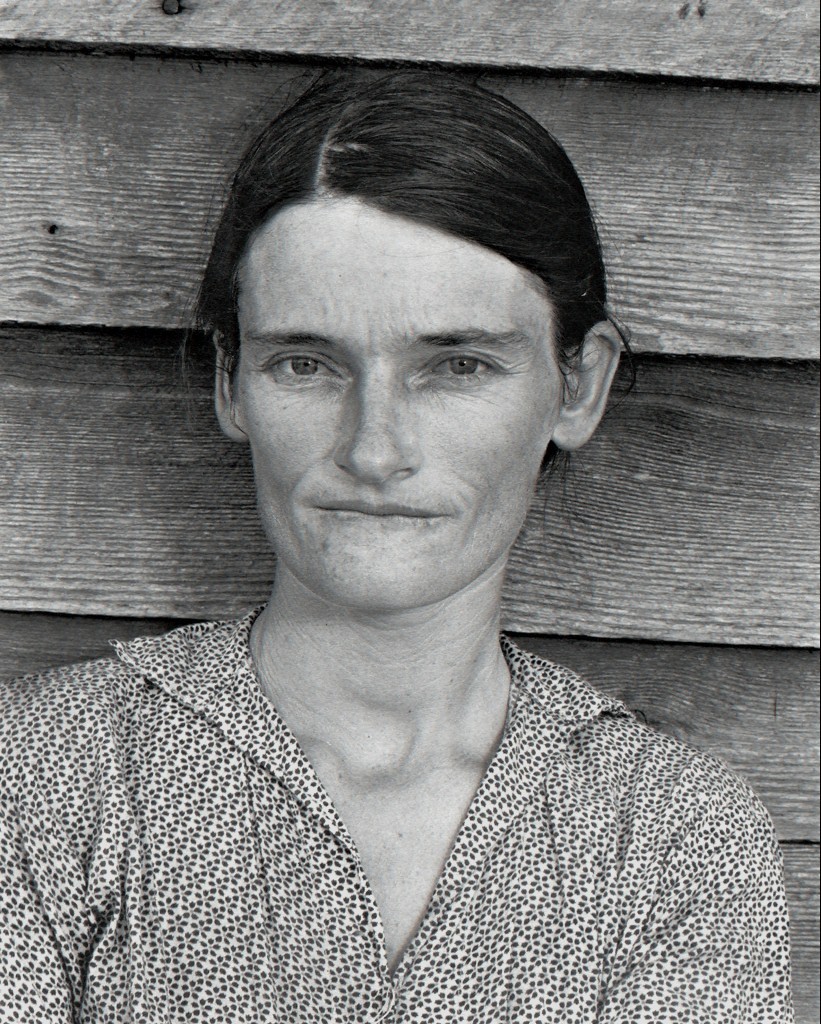

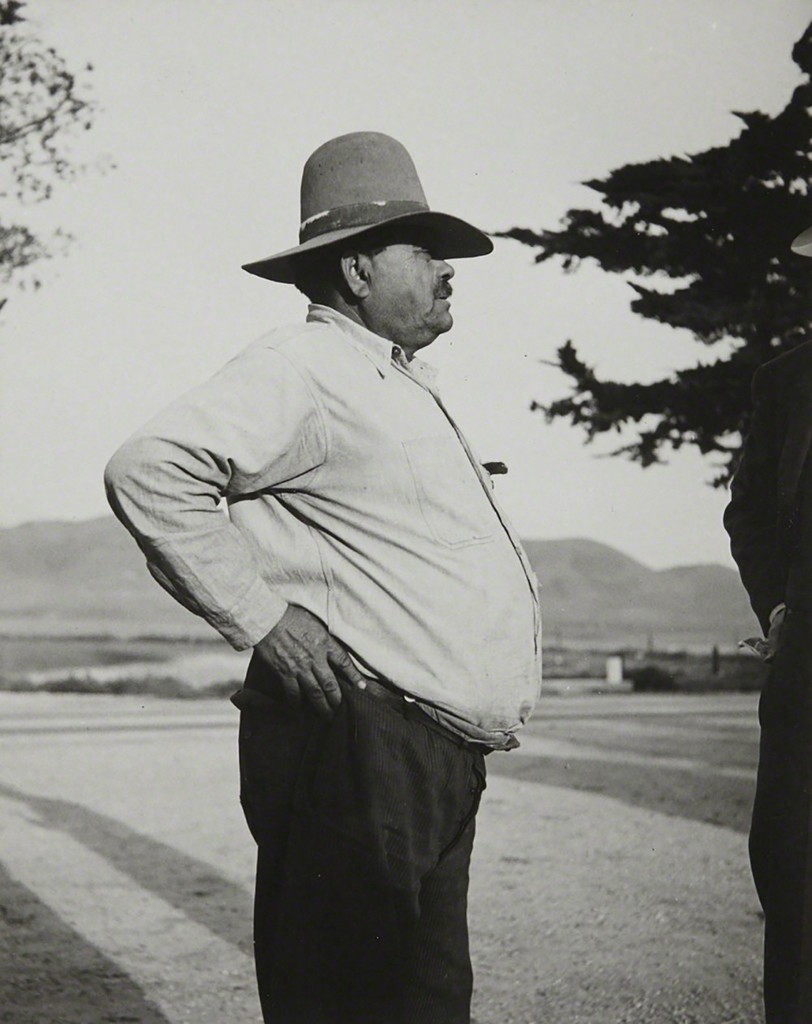

By 1938, the Federal Art Project existed in 48 states. Photographers like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans were famously deployed to Dust Bowl and Rust Belt states, respectively. There, they recorded the poverty and hardships suffered by workers—while also portraying them with a sense of dignity.

A new, diverse class of artists

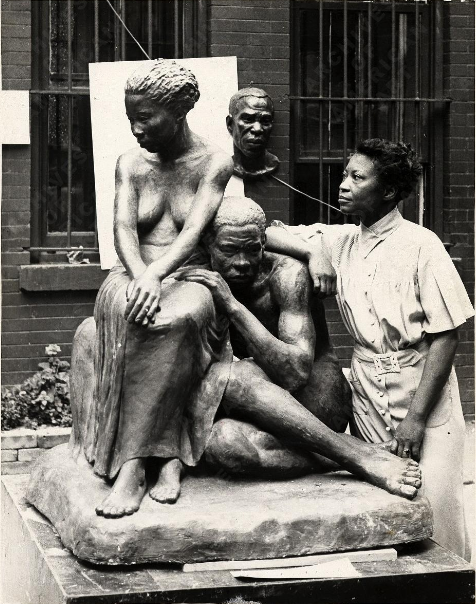

Augusta Savage with her sculpture Realization. Photograpy by Herman. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

Augusta Savage with her sculpture Realization. Photograpy by Herman. Image via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art. Arshile Gorky working on one of the panels for his “Aviation” murals for the Newark Airport. Photo via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

Arshile Gorky working on one of the panels for his “Aviation” murals for the Newark Airport. Photo via Federal Art Project, Photographic Division, Smithsonian National Archives of American Art.

Perhaps the WPA’s greatest legacy was the diversity of its artist pool. In her book Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, Susan E. Cahan writes that “Only during isolated periods, such as the WPA art projects of the 1930s, had African Americans been given nearly the same opportunities as whites through government programs that employed artists.” These programs, she notes, provided support for Aaron Douglas, Charles White, Charles Alston, Hale Woodruff, Archibald J. Motley Jr., Norman Lewis, and Eldzier Cortor, among others.

At the heart of this flourishing period in the arts was a “new generation of plebeian artists and intellectuals who had grown up in the immigrant and black working class neighborhoods of the modern metropolis,” Michael Denning writes in his book The Cultural Front. Anti-fascist emigres poured into New York, fueling the nerve center of the FAP’s work, with a Federal Art Project Gallery opening on West 57th Street in 1935.

The WPA years were perhaps the only successful period in American history when fine art and practical art were one and the same. And crucial to the resulting democratization of culture was a form of expression that addressed the experiences of the working class and was actively shaped by the working class. WPA art favored Social Realism, in the form of public artworks and murals that celebrated industry and labor. These works put art within eyesight of ordinary people going about their daily lives and are consequentially also among the most famous created through the WPA initiative. One such example is Arshile Gorky’s “Aviation” murals for Newark Airport, of which two out of 10 panels survive today.

The Federal Art Project buckles under political pressure

In the 1930s as is the case today, partisan politics resulted in plenty of opposition to the Federal Art Project from Republican Congressmen such as Representative Dewey Short. Short told Congress that good art was the product of suffering artists while “subsidized art is no art at all,” as DeNoon notes in Posters of the WPA. Further fueling the fire, the leftist inclinations of this period, particularly among those engaged in the WPA and other alphabet agencies, led to a belief that the Federal Art Project was a hotbed for Communists.

The WPA’s communist ties were wildly overblown, according to several sources. Nonetheless, in 1937, the WPA was saddled with a regulation stating that it could not employ non-citizens. This led to a significant drop in the number of the artists that the programs employed—and included Rothko, a Latvian, and Willem de Kooning, who was Dutch. Starting in 1939, Representative Martin Dies began an investigation into the WPA’s activities, something which, as DeNoon writes, was “a frightening precursor to the McCarthyism of the 1950s.” Eventually, as World War II loomed, the programs were shut down or channeled into the war effort.

By that time, however, the WPA had left a striking legacy. In producing many thousands of paintings, sculptures, murals, photographs, and posters it pioneering new technical innovations in these cultural fields. It gave numerous important artists a leg up in a desperate time, among them Jacob Lawrence, Alice Neel, and Louise Nevelson. Lee Krasner called the program a “lifesaver.”

Above all, it turned a generation of young American creatives into career artists. “Even in that short time,” de Kooning would say of the project, “I changed my attitude toward being an artist. Instead of doing odd jobs and painting on the side, I painted and did odd jobs on the side. My life was the same, but I had a different view of it.”

—Tess Thackara

No comments:

Post a Comment