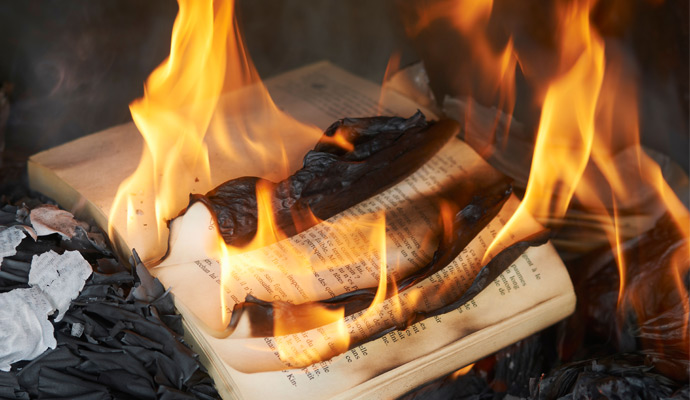

Burn Your Rule Book and Unlock the Power of Principles

The producer of a thought leadership event for senior executives called me recently. She shared with a rueful chuckle that the theme for this year’s meeting was uncertainty: in economic policy, trade, healthcare, international relations…the list went on. I replied that the event would certainly tap into a larger zeitgeist — everyone is wrestling with uncertainty.

Although some argue that there have been more turbulent periods in history, I would respond that these comparisons don’t matter. Perceived turbulence and uncertainty is higher than it has been in several generations. As I’ve discussed in an earlier post, trust in our stabilizing institutions is in decline. A recent article in the Journal of Emergency Managementdocuments the turmoil: The frequency and magnitude of natural disasters is increasing. Although overall violent crime is down in the U.S., complex, coordinated attacks and terrorism are up. Cybersecurity incidents rose eightfold between 2006 and 2012 — and continue to increase. Look outside and street protests, sometimes violent, seem to occur weekly on issues including immigration, healthcare access, and First Amendment rights.

There is no magic formula to quiet the forces of disequilibrium that swirl around us. Leaders, however, can help their followers cope with tempestuous situations by creating pillars of certainty in those areas where they can exert control. In particular, an organization and its leaders can stand for rock-solid principles that consistently guide their thinking and actions over time.

Principles, unlike rules, give people something unshakable to hold onto yet also the freedom to take independent decisions and actions to move toward a shared objective. Principles are directional, whereas rules are directive. A simple example of a rule: “All merchandise returns must be made within 30 days.” Contrast this with Nordstrom’s principle-based approach: “Use your best judgment in all situations. There will be no additional rules.” The former shows no trust in either the sales associate or the customer. The latter is exactly the opposite and encourages the frontline worker to build a relationship with the customer.

It has been more than three decades since Lou Gerstner turned IBM around using what was then a groundbreaking idea: managing by principles rather than procedures. Yet many organizations have been slow to move beyond rule-based approaches.

In some rule-based enterprises, it is the enduring, mythical power of a four-inch-thick procedure manual that lays out exactly what workers can and cannot do. In others, it is accumulated organizational ossification. Of course, there are regulations, union rules, and other legitimate constraints. Too often, however, rules were designed to fix the problems of yesterday and remain in place long after the problem itself has changed.

The result is a disconnect between a need and the ability to fulfill it: “That’s not in my job description.” “I’m not authorized to make that decision.” “I know it doesn’t make sense, but I’m just doing what they told me.” Customers are frustrated — and so are employees. Efficiency and engagement both suffer. Revenue and profit are sure to follow.

Some companies, however, driven by the increasing evidence of the links among purpose, profit, and employee engagement along with the increased need for organizational agility are taking the principle route.

Consider, for example, U.K. upstart Metro Bank and their “One to say yes; two to say no” principle. That is, any frontline employee can decide to say yes to a customer request, but if they think the request should be denied, they must get permission from a colleague or supervisor. That’s a welcome, empowering inversion of the typical approach.

Although such approaches may seem most natural in a B2C setting, B2B companies can benefit as well. When Laura Baldwin took the reins of O’Reilly Media from founder Tim O’Reilly in 2011, the company was shifting its organizational orientation from product lines to audience segments and, perhaps more daunting, building the company up beyond its charismatic founder to thrive.

Baldwin told me that the key was not to try to be the next Tim but rather to involve everyone in aligning actions with aspirations. From this, O’Reilly’s operating principles were born. Some (“Is it best for the customer?”) are lofty and conceptual. Others (“Know your numbers” and “Measure what matters”) are hard-nosed. One of the more intriguing principles: “Embrace, adapt to, and drive change.”

Baldwin said that one of her goals was to provide people with the same set of standards for working together. “Principles give everyone a voice — even outside of their formal roles,” she said. As a universal norm, they level-set between veterans and new recruits. They can even prompt fresh thinking: “If one of our principles is to ‘Look from the outside in,’ then why shouldn’t we try…?”

Principles are not a panacea. Amazon had a public head-butt with its leadership principles after a New York Times exposé portrayed a brutal work environment. CEO Jeff Bezos’s response was that he “didn’t recognize” the company in the article. To Bezos’s credit, he took immediate action to try to better align aspirations with reality, starting with a letter to employees that encouraged them to escalate “callous management practices” to HR or to email Bezos directly. The company has also taken steps to change how it evaluates employee performance.

If you want to help your organization design its own principles, here’s how to get started:

Think about your organization at its best. Dig into the root behaviors, conditions, and other factors that make things work well, and craft principles to reflect and stimulate more of this positive energy. Ask yourself: What happens when my people are at their peak? Do they demonstrate initiative? Do they feel free to exercise their best judgment? Do you feel a jovial collegiality even when things are tense?

Be ready to live your principles, even when it gets tough. Actions will always speak louder than words. As a leader, realize that the drumbeat for revenue and profit is constant. You have to ensure that the other principles get as much attention as those bedrock goals, and that in practice they fulfill their intention.

At O’Reilly, part of Baldwin’s job is to balance the needs of the customers, the shareholders, and the employees. “If it’s great for the customer but hurts employees, that’s not good,” she said. “It’s one of the reasons we have a principle about generosity and reciprocity.”

Make the principles public. Baldwin noted that O’Reilly’s operating principles are posted in every conference room. “Visitors always stop to read them,” she said. “And the reaction is overwhelmingly good.” Encourage employees to refer to the principles to explain why they made certain decisions. The more they are part of daily life, the greater impact they’ll have.

Baldwin offered some final advice: Don’t expect to be perfect. O’Reilly’s principles have evolved over time. “We don’t always get it right, and that’s OK,” she said. “We can always do better next time.” That sounds like a great starting principle for any organization.

No comments:

Post a Comment