When Collectors—Not Curators—Dictate Art History

Photo by Matt Cardy/Getty Images.

Photo by Matt Cardy/Getty Images.

Walk up the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s famous Fifth Avenue entrance; keep heading straight ahead. Go through the Great Hall and medieval art galleries, pass under a massive choir screen, and then you’ll glimpse it: a brightly lit, angular pavilion at the end of a span of darkened rooms. A few more steps and, as if crossing through a wormhole, you’ve moved from the middle ages into a high-ceilinged space of Renoirs, Seurats, and other work from the 19th century.

This isn’t an unexpected experience at the Met, where decades of history are displayed feet apart. But strolling through the space, one might ask why this curious room at the back of the Met shows work more at home in the Impressionist galleries upstairs; why are there dazzling medieval artworks in a series of back galleries rather than in the darkened rooms leading up to this space; and why, oddly, but enjoyably, does one of the galleries, in the style of a homely living room, have a frumpy couch?

Known as the Robert Lehman Collection, the hundred or so works on view in these thematic rooms stem from the acquisitions of one man who bequeathed them to the Met in 1969. The terms of Lehman’s will required that a portion of his collection of some 2,600 pieces, spanning thousands of years and numerous styles and media, be on display for perpetuity.

The Robert Lehman Collection’s museum within a museum is far from alone in having been given to and accepted by a museum on the condition of display terms. More recent, though not as stringent, examples include the Fisher Collection, given in a long-term loan to SFMOMA in 2009, and a donation from Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson to the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015.

These gifts have each brought an influx of significant work out of private homes or storage units and into the public domain. But whether the terms attached to them ultimately help the receiving museums’ overarching mission to serve the public, or hurt that goal by hindering the ability of curators to freely exhibit artworks, remains a subject of fierce debate.

Seeing a Collector’s Vision

Though the pieces from the Lehman Collection can be temporarily loaned to other places in the museum, over the years there have been a number of public and private calls to permanently assimilate the pieces with the rest of the museum’s holdings. Art historian Robert Storr is among those critical of museums accepting display terms attached to gifts. He argues that curators should have the freedom to display work as they see fit.

“Those works are hostage to that particular collector’s vanity, and the public can only see them under certain circumstances,” he said.

Others, however, say that such terms allow the public to see a wider selection of work than they otherwise might. The Robert Lehman Collection’s former curator and current chief curator of the Yale University Art Gallery, Laurence Kanter, argues that integrating the Lehman collection into the rest of the Met’s holdings wouldn’t add value for the public.

“What the Met would do is pick off the trophies and everything else would go in storage,” he said. “Who wins with that?”

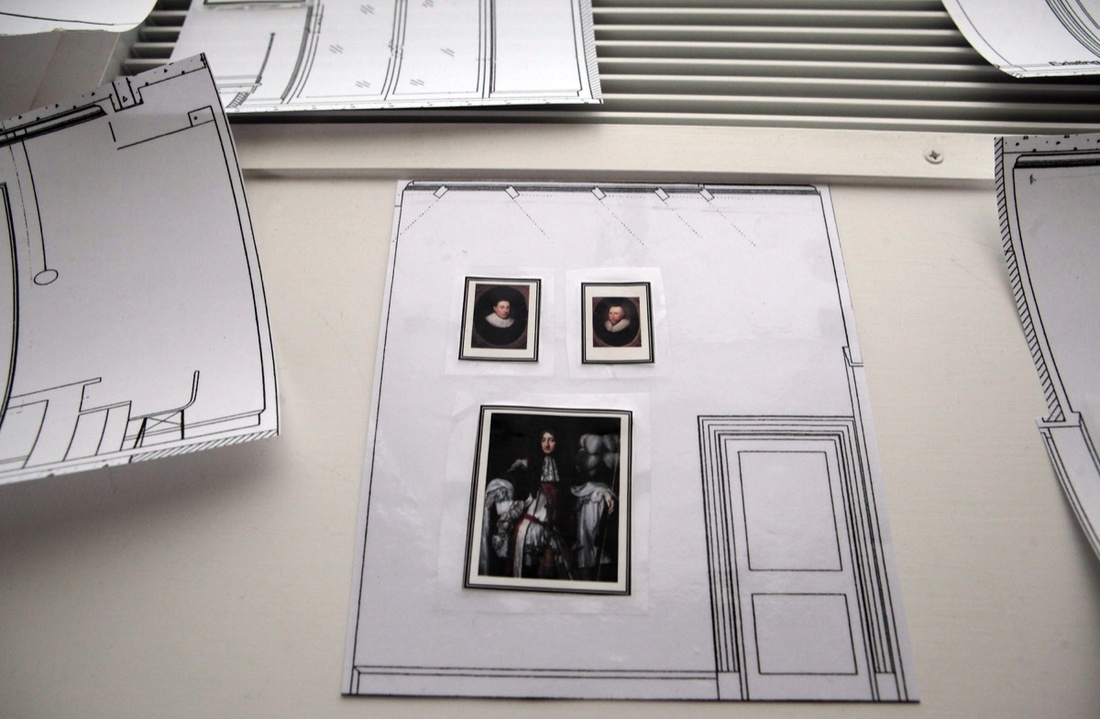

Kanter noted that the collection is, in fact, curated. For example, he oversaw an effort to remove “goofy” furnishings the Met originally included to recreate Lehman’s house and instead moved to display the work in rooms that offer an intimate but more more general approximation. Nonetheless, the singular view on unique objects provided by collectors is, Kanter argues, unique and should be preserved.

“It’s mostly the collectors—not museums—who revel in the intrinsic quality of objects and the personal experience of them,” he said. “I think it’s one of the great experiences available to American audiences that in some museums around the country, you can share that.”

- View of the Edlis/Neeson Collection. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

A Nuanced Question

Unlike the strictly governed institutional practice of deaccessioning work, there are few firm rules for institutions on whether or in what cases to accept collections with strings attached. The Met, for example, states on its website that it generally does not accept donations with terms. But it and other museums like it are free to craft their own rules but can also make exceptions if needed. Observers say this flexibility is important given the reality of donations and the fact that, as museum acquisition budgets shrink, gifts have become the main avenue for adding masterpieces to public collections.

“Decisions on accepting a gift of a collection or singular work of art need to be assessed on a case by case basis, and reflect the best interests of the museum, art, and donor,” wrote Christa Clarke, president of the Association of Art Museum Curators, an advocacy group that sets standards for its profession, in an email.

“There’s a kind of dance that has to go on, if you will, between the private collector and the public institution,” said Jeffrey Cain, a founding partner of the consulting firm American Philanthropic.

When offered a donation with terms that limit unencumbered curatorial freedom, the director, the board, and often the curators of an institution weigh numerous factors in deciding if to accept it. These include the prominence of the works, the duration the works must be exhibited, and what, if any, gaps exist in the museum’s own collection.

Recent donations to major public institutions that have included display terms haven’t been nearly as restrictive as the Lehman Collection’s but have still generated attention.

The Art Institute of Chicago’s acceptance of 42 works by artists including Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, Cindy Sherman, and Jeff Koons significantly bolstered its contemporary collection. But the donation came with the condition that the approximately $400 million in art stay on view for 50 years. For the first half of that time period, they must be shown together in the museum’s contemporary galleries.

The terms, which were disclosed in the press release announcing the donation, were key in helping the Art Institute of Chicago win the donation. “I have donated works of art to museums for years but have been frustrated by their lack of exposure,” said Edlis, echoing a sentiment felt by many collectors who attach display conditions out of concern that their work will wind up in a basement.

In an email to Artsy, James Rondeau, president and director of the Art Institute of Chicago, firmly rejected the idea that the terms amounted to a burden on curators in a way that would set art history in amber, arguing that showing the works bolsters the museum’s ability to craft narrative through contemporary art and that the ultimate beneficiaries of the pieces are its audiences, artists, and the public.

“We made our selections precisely because these are works of art we will want—and we believe future stewards of the collection will want—our visitors to experience,” Rondeau wrote. “Stefan and Gael have given us total freedom to lend these works to other museums, and to rotate for conservation purposes,” he added, calling the collection “dynamic, not static.”

Indeed, when museums are accepting gifts with terms attached, collectors and institutions often think far into the future. There is, for example, a significant difference between a gift with display conditions that extend in perpetuity versus those with shorter restrictions. Adrian Ellis, founder of AEA Consulting, which offers services in the cultural and creative industries, urges taking a long view when donations are restricted for even a few decades given museums are supposed to exist for centuries.

“Sucking it up for 20 years isn’t the worst thing in the world, to put it bluntly,” he said.

Why Collectors Include Terms

Multiple individuals interviewed for this story suggested that the practice of donating works to institutions with terms attached is on the rise. However, Diana Wierbicki, global head of art law at law firm Withers Worldwide, said that in her nine years directly facilitating such transactions, there hasn’t been a discernible uptick.

Headlines may be deceiving, she suggested: They most often cover major donations of huge collections, which, in turn, provide donors the most leverage in a negotiation with a museum. These donations are, however, a rarity compared to one-off gifts that infrequently make news or attract attention but provide crucial depth to institutions.

Wierbicki said that what motivates most of her clients to attach terms to their gifts is a genuine passion for the works they’ve assembled. “They want to give the public the most benefit from that art,” she said. Some collectors support work, which mainstream institutions show all too rarely and might be pushed to exhibit more, further compelling them to get assurances from institutions that the public will see the works. Wierbicki said this is particularly true when it comes to art by women.

“The donors really care about the cause,” she said. “They’d really like to see these artists displayed and not have work go into storage.”

Storr said, however, that even when applied with good intentions, applying strict terms to donations can actually undermine—rather than solidify—a collector’s legacy over time. This is especially the case if the terms imperil the ability of an institution to survive financially or make sound curatorial choices.

The former senior curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA said he turned down donations while at the museum because of the terms attached and he argues that directors need to “stand up” to collectors, for their own good and for the long-term benefit of the institution under their care.

“Collectors do not always know best,” Storr said. “And if the idea is to get yourself a place in history, who wants to have a place in history that makes you look bad?”

Installation view of "Approaching American Abstraction: The Fisher Collection exhibition." Photo © Henrik Kam, courtesy of SFMOMA.

Installation view of "Approaching American Abstraction: The Fisher Collection exhibition." Photo © Henrik Kam, courtesy of SFMOMA.

Transparency

SFMOMA expanded dramatically to house the collection of Donald and Doris Fisher, a long-term loan of 1,100 works by masters of the post-war era including Warhol, Richard Serra, Ellsworth Kelly, and Anselm Kiefer. It represented a stunning increase in art available on public view to those in the Bay Area, though the collection has been critiqued for lacking diversity. The museum doubled in size, moving to a new building at a cost of $305 million. Yet, according to San Francisco Chronicle art critic Charles Desmarais, there should be great transparency around the terms. Especially since those who visit the museum may not be aware that part of the selection of works they’re viewing was a stipulation of that gift.

Seventy-five percent of the Fisher Collection galleries, which span 60,000 square feet and three floors of SFMOMA, must be comprised of works from the collection. And a monographic show dedicated to the collection must go up once every 10 years. Greater transparency, Desmarais argued, is warranted about these and other terms.

“Simply put, as you enter the Fisher galleries, it should say precisely what the deal is,” he said.

Those inside the institution have long asserted that they have the flexibility needed to ensure the Fisher galleries remain fresh. “There are so many possibilities about how to approach this collection,” Gary Garrels, senior curator of painting and sculpture, previously told Artsy. “Some much more unorthodox ideas are already bubbling for future rotations.” He also noted that the Fisher Collection’s donation has also helped spark additional gifts from other collectors.

But, outside of SFMOMA, obversevers note that transparency is an important part of any major gift. “I see no intrinsic evil in accepting donations whatsoever,” said Ellis. “But you need to be very clear about the terms of donations.”

Even with transparency, Storr argues that limitations on how works are displayed privileges the collector over the work itself in ways that undercut a museum’s responsibilities. Curators need to be able to “shuffle the decks regularly, rewrite art history on the walls, and make comparisons” in ways that challenge the canon and integrate disparate materials.

Though a gift to a public museum as monumental and encumbered as the Lehman Collection is perhaps a thing of the past, the question of how the terms attached to it and other donations shape what art is seen remains one viewers should ponder—perhaps while they sit on an overstuffed couch.

—Isaac Kaplan

No comments:

Post a Comment