Is Art an Object of Passion or an Asset Like Any Other?

As the global ultra-rich snap up trophy artworks and build collections scattered around many homes and storage facilities, art services are becoming an increasingly important part of wealth professionals’ offering to help these collectors manage their financial lives.

A Thursday panel at Deloitte’s U.S. Art & Finance Conference at The Armory Show featured five art and finance professionals discussing the evolving relationship between art and financial services.

It launched with Philip Hoffman, founder and CEO of The Fine Art Group, harking back 18 years to when he was planning the launch of his art investment fund, The Fine Art Fund. Hoffman recalled how at the time, “everyone said it was very crude” to approach art as an asset class, since “art was about passion.” Fast-forward 18 years and now everyone’s doing it, he said, ticking off the names of banks with art services departments.

How did that point of view evolve? One reason is the sheer scale of the value of artworks today. Art transactions have recently accounted for over $60 billion annually. That doesn’t mean all or even most collectors go in with an investment mindset—everyone on the panel stressed that collecting begins with a passion for art. But, said Henry Johnson, vice chairman for the East Region at Northern Trust Wealth Management, sometimes a collection “grows to such a size that you can’t ignore it.” For Johnson, that threshold is roughly 20% of a family’s or individual’s net worth, rather than an absolute number. For example, he’s met families with $50 million art collections who aren’t even thinking about it as an asset.

Leon Bailey, chief financial officer at the Duncan Family Office, said that while his clients collect art on a very personal level, they have over 900 artworks, enough to make the collection account for a serious portion of their wealth. Part of his role is to help track, maintain, and insure the works.

Evan Beard of U.S. Trust/Bank of America Private Wealth Management said his own bank has seen its art lending portfolio grow from $1 billion to $6 billion. One of the key enablers of growth in art-related financial services was the increased comfort and interest on the part of his colleagues in the underwriting and risk-management teams, thanks to the growth and depth of the auction markets.

Beard needled fellow panelist Brook Hazelton, president of Christie’s in the Americas, for offering in-house advisory services to clients that he said are inevitably biased towards a sale. But he said he was grateful for the service auction houses provide: creating a publicly available data set the bank and others can use to understand prices and underwrite loans. In a separate conversation with Artsy, he contrasted today’s environment, with its vast online repositories of pricing data, with the 1980s, when looking up data meant dusting off a bunch of old binders at Sotheby’s.

He described art and other tangible assets such as cars and yachts as the last frontier for clients who have financialized nearly every other aspect of their lives, throwing out an estimate of $1 trillion in tangible assets that every bank is keen to help lend against. “That’s a nut we’re all trying to crack,” he said.

What do these already wealthy people do with their art-secured loans? Beard said he’s seen his clients use the capital raised against their art (typically done at a 50% loan-to-value ratio) to buy more art, to scale up their philanthropy, or to reinvest in their existing businesses. He mentioned a real estate developer who leveraged his art to build cancer centers that will house the collection, a woman who used her art collection to raise the cash to sue her husband in the middle of divorce, and another developer who built enough hotel rooms in his city to host the Super Bowl.

“People are now using it as an internal source of liquidity,” he said. The bank, he said, sees art more as a capital asset than an investable asset, meaning they feel comfortable lending against it, but wouldn’t invest in it with the intention of profiting off a later resale.

Of course, art prices do go up, and that’s another reason art specialists have a role to play in broader wealth management. Johnson described an increasingly common estate planning scenario, in which parents bequeath art to their children based on sentimental attachment. He told one story of a couple who bought two paintings for $500,000 each in the 1970s. They left one, a Frank Stella painting, to one son who went on to become a teacher. The other, Clyfford Still painting, went to the other son, who went on to become a private equity titan. But the Stella is now worth $10 million, while the Still is worth $45 million. He said estate planning that includes specialized art knowledge can help foresee and plan for such eventualities, so as to avoid conflict within the family later on.

That also raised the question of value. Hoffman asked how people could feel comfortable wading into a market where two similar-looking paintings can fetch prices hundreds of thousands of dollars apart. Even if they get a discount, what are they to make of the initially quoted price? How can they move past the information asymmetry, or the conflicts of interest posed by art advisors or dealers who are motivated to make a sale at all cost?

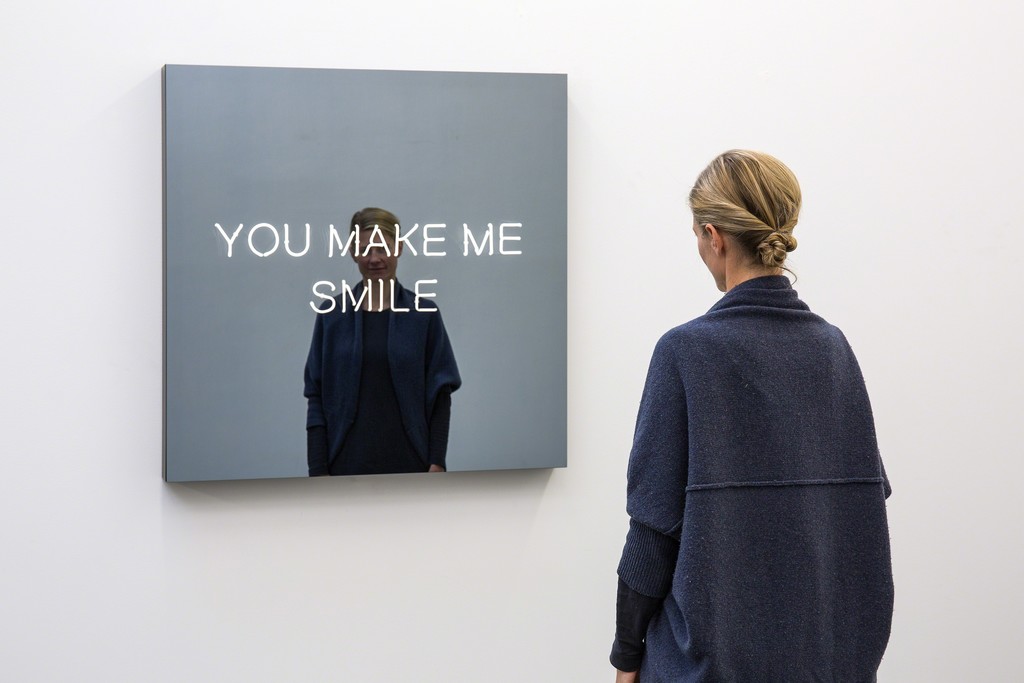

Part of the answer is trusting your gut, said keynote speaker Anne Dias Griffin, in her opening address. In many ways, amassing an art collection requires the same skills as those of a successful investor. Griffin, founder and managing partner of Aragon Global Management, and a former investor under George Soros, is a prominent Chicago-based collector formerly married to hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin. Both collecting and investing reward pattern recognition, the ability to carefully assess value, and due diligence, but they diverge in one respect: Art collecting is “a really personal endeavor,” she said. A collection “grows into a form of self-portrait.”

“Take risks, make bets,” she said. “If you’ve trained your eye, you will know when it’s right to go for it.”

—Anna Louie Sussman

No comments:

Post a Comment