With Just Four Paintings to His Name, This Renaissance Master Changed the Course of Art

At first glance, organizing a major exhibition dedicated to the Renaissance master Giorgione may have seemed like the art world’s version of “Mission: Impossible.”

While he is credited with introducing stylistic and technical innovations that would forever change the course of art, paving the way for Titian’s masterpieces, only about 40 paintings attributed to Giorgione still exist today. Of those, some particularly exacting historians believe that only four are truly by his hand. And if this hotly contested body of work wasn’t challenge enough, biographical information concerning Giorgione is so scarce that we know more about the moment he died than the entire course of his life. So, the stakes for putting on a show of such an artist are understandably high.

This was the mission—and in the spring of last year, London’s Royal Academy of Arts chose to accept it. “The fact that we know so little about the enigmatic figure of Giorgione was perhaps the most challenging aspect of staging this exhibition, yet also the most exciting,” curatorial assistant Lucy Chiswell told Artsy over email. The Academy’s show, “In the Age of Giorgione,” gracefully sidestepped these issues of attribution and scarcity by widening its scope to encompass the entire circle of artists working in Venice during the first decade of the 16th century. Titian, of course, but also Giovanni Bellini, Albrecht Dürer, Sebastiano del Piombo, and Lorenzo Lotto all made an appearance.

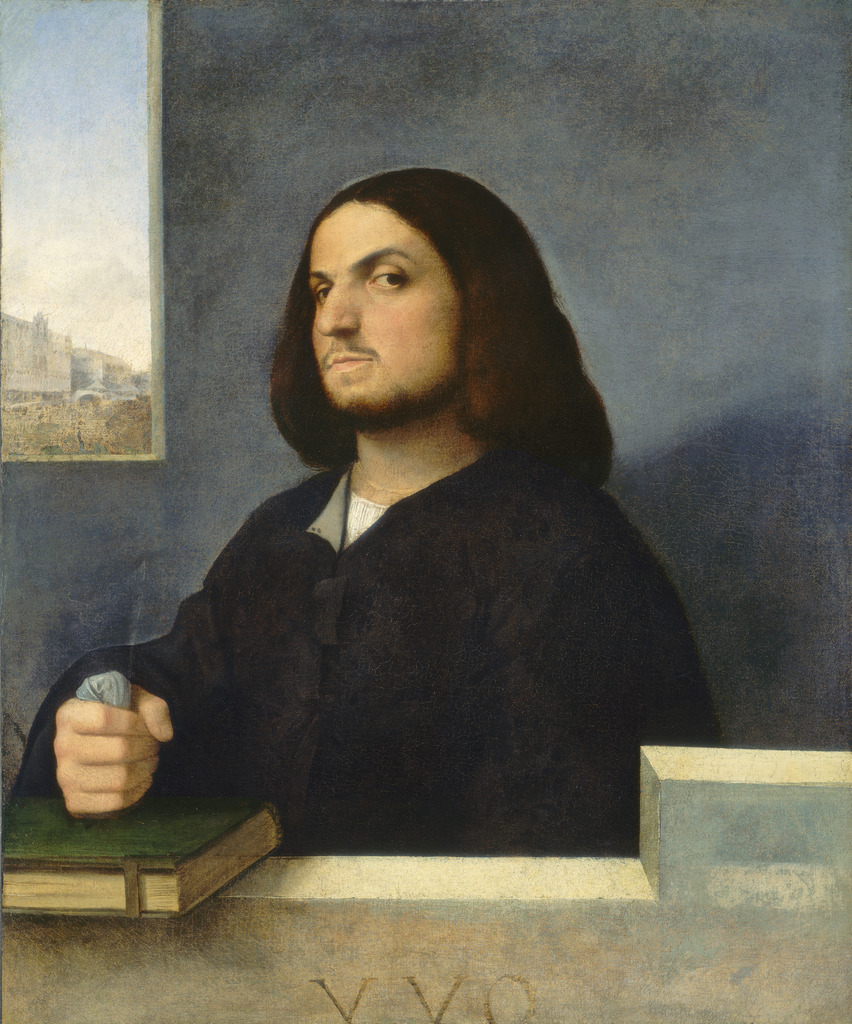

And in a nod to the historians’ endless back-and-forth on questions of authorship concerning Giorgione’s oeuvre, the show asked visitors to weigh in. Portrait of a Young Man (1497–1499), for example, has been variously labelled as a Giorgione and a Titian, with leading experts on both sides of the debate. The exhibition presented arguments for each artist and allowed viewers to vote (Giorgione won, 55 to 45 percent).

While Giorgione will always remain a shadowy figure in art history, we know enough to sketch a rough biography of the Italian painter, who died in his early thirties. He was born around 1478 in the Veneto town of Castelfranco. And we know that at some point he moved to Venice—he died there in 1510 of the plague. Legend has it that he was a handsome, talented musician who, as Vasari wrote, “sang divinely” and played the lute. He was also likely a large man, as Giorgione translates to “Big George.”

“I have always thought it rather apt that we know so little about Giorgione, as I think he would have liked it that way,” Chiswell said. “Mysterious even to his contemporaries, it seems that Giorgione was an artist who liked to ‘cover his tracks.’

Perhaps unsurprisingly, his art is often as inscrutable as his backstory. Highbrow Venetian collectors loved to puzzle over his paintings, in which “clues to a work’s meaning can be cryptic,” according to Chiswell. His most famous painting, The Tempest (1508), depicts a partially dressed woman nursing a baby while a soldier (or a shepherd, or a Venetian noble, depending on who you ask) looks on. A storm brews in the background, with lightning flashing overhead. Beyond the inventive subject matter, what’s revolutionary about these works is the way they privilege atmosphere over meaning. For Giorgione, the landscape was as much a character in his paintings as the actual human figures.

Chiswell points to another painting from the exhibition, titled La Vecchia (ca. 1506), as a prime example of these characteristics. “A painting of an elderly lady? An allegory of the passing of time? Giorgione’s mother? Much has been surmised.” Regardless of meaning, however, “the realism, the use of light, and the window-like eyes that open onto a mind weathered by experience, pre-empt work by such 17th-century artists as Rembrandt, Caravaggio and Velázquez, all painting a century or so later,” she said.

Today, Giorgione’s legacy is composed mostly of echoes. But when those echoes are masterpieces by Titian or later, Rembrandt, it’s a powerful reminder of genius—lost, perhaps, but not forgotten.

—Abigail Cain

No comments:

Post a Comment