The Inventor of Morse Code Really Wanted to Be an Artist

ARTSY EDITORIAL

BY ABIGAIL CAIN

FEB 8TH, 2017 4:25 PM

Samuel F.B. Morse, Gallery of the Louvre, 1831–1833. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Samuel F.B. Morse, Gallery of the Louvre, 1831–1833. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In 1832, following a three-year European tour, Samuel F.B. Morse sailed home to America. Tucked away in the hold was Gallery of the Louvre (1831–1833), a massive six-by-nine-foot canvas that would take him 14 months to complete. Morse intended for the painting, which depicted some three dozen of the Louvre’s greatest works displayed together in an imagined museum gallery, to serve as a sweeping art history lesson for the American people. This painting, he was certain, would finally propel him to fame.

But as it turned out, his true masterpiece—the creation that would earn him international celebrity—was not a painting at all. Morse began to dabble in electromagnetics after his stay in Europe, in experiments that would eventually lead to the invention of the telegraph. He sent the first message, “What hath God wrought?”, from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore in 1844; the words have since become indelible. His name graces the language of dots and dashes still in use by radio operators today.

“His painting career got completely overshadowed by the telegraph, which was earth-shattering,” explained Morse scholar Paul Staiti, a professor at Mount Holyoke College. “The telegraph was the first time that communications and travel became different things, so Morse is rightfully famous for that. But he did have a substantive artistic career, especially in New York.”

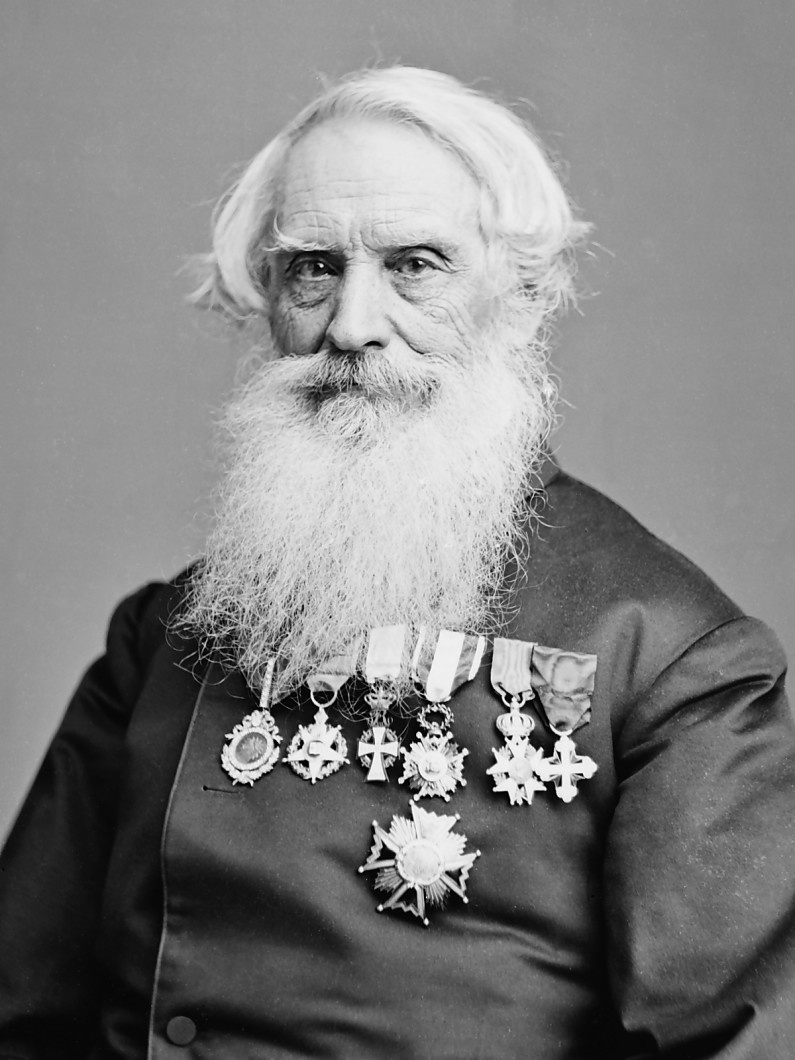

Samuel F.B. Morse. Image: Library of Congress

Samuel F.B. Morse. Image: Library of Congress

Born in Massachusetts in 1791, Morse studied mathematics and philosophy at Yale, where he enjoyed painting miniature portraits far more than attending class. After graduation he decided to focus on the arts, studying first under painter Washington Allston in Boston and then Benjamin West at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Morse developed a taste for Romanticism in England, even garnering praise for a monumental painting of Hercules in the throes of death.

Upon returning home to the United States, however, the artist experienced a rude awakening. The history paintings he had fallen so in love with in Europe—ones where mythological or historical events were transformed into classical, idealized scenes—were of no interest to Americans. “His training is basically a Royal Academy, 18th-century model,” said Staiti. “He has to inject himself into 19th-century America, which is just different. And so it’s a rocky road for him making ends meet.”

Morse was forced to return to portraiture, earning a living by memorializing prominent Americans such as John Adams and Eli Whitney. Despite the status of his sitters, Morse found the work deeply unfulfilling. “He’s hoping for something grander and bigger, and he tries it,” said Staiti. “The Gallery of the Louvre is an example of his putting his eggs in one basket. And it doesn’t do well.”

Morse wasn’t the only American artist of his generation to completely misread his audience. In 1832, Horatio Greenough was commissioned by Congress to create a memorial to George Washington for the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. The sculptor took cues from ancient Greece, modelling the first president after Zeus and clothing him in a toga and sandals. Washington’s bare chest roused both public ire and mockery. Nathaniel Hawthorne joked, “Did anyone ever see Washington naked? It is inconceivable.” The statue soon got the boot, moving to the less prominent east lawn in 1843.

Artists like Morse and Greenough saw their failure as a direct result of lowbrow U.S. culture. “There’s a kind of chronic disappointment in the lack of American culture, the lack of American refinement,” said Staiti. But the public shouldn’t necessarily bear the blame. “Looking at it the other way around,” he noted, “those artists never really hit the nail on the head on what works in America.”

Today, Morse and his compatriots mark a forgotten chapter of art history. “Morse is a major artist, to be sure, but he’s in a generation that’s sandwiched in between the great late 18th-century painters”— including John Singleton Copley, John Trumbull, and Charles Willson Peale—“and, on the other end, the emerging Hudson River School,” Staiti said. Morse’s group, including Thomas Sully, his former teacher Allston, and John Vanderlyn, “all had big ideas, but they didn’t really find a very good audience for them.”

Schoolchildren visit Horatio Greenough’s statue of George Washington. Image: Frances Benjamin Johnston, c. 1899, Library of Congress.

Schoolchildren visit Horatio Greenough’s statue of George Washington. Image: Frances Benjamin Johnston, c. 1899, Library of Congress.

In his efforts to elevate American culture, Morse is credited with a major development in the burgeoning New York art scene. “There are certain expectations held by him and others that this new country, liberated from Britain, is now going to flourish. It’s going to become the next Athens,” Saiti explained. “Except by the time he quits painting in the 1830s, it’s pretty clear to him and others that it isn’t going to be Athens. So he’s asking himself, what can he do to help push this cause ahead to make America culturally great?”

As Morse looked around, he realized all of the American art academies of the time were run by elites. In response, he and a group of artists founded the National Academy of Design in New York, which for many years was one of the only places in the city where artists could display their work publicly. Staiti, reflecting on its influence, asked: “Would the Hudson River School have existed without Morse’s National Academy? I don’t know. The two things went hand in hand.”

Whatever Morse’s contribution to the greater arc of American art history, in 1837 he gave up on his personal practice in a fit of despair. Not only had Gallery of the Louvre been a flop, but he hadn’t received a commission for the series of paintings in the capitol’s rotunda.

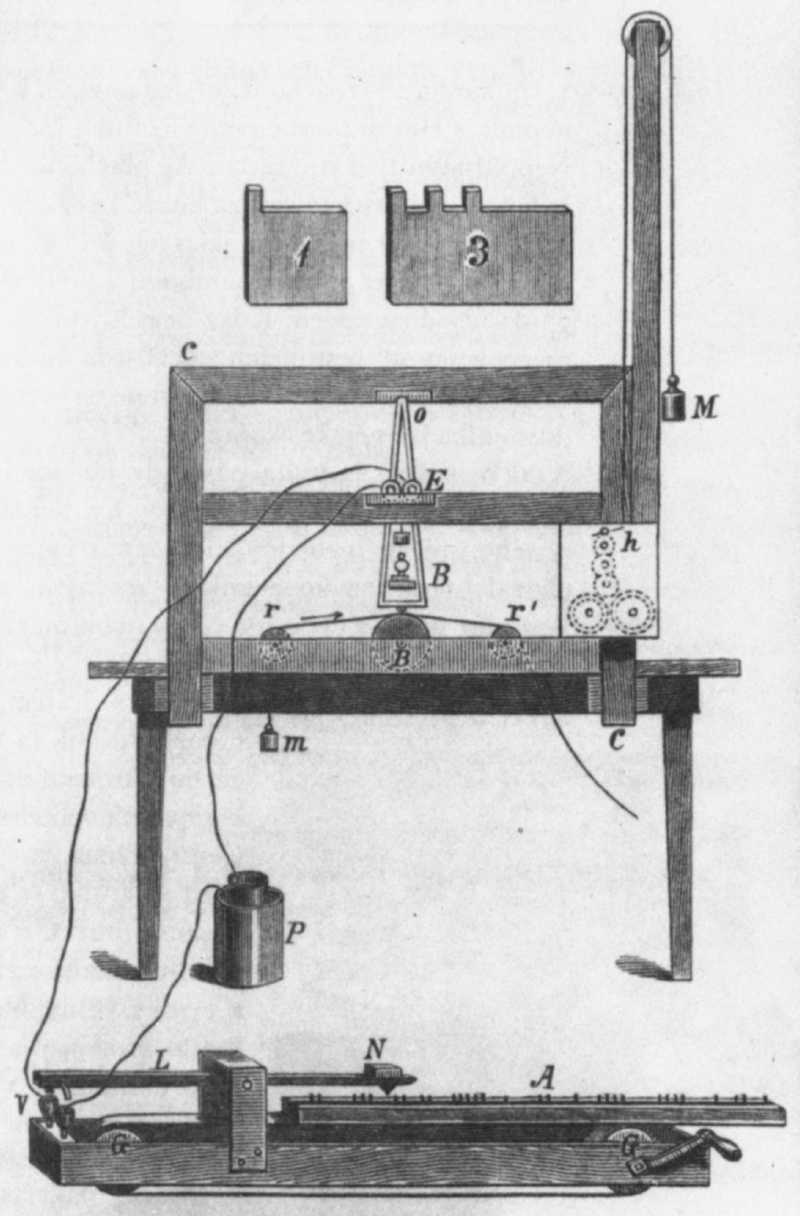

The patent for Morse’s telegraph. Image: Wikimedia Commons

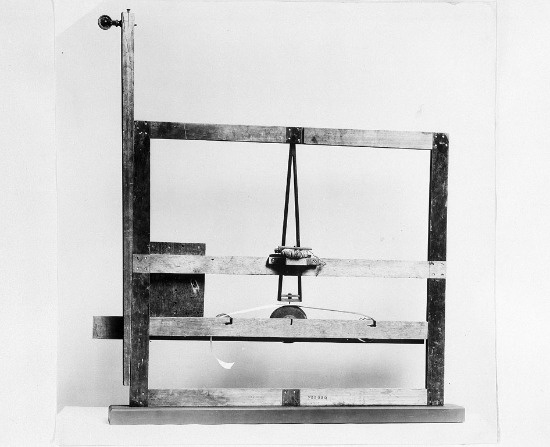

The patent for Morse’s telegraph. Image: Wikimedia Commons Morse's 1837 telegraph receiver prototype, built with a canvas-stretcher. Image: Smithsonian Institution Archives

Morse's 1837 telegraph receiver prototype, built with a canvas-stretcher. Image: Smithsonian Institution Archives

Instead, inspired by a Boston scientist and physician he’d met on the ship back from Europe in 1832, he began to fiddle around with electromagnetics. Fittingly, in his prototype for the world’s first telegraph receiver, he used a painter’s canvas stretcher as the frame. “So, in a way, he kind of pictured the technology,” said Staiti. Today, that prototype—now in the collection of the Smithsonian—reveals a marriage of innovation and artistry that elegantly summarizes the two halves of Morse’s influential career.

—Abigail Cain

No comments:

Post a Comment