https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-7-vanishing-technologies-making-a-comeback-through-art

7 Vanishing Technologies Making a Comeback through Art

An

increasing number of millennials have never used a landline, worn an

analog wristwatch, or mailed a handwritten letter. They’re also not

learning art and design technologies that previous generations took for

granted. Does that mean these tools are on the verge of extinction?

Fortunately, it isn’t that simple.

The scope of digital technology has made many things obsolete, from traditional black-and-white film to the homemade cassette mixtape, but it also prevents them from ever disappearing completely. Enthusiasts can congregate online, exploring, preserving, and sharing information on dwindling technologies before they’re ever truly lost. (Darkroom photography may be dying as a commercial trade, but it’s very much alive to artists and hobbyists across the internet.)

In the hands of artists and designers, a bygone technology can take on a new significance. “In the past, some of my students didn’t recognize a handmade garment as a ‘real’ garment because it didn’t look perfect the way clothes do in a store,” says artist and Parsons professor Pascale Gatzen. Now, perhaps in response to the homogeneity of mass-produced fashion, more students want to create by hand. “There is a strong desire to move beyond this generic reality and move towards a more intimate and experiential space,” Gatzen adds.

For the next generation of artists, there can be real value in resurfacing tools and techniques that may have been dropped from the art school curriculum. Here are six vanishing technologies to consider pursuing, and one that should potentially be avoided.

The scope of digital technology has made many things obsolete, from traditional black-and-white film to the homemade cassette mixtape, but it also prevents them from ever disappearing completely. Enthusiasts can congregate online, exploring, preserving, and sharing information on dwindling technologies before they’re ever truly lost. (Darkroom photography may be dying as a commercial trade, but it’s very much alive to artists and hobbyists across the internet.)

In the hands of artists and designers, a bygone technology can take on a new significance. “In the past, some of my students didn’t recognize a handmade garment as a ‘real’ garment because it didn’t look perfect the way clothes do in a store,” says artist and Parsons professor Pascale Gatzen. Now, perhaps in response to the homogeneity of mass-produced fashion, more students want to create by hand. “There is a strong desire to move beyond this generic reality and move towards a more intimate and experiential space,” Gatzen adds.

For the next generation of artists, there can be real value in resurfacing tools and techniques that may have been dropped from the art school curriculum. Here are six vanishing technologies to consider pursuing, and one that should potentially be avoided.

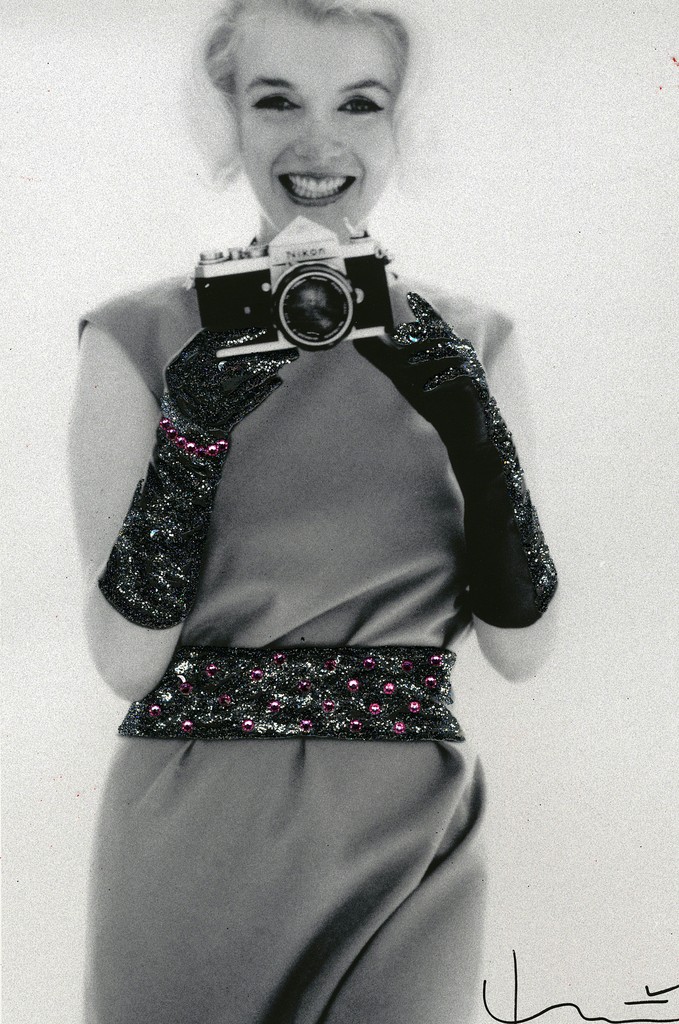

Film Photography

According to a 2015 article in TIME,

the volume of film produced for the U.S. market has decreased by 98% in

the past decade. For the average consumer, the convenience and economy

of digital photography put the nail in film’s coffin, and the popularity

of smartphones with high-resolution cameras buried it. However, analog

photography’s ability to capture detail, as well as its authenticity,

has kept it popular among dedicated amateurs and artists. (Take a spin

through the popular I Still Shoot Film photography blog, and you’ll see for yourself.) Young people represent film’s potentially fastest-growing market, with a recent survey showing that 30% of film users are reportedly under the age of 35.

Film offers structure (a limited number of exposures per roll), but

even still you don’t know exactly what you’re going to get out of any

given set of shots. Light leaks, optical distortion, unintentional

double exposures, chemical stains—there are endless possibilities for

happy accidents that often yield unexpected but desirable outcomes.

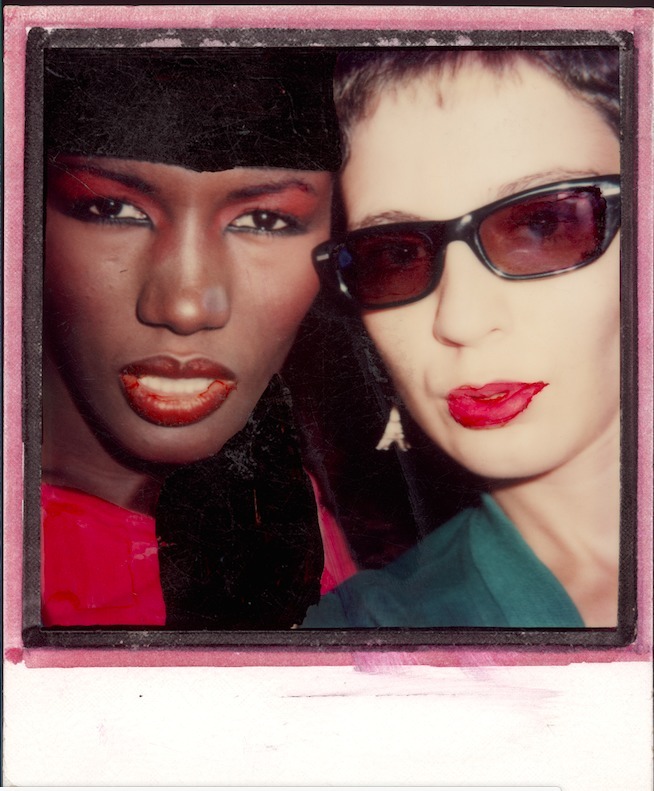

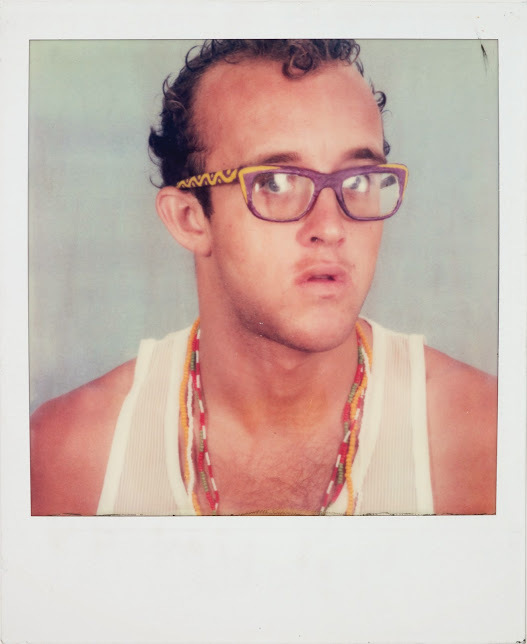

Polaroids

- Spring/Break: Benefit Auction 2016

Nothing balances nostalgia for the past with the fleeting present quite like a Polaroid picture. Beloved by artists from Keith Haring to Dash Snow,

the iconic instant film produced by Polaroid—the manufacturer of the

world’s first commercially viable instant cameras—has been in danger of

extinction since the corporation filed for bankruptcy in 2008 (its

second time in a decade). Fortunately, that’s when the Impossible

Project, the company that scooped up Polaroid’s old equipment and its

last remaining factory, stepped in, ultimately keeping the film alive by

re-engineering it from scratch. And while compact cameras yielding

credit-card sized photos (by the likes of Polaroid and Fujifilm) are

giving instant film a big comeback, the lesser-known, massive Polaroid

20x24 cameras, access to which was specifically granted to artists like Andy Warhol and Chuck Close,

are increasingly rare. In a case of fatal obsolescence, Elsa Dorfman, a

celebrated portraitist in her late seventies, may be forced to retire,

but not because she’s eager to stop working. The film required for the

20x24 camera she’s used for 30 years (Polaroid only manufactured a

handful of the cameras) is no longer being produced and will soon run

out.

Screen-Printed Textiles

Digital

fabric printing is offered in art schools and by companies like Print

All Over Me, a textile print-on-demand business based in New INC, the New Museum’s

cultural incubator. But while some commercial uses of silk-screen

printing have been displaced by digital (which is less technically

demanding but can be prohibitively expensive), silk-screen is more

omnipresent than ever before as a fine art medium. Much like analog

photography, printing by hand invites a more intimate experience with

the materials. Opportunities to try this technique abound, especially in

Brooklyn, where nearly every neighborhood seems to have its own print

shop. Shoestring Press in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, which gives its

members access to the materials for silk-screen printing, etching, and

lithography for a low monthly fee, also holds classes and runs an

exhibition space. Sofia Leiby,

an artist whose process integrates drawing, painting, and silk-screen

on canvas, uses screen-printing to create her vivid, gestural paintings.

A recent body of work sampled from a educational guidebook from the

early ’90s, reflecting on when type began to replace handwriting.

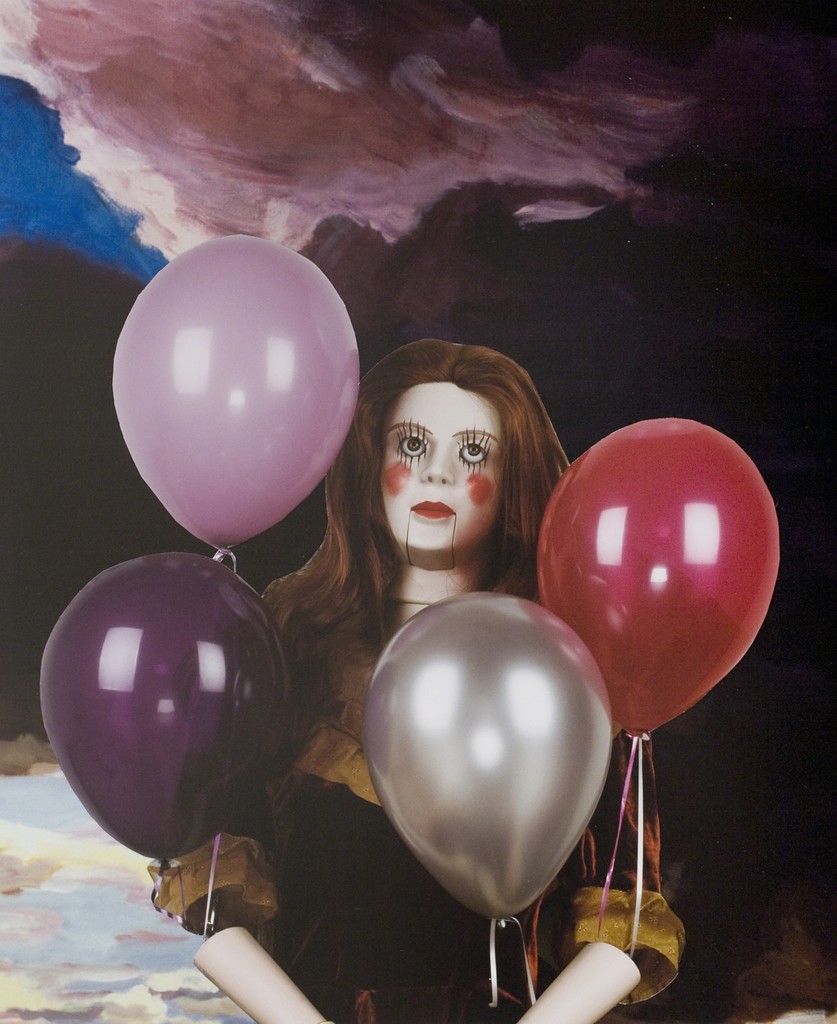

Practical Special Effects

Before the advent of computer-generated imagery (CGI), which really showed its teeth in Jurassic Park (1993)

when digital dinosaurs menaced the actors, movie effects were achieved

through elaborate makeup and intricate scale models. According to a recent story in Quartz,

the rise in digital technology has made things so bad for one practical

effects studio that they’ve turned to fields such as medical modeling

and government work. While old-school effects artists claim that models

are often cheaper than CGI, they have to be paid for up front, and

robotic models, unlike their CGI counterparts, can’t be updated

throughout production. As a result, budget-conscious studios often opt

for digital effects. Though you might think CGI would be embraced by

artists seeking cutting-edge tools, some prefer low-fi effects, while

others have budgets and limits on man-hours that do not match those of

major movie studios. (James Cameron’s 2009 3-D film Avatar, which

reportedly required 50–100 hours of production per frame, at 24 frames

per second, was budgeted at $237 million.) As such, practical effects

are alive and well in the art world, where artists as varied as the Quay

Brothers, Marnie Weber, and Julia Oldham use makeup, masks, and models to creepy, touching, and hilarious ends.

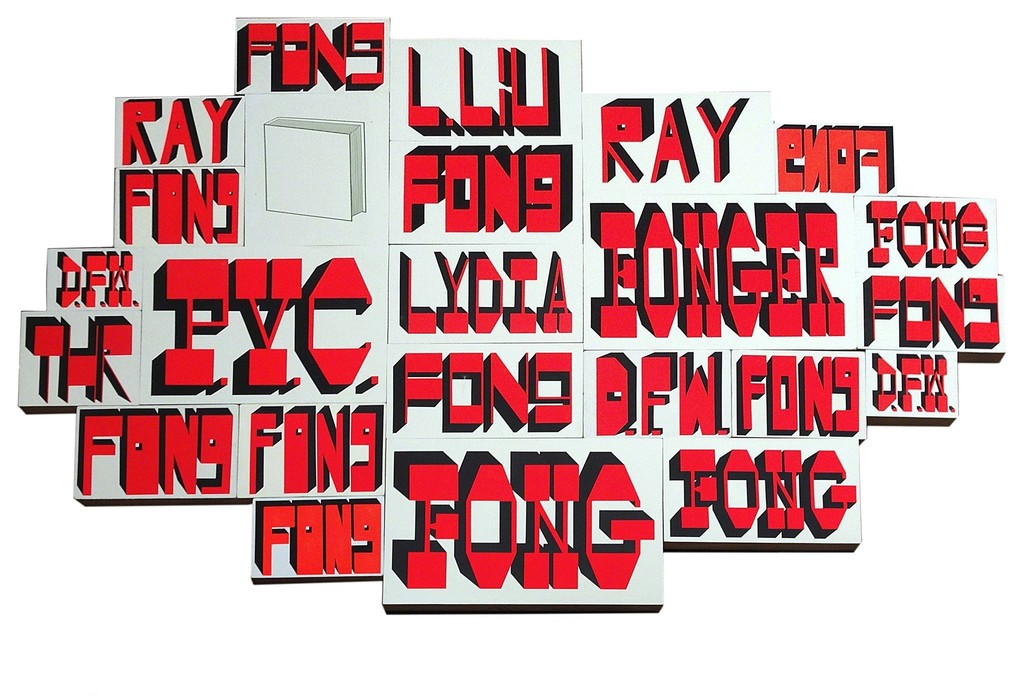

Sign Painting

Sign

painting is a skillset and profession that’s been quietly disappearing

from American life, replaced by cheaper, but less artful vinyl lettering

and digital printing. A recent documentary, Sign Painters (2013)

profiled several masters of the craft, whose work combines design,

illustration, painting, and calligraphy. As handmade signage disappears

from storefronts, hand lettering is making a comeback in the rest of the

design world in a big way, particularly in the work of the wildly

popular designer Jessica Hische. In recent years her hand-drawn letters

have graced everything from commemorative U.S. postage stamps to the

beautiful titles and credits of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom (2012).

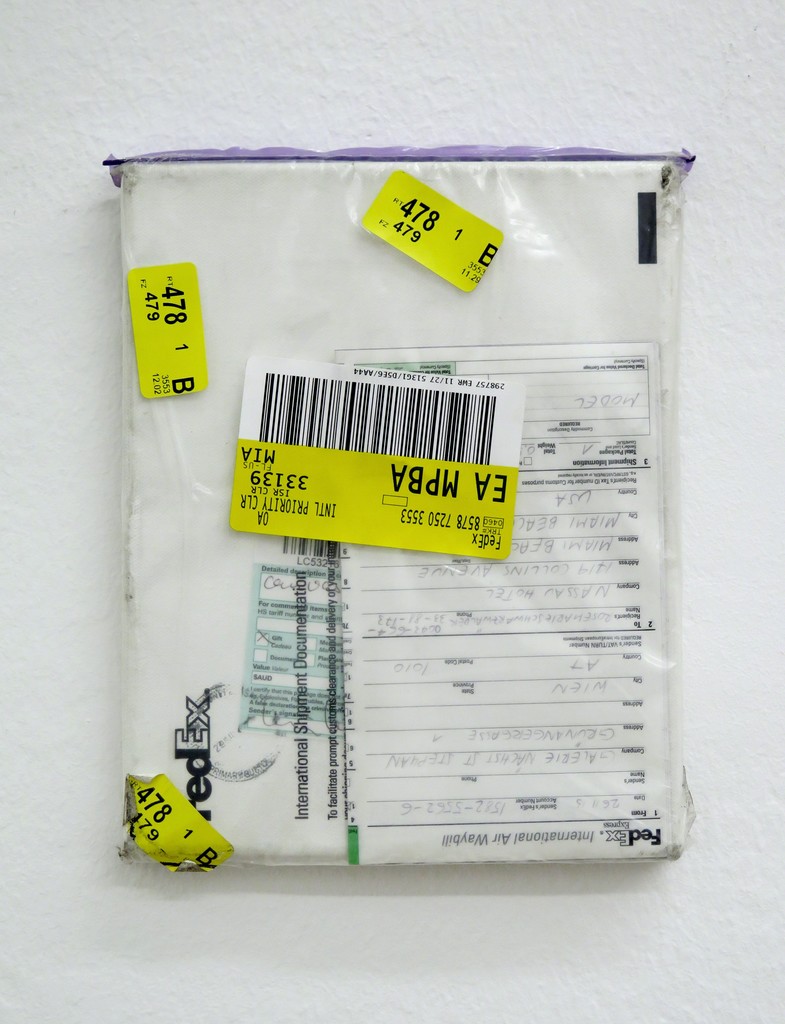

Mail Art

- Thomas Dane Gallery

To

say mail delivery is on the wane may be an understatement. From 2005 to

2015, the United States Postal Service has reduced its staff by more

than 200,000, and total volume of mail delivered has decreased by 26%. Mail art, on the other hand, is still holding on. The form was pioneered in the early 1960s by Pop artist Ray Johnson,

who mailed his friends drawing and collages, often with instructions

for making their own mark on the piece, such as “Please Add Hair to

Cher.” Johnson escaped the confines of the art market by using the

postal service, rather than a gallery, to disseminate his work. In 1983,

South American artist Eugenio Dittborn, during the dictatorship of

Augusto Pinochet in Chile, folded his trademark “Airmail Paintings” into

fractions of their size and mailed them out of the country, evading

government censorship. Many artists carry on this spirit, including David Horvitz, who makes mail art (and digital art) that circulates outside the commercial realm; Karin Sander, whose “Mailed Paintings” are unwrapped, ready-made blank canvases sent by post; and Walead Beshty,

whose “FedEx Sculptures” are the result of mailing shatterproof glass

boxes (which often crack en route) via the shipping service.

Cadmium Pigment

Cadmium

pigment is an old favorite that young artists may want to avoid. The

chemical element cadmium was discovered in early 19th century by a

German chemist, and by the mid-1840s it became a revolutionary asset for

artists’ paints—when they could afford it—beloved for its unmatched

fiery oranges, deep reds, brilliant yellows, and staying power. (Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and Munch’s The Scream would

not exist without it.) After animal testing found that the pigment is

potentially toxic if inhaled or swallowed, it narrowly escaped a

Europe-wide ban last year. Artists love it, however. And many fought

successfully to keep the pigment legal.

—Ariela Gittlen

—Ariela Gittlen

No comments:

Post a Comment