New Generation of Photographers Are Embracing Authenticity—and Finding It in Film

It’s

2007, four years after digital photography spiked to prominence,

eclipsing the sales of film. I’m working in the West Hollywood studio of

one of the world’s most famous photographers and the pioneer of digital

photography himself. Today, he’s tasked me with sifting through a

towering stack of hundreds of digital prints of a cloaked and

shaggy-haired Jesus, his palms outstretched to the heavens, to find the

perfect image of his hand. The chosen one would be stitched together by a

master digital retoucher—à la Frankenstein—to achieve the perfect man.

Nine years later, much of what was previously a highly technical process of retouching, an art form in itself, has been given to the masses. My parents’ laptops each have Photoshop. (They’re in medicine, and definitely not photographers.) Teenagers’ smartphones are armed with multiple editing apps. (Okay, mine is too.) With a few swipes of the finger, anyone can now more or less accomplish the result of the many nuanced retouching techniques that once turned even the experts cross-eyed.

But while this unlocked accessibility is thrilling in its ability to democratize artmaking, it also represents the current climax of this stage of what was once revolutionary technology. This has sparked a renaissance in analog photography, from fashion photographers embracing their genre’s roots to a new generation of fine art photographers who grew up with digital at their fingertips but are ditching it for a new outlet: film.

Nine years later, much of what was previously a highly technical process of retouching, an art form in itself, has been given to the masses. My parents’ laptops each have Photoshop. (They’re in medicine, and definitely not photographers.) Teenagers’ smartphones are armed with multiple editing apps. (Okay, mine is too.) With a few swipes of the finger, anyone can now more or less accomplish the result of the many nuanced retouching techniques that once turned even the experts cross-eyed.

But while this unlocked accessibility is thrilling in its ability to democratize artmaking, it also represents the current climax of this stage of what was once revolutionary technology. This has sparked a renaissance in analog photography, from fashion photographers embracing their genre’s roots to a new generation of fine art photographers who grew up with digital at their fingertips but are ditching it for a new outlet: film.

It’s

taken us four long decades to get here. From the young engineer Steven

Sasson’s invention of the digital camera at Eastman Kodak in 1975, to

the release of Photoshop in 1990, to each release of Apple’s iPhone with

a camera that trumps yet a greater number of DSLRs, digital technology

has tirelessly transformed an ever-evolving medium. But what happens

when these tools, once solely for the craftsmen, are so broadly

open-sourced?

The bar to take a decent photograph has been increasingly lowered, and the skills required to doctor it up wholly democratized. It’s no longer just fashion photographers synthesizing faces and liquefying limbs; amateurs are coolly retouching stray people out of their snaps or zapping their zits before publishing to Instagram. For hobbyists and pros alike, we’ve reached a point at which the photos we see are both indecipherable from reality and not representative of it. Trust suffers. Viewers and creators alike crave authenticity.

Manipulated photography existed long before Photoshop. Long before there were computers (never mind the infamous Skinnify app), Richard Avedon elongated models’ torsos and necks. He even physically cut-and-pasted heads and body parts. “The minute you pick up the camera you begin to lie—or to tell your own truth,” the late photographer once said.

A century before, Gustave Le Gray pieced together separate negatives for ocean and sky that, when combined, would print an otherwise unattainable seascape. And in the 1940s, British photographer Cecil Beaton trimmed the waistline and smoothed the wrinkles of then-Princess Elizabeth. This magic happened in the darkroom, where there are hard-stop limits to how far one can bend the truth.

The bar to take a decent photograph has been increasingly lowered, and the skills required to doctor it up wholly democratized. It’s no longer just fashion photographers synthesizing faces and liquefying limbs; amateurs are coolly retouching stray people out of their snaps or zapping their zits before publishing to Instagram. For hobbyists and pros alike, we’ve reached a point at which the photos we see are both indecipherable from reality and not representative of it. Trust suffers. Viewers and creators alike crave authenticity.

Manipulated photography existed long before Photoshop. Long before there were computers (never mind the infamous Skinnify app), Richard Avedon elongated models’ torsos and necks. He even physically cut-and-pasted heads and body parts. “The minute you pick up the camera you begin to lie—or to tell your own truth,” the late photographer once said.

A century before, Gustave Le Gray pieced together separate negatives for ocean and sky that, when combined, would print an otherwise unattainable seascape. And in the 1940s, British photographer Cecil Beaton trimmed the waistline and smoothed the wrinkles of then-Princess Elizabeth. This magic happened in the darkroom, where there are hard-stop limits to how far one can bend the truth.

Today,

digital technology has broadened the scope of what we can do—and who

can do it. But we’re hitting up against a wall where this manufactured

perfection mostly falls flat. This shift by no means isolates itself in

photography. In actuality, the shift reflects a broader societal move

that privileges realism and greater authenticity: Artists are turning to

handmade craft with pottery wheels and weaving looms; a tasting menu

served in the back room of a Bushwick pizza joint has replaced the

white-table-cloth opulence of Daniel; Facebook Live and Snapchat take

over the social media landscape.

It’s little surprise to see fashion photographers, grand masters of illusion, leading the charge back to good old, honest film. In May, Calvin Klein, never a stranger to provocation, unveiled a scandalous new ad campaign featuring an up-skirt shot of a 22-year-old Danish model. Perhaps even more radical, though, is that photographer Harley Weir shot the photos entirely on film. You might stop in your tracks for the hypersexual “I flash in #mycalvins” billboard, but this curiosity will be rewarded by the depth of color and dreamy, radiant light only photographs actually shot on film can provide. In a time when pre-packaged photo filters mean it’s never been easier to imitate the look of film, we’re aching for the real thing.

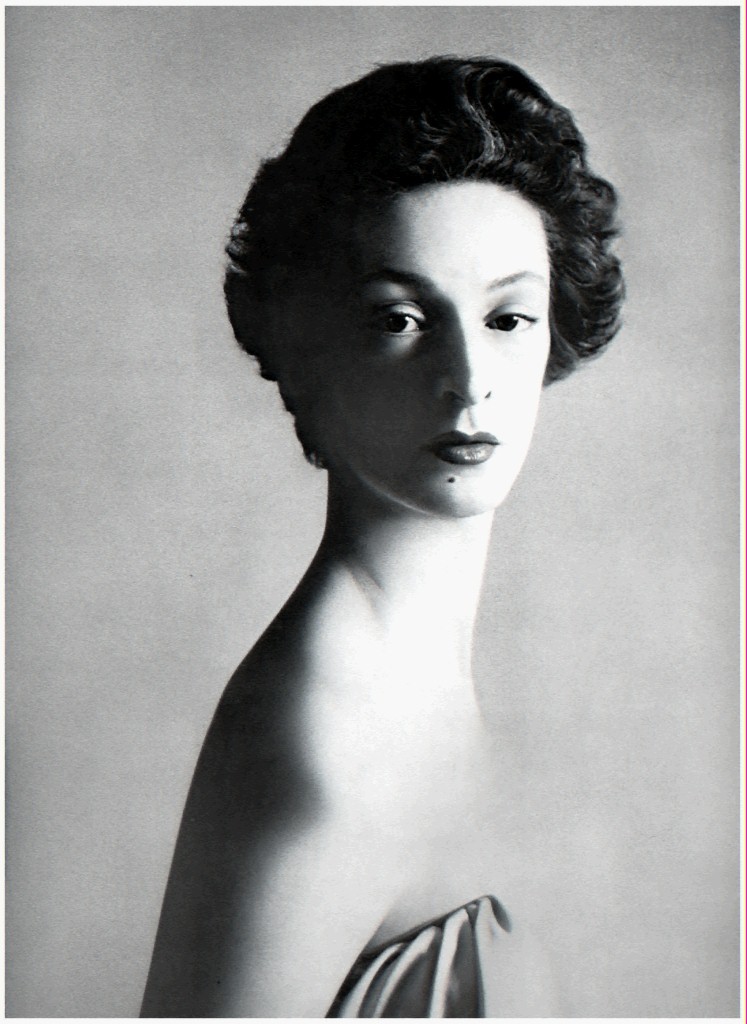

With the snap of her shutter Weir—a 27-year-old photographer who’s become one of fashion’s hottest young talents—channeled the very beginnings of fashion photography. Classic film cameras demanded immaculate styling and spot-on exposures but delivered, in exchange, luscious black-and-white prints. Rewinding a near half-century of innovation away from chemicals and film canisters, she caught an idling baton thrown by the pioneers of the 20th century, from Edward Steichen, who shot the first-ever fashion photographs of couturier Paul Poiret’s gowns, to Beaton and his beloved Rolleiflex.

It’s little surprise to see fashion photographers, grand masters of illusion, leading the charge back to good old, honest film. In May, Calvin Klein, never a stranger to provocation, unveiled a scandalous new ad campaign featuring an up-skirt shot of a 22-year-old Danish model. Perhaps even more radical, though, is that photographer Harley Weir shot the photos entirely on film. You might stop in your tracks for the hypersexual “I flash in #mycalvins” billboard, but this curiosity will be rewarded by the depth of color and dreamy, radiant light only photographs actually shot on film can provide. In a time when pre-packaged photo filters mean it’s never been easier to imitate the look of film, we’re aching for the real thing.

With the snap of her shutter Weir—a 27-year-old photographer who’s become one of fashion’s hottest young talents—channeled the very beginnings of fashion photography. Classic film cameras demanded immaculate styling and spot-on exposures but delivered, in exchange, luscious black-and-white prints. Rewinding a near half-century of innovation away from chemicals and film canisters, she caught an idling baton thrown by the pioneers of the 20th century, from Edward Steichen, who shot the first-ever fashion photographs of couturier Paul Poiret’s gowns, to Beaton and his beloved Rolleiflex.

And then there’re the fashion photographers who’ve stuck with film all along, like David Bailey,

who has captured some of the most iconic portraits of the last 60 years

with his own Rolleiflex camera. Does he care that photography has

opened up its flood gates to the masses? “No,” he said

in 2011, “it makes the good [photographs] even more powerful because it

hasn’t taken away the good ones. The good ones are still there. Digital

and Photoshop just moved mediocrity up a stop, that’s all. They’re

still mediocre—they just look better.”

Digital photographers continue to multiply. But, in step, a new generation of young photographers who’ve grown up with iPhones and touch-of-a-finger editing apps are side-stepping those technologies in favor of working with film. It’s slower, it’s harder to use—but that’s precisely what an emerging demographic, one met with constant virtual stimulation and flooded with digital images, is looking for.

Take 23-year-old rising star Petra Collins, for example, who shoots the beauty of teenage girlhood solely with 35mm film—and refuses to retouch—for its authenticity. (Her 2015 photo shoot pictured here captures girls crying, no airbrushing allowed.) According to a 2015 survey by Ilford Photo, 30% of all film users are under age 35. This means given the choice to shoot some 10,000 photos without changing a memory card and instant gratification, they’re opting for analog’s 24 images per roll of film in equal numbers to the other two thirds of the population. No longer starry-eyed for sharpness, they’re swapping pixels for grain, following a slowed-down path to imperfect but real and emotional pictures that, alongside technological innovations, are every bit as renegade as the digital prints once were.

Digital photographers continue to multiply. But, in step, a new generation of young photographers who’ve grown up with iPhones and touch-of-a-finger editing apps are side-stepping those technologies in favor of working with film. It’s slower, it’s harder to use—but that’s precisely what an emerging demographic, one met with constant virtual stimulation and flooded with digital images, is looking for.

Take 23-year-old rising star Petra Collins, for example, who shoots the beauty of teenage girlhood solely with 35mm film—and refuses to retouch—for its authenticity. (Her 2015 photo shoot pictured here captures girls crying, no airbrushing allowed.) According to a 2015 survey by Ilford Photo, 30% of all film users are under age 35. This means given the choice to shoot some 10,000 photos without changing a memory card and instant gratification, they’re opting for analog’s 24 images per roll of film in equal numbers to the other two thirds of the population. No longer starry-eyed for sharpness, they’re swapping pixels for grain, following a slowed-down path to imperfect but real and emotional pictures that, alongside technological innovations, are every bit as renegade as the digital prints once were.

Undoubtedly,

artists will continue to push forward what’s possible in the use of

digital technology to capture images. Tomorrow, even, an artist might

hack together a means of image capturing that completely blows apart our

understanding of how we can create and consume visual culture. I’ll be

the first one in line to take a look. But, if the above artists’ shifts

is any indication, the kind of digital photography we’ve come to know,

photography mediated through Photoshop, seems to have passed its climax

of relevance to those now entering the field.

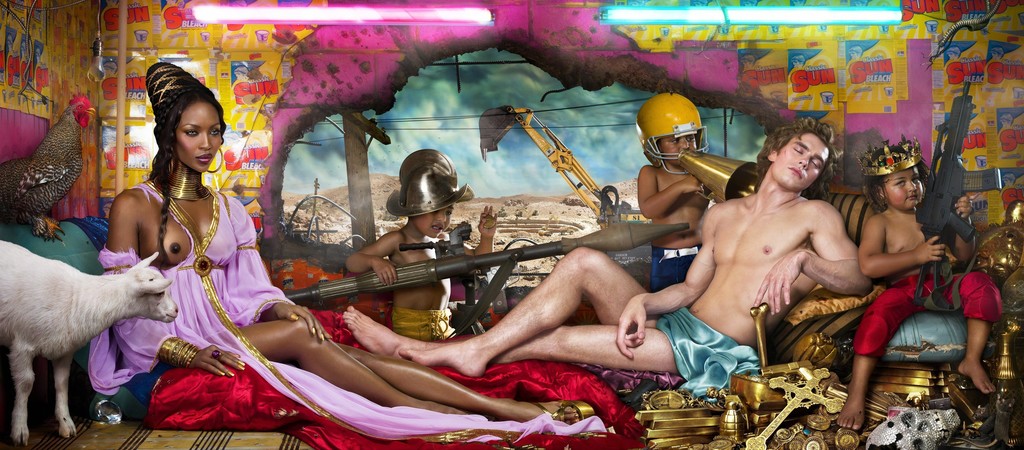

Will the masters of that medium who transformed the photograph from being a record of truth to a starting point for an artist’s imagination fall by the wayside in the process? Certainly not. They’ll continue to introduce us to surreal, composite worlds that defy everything we think we knew. But they’ll also be working all the harder to do so, fighting against a population edited to the point of becoming blasé.

—Molly Gottschalk

Will the masters of that medium who transformed the photograph from being a record of truth to a starting point for an artist’s imagination fall by the wayside in the process? Certainly not. They’ll continue to introduce us to surreal, composite worlds that defy everything we think we knew. But they’ll also be working all the harder to do so, fighting against a population edited to the point of becoming blasé.

—Molly Gottschalk

No comments:

Post a Comment