Betty Tompkins on Her “Fuck” Paintings, Art Talk, and Being Discovered by Jerry Saltz

When Betty Tompkins first

moved into Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood in the 1970s, it was a

rundown, high-crime district reeling from the city’s economic decline

and exodus of industrial manufacturing plants. “There was nobody else

living here,” Tompkins recalls, sitting in her studio loft in the same

neighborhood today, now across from the Apple store and overlooking the

throngs of tourists that beat a path through the shopping mecca day and

night. “The idea that regular people would want to take over these

disgusting spaces and build from scratch—that had not caught on.”

Before “gentrification” had entered the general lexicon, artists moved into the area to capitalize on cheap space, despite it being a less than hospitable environment, especially for women. “At the time, this was a factory neighborhood and we were a clear minority, so to walk on the streets in the daytime was an adventure in misogyny. There were probably artists on every block. We had a whistle system; if you were out at night and you were in trouble, you blew your whistle.”

Before “gentrification” had entered the general lexicon, artists moved into the area to capitalize on cheap space, despite it being a less than hospitable environment, especially for women. “At the time, this was a factory neighborhood and we were a clear minority, so to walk on the streets in the daytime was an adventure in misogyny. There were probably artists on every block. We had a whistle system; if you were out at night and you were in trouble, you blew your whistle.”

- Galerie Rodolphe Janssen

- Galerie Rodolphe Janssen

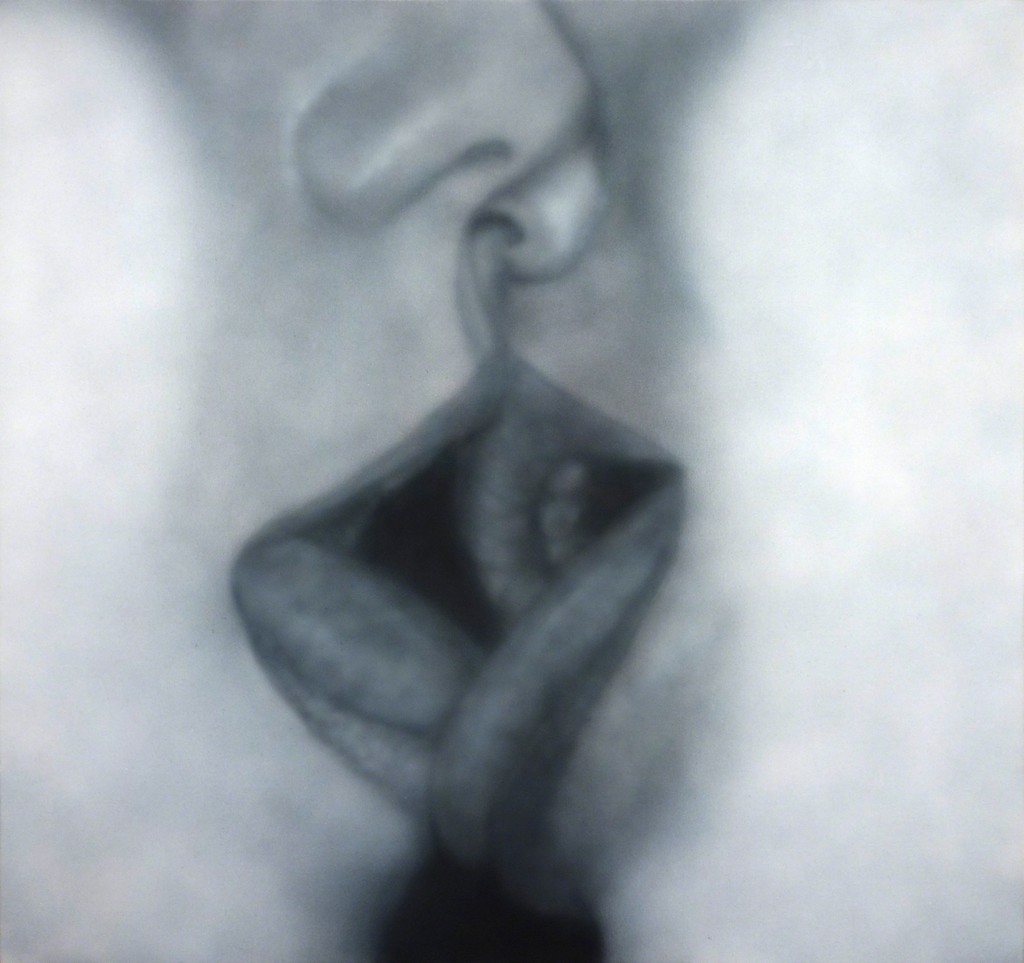

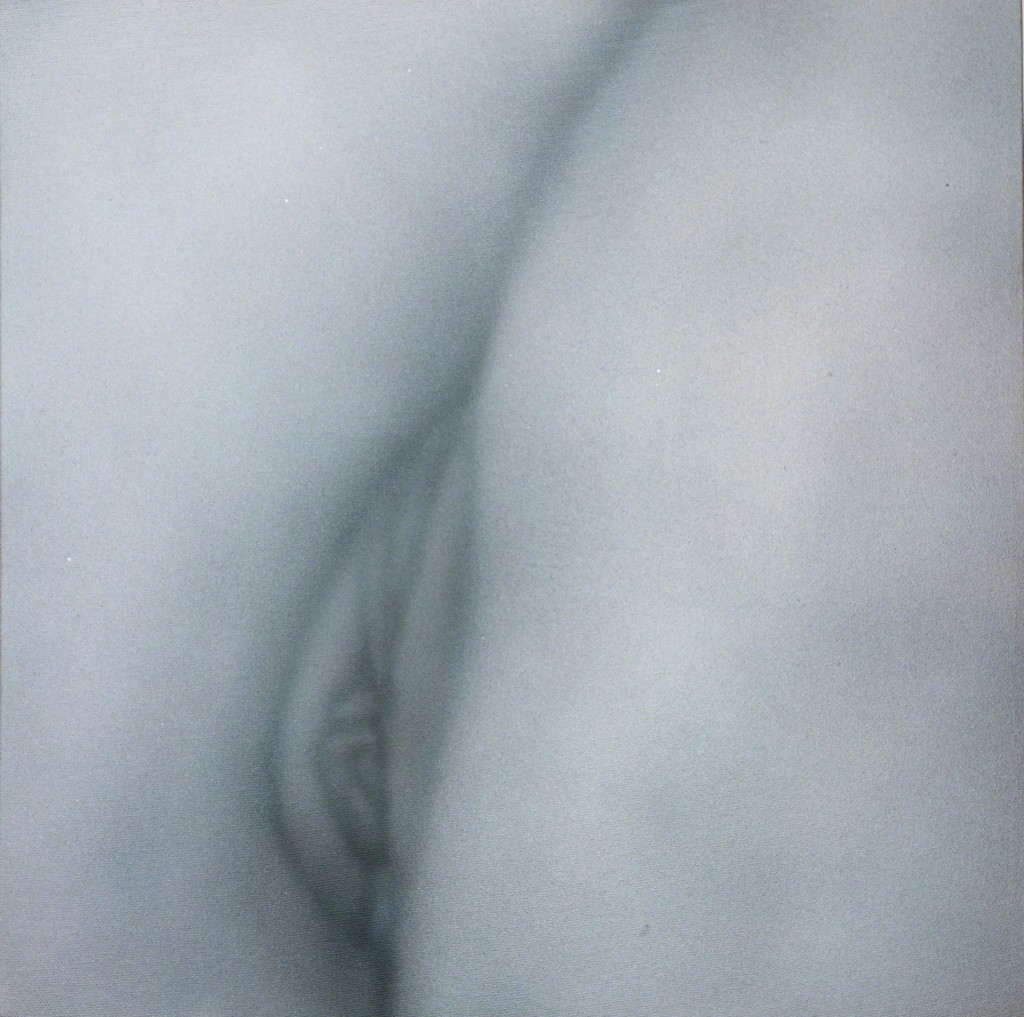

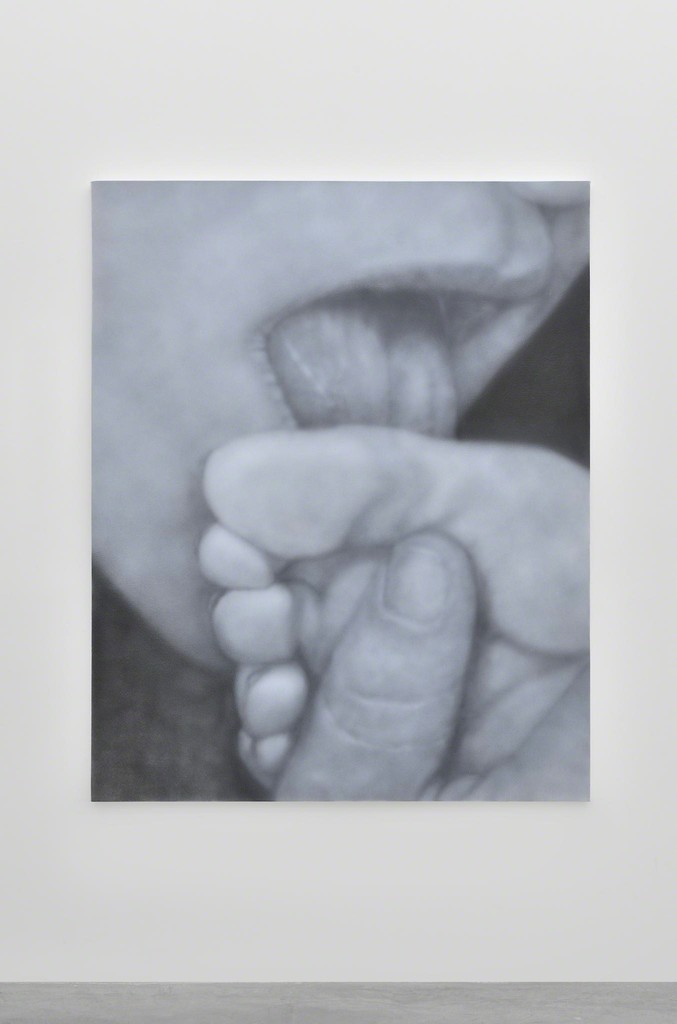

It

was back then that Tompkins, now 69 years old, composed the first of

the large-scale, soft-focus grisaille compositions of closely cropped

sexual scenes that she is known for. Among the canvases propped up

against the walls of her Prince Street studio on the day I visit is one

of an abstract dark mass framed by hands and an orifice, elements that

organize themselves in the mind’s eye to form a mouth covering an erect

penis. Nearby there are several others featuring curving, intersecting

lines that coalesce into images of female genitalia when viewed at a

distance—all with the hazy quality achieved with an airbrush. For

Tompkins, who is ebullient and excitable in person, dressed in black

sweats with a wild mop of curly hair, it’s this elastic quality that

interests her.

“If you walk up close,” she tells me, beckoning me to the painting’s surface, “this is the distance where painters normally paint. It’s an arm’s length away plus a couple of inches, but there’s nothing there. The image dissipates, you have no idea what you’re looking at. And as you step back, the image starts to cohere. It’s a different painting wherever you’re standing. I really love that.” This sense of dialogue with the paintings—of becoming absorbed in their soft forms before resolving them into discernible images that give “a subject matter kick,” as Tompkins describes it, is where their power resides.

“If you walk up close,” she tells me, beckoning me to the painting’s surface, “this is the distance where painters normally paint. It’s an arm’s length away plus a couple of inches, but there’s nothing there. The image dissipates, you have no idea what you’re looking at. And as you step back, the image starts to cohere. It’s a different painting wherever you’re standing. I really love that.” This sense of dialogue with the paintings—of becoming absorbed in their soft forms before resolving them into discernible images that give “a subject matter kick,” as Tompkins describes it, is where their power resides.

Yet

for some three decades the artist was largely overlooked. “I was going

around to all of these shows every month, and I found most of the shows

to be really boring,” Tompkins remembers of her early days in the New

York art world. “They were all by men, of course. Every dealer that I

spoke to said, ‘Come back in 10 years when you’ve found your voice,’

because that’s what they were used to—Hoffman and de Kooning, all these

Abstract Expressionist guys, they didn’t have their first shows until

they were somewhere in their 40s to 50s. Some of the dealers said, ‘And

don’t come back then either because we don’t show women.’ It was

actually very freeing to me. I had no expectations.”

In

an era when second-wave feminist artists were creating work

collectively, Tompkins set out on her own. “I had grown up on the

political left as a child,” she reflects. “My father was the head of the

Progressive Party in Philadelphia, which was very far-left. And I’d had

enough. I didn’t like how groups dealt with semantics and split hairs,

and would have huge fights instead of coming together... I saw that as a

big failing.” Did she consider herself a feminist, back then? “Oh, I

thought I was one, but I never went to the meetings. And according to

historical perspective, if you didn’t read the books and go to the

discussion groups and the meetings, you’re not actually considered a

feminist.”

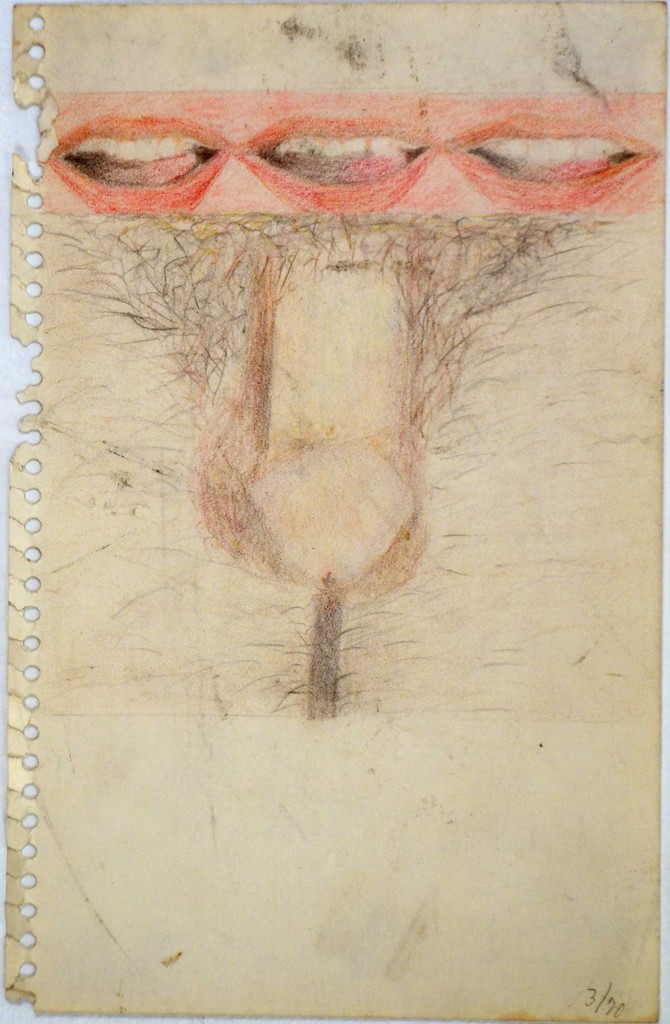

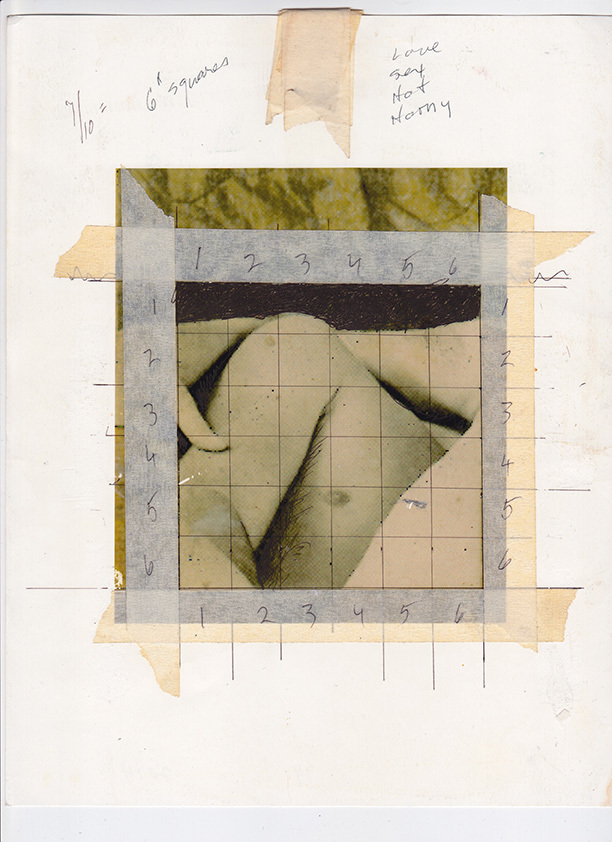

While

Tompkins’s work was no less subversive than that of her feminist

peers—her paintings of masturbation and penetration inverted the male

gaze and addressed taboo themes of female desire—she was driven not by

an agenda, but by passion and curiosity, unhindered by the expectations

of her sex. The subject matter for her “Fuck” paintings arose

intuitively, in response to the discovery of her first husband’s porn

images. “One day I’m looking at them, and I’m like, ‘You know, if you

take out all of this crap, you’ve got a really beautiful arrangement of

something.’” Porn, often of a vintage ilk, would continue to be her

source for the series.

Tompkins

speaks in equally frank and uncomplicated terms about the moment that

language entered her practice. “It was in the late 1970s, and conceptual

art was really very big. I got so disgusted with the articles about it,

because they were written in gobbledy-gook. You know, art talk. I would

get so pissed off, I would take my art magazines and throw them against

the wall!,” she says. “One day, I said: People want things to read?

Let’s write something. So I just started writing, ‘COW, COW, COW, COW.’”

This

led to her stamp paintings—images composed with manual word stamps,

applied serially to the canvas in various tonal shades—and, later, to

“Woman Words,” a project begun in 2002 and repeated in 2013, in which

Tompkins invited members of the public to send her verbal descriptors of

women. The response was staggering; she received 1,500 unique words and

phrases in seven languages to her first appeal alone. “The four most

often repeated words were the same in both groups: ‘bitch,’ ‘cunt,’

‘slut,’ and ‘mother,’” she says matter-of-factly, sliding open a drawer

and pulling out a small pile of scrapbook pages, torn from their

bindings, each painted in black and overlaid with short descriptions of

women in bold white text. These, along with two of her paintings, will

be on view next week at Art Brussels, where they’ll be paired with the work of the young French painter Lucas Jardin in

a special installation titled “A Sight for Sore Eyes”—the latest

edition of #ArtsyTakeover, a project in which artists collaborate with

Artsy to reimagine the art fair booth.

Fairgoers

may well be familiar with her work now, but recognition came late to

Tompkins. It wasn’t until 2003 that her remaining “Fuck” paintings were

uncovered from beneath the artist’s pool table, applied to stretchers,

and exhibited—thanks in large part to art critic Jerry Saltz. The story

goes something like this: It was the ’90s, and Tompkins heard through

the grapevine that Saltz was curating a show about sex; on a whim, she

sent him some of her slides. Resounding silence. A couple of years later

she got a call from New York dealer Mitchell Algus, after those same

slides turned up on his desk. Algus hosted a solo show of her work soon

after.

“I only did nine of the original paintings, “ she recalls, “and one got destroyed. It got a rip in it. I knew nothing about conserving paintings or getting them fixed—and I didn’t have any money anyway—so out in the trash it went. And then there were eight.” Two were sold early, one to Jack Klein, “one of the biggest landlords in SoHo,” she says, “who had amassed this incredible collection by being the landlord of people like Tom Wesselmann, and taking rent in trade.” Four were sold by Algus, and Tompkins kept two for herself.

“I only did nine of the original paintings, “ she recalls, “and one got destroyed. It got a rip in it. I knew nothing about conserving paintings or getting them fixed—and I didn’t have any money anyway—so out in the trash it went. And then there were eight.” Two were sold early, one to Jack Klein, “one of the biggest landlords in SoHo,” she says, “who had amassed this incredible collection by being the landlord of people like Tom Wesselmann, and taking rent in trade.” Four were sold by Algus, and Tompkins kept two for herself.

In

recent years, Tompkins has picked up her airbrush and returned to her

“Fuck” paintings once more, to considerable success—both with the old

guard, as seen in her 2012 exhibition with Brussels bastion Rodolphe Janssen,

and a younger New York crowd. This past winter saw her solo show at

Meatpacking gallery 55 Gansevoort, and in the coming months her works

will be included at NADA with LES gallery Louis B. James

and at the Bruce High Quality Foundation University’s new space this

fall. “It was like my hand knew what to do,” she remembers, “It

was going: At last! Welcome back! Ta-da!”

—Tess Thackara

Betty Tompkins’s work will be on view at the Artsy booth at Art Brussels from April 25th – 27th, 2015.

Explore Art Brussels on Artsy.

—Tess Thackara

Betty Tompkins’s work will be on view at the Artsy booth at Art Brussels from April 25th – 27th, 2015.

Explore Art Brussels on Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment