The Most Iconic Artists of the Baroque, from Caravaggio to Rembrandt

- Large Self-Portrait, 1652

- Bacchus, 1589Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Self-Portrait, ca. 1650

- Studio of Sir Peter Paul RubensPeter Paul Rubens, ca. 1620

Named after the French word denoting extravagance and ornate detail, the Baroque was the dominant trend of European art from the 17th century to the middle of the 18th. Literally referring to an irregularly shaped pearl, it was less a principled stylistic movement than a suite of reactions to and rebellions against the restrained proportions of Renaissance classicism and the vagaries of Mannerism. It was a time of invention and liberation in artistic expression, but also one in which art served religious and political ends.

Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel manifested the theme of variation in Baroque music, while the monumental Palace of Versailles and spectacular, undulating buildings designed by Christopher Wren, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, and Francesco Borromini exemplify architecture of the period. Gian Lorenzo Bernini transformed the practice of sculpture, showing in works like the Fountain of the Four Rivers (1648-51) and the Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1647–52) unprecedented levels of detail and delicacy. Occurring between the ages of Enlightenment and Absolutism, Baroque style was encouraged as a powerful device for the Counter-Reformation, contributing to the reassertion of the Catholic Church through art.

Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel manifested the theme of variation in Baroque music, while the monumental Palace of Versailles and spectacular, undulating buildings designed by Christopher Wren, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, and Francesco Borromini exemplify architecture of the period. Gian Lorenzo Bernini transformed the practice of sculpture, showing in works like the Fountain of the Four Rivers (1648-51) and the Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1647–52) unprecedented levels of detail and delicacy. Occurring between the ages of Enlightenment and Absolutism, Baroque style was encouraged as a powerful device for the Counter-Reformation, contributing to the reassertion of the Catholic Church through art.

- Palais de Versailles, 1668-1685

- Fountain of the Four Rivers, the Ganges (Asia), 1648-1651

___

Italy

Annibale Carracci

This was especially true in the case of Italian painting. Rome’s Farnese Palace was the canvas for Annibale Carracci’s Loves of the Gods (1597–1601), a cycle of frescos commissioned by a cardinal that demonstrated early signs of Baroque innovations. Part of an academically trained, artistic family, Carracci certainly drew inspiration from classical architecture and sculpture on display throughout the city. But his idea to create an impossible world—one in which mythological scenes in false frames are supported by angelic putti, and surrounded by illusionistic architectural features and painted skies—was a radical departure from conventional design.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

- The Calling of St Matthew, 1599-1600

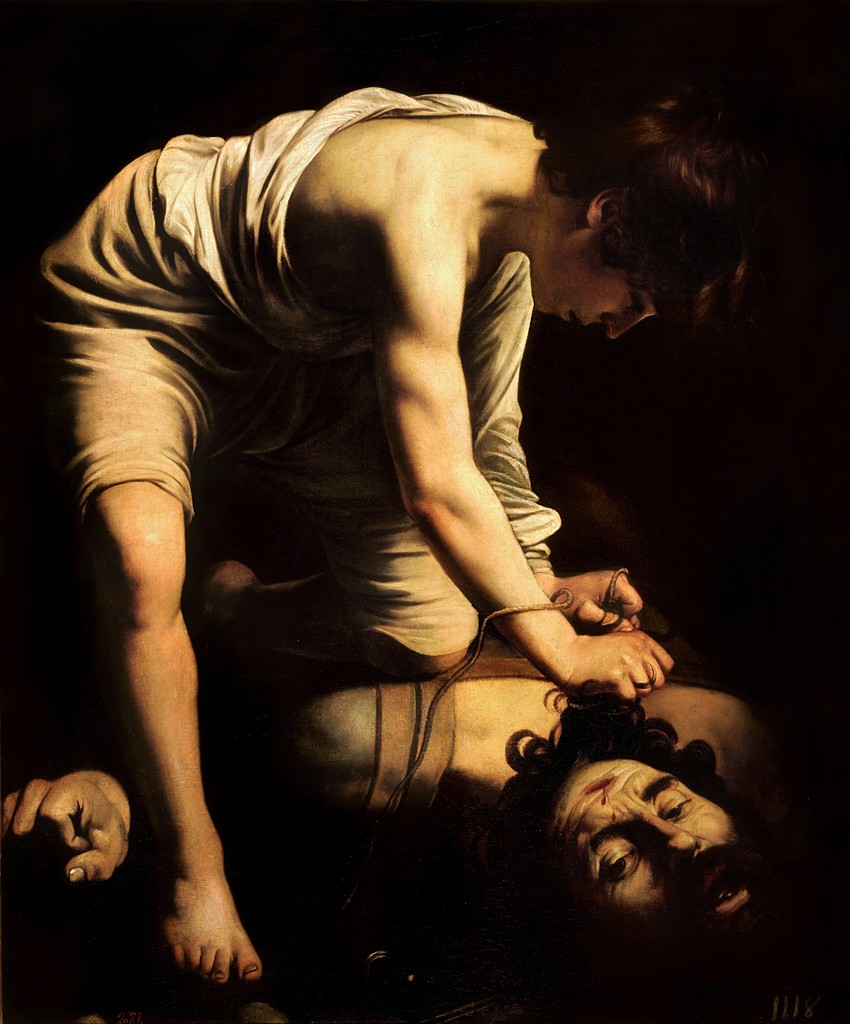

- David victorious over Goliath, 1600

While Carracci also developed an idea of landscape that would be associated with French and Northern styles, the work of other Italian artists sent shockwaves throughout Europe. None was more influential than Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. A brash, dangerous personality, Caravaggio brought gritty realism to his canvases. He painted peasants and prostitutes from the street, right down to the dirt under their fingernails, as in Boy Bitten by a Lizard (1595–1600), and cast himself as a jaundiced Bacchus and the slain giant Goliath. But however shocking works like his famous Medusa (1595–1598)—with its bloody depiction of a beheading—were, his pervasive style of chiaroscuro (the juxtaposition of light and dark to create extreme contrast) was a decisive breakthrough. By highlighting the most dramatic moment of a religious scene, works like The Supper at Emmaus (1605-06) depict profound spiritual revelations, symbolized by the intervention of divine light into an everyday setting.

Artemisia Gentileschi

- Judith and Holofernes, ca. 1620Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Mary Magdalen with the Smoking Flame, ca. 1640

While many Italian painters would follow this compositional mode, with brightly lit scenes emerging from dark backgrounds, Artemisia Gentileschi was one of the rare women who emerged from the shadows of the male-dominated history of art. Her Judith and Holofernes (1620) is iconic and demonstrative of her work; not only does it portray a biblical episode of female strength and agency, it also offers a shining example of tenebrism, the caravaggesque style in which light comes from a single, often oblique source, creating dramatic shadows.

_________________

France, Spain, & Netherlands

- Aristotle, 1637

- San Francisco en meditación (Saint Francis in Meditation), 1639

Tenebrism’s dramatic punch made it extremely popular, winning acolytes across Europe. In France, Georges de la Tour produced some of the best-known works in the style, while adding to it original motifs. St. Joseph the Carpenter (1642) displays his signature device of light emanating from a candle, illuminating biblical scenes played out by people in intimate interiors. A Spanish artist working in Naples, José de Ribera further intensified contrast in works like Aristotle (1637), while his countryman Francisco de Zurbarán cast many of works, from religious scenes like Saint Francis in Meditation (1635-39) to still-life paintings, in a tenebrist mode.

Diego Velázquez

- Las Meninas (The Maids of Honour), 1656

- The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus'), 1647-1651

While the tranquil, sentimental work of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo became highly esteemed across Europe, the preeminent Spanish painter of the age, and one of the most revered artists in history, was Diego Velázquez. With rigorous academic training, high ambitions, and a precocious talent, he rose to the rank of official painter to Philip IV, King of Spain, whose patronage of Velázquez and other artists was a hallmark of the period. Adept in many different kinds of painting, from still-lifes to portraits to religious paintings, Velázquez also possessed a rare ingenuity that allowed him to fold several of these genres deftly into each other, as in The Waterseller of Seville (1618-22).

While many may recognize his famous Rokeby Venus (1647-51) (and perhaps its infamous chapter in the history of iconoclasm), Velázquez’s greatest achievement was Las Meninas (1656), an inventive group portrait of the royal family of Spain. Philip IV and his wife Mary Anne appear in it, but are placed in the position of the viewer and can be seen only dimly reflected in the mirror hung on the back wall of a room. Below the reflection of her parents stands the petite princess Margarita (la Infanta) surrounded by her handmaidens (las Meninas). To the left is a self-portrait of Velázquez, shown in the act of painting, it seems, the very image we now observe. A virtuosic weave of artist, subject, reflections, and angles, the painting has, since its creation, inspired responses from critics, scholars, poets, playwrights, and philosophers.

While many may recognize his famous Rokeby Venus (1647-51) (and perhaps its infamous chapter in the history of iconoclasm), Velázquez’s greatest achievement was Las Meninas (1656), an inventive group portrait of the royal family of Spain. Philip IV and his wife Mary Anne appear in it, but are placed in the position of the viewer and can be seen only dimly reflected in the mirror hung on the back wall of a room. Below the reflection of her parents stands the petite princess Margarita (la Infanta) surrounded by her handmaidens (las Meninas). To the left is a self-portrait of Velázquez, shown in the act of painting, it seems, the very image we now observe. A virtuosic weave of artist, subject, reflections, and angles, the painting has, since its creation, inspired responses from critics, scholars, poets, playwrights, and philosophers.

Peter Paul Rubens

- Tiger, Lion and Leopard Hunt, 1616

- Le debarquement de Marie de Médicis au port de Marseille le 3 November 1600 (Maria Medici arrives in Marseille, Nov. 3 1600), ca. 1622-1625

Velázquez was himself deeply inspired by Peter Paul Rubens, one of the greatest Flemish artists of the period and an accomplished diplomat. As prolific as he was urbane, Rubens had deeply impressed both Velázquez and King Philip on a visit to the latter’s court in Madrid. While heavily influenced by the Italian tradition, Rubens became especially known for his representations of fleshy, full-bodied women, often with allegorical meanings. An immense cycle of 24 paintings for Marie de Médici epitomizes this style, where expressive nudes help to dramatize the overarching political narrative depicting the Queen of France’s life.

Nicolas Poussin

Rubens’s style was so prominent that it became one of two poles in an international artistic debate during the period. Where Rubenistes prioritized color, Poussinistes followed the example of the French artist Nicolas Poussin, who stressed the importance of drawing. Academically trained in France and Italy, Poussin was committed to reinstating classical principles: precise draughtsmanship, compositional balance, and the saga of human emotions, often expressed through tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The Rape of the Sabine Women (1637–38), a scene from Plutarch’s history of ancient Rome, is a famous example of Poussin’s capacity to distill narrative into strained, sinuous poses and pained facial expressions.

- Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648

- The Rape of the Sabine Women, 1637-1638Musée du Louvre, Paris

Claude Gellée

While Poussin also brought this emotional emphasis to landscape painting, as in the Burial of Phocion (1648-49), the most important landscape painter of the period was Claude Gellée, called Claude Lorrain or simply Claude. Born in France, Claude developed his mature style in Italy. The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba (1648), which creates perspectival depth through classical architecture and natural light emanating from the sun, typifies Claude’s invention of the idealized harbor scene. Pastoral scenes like Landscape with Nymph and Satyr Dancing (1641) represent the idealized land, full of mythological beings and framed by repoussoir trees and classical ruins.

Rembrandt van Rijn

- The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch (The Night Watch), 1642

Claude’s techniques were instructive for generations of subsequent landscape artists, including Jacob van Ruisdael, one of the great painters in Holland. Rather than employing religious themes to reveal spiritual and artistic truths, as with Italian Baroque art, Dutch artists from the period looked to nature. Their collective ethos might be summarized by the guiding principle of Rembrandt van Rijn, one of the greatest artists of the Baroque, or any period: one should be guided by nature only. His iconic The Night Watch (1642) represents one of the great climaxes of naturalism in Western art. But while they may fall within the broad and varied parameters of Baroque art, Rembrandt, Ruisdael, Rubens, and other Dutch artists like Frans Hals, Anthony van Dyck, and Johannes Vermeer worked within a more specific context: Holland’s Golden Age, a period with its own complex history.

—George Philip LeBourdais

Explore iconic artists and artworks from the Baroque on Artsy.

—George Philip LeBourdais

Explore iconic artists and artworks from the Baroque on Artsy.

No comments:

Post a Comment